Breast Cancer Part I: Incidence and Risk

Women

with

Disabilities

educational programs

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of

Breast Cancer in

Women with Disabilities

Part 1: Incidence and Risk

Women with Disabilities Education Project

Overview

Part 1:

Incidence and Risk

Part 2:

Screening and Diagnosis

Part 3:

Treatment, Rehabilitation, and Ongoing Care

www.womenwithdisabilities.org

Incidence

Breast Cancer in the United States:

Incidence

182,000 new cases diagnosed annually 1

One-third of all new cancers diagnosed in American women 2

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Reference Information. Revised: September 13, 2007.

2. Ahmedin J, et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66.

Breast Cancer in the United States:

Mortality

24% since 1990 1

Claims

40,000 women’s lives annually

Second-leading cause of cancer-related death in

American women 2

1. Ismail J, et al. J of Clin Oncology . 2007;25:TK-TK.

2. American Cancer Society. Cancer Reference Information. Revised: September 13, 2007.

Women with disabilities have the same risk of breast cancer as women without disabilities

.

1

in

8

lifetime risk

1

1. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2007-2008.

Women with disabilities are one-third more likely to die from their breast cancer than women without disabilities

1

1. McCarthy EP, et al. Ann Intern Med . 2006;145:637-645.

Why the Disparity?

After surgery for breast cancer, women with disabilities are less likely to receive: 1

– Radiotherapy

– Axillary lymph node dissection

They are also less likely to receive:

– Screening mammograms 2

Does lack of exercise play a role?

1. McCarthy EP, et al. Ann Intern Med.

2006;145:637-645.

2. Iezzoni LI, et al. Am J of Public Health . 2000;90:955-961.

Coming to Terms

What does disability mean?

Americans with Disabilities Act

A Person Has a Disability if He or She:

Has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual;

Has a record of such an impairment; or

Is regarded as having such an impairment 1

1. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

U.S. Surgeon General’s “Call to Action to

Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities”

Disabilities Are…

“…characteristics of the body, mind, or senses that, to a greater or lesser extent, affect a person’s ability to engage independently in some or all aspects of day-today life.”

Disabilities Are Not Illnesses.

“Just as health and illness exist along a continuum, so, too, does disability. Just as the same illnesses can vary in intensity from person to person, so, too, can the same condition lead to greater or lesser limitation in activity from one person to another.”1

1. Office of the Surgeon General. Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities . 2005.

Disability Models

Medical Model

Individual problem

Directly caused by disease

Social Model

Does not reside in individual

Created by environmental barriers

Words Matter

Handicapped

Disabled

Crippled

Defective

The Importance of Language

Avoid

The handicapped

Mentally ill person

Stroke victim

Person confined to a wheelchair; wheelchairbound

Able bodied

Use Instead

People with (who have) disabilities

Person with a mental illness

Person who had a stroke

Person who uses a wheelchair

Nondisabled

Risk Factors

Relative Risk Factors for

Breast Cancer

Increasing age

Family history of breast cancer in first-degree relative

BRCA gene mutations

Early menarche, late menopause

Nulliparity or > 35 years old at birth of first child

No history of breast-feeding

Personal history of breast cancer or certain noncancerous breast diseases/conditions, including higher breast density

Being overweight

Not getting regular exercise

Long-term use of hormone replacement therapy

Use of oral contraceptives

Alcohol consumption (more than one drink a day)

Treatment-dose radiation to the breast/chest

Factors That Put Women at High Risk

A BRCA gene mutation

A very strong family history of breast cancer, such as a mother or sister who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 or younger

A personal history of breast cancer, LCIS, or atypical hyperplasia

Past exposure to treatment-dose ionizing radiation during childhood or young adulthood

Risk-Reduction Strategies for

Women with Disabilities

All women should have a breast cancer risk assessment and be offered appropriate risk-management strategies

Identifying High-Risk Women

Encourages Women to:

Have more rigorous screening

Be counseled about preventive therapies

Assessment Tools:

Epidemiologic risk-assessment models (e.g., Gail model)

Genetic testing

The Modified Gail Model

Risk Factors Used In Calculation: 1

Current age

Age at menarche

Age at first live birth or nulliparity

Number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer

Number of previous benign breast biopsies

Atypical hyperplasia in a previous breast biopsy

Race

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Risk factors used in the modified Gail Model; 2007.

The Modified Gail Model

5-year Gail risk < 1.66% = low risk

5-year Gail risk > 1.66% = high risk

NCI’s Breast Cancer Risk

Assessment Tool: www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool

Genetic Testing

May predict risk more accurately than family history alone 1

5% –10% of women who develop breast cancer have BRCA gene mutations 1

Women with BRCA mutations have lifetime risk of 1

– Up to 85% for breast cancer

– Up to 60% for ovarian cancer

BRCA carriers at highest risk have family history of 2

– Breast cancer diagnosis ≤ age 35

– Contralateral breast cancer

1.

2.

Myers MF, et al. Genetics in Medicine . 2006;8:361-370.

Begg CB, et al. JAMA.

2008;299:194-201.

Clinical Options for Managing

Women at High Risk

Increased surveillance

– Clinical breast exam

– Mammography

– MRI

Chemoprevention

– Tamoxifen

– Raloxifene

Prophylactic surgery

Tamoxifen and Raloxifene: Assessing

Risks for Women with Disabilities

Increased risk of stroke and thromoboembolic events

(women with limited mobility already at risk) 1

Increased risk of uterine cancer 1

Other risks: 2

– Cataracts and other eye problems

– Bladder problems

– Vaginal problems

1. Vogel VG, et al., for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). JAMA.

2006;295:2727-2741.

2. National Cancer Institute. Reviewed May 13, 2002. Available at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Therapy/tamoxifen.

Managing Women with Disabilities on Tamoxifen and Raloxifene

Assess patient’s individual risk for thromoboembolism

Advise and assist patient with:

– Quitting smoking

– Lowering blood pressure

– Maintaining a healthy weight

– Exercising regularly

Follow patient closely

Prophylactic Breast Surgery: Assessing

Risks for Women with Disabilities

Reduces breast cancer risk by 90% in high-risk women 1

Most high-risk women report satisfaction with decision to have the surgery 2

Patient satisfaction is more variable regarding cosmetic results and body image 2

Special concern for women with disabilities:

How will the surgery affect my mobility and quality of life?

1. Hartmann L, et al. N Engl J Med . 1999;340:77-84.

2. Lostumbo L, et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2004;4:CD002748.

Managing Women with Disabilities

Who Chose Prophylactic Surgery

Discuss with patient how surgery will affect her adaptive and assistive needs

Make sure patient has sufficient home care after surgery

Start physical therapy before surgery

Postsurgical physical therapy essential for restoring function and quality of life

Modifiable Risk Factors

Being overweight

– Women overweight at age 50:

50% increase in risk 1

Not getting enough exercise

– 1.25–2.5 hours of brisk walking:

18% decrease in risk 2

Consuming alcohol daily

– Each 10 g of daily alcohol: 7.2% increase in risk 3

1. Ahn J, et al. Arch Intern Med . 2007;167:2091-2102.

2. McTiernan A, et al. JAMA . 2003;290:1331-1336.

3.Chen WY, et al. Ann Intern Med . 2002;137:798-804.

Women with disabilities often have more difficulty altering modifiable risk factors

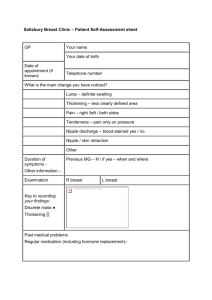

Distribution of Barriers to Improving

Eating Habits (n=359)

*

Barriers

Too tired to cook

Organic foods/health foods too expensive

Nutritious foods too expensive

Lack of desire or will power

Government disability pension is not enough

Too hard to go shopping

Not enough attendant time to shop/prepare food

Local food stores too expensive

Too busy

Difficulty chewing and swallowing fruit and vegetables

Not enough assistance with shopping

Local food stores not physically accessible

Food bank does not provide adequate source for food

Nutritional information not available in alternate formats

Attendant does not have enough time to help with feeding

Other

Frequency

61

49

39

90

76

69

62

194

125

124

113

110

34

21

3

47

Percentage

25.1

21.2

19.2

17.3

17.0

13.6

10.8

54.6

34.8

34.5

31.5

30.6

9.5

5.8

0.8

13.1

* Participants were able to cite more than one barrier.

Source: Hall L, Colantonio A, and Yoshida K. Int J of Rehabilitation Research . 2003;26:245-247.

Barriers to Increasing

Physical Activities

Lack of transportation

Lack of money

Lack of time

Inaccessible fitness centers

Healthcare and fitness professionals who are inexperienced with working with people with disabilities

Lack of social support

Fatigue and pain

Barriers to Increasing

Physical Activities

Lack of self-knowledge about capabilities for exercise and/or skills needed to engage in physical activity

Equip your facility with a weight scale that accommodates wheelchairs

Refer patients with disabilities to a dietician with experience addressing their unique dietary and exercise issues

National Center on

Physical Activity and

Disability (NCPAD)

www.ncpad.org

Alcohol Use Among Women with Disabilities

Alcohol use is as prevalent among women with disabilities as among the general female population 1

Discuss alcohol use and its breast cancer risk with all patients

Patients at high risk of breast cancer must carefully weigh risks and benefits of moderate alcohol use

1. Li L, Ford JA. Applied Behavioral Sci Rev.

1996;4:99-109.

Summary

Women with disabilities have same breast cancer risk as other women, but are one-third more likely to die from the disease

Reasons for this disparity in survival are unknown, but women with disabilities are less likely to undergo standard chemo and/or radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery and are less likely to have regular screening mammograms

All women with disabilities should be assessed for their breast cancer risk and offered risk-reduction strategies

Risk-reduction strategies raise special issues for women with disabilities that need a thorough clinician-patient discussion

Helping women with disabilities alter modifiable risk factors and adopt a more healthful lifestyle may require special tools and strategies

Resources

Breast Health Access for Women with Disabilities (BHAWD)

Call: 512-204-4866

TDD: 510-204-4574 www.bhawd.org

Center for Research on Women with Disabilities (CROWD)

Baylor College of Medicine

Call: 800-442-7693 www.bcm.edu/crowd

Health Promotion for Women with Disabilities

Villanova University College of Nursing

Call: 610-519-6828 www.nursing.villanova.edu/womenwithdisabilities

Magee-

Women’s Foundation

“Strength & Courage Exercise DVD” (a compilation of exercises helpful to breast cancer patients) http://foundation.mwrif.org/

National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Call: 1-800-CDC-INFO

TTY: 1-888-232-6348 www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp

National Center of Physical Activity and Disability

Call: 1-800-900-8086

TTY: 1-800-900-8086 www.ncpad.org

The National Women’s Health Information Center

Call: 1-800-994-9662

TDD: 1-888-220-5446 www.4women.gov/wwd

Susan G. Komen for the Cure www.komen.org

Women with Disabilities

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/women

References

Ahmedin J, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, and Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin.

2007;57:43-66.

Ahn J, Schatzkin A, Lacey JV, et al. Adiposity, adult weight change, and postmenopausal breast cancer risk.

Arch Intern Med.

2007;167:2091-2102.

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society issues recommendation on MRI for breast cancer screening. March 28, 2007. Available online.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2007-2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.;

2007.

American Cancer Society. Detailed guide: breast cancer: what are the key statistics for breast cancer? Cancer

Reference Information. Revised: September 13, 2007.

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Public Law 101-336. U.S. Statutes at Large 104 (1990), codified at

U.S. Code 42, §12101. Available at www.ada.gov/pubs/ada.htm#Anchor-Sec-47857 .

Becker L, Taves, D, McCurdy L, et al. Stereotactic core biopsy of breast microcalcifications: comparison of film versus digital mammography, both using an add-on unit. AJR.

2001;177:1451-1457.

Begg CB, Haile RW, Borg A, et al. Variation of breast cancer risk among BRCA 1/2 carriers. JAMA.

2008;299:194-201.

Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Eng J Med.

2005;353:1784-1792.

Breast Health Access for Women with Disabilities (BHAWD). Breast health and beyond: a provider’s guide to the examination and screening of women with disabilities, 2nd ed. January 2008.

Caban ME, Nosek MA, Graves D, Esteva FJ,McNeese M. Breast carcinoma treatment received by women with disabilities compared with women without disabilities. Cancer . 2002;94:1391-1396.

Chen WY, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormones, alcohol, and risk for invasive breast cancer. Ann Intern Med.

2002;137:798-804.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer —collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and

95,067 women without the disease. Brit J of Cancer.

2002;87:1234-1245.

CROWD, Baylor College of Medicine. Health behaviors —weight management; 2007. Available at www.bcm.edu/crowd/?pmid=1430 .

Elmore JG, Fletcher SW. The risk of cancer risk prediction: “what is my risk of getting breast cancer?” J of the

NCI.

2006;98:1673-1675.

Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. JAMA.

2006;296:185-192.

Fisher B, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med.

2002;347:1233-1241.

Hall L, Colantonio A, Yoshida K. Barriers to nutrition as a health promotion practice for women with disabilities.

Int J of Rehabilitation Research.

2003;26:245-247.

Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of biolateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med.

1999;340:77-84.

Herrera JE, Stubblefield MD. Rotator cuff tendonitis in lymphedema: a retrospective case series. Arch Phys

Med Rehabil.

2004:85:1939-1942.

Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA.

2005;293:2479-2486.

Hughes RB. Achieving effective health promotion for women with disabilities. Family & Community Health.

2006;29:44S-51S.

Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: a summary of the evidence for the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med.

2002;137:344-346.

Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J of Public Health.

2000;90:955-961.

Irwig L, Houssami N, van Vliet C. New technologies in screening for breast cancer: a systematic review of their accuracy. Brit J Cancer . 2004;90:2118-2122.

Ismail J, Chen BE, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS. Breast cancer mortality trends in the United States according to estrogen receptor status and age at diagnosis. J of Clin Oncology.

2007;25:TK-TK.

Kaplan C, Richman S. Informed consent and the mentally challenged patient. Contemporary Ob/Gyn.

2006;51:63-72.

Kauff ND, Domcheck SM, Friebel TM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of

BRCA1 - and BRCA2 -associated breast and gynecologic cancer: a multicenter, prospective study. J Clin

Oncology. 2008:26:1331-13337.

Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the Breast

Cancer Follow-Up and Management Guidelines in the Adjuvant Setting. J Clin Oncology. 2006;24:5091-5097.

Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Review: regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;2:CD003373.

Li L, Ford JA. Triple threat: alcohol abuse by women with disabilities. Applied Behavioral Sci Rev.

1996;4:99-109.

Lostumbo L, Carbine N, Wallace J, Ezzo J. Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

2004;4:CD002748.

McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Roetzheim RG, et al. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and survival for women with disabilities. Ann Intern Med.

2006;145:637-645.

McDonald S, Saslow D, Alciati MH. Performance and reporting of clinical breast examination: a review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin . 2004;54:345-361.

McNeely JL, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP,Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast ancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ.

2006:175-34-41.

McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. JAMA.

2003;290:1331-1336.

Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WL, et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med.

2001;345:159-164.

Mele N, Archer J, Pusch BD. Access to breast cancer screening services for women with disabilities. JOGNN.

2005;34:453-464.

Moore RF. A guide to the assessment and care of the patient whose medical decision-making capacity is in question. Medscape General Medicine. 1999;1:(3). Available at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408024_1 .

Myers MF, Change M-H, Jorgensen C, et al. Genetic testing for susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer: evaluating the impact of a direct-toconsumer marketing campaign on physicians’ knowledge and practices.

Genetics in Medicine.

2006;8:361-370.

National Cancer Institute. Breast cancer (PDQ): treatment. Available at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional .

National Cancer Institute. Ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast cancer (PDQ): treatment. Available at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/HealthProfessional/page5.

National Cancer Institute. Estimating breast cancer risk: questions and answers. Updated September 5, 2006.

Available at www.cancer.gov/Templates/doc.aspx?viewid=ac1e8937-d95b-4458-a78a-1fe33dbfcbdc.

National Cancer Institute. Lymphedema after cancer: how serious is it? NCI Cancer Bulletin.

2007;4:5-6.

National Cancer Institute. Tamoxifen: questions and answers. Reviewed May 13, 2002. Available at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Therapy/tamoxifen .

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast

Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Guidelines. V.1.2007. Risk factors used in the modified Gail Model; 2007.

National Survey of Women with Physical Disabilities. Recent research findings: findings on reproductive health and access to health care. Center for Research on Women with Disabilities, Baylor College of Medicine; 1996.

Available at www.bcm.edu/crowd/finding4.html

.

Nosek MA, Howland CA. Breast and cervical cancer screening among women with physical disabilities. Arch

Phys Med Rehabil.

1997:78 (12 Suppl 5):S39-44.

Nosek MA, Hughes RB, Petersen NJ, et al. Secondary conditions in a community-based sample of women with physical disabilities over a 1-year period. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

2006;87:320-327.

Office of the Surgeon General. Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of

Persons with Disabilities. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service; 2005.

Ohira T, Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Yee D. Effects of weight training on quality of life in recent breast cancer survivors: the weight training for breast cancer survivors (WTBS) study.

Cancer.

2006;106:2076-2083.

Paskett ED, Naughton MJ, McCoy TP, Case LD, Abbott JM. The epidemiology of arm and hand swelling in premenopausal breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention.

2007;16:775-782.

Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, Rosen PP. Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer.

2001;92:1368-1377.

Poulos AE, Balandin S, Llewellyn G, Dew AH. Women with cerebral palsy and breast cancer screening by mammography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

2006;87:304-307.

Randolph WM, Goodwin JS, Mahnken JD, Freeman JL. Regular mammography use is associated with elimination of age-related disparities in size and stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. Ann Intern Med.

2002;137:783-790.

Robson M, Offit K. Clinical practice: management of an inherited predisposition to breast cancer. N Engl J

Med.

2007;357:154-162.

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Hannan PJ, Yee D. Safety and efficacy of weight training in recent breast cancer survivors to alter body composition, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor axis proteins. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev.

2005;14:1672-1680.

Shapiro CL, Manola J, Leboff M. Ovarian failure after adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with rapid bone loss in women with early-stage breast cancer. J of Clin Oncology. 2001;14:3306-3311.

Smeltzer S. Preventive health screening for breast and cervical cancer and osteoporosis in women with physical disabilities. Family & Community Health. 2006;29:35S-43S.

Smith, RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer,

2005. CA Cancer J Clin.

2005;55:31-44.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer Screening in the United States, 2007: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:90-104.

Stubblefield MD, Custodio CM. Upper-extremity pain disorders in breast cancer.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil .

2006;S96-S99.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Public

Health Services; 2000.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility. September 2006. Available at www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsbrgen.htm#summary .

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002.

Vogel VG, Costantino JP, et al., for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs. raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the

NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial. JAMA.

2006;295:2727-2741.