Mycobacterial Infections

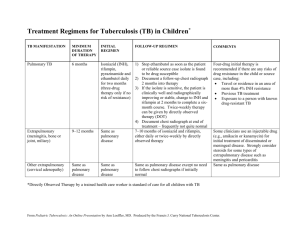

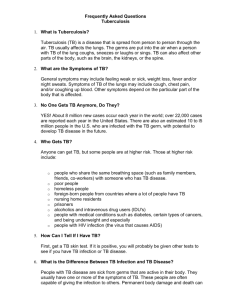

advertisement

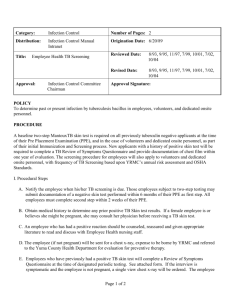

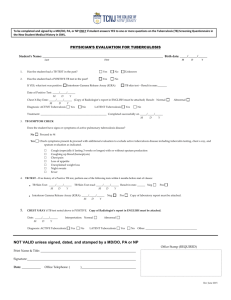

Mycobacterial Infections Robert F. Nash D.O. 2007 Mycobacterial Infections M. tuberculosis M. avium complex M. kansasii M. fortuitum M. chelonae/abscessus M. smegmatis History “The Consumption” Found in Skeletal remains from 4000 BC Hippocrates states this is the most wide spread disease of the time First sanitarium opened in 1859 in Poland BCG vaccine first used in 1921 60-80% effective in UK study 14% in Georgia and Alabama Pneumothorax technique Streptomycin 1946 M. tuberculosis Robert Koch in 1882 Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the etiologic agent of tuberculosis (TB) He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for his tuberculosis findings in 1905. He is considered one of the founders of bacteriology. 1/7 of all deaths in Europe Cellular Biology There is no true outer membrane in Mycobacterium Acid fast bacillus (AFB) Stains used in evaluation of tissue specimens or microbiological specimens include Fite's stain, Ziehl-Neelsen stain, and Kinyoun stain Generation time is about 20 to 24 hours. 20 minutes for e-coli Schematic diagram of Mycobacterial cell wall. 1. outer lipids 2. mycolic acid 3. polysaccharides (arabinogalactan) 4. peptideglycan 5. plasma membrane 6. lipoarabinomannan (LAM) 7. phosphatidylinositol mannoside 8. cell wall skeleton M. tuberculosis Reportable disease 8 million new cases a year worldwide 3 million infected patients die a year 1953 - 84,304 cases 1985 - 22,201 1992 - 26,673 2005 - 14,093 Why ? Schneider E; Moore M; Castro KG (2005); Deterioration of tuberculosis program infrastructure, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and tuberculosis among foreign-born persons contributed to the resurgence. Epidemiology HIV Foreign born Prisoners Low socioeconomic class Cancer patients Celiac Disease Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists >15 mg of prednisone Children Pathophysiology Tiny aerosolized droplets inhaled from Patients with infectious TB. Infection either becomes: Latent Active Latent is not infectious Active IS INFECTIOUS Pathophysiology Possible outcomes Clearance 5-10%, lifetime risk, of exposed immunocompetent become infected 10% risk per year in immunocompromised patients Primary infection Chronic or latent infection Active disease many years after the infection (reactivation disease) Clinical manifestations Pulmonary infection Classic Constitutional symptoms Cough Blood tinged sputum Other symptoms Pleuritic chest pain Retrosternal and interscapular dull pain Extrapulmonary Infections Constitutional symptoms Site specific complaints Pleura Skeletal CNS Peritonium Kidneys and Adrenals Genitals GI Miliary Hematologic CV Diagnostic Testing Tuberculin skin test Intradermal placement Read 48-72 hours after placing 25% newly diagnosed TB will be negative Anergy Single step or two step testing (Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis (2000) from CDC) Two-step testing should be used for the initial skin testing of adults who will be retested periodically, such as health care workers Booster effect Guidelines for determining a positive tuberculin skin test reaction Induration >5 mm: HIV-positive persons Recent contacts of TB case Fibrotic changes on chest radiograph consistent with old TB, Patients with organ transplants and other immunosuppressed patients (receiving the equivalent of >15 mg/d Prednisone for >1 mo) Induration >10 mm: Recent arrivals (<5 yr) from high-prevalence countries Injection drug users, Residents and employees* of high-risk congregate settings: prisons and jails nursing homes and other health care facilities, residential facilities for AIDS patients, and homeless shelters, Mycobacteriology laboratory personnel, Persons with clinical conditions that make them high-risk: silicosis diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, some hematologic disorders (eg, leukemias and lymphomas), other specific malignancies (eg, carcinoma of the head or neck and lung), weight loss of >10 percent of ideal body weight, gastrectomy, jejunoileal bypassChildren <4 yr of age of infants, children, and adolescents exposed to adults in high-risk categories Induration >15 mm: Persons with no risk factors for TB * For persons who are otherwise at low risk and are tested at entry into employment, a reaction of >15 mm induration is considered positive. Potential causes of falsely negative tuberculin skin tests Factors related to the person being tested Infections Viral (HIV, measles, mumps, chickenpox) Bacterial (typhoid fever, brucellosis, typhus, leprosy pertussis, overwhelming tuberculosis, tuberculous pleurisy) Fungal (South American blastomycosis) Live virus vaccinations (measles, mumps, polio) Metabolic derangements (chronic renal failure) Low protein states (severe protein depletion, afibrinogenemia) Diseases affecting lymphoid organs (Hodgkin's disease, lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, sarcoidosis) Drugs (corticosteroids and many other immunosuppressive agents) Age (newborns, elderly patients with "waned" sensitivity) Recent (within the past 10 weeks) or overwhelming infection with M. tuberculosis Stress (surgery, burns, mental illness, graft versus host reactions) Factors related to the tuberculin used Improper storage (exposure to light and heat) Improper dilutions Chemical denaturation Contamination Adsorption (partially controlled by adding Tween 80)Factors related to the method of administration Injection of too little antigen Subcutaneous injection Delayed administration after drawing into syringe Injection too close to other skin tests Factors related to reading the test and recording results: Inexperienced reader, Conscious or unconscious biasError in recording Diagnostic Testing QuantiFERON®-TB Gold Test Test was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005 Blood test No booster effect Limited data available for use on children NAA Used if AFS is positive to rule out TB C-xray Pulmonary TB Classic Cavitary and/or infiltrative lesions in either upper lobe Granuloma’s Fibrosis Traction or enlargement of hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes 1/3 cases do not present typically Circ. 1935 Gold Standard Sputum/ Tissue culture Self induced BAL Induced Conde MB, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000 Dec;162(6):2238-40. Showed both BAL and Induced to have 100% specificity and 38% and 34% sensitivity, respectively. Treatment Latent: 9 months of Isoniazid 4 months of Rifampin Active: 4 drug Regiment for 2 months Isoniazid Rifampin Pyrazinamide Ethambutol 2 drug Regiment for 4 or seven months Isoniazid Rifampin Labs Baseline and routine laboratory monitoring during treatment of LTBI are indicated only when there is a history of liver disease, HIV infection, pregnancy (or within 3 months post delivery), or regular alcohol use. Baseline hepatic measurements of serum AST, ALT, and bilirubin are used in the situations mentioned above and to evaluate symptoms of hepatotoxicity. Frequent Drug Reactions Isoniazid Hepatotoxicity B6 depletion INH increases blood levels of phenytoin (Dilantin) and disulfiram (Antabuse) Rifampin Hepatotoxicity Orange/red body fluids Decreases blood levels of many drugs including oral contraceptives, warfarin, sulfonureas, and methadone Contraindicated in HIV-infected individuals being treated with protease inhibitors (PIs) and most Frequent Drug Reactions Pyrazinamide Hepatotoxicity Thrombocytopenia Interstitial Nephritis Ethambutol Hepatotoxicity Optic Neuritis Resolution 3 negative sputum cultures Response to AB therapy Improvement in Chest radiograph (Pt with pulmonary TB) Infection control Negative Pressure Isolation Room (NPIR) Protective mask (N95) Patient instructed to cover mouth and nose when coughing, with tissue M. avium complex MAC Several different syndromes are caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). Disseminated infections are usually associated with HIV infection. Less commonly, pulmonary disease in nonimmunocompromised persons is a result of infection with MAC. In children, the most common syndrome is cervical lymphadenitis. Hot tub associated hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In HIV infected persons, manifestations include night sweats, weight loss, abdominal pain, fatigue, diarrhea, and anemia. American Thoracic Society (ATS) Guidelines Treatment: A regimen of daily clarithromycin (500 mg twice a day) or azithromycin (250 mg), rifampin (600 mg) or rifabutin (300 mg), and ethambutol (25 mg/kg for two months, then 15 mg/kg) is recommended for therapy of adults not infected with the HIV virus. Streptomycin two to three times per week should be considered for the first eight weeks as tolerated. Patients should be treated until culture-negative on therapy for one year. Prophylaxis: CD4 counts < 50 cells, especially with a history of a prior opportunistic infection. Rifabutin 300 mg/d, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, azithromycin 1,200 mg once weekly and azithromycin 1,200 mg once weekly plus rifabutin 300 mg daily are all proven effective regimens. M. kansasii The most common presentation of M kansasii is a chronic pulmonary infection that resembles pulmonary tuberculosis. It may also infect other organs. Incidence of infection has increased because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It is the second most common nontuberculous, opportunistic mycobacterial infection associated with AIDS, surpassed only by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). ATS Guideline: Regimen of daily isoniazid (300 mg), rifampin (600 mg), and ethambutol (25 mg/kg for 2 months, then 15 mg/kg) for 18 months with a minimum of 12 months' culture negativity is recommended for pulmonary disease in adults caused by M kansasii. Clarithromycin or rifabutin will need to be substituted for rifampin in HIV-positive patients who take protease inhibitors. M. fortuitum Local cutaneous disease, osteomyelitis, joint infections, and ocular disease (eg, keratitis, corneal ulcers) may occur after trauma. M fortuitum is a rare cause of isolated lymphadenitis. Disseminated disease, usually with disseminated skin lesions and soft tissue lesions, occurs almost exclusively in the setting of severe immunosuppression, especially AIDS. Endocarditis has been documented. M. chelonae/abscessus M abscessus is increasingly recognized as a persistent pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis. Disseminated disease, usually with disseminated skin and soft tissue lesions, occurs almost exclusively in the setting of immunosuppression, especially AIDS lung disease Surgical site infections due to M chelonae ATS Guideline: Therapy of nonpulmonary disease caused by M fortuitum, M abscessus, and M chelonae should include drugs such as amikacin and clarithromycin, based on in vitro susceptibility tests. What medication(s) do you use to initiate treatment of active pulmonary Tuberculosis? Isoniazid Rifampin Pyrazinamide Ethambutol All the above Negative Tuberculin test rules out TB. a) True b) False TB is considered non-infectious when, Patient has: a) 3 negative sputum cultures b) Response to AB therapy c) Improvement in Chest radiograph (Pt with pulmonary TB) d) All the above References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in the United States. AUSchneider E; Moore M; Castro KG SOClin Chest Med 2005 Jun;26(2):183-95. TIA century of tuberculosis. AUMurray JF SOAm J Respir Crit Care Med 2004 Jun 1;169(11):1181-6. Brock, TD. Robert Koch — A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. Science Tech Publishers, Madison, 1988. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. AUMenzies D SOAm J Respir Crit Care Med 1999 Jan;159(1):15-21. Comstock GW, Palmer CE. (1966). "Long-term results of BCG in the southern United States". Am Rev Resp Dis 93 (2): 171–83. Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, et al. (1994). "Efficacy of BCG Vaccine in the Prevention of Tuberculosis.". J Am Med Assoc 271: 698–702. ©2007 UpToDate® • www.uptodate.com Licensed to Lake Erie College SupportTag: [WEB006-208.12.102.170-0DDE3B1234-2347.2330] Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:1376. Copyright© 2000 The American Thoracic Society. Holden M, Dubin MR, Diamond PH. Frequency of negative intermediate-strength tuberculin sensitivity in patients with active tuberculosis. New Engl J Med 1971;285:1506-09. Nash DR, Douglass JE. Anergy in active pulmonary tuberculosis. A comparison between positive and negative reactors and an evaluation of 5 TU and 250 TU skin test doses. Chest 1980;77:32-7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:603 Conde MB; Soares SL; Mello FC; Rezende VM; Almeida LL; Reingold AL; Daley CL; Kritski AL Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000 Dec;162(6):2238-40. Poulsen, A. Some clinical features of tuberculosis. 2. Initial fever 3. Erythema nodosum 4. Tuberculosis of lungs and pleura in primary infection. Acta Tuberc Scan 1951; 33:37. CDC wesite The American Thoracic Society, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156:S1