AP History 10 Chapter 9 Lecture Notes I. The American Industrial

AP History 10 Chapter 9 Lecture Notes

I. The American Industrial Revolution

A. The Division of Labor and the Factory

1. Labor – Mass production enabled products that had been luxury items to be consumed by all. During the 1820s and 1830s, merchants in the Lynn, Massachusetts shoe industry introduced an outwork system with a division of labor; some work was performed by semiskilled laborers, and the rest by women working in their homes; workers’ wages declined as more jobs were now available; increased production and lowered costs to consumers.

2. The factory – Was built for production that was not suitable for the outwork system; concentrated production in one location/building; division of labor was utilized; Cincinnati merchants built slaughterhouses that divided labor among workers efficiently and increased output; use of water power started in the 1780s; by the 1830s, factories used minerals such as coal instead of water.

B. The Textile Industry and British Competition

1. American and British Advantages – British feared competition from U.S. manufacturers; prohibited mechanics from emigrating for fear they would give away secrets of British industry; in 1789, émigré mechanic Samuel Slater built a mill in Rhode Island credited with starting the Industrial Revolution;

British had the advantage of inexpensive shipping, low interest rates, and cheap labor from a large population; Americans got help from tariff bills aimed at driving up the costs of imports.

2. Better Machines, Cheaper Workers – Americans improved upon British technology and recruited young women from farm families as laborers; cities like Lowell, MA, had boardinghouses for the girls with cultural events, moral instruction, and strict rules—known as the Waltham-Lowell System; women had decent living conditions and independence compared to farm life; factories could undersell British competitors with these lower wages.

C. American Mechanics and Technological Innovation

1. Mechanics – By the 1820s, American mechanics were developing innovative factory technology; were not formally educated but skillful. The Sellars family in Pennsylvania developed a machine to twist woolen yarn and then later built a machines to weave wire sieves; also ran machine shops that built fire hoses, papermaking equipment, and eventually locomotives; the Sellars family and other mechanics founded the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia for instruction in chemistry, math, and mechanical design.

2. Tools – American craftsmen pioneered the development of machine tools—machines that made parts for other machines; Eli Whitney studied at Yale and developed the cotton gin from technology he devised from women’s hair pins; later Whitney built machine tools to produce interchangeable musket

parts; early 19th century saw inventions such as lathes, planers, and boring machines; these inventions helped to increase output beyond the British system.

D. Wageworkers and the Labor Movement

1. Free Workers Form Unions – Outwork and factory system began to replace craft workers; workers received a wage and direction from an employer; working-class men disliked referring to employers as

master and instead used the Dutch word boss; traditional crafts that required specialized skills

(carpenters, stonecutters, masons, cabinetmakers) provided a sense of identity that helped men to organize in unions that could then bargain with employers; some artisans left urban areas to set up shops in the country and avoid factory work; both Britain and the U.S. viewed unionization as illegal.

2. Labor Ideology – During the 1830s, shoemakers in Lynn, MA, who were not allowed to organize formed a mutual benefit society; others followed, bringing workers together on common ground; in

1834, National Trade Union formed as first regional union of different trades; in Commonwealth v. Hunt

(1842), Supreme Court ruled that unions were not illegal and workers could unionize and strike to enforce a closed-shop agreement; union leaders condemned employers and advocated a labor theory of value. Under this theory, the price of goods should reflect the cost of the labor required to make them, and the income from their sale should go primarily to the producers; in 1836, union activists organized nearly 50 strikes for higher wages in the U.S.; striking women workers in New Hampshire won some relief. Increasingly, young New England women refused to enter the mills and were replaced by poor immigrants.

II. The Market Revolution

A. The Transportation Revolution Forges Regional Ties

1. Canals and Steamboats Shrink Distance – State governments paid private companies to build toll roads (“turnpikes”); in 1806, Congress appropriated money for a National Road built of compacted gravel; the project began in Maryland in 1811 and reached modern-day West Virginia in 1818, ending in

Illinois by 1839. Land travel was slow so states turned to increasing water travel; Erie Canal connected the Hudson River to Lake Erie; was an enormous project for engineers and mostly Irish workers; changed the ecology of the region, as farming communities were built along the waterway and exploited natural resources. The Erie Canal was a huge economic success that encouraged further building of canals in the nation; by 1848, it was possible to travel an all-water route from NYC to New Orleans; steamboats were utilized for travel and transport.

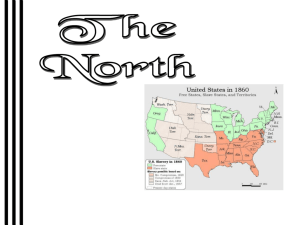

2. Railroads Link the North and Midwest – New York, Boston, and London capitalists invested in the railroad industry; a boom in the 1850s expanded commerce; Chicago grew as a result of ability to transport goods produced in the Midwest via railroad; midwestern farmers could export their crops to the East and to Europe; factories such as John Deere’s manufacturing of farming equipment grew in the region; Northeast and Midwest had diverse economies, while the South remained tied to agriculture.

B. The Growth of Cities and Towns

1. West and Midwest – Urban population in U.S. grew substantially; towns grew around factories; those cities that started as locations of commerce eventually grew to be manufacturing centers (Chicago and

St. Louis) and transit centers (Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, New Orleans).

2. Atlantic coastal cities – Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore remained important for import/export but also became financial centers; populations grew as a result of immigration to port cities; New York became the hub for exporting cargo, mail, and people to Liverpool and London,

England.