baldwin

advertisement

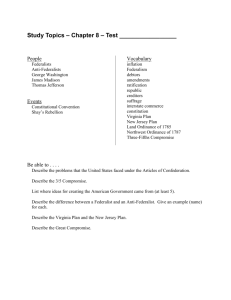

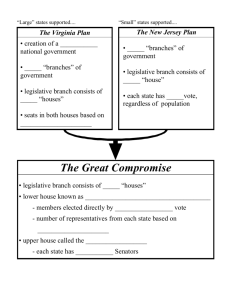

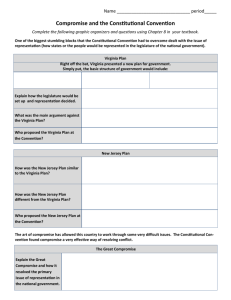

Few and Baldwin- Andrew Lewis Let’s take some time to imagine some things. Imagine the year is 1789. Imagine you’re back in a time where Constitutional Congress is being held, Georgia is still under its original constitution of 1777, George Washington isn’t President yet, and Snuggies haven’t been invented (You could not pick up the TV remote without getting your arms cold, but that’s ok, because TVs haven’t been invented either). Imagine you are attending the Continental Congress, and yes, your arms are cold. The meeting is being held, in case you don’t know, because there are major flaws in the Articles of Confederation, a document signed as our first constitution. The only semi-good thing in the Articles is that every state had equal votes, which many states still didn’t like. However, there were plenty of bad things. For one, it created a very weak central government. With the Articles of Confederation our government had no president, no court system, couldn’t impose taxes, couldn’t regulate trade, and had no central army. That means if New York invented a blanket with the ability to warm our arms without the inconvenience of carrying it around or tripping over it, it would have no way to be sold in Georgia. So there you have it. We need to patch up a few problems in the Articles. Which is why the Continental Congress met. Every state except Rhode Island sent delegates. Why not Rhode Island? Good question. The thing is: Rhode Island was a small state. It was happy with its militia, did not need to trade with other states, and it had the same vote as Texas or Virginia. Rhode Island wasn’t going to have anything to do with changing that. Anyway, back to the Continental Congress. Georgia sent 4 delegates, who went there with two goals: to keep slavery, and to make a stronger central government. Georgia wanted a stronger central government to help them fight against the Native Americans, because their state militias were loyal to the counties alone. Hmm, looks like they might need a president. You might think that there are enough problems to be solved with the Articles of Confederation. But there can never be too many failures in a prototype. Like the original sleeveless blanket. The Articles stated that each state got equal votes. This was very good for Rhode Island, but for states like Virginia it was very unfair. Why should the thousands of people in Virginia get the same say as the hundreds of people in Rhode Island? Unfortunately, the smaller states had a similar argument. They had a just as big of a legislature, just as important a governor, why should what they want count for less? It was a bit of a clash. A man named James Madison, from Virginia, drafted a plan for this before the Convention began. It was called the Virginia plan, and stated that the government would have three branches, and the legislative branch would have two houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives, and both these houses would be represented based on population. But this could not be agreed on, because it still placed the smaller states at a disadvantage. A delegate from New Jersey, William Patterson, drafted a counter plan. This was called the New Jersey plan, and it stated that the government would have a unicameral legislature, with the power to levy taxes, regulate trade, and make laws. His idea was that representation be equal. The main problem with the Virginia plan was that it still favored only the large states, and while it ensured all power was equal, it also gave the branches very little power. But the 1 Few and Baldwin- Andrew Lewis New Jersey plan was by no means perfect. Unlike the Virginia plan, it did not state a completely new constitution. Under the New Jersey plan, it would be very much like continuing under the Articles of Confederation, and it favored the small states. As obvious as it was that blankets needed arms, it was even more obvious that the plans needed to be combined, to get the best of both plans. But just as snuggies were not invented, nobody except Abraham Baldwin and William Few, two of the Georgia delegates, saw what needed to be done. The delegates in the Congress decided to vote between the two plans. The voting continued small state vs. large state. Georgia was the last state to vote. When the vote came to Georgia, the Virginia and New Jersey plans were tied. William Few voted for the Virginia, which was the plan better suited to fit Georgia’s needs. However, when it was Abraham Baldwin’s turn to vote, he did not vote for the good of Georgia. He voted for the good of America as a whole. He voted for the New Jersey plan. Because of that vote, both plans were tied, and the convention had to make a compromise. Not just a compromise; The Great Compromise. The Convention decided to combine what they felt were the best each plan. Of course, both plans had three branches in the government, so that was easy. And then the legislature. The delegates couldn’t figure out how much power the legislature should have, but they agreed that the legislature should be bicameral, like in the Virginia plan. This legislature would have the ability to levy taxes, regulate trade, and make laws, like in the Rhode Island plan. It went on like this, creating a very good constitution for the new U.S. but then came the problem of representation. It wouldn’t be fair to have representation entirely either based on population or equal vote, but the delegates saw no way to combine them as they had the rest of the constitution. After much mulling it over with cold arms and no blanket to conveniently cover them, one of the delegates brought up the Virginia plan’s bicameral legislature: The House of Representatives and the Senate. They had two forms of representation to fit in, and two houses to fit them into. So why not have one house use the Virginia plan’s idea of population representation, and the other house use the Rhode Island plan’s idea of equal representation. Great idea, right? It was so good it stuck for a few hundred years in the U.S. government, and that was with cold arms too. But no good thing can last. Shortly afterwards there came a question from the southern states. Now that they were to be represented by population (in the House of Representatives at least), would slaves count as a part of the population? It was just like big state vs. small state all over again, this time slave-owners vs. non slave-owners. It wouldn’t be fair to the non slaveowners if slaves counted, but it wouldn’t be fair to slave-holders if none of the slaves counted. But they’d learned something Abraham Baldwin and William Few: When all else fails, compromise. They made something called the Three/ Fifths Compromise. It said that three out of five slaves would count for representation. That way the salve-owners would receive compensation for accommodating slaves, but non slave-owners wouldn’t be at a disadvantage. Everyone learned a lesson that day. The states learned how to get along, the delegates learned how to compromise, and you learned that I deserve a 105 for the Snuggie references. Right? 2 Few and Baldwin- Andrew Lewis 3