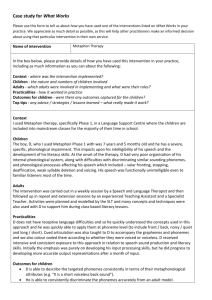

li6 1 phonemes and abstract reps SHORT

advertisement

Li/Lt6

Phonology and Morphology

Lecture 1

Phonemes and abstract representations

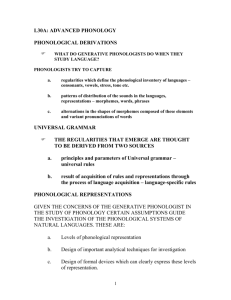

Today’s topics

Two theories of mind

Evidence for abstract mental representations

Competence vs performance

Priming

Phonological alternations

Evidence for phonemes

Neutralization

Language games

Speech errors

Loanword phonology and L2 transfer

Orthography

Perception

Discrimination tasks

Two theories of mind

rationalist

reductionist

learning that

learning to

whole > sum of parts

WYSIWIG

abstract, multi-level

concrete, surface level only

symbol-manipulating rules and

constraints

connectionist network +

statistical knowledge

Turing machine

switch network

categorical, symbolic

gradient, numerical

The reductionist position

Popular lay intuition that we store and manipulate surface

forms

Priming effects by individual voice

“Once we introduce mechanisms for describing word-word

correspondences into the grammar, it may be possible to

dispense with underlying representations altogether (see

proposals by Burzio 1998, Bybee 2001).” (Sumner 2003)

connectionists

Evidence for

abstract URs

Psychological reality:

Sapir 1933

Basic points:

speech sounds are stored in the mind as abstract categories

(phonemes)

These are not always identical to their surface manifestations

((allo)phones)

Speakers think of language in terms of phonemes, not phones

(i.e. phonemes have psychological reality)

1.

2.

3.

oak tree

maple tree

Evidence:

Spelling: Alex Thomas (Nootka)

1.

•

•

writes <ħi, ħu> for [ħε, ħ]

writes <C!> for 2 different things he was taught (T!, ’R)

Intuitions

2.

•

NB Sapir needs

external evidence to

decide if the two

forms he hears as

identical are actually

different phonetically

•

Southern Paiute

•

•

•

Tony says [pABAh] for ‘at the water’

Asked to divide the word into syllables, he says [pA ] [pAh]

/p t k/ [β r γ] / V _; no /β r γ/

Sarcee

•

John Whitney feels that dìníh ‘it makes a sound’ has a final /t/, whereas

dìníh ‘this one’ does not (cf. dìníth - í ‘the one who…’)

TREE

TIN

k!

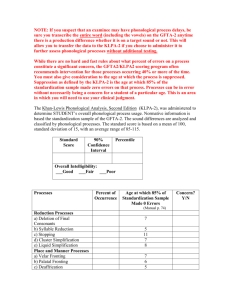

L1 competence : performance

“by the time infants are starting productive use of language they

can already discriminate almost all of the phonological contrasts of

their native language. While they cannot yet produce adult-like

forms, they appear, in many respects, to have adult-like

representations, which are reflected, among other things, in their

vociferous rejections of adult imitations of their phonologically

impoverished productions” (Faber and Best 1994:266-7)

Did you say

TINk?

“Preferential Looking” paradigm (Hirsh-Pasek

and Golinkoff 1993)

• 19-month old infants’ comprehension of

sentence like “Big Bird is hugging Cookie

Monster. Where is Big Bird hugging Cookie

Monster?”

• Infants (who can’t speak yet) looked

longer at correct video

Cruttenden

1985

No!!

competence vs. performance

intoxicated speech of the captain of the Exxon Valdez

(Johnson, Pisoni, and Bernacki 1990)

Observed effects:

• misarticulation of /r/ and /l/

• final devoicing

• Deaffrication

Performance problem, not different grammar

attempts at producing adult [phεn] pen collected from a 15month-old child in a 30-minute period (Ferguson 1986):

[mãə], [v], [dεdn], [hIn], [mbõ], [pHIn], [tHntHntHn],

[bah], [dhau], [buã]

competence vs. performance

Bedore, Leonard, and Gandour 1994

4 yr old girl substitutes dental click for {s z S Z tS

dZ}

She can initially imitate the fricatives, but not produce them

on her own

After a short training session, she starts to produce [s]

correctly

She then immediately gets all the others right

“the rapid rate of change observed in the child’s

phonological system seems consistent with a phonological

learning model in which the child has adult-like underlying

phonological representations” (283)

Priming

Colloquial Dutch optionally neutralizes

obstruent voicing with the clitic -der ‘her’

Do speakers respond faster to targets that

match the voicing of a prime?

Lexical decision task, with following

sequence of events:

1.

2.

3.

PRIME

TARGET

DECISION

(verb+clitic construction)

(verbal infinitive or nonword)

(is the target a legitimate word of Dutch?)

Results

/ık kœs der/ ‘I kiss her’ [ık kœzdər] ~ [ık kœstər]

/ık kiz der/ ‘I kiss her’ [ık kizdər] ~ [ık kistər]

Responses were faster when voicing of prime

corresponded to voicing of UR

Conclusion

Both variants of a verb are not stored in the

lexicon

Jongman, Allard. 2004. Phonological and Phonetic Representations: The Case of Neutralization. Proceedings of the 2003 Texas Linguistics Society Conference:

Coarticulation in Speech Production and Perception, Augustine Agwuele, Willis Warren, and Sang-Hoon Park, eds., pp. 9-16.

Japanese g~ŋ and rendaku

(Ito and Mester 2003)

Rendaku: C [+voi] / ]+[ __ X]

Lyman’s Law: X does not contain [+voi, -son]

taba ‘bundle’ satsu+taba ‘wad of bills’ (*satsu-daba)

g-weakening: non-initial /g/ [ŋ]

kami-kaze vs. ori-gami

[gai+jiN] ‘foreigner’

[koku+ŋai] ‘abroad’

Rule interaction

R feeds GW: /ori+kami/ [oriŋami]

R counterfeeds GW: /saka+toge/ ‘reverse thorn/ [sakatoŋe]

If GW preceded R it would

change g to ŋ and thereby feed

R, resulting in *sakadoŋe

Evidence for

abstract phonemes

Phonemes are also abstractions

Ambiguity: German devoicing

Rad

Rat

nom.

[

At]

gen.

[Ads]

[Ats]

[] = voiced uvular

fricative cf. French, Hebrew

Perception

Categorical perception: VOT

Categorization functions for synthetic stimuli ranging from [b] to [p]. Open circles indicate the percent of

times that each stimulus was perceived as [b], and the filled circles indicate the percent of times that each

stimulus was perceived as [p]. (Lisker and Abramson 1970)

Hearing Cs that aren’t there I:

The McGurk effect

When hearing the sound BA, while seeing GA:

most adults (98%) think they are hearing DA

McGurk, H. and MacDonald, J. 1976. Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature 264:746-8.

Hearing Cs that aren’t there II:

V formants C

Identification of

burstless stops

with different

vowels:

transitions

are

all you

need!

Delattre, Liberman, & Cooper (1955) JASA 27, 769-773

Phonemes vs. allophones

t : th in English (allophonic) vs. Thai

(phonemic)

Speakers produce consistent and finely controlled

distinctions between allophones

When measured experimentally, subjects typically

distinguish allophones at above chance levels, but

much less easily and well than phoneme pairs

• for aspiration in English, see Pegg & Werker 1997,

Whalen et al. 1997, Utman et al. 2000, Jones 2001

L2 transfer

Phoneme vs. allophone

Phonemes can distinguish

meaning (flight : fright)

Allophones don’t

Orthography

Phonological mediation

In semantic disambiguation tasks, the phonology of a word

interfered with the disambiguation process even when the

reader had access to its semantic representations (Van

Orden 1987).

reader was presented with IS THIS A FLOWER?

followed by the presentation of ROWS

Correct response accuracy for such sentence-target pair

was significantly lower when the targets shared a

phonological representation with a word neighbor that

semantically fit the question (i.e., ROSE).

when the subject had the ability to resolve the task with the

correct answer (NO) phonological information intervened.

Letter priming

Lee

and Turvey 2003

forms

with deleted silent letters (SALM,

COLUM) prime better than forms with deleted

pronounced letters (COUSI)

Conclusion: phonological representations are

activated during visual word recognition.

Speech errors

Types of speech errors

Language games

Backwards English

Cowan & Leavitt 1992 study of one woman

Example: garage [graž] reversed as [žarg]

Evidence that she reverses phonemes (rather than

letters):

• 1. no silent letters pronounced in reverse forms

• 2. homographs were always pronounced differently (two

<g>'s in garage)

Not functioning as reversed tape recorders:

• Compound units (diphthongs and affricates) were

consistently preserved as units rather than being

reversed.

• choice [tšojs] was reversed as [sojtš] (rather than *[sjošt])

Verlan

Procedure

Invert syllables (in polysyllabic words)

• L’envers ‘the reverse’ → [verlan], femme ‘woman’ → meuf

• Cf. Spanish Vesre, which inverts syllable order, e.g. muchacho → chochamu

What to do with monosyllables?

Include final optional schwa, if there is one

moi [mwa] ‘me’ → ouam [wam]

fou [fu] ‘crazy’ → ouf

Viens chez ouam soir-ce y'a une teuf de ouf, je suis avec l'autre

nasbo, j ai du sky et la race de beuh

‘Come to my place tonight there is a huge party, I'm with this hot chick,

I've got some whiskey and a lot of weed’

teuf - fête ‘party’, nasbo = bonasse ‘hot chick’, sky = whiskey, beuh =

herbe ‘weed’

Key for us: monosyllables inversion of phonemes

Drop final vowel

Conclusions

Words are not acoustic signals, but rather abstract

mental representations of language.

Words in turn are composed of abstract

phonemes, which are again abstract mental

symbols rather than elements of the physical

world.

References

Bedore, L., L. Leonard, and Jack Gandour. 1994. The substitution of a click for sibilants: a case study. Clinical linguistics & phonetics 8.4:283-293.

Bishop, D. and J. Robson. 1989. Accurate non-word spelling despite congenital inability to speak: phoneme-grapheme conversion does not require subvocal articulation. British

Journal of Psychology 80.1:1-13.

Burzio, Luigi. 1998. Multiple Correspondence. Lingua 104:79-109.

Bybee, Joan. 2001. Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cowan, Nelson & L. Leavitt. 1992. Speakers' access to the phonological structure of the syllable in word games. In M. Ziolkowski, M. Noske, & K. Deaton (eds.), Papers from the

26th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Volume 2: The Parasession On the Syllable in Phonetics and Phonology. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Cruttenden, Alan. 1985. Language in infancy and childhood, second edition. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Delattre, P., Alvin Liberman, & F. Cooper. 1955. Acoustic loci and transitional cues for consonants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 27.4:769-773.

Faber, Alice & Cathi Best. 1994. The perceptual infrastructure of early phonological development. In R. Corrigan, G. Iverson, & S. D. Lima, eds., The reality of phonological rules,

pp. 261-280. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ferguson, Charles. 1986. Discovering sound units and constructing sound systems: it’s child’s play. In Invariance and variability of speech processes, Joseph Perkell and Dennis

Klatt, eds., 36-51. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hirsh-Pasek, Kathy, & Roberta Golinkoff. 1993. Skeletal supports for grammatical learning: What the infant brings to the language learning task. In C. K. Rovee-Collier & L. P.

Lipsitt, eds., Advances in infancy research, Vol. 8, pp. 299-338. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Ito, Junko and Armin Mester. 2003. Japanese morphophonemics: markedness and word structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Johnson, Keith, Dominic Pisoni, and R. Bernacki. 1990. Do voice recordings reveal whether a person is intoxicated? A case study. Phonetica 47.3-4:215-37.

Jongman, Allard. 2004. Phonological and Phonetic Representations: The Case of Neutralization. Proceedings of the 2003 Texas Linguistics Society Conference: Coarticulation in

Speech Production and Perception, Augustine Agwuele, Willis Warren, and Sang-Hoon Park, eds., pp. 9-16.

Krifi et al. 2003: phonological features shared between (phonological correspondents of) graphemes increase priming effects

Lee, Chang and M. Turvey. 2003. Silent Letters and Phonological Priming. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 32.3:313-333.

Lisker, Leigh and Arthur Abramson. 1970. The voicing dimension: some experiments in comparative phonetics. Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Phonetic

Sciences (1967), Prague.

McGurk, H. and MacDonald, J. 1976. Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature 264:746-8.

Olson, A. and Alfonso Caramazza. 2004. Orthographic structure and deaf spelling errors: syllables, letter frequency, and speech. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A

57.3:385-417.

Pegg, J. & Janet Werker. 1997. Adult and infant perception of two English phones. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 102:3742–3753.

Piras, F. and P. Marangolo. 2004. Independent access to phonological and orthographic lexical representations: a replication study. Neurocase 10.4:300-7.

Remez, R., P. Rubin, D. Pisoni, and T. Carrell. 1981. Speech perception without traditional speech cues. Science 212:947-50.

Sapir, Edward. 1933. La réalité psychologique des phonèmes [The psychological reality of phonemes]. Journal de Psychologie Normale et Patholoique 30:247-265. [Reprinted in

English translation in his 1949 selected writings.]

Sumner, Megan. 2003. Testing the abstractness of phonological representations in Modern Hebrew weak verbs. Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at Stony

Brook.

Van Orden, G. 1987. A ROWS is a ROSE: spelling, sound, and reading. Memory and Cognition 15.3:181-198.