Charles Darwin 1809-1882 - Department of Biology

Charles Darwin

1809-1882

Descent with Modification

And the Origin of Species

Born 12 February 1809

Charles Darwin at age 31

Full-scale replica of the Beagle sailing off the coast of South America.

General plan of the Beagle based on a drawing by a shipmate during the voyage of the Beagle. Darwin wrote that, “I have just room to turn around and that is all.”

Voyage of HMS Beagle –1831-1836

A five year, circumnavigation of the globe, with the principal objective to map the coast line of South America.

Galapagos Islands

Darwin’s

Finches

.

Voyage of HMS Beagle –1831-1836

A five year, circumnavigation of the globe, with the principal objective to map the coast line of South America.

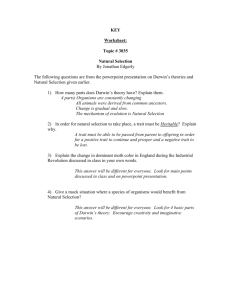

The Darwinian Thesis

Fact 1. Organisms have enormous reproductive potential

(Malthus)

Exponential growth

Time

Fact 2. Populations are at equilibrium (Observation)

Logistic Growth

Time

Fact 3. Resources are limited (0bservation).

If organisms have enormous reproductive potential, yet do not realize that potential owing to the fact that resources are limited, then there must be ….

Inference 1. … a struggle for existence.

Fact 4. Individuals are unique; there is individual variation.

(Observation)

Variation in shell color and banding pattern within a single species of

Caribbean snail.

Darwin was impressed with the fact that no two individuals are exactly alike.

In contrast to the Platonic idea that the eternal idealized type was what mattered, Darwin made individual variation an integral part of his theory of evolutionary change.

Inference 2. If there is a struggle for existence and there is individual variation, then some individuals, owing to their unique set of traits, will be better equipped to prevail in the struggle for existence. In other words,

NATURE SELECTION will occur.

Fact 5. Some individual variation can be transmitted from one generation to the next (personal observation, experience with animal breeding).

Offspring resemble their parents, but not precisely.

Thus, differences among individuals in the parental generation tend to be reflected in individuals of the descendent generation.

Trait in Parents

Within species, each individual is unique. That is, for most biological traits there is individual variation. But what are the sources of this variation?

Imagine that you take a sample of Mockingbirds from the population that exists on the University of Miami campus.

Northern Mockingbird

You measure and record bill length on several hundred specimens, and then cast your data into a frequency distribution , just as instructors cast test scores into a frequency distribution

(the “curve”) for purposes of assigning grades.

Why aren’t all of the mockingbirds identical with respect to bill length? That is, what are the sources of variation in bill length in this population?

Bill Length

Sources of Variation

• Sexual Dimorphism -- differences due to sex

• Ontogenetic Variation -- differences due to age

• Environmental Effect -- differences due to environment

• Artifactual Variation -- Imprecision in measurement

• Genetic Variation -- Variation due to genetic differences among individuals

Parental

Generation

Offspring

Only birds with large bills are allowed to reproduce and thus contribute to the next generation

By selecting birds with large bills to produce the next generation, we get a statistical response to this artificial selection : on average bill length in the descendent birds exceeds that of the parental generation. In addition, some individuals in the offspring generation exceed any in the parental generation in bill length.

Inference 3. Natural selection, operating over the immensity of

Geologic time, will produce evolutionary change, or DESCENT

WITH MODIFICATION

, to use Darwin’s expression.

IN SUMMARY: According to the Darwinian

Thesis, evolution proceeds by means of agents of natural selection , operating on heritable variation within populations, to bring about ancestor-descendant change.

That substantial changes can be induced in plants and animals by artificial selection is obvious. Consider the many very different breeds of dogs, all descended from a single ancestral species (the wolf).

But can we find examples of natural selection operating in nature?

Natural Selection in the House Sparrow, Passer domesticus.

• Native to Europe

• Introduced into North America at New York ca. 1850

• Spread Across North America,

• Presently ranges from northern

Canada to Oaxaca, Mexico

• A human commensal, hence the specific name, domesticus.

arriving in California by 1910

On 1 February 1898, in Providence, Rhode Island, an unusually severe winter storm killed or incapacitated a large number of

House Sparrows.

• One hundred-thirty-four dead or moribund house sparrows were brought to the laboratory of Professor Herman Bumpus.

• He divided the birds into those that were dead ( nonsurvivors ) and those that were alive when he received them

( survivors ).

• He then weighed each bird, measured total length and wingspan.

• He skeletonized all birds (survivors + non-survivors), so in truth there were no “survivors.” He measured various skeletal elements including those from the head, body, and appendages.

• He searched for differences in size and shape between survivors versus non-survivors.

• Bumpus published all of his original measurements.

Re-analysis of Herman Bumpus’ House Sparrow Data at the University of Kansas

Dr. Richard F. Johnston et al.

• Eliminated mass, wing-span and total length from analysis for being too imprecise in terms of measurement.

• Analyzed on the basis of skeletal measurements on the body, skull, and appendages

• Used a statistical analysis that combined the information contained in all of the measurements into a single over-all measure of size.

• Analyzed the sexes separately, as House Sparrows are known to exhibit sexual dimorphism , with males slightly larger, on average, than females.

Results of the Re-analysis of the Bumpus Data

Males Females

Large Small Large Small

Males

Likelihood of Surviving

Low

Medium

High

Very High

Smaller Larger

Body Size

Directional Selection favoring large body size in male House

Sparrows.

Selection in which individuals in one tail of the curve of variation have higher likelihood of survival (are “selected for”) is termed directional selection because over many generations, the average value of the trait (in this case body size), will shift in the same direction. Thus, in the Bumpus example, directional selection was operating on male House Sparrows to favor those with large body size.

Selection which operates more or less equally on both tails of the curve of variation is called stabilizing, or normalizing selection because under this mode of selection, the average value of the trait does not change. Variation in the trait will be reduced, however. In the Bumpus example, stabilizing selection was operating on females, favoring those of intermediate body size.

A third mode of selection, disruptive selection, occurs when individuals of intermediate value have a lower likelihood of surviving relative to those at either end of the curve of variation.

This is termed disruptive selection.

Results of the Re-analysis of the Bumpus Data

Males Females

Large Small Large Small

Females

Likelihood of Surviving

Very High

High

Medium

Low

Body Size

Larger

Stabilizing Selection favoring intermediate body size in House Sparrows.

Selection in which individuals in one tail of the curve of variation have higher likelihood of survival (are “selected for”) is termed directional selection because over many generations, the average value of the trait (in this case body size), will shift in the same direction. Thus, in the Bumpus example, directional selection was operating on male House Sparrows to favor those with large body size.

Selection which operates more or less equally on both tails of the curve of variation is called stabilizing, or normalizing selection because under this mode of selection, the average value of the trait does not change. Variation in the trait will be reduced, however. In the Bumpus example, stabilizing selection was operating on females, favoring those of intermediate body size.

A third mode of selection, disruptive selection, occurs when individuals of intermediate value have a lower likelihood of surviving relative to those at either end of the curve of variation.

This is termed disruptive selection.

Selection in which individuals in one tail of the curve of variation have higher likelihood of survival (are “selected for”) is termed directional selection because over many generations, the average value of the trait (in this case body size), will shift in the same direction. Thus, in the Bumpus example, directional selection was operating on male House Sparrows to favor those with large body size.

Selection which operates more or less equally on both tails of the curve of variation is called stabilizing, or normalizing selection because under this mode of selection, the average value of the trait does not change. Variation in the trait will be reduced, however. In the Bumpus example, stabilizing selection was operating on females, favoring those of intermediate body size.

A third mode of selection, disruptive selection , occurs when individuals of intermediate value have a lower likelihood of surviving relative to those at either end of the curve of variation.

This is termed disruptive selection.

Trait Value

Likelihood of Surviving

Very High

High

Medium

Low

Modes of Natural Selection

•

Directional selection : mean changes, variation is reduced (e.g., male House Sparrows in the Bumpus example).

• Stabilizing selection : mean does not change, variation reduced

(e.g., female House Sparrows in the Bumpus example).

• Disruptive selection : mean does not change, variation increased.

Historical Narrative Tracing the Development of

Darwin’s Ideas Concerning the Mechanism of

Evolutionary Change (cont.’d.)

• 1842 -- Brief unpublished abstract

• 1844 -- Unpublished essay of about 250 pages

• 1858 -- Received manuscript by Alfred Russel Wallace entitled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart

Indefinitely from the Ancestral Type.”

• 1858 -- Joint presentation of the theory of evolution by natural selection before the Royal Linnaean Society of London.

•

1859 -- Publication of “On the Origin of Species by Means of

Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life.”