Urban Sprawl DA – GDS 2012

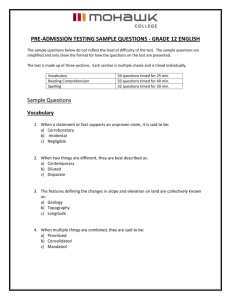

advertisement