IP Outline - St. Thomas More

advertisement

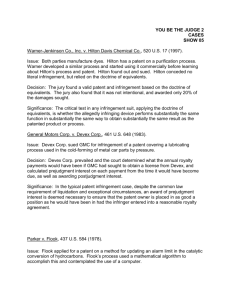

1 I. PATENTS 1. Elements A. Patentable Subject Matter, §101: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof may obtain a patent therefore...” Problem Areas: (i) Biopatenting Diamond v. Chakrabarty: Patentee claimed new living bacteria that were useful for oil cleanups. Ct found the wide scope of the rule limited only by laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas. Bacteria were patentable because of the human intervention/change. Parke-Davis v. Mulford: Patent for isolating adrenaline from a gland was enforceable because it was distilled to a level not found in nature. (ii) Algorithms, abstract ideas, laws of nature In re Bilski: Court found method for hedging risk in the commodities market invalid as a business method. However, patentable material does not need to be tied to a machine or transform a particular article into a different state or thing. Mayo v. Prometheus: Claimed patent was a diagnostic test that determined whether a dosage of medicine was too high or too low for a patient. Ct found this process invalid because the tests are naturally occurring. Including laws of nature does not make a process per se unpatentable – Ct must weigh the discovery and inhibition of future innovation, consider the substantial application and other limitations encompassed by the claim, etc. All patents will include a law of nature to some degree. B. Utility, §101 (i) Operable Utility (presumed) Does the invention actually work? This is rarely a hurdle and invoked only when the claims/specs are factually misleading, are incredible in light of prior art, or clear that it cannot work as claimed (perpetual motion devices). 2 (ii) Beneficial Utility (minimal requirement) Claims cannot be frivolous or injurious to well-being, good policy, or sound morals of society (nuclear weapons). Not the role of PTO to determine morals. Juicy Whip v. Orange Bang: Ct found a juice dispenser that pumped liquid from below rather than from the container above useful despite its fraudulent nature. There are times when imitation is useful – zirconiums, laminate flooring, etc. (iii) Practical Utility (eval’d at time of filing, utility req. with most bite) Invention must be useful for some specific and substantial realworld result. Brenner v. Manson: Patent claim was an analog for a known steroid that had tumor-inhibiting effects, and the process for synthesizing this analog steroid. Idea was that it too would have tumor-inhibiting effects. It satisfied the operable and beneficial requirements, but not the practical requirement. The effects are not positively known. Rule: Utility requires a specific (rather than “this gene is a probe,” requires, “this gene is useful for detecting X because it Y”) and substantial (not just snake food) real world result, evaluated at time of filing. C. Disclosure, §112: “The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is mostly nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.” (i) Enablement – Must enable a person of the ordinary skill and art to make and use the claimed invention without undue experimentation. Factors to consider include presence of working examples, prior art, relative skill of those in the art, breadth of claims. Incandescent Lamp: Patentees claimed all fibrous materials in their patent for filament light bulbs. Edison used bamboo and patentees claimed infringement. Claims need to be described/enabled: Patentees claimed fibrous material which includes all plants, but they only tested two – paper and wood – which had perpendicular fibers. Bamboo, which is a fibrous material (and so claimed) was quite different since it had parallel fibers. “If the patentees had discovered 3 fibrous and textile substances a quality common to them all .. as distinguishing them from other materials .. such claim might not be too broad.” Claims were not enabled – thus invalid, unenforceable. (ii) Description “The test for sufficiency of support is whether the disclosure of the application relied upon reasonably conveys to the artisan that the inventor had possession at that time of the later claimed subject matter.” Must “describe an invention and do so in sufficient detail that one skilled in the art can clearly conclude that the inventor invented the claimed invention.” Gentry Gallery v. Berkline Corp: Prior, reclining sofas had to be on the ends and facing different directions. This patent put reclining sofas next to each other on the same plane. This was done with a console between the recliners with controls on that console. Disclosure stated a fixed console with controls mounted to it. Claims are probably enabled because a reasonable person in the art could figure out where to put controls. But they were invalidated because the claims were broader than the disclosure – the disclosure clearly identifies the console as the only possible location for the controls. The invention had a limitation in the specification, not in the claims, but it was used to invalidate the claims. Finding limitations outside of the claims themselves was new territory. (iii) Disclosure also requires the inventor’s ‘best mode’ and the claims D. Novelty, §102(a): An invention must be new at the time claimed to be patentable. The invention cannot be known to the public, published, in public use within the US, or described in a pending patent application. This section reers to the time before the invention – it cannot be known/used within the US, or published/patented anywhere (ensure the US public is getting something new). (i) Anticipation Standard: Prior art must contain expressly or inherently each and every element of the claimed invention. The same information may be enough to invalidate a claim (anticipated) and also be inadequate to support claims. This is the same inquiry as infringement – a single prior art (or the infringing device) must include each claimed element. Rosarie v. National Lead Co: Patent was for a method of prospecting for oil based on composition of rocks nearby. NLC claimed they were not infringing because the patents were invalid, because they were not novel (known or used by others in this country). One Teplitz used this method when working for Gulf Oil, but Rosarie claims Teplitz 4 used this individually and did not disclose this information. Ct found the patents invalid – the method was used openly and in public on behalf of Gulf Oil, in the ordinary course of business, thus sufficiently open to the public to invalidate prior art. Teplitz did not actively keep it a secret. (ii) Priority: Typically, the first to reduce to practice or to conceive (first to make operating example, first to file enabling application/disclosure, full mental process of thinking through the invention/details) is the inventor (as opposed to first to file). Exception 1: If one conceives first and diligently reduces to practice; Exception 2: original inventor abandons/suppresses/conceals the invention. Griffith vs Kanamaru: Patent for compound used to treat diabetes. Griffith conceived of this in 1981, Kanamaru conceived of it and RTP in 1982. Griffith RTP in 1984, and thus most prove that the time from 1982 (just prior to Kanamaru’s conception) -1984 was reasonably diligent. Ct found this unreasonably diligent and awarded patent to Kanamaru. Griffith was waiting for a graduate student to become part of his team, and to secure outside funding. Ct did not want to make exceptions for university’s that would make the public to wait for the innovation. E. Non-Obviousness, §103: No patent if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to an ordinary person skilled in the art. Q of law, consider the scope/content of prior art, differences between prior art and invention, and level of ordinary skill in the art (also commercial success, unmet needs in the field, failure of other attempts). Graham v. John Deere Co: Patent was a plow shank that reduced vibration, difference was the hinge and how much of the shank moved when going over an uneven surface. Ct found this to be an obvious invention or change from the prior art. Post-1982 Act (creating the Federal Appellate Ct): Amplified the use of secondary sources and created scope of prior art. General Rule is it can be considered if it qualifies as prior art under 102 or if it is analogous art. [See slides] KSR v. Teleflex: Prior art included electronic throttle controls and adjustable pedals. Patent at issue combined these two things. Ct found this combination obvious. Strict application of the TSM Test (claim is obvious if the prior art, the problem’s nature, or the ordinary knowledge reveal some teaching, suggestion, or motivation to combine the prior arts). 5 F. Statutory Bars, §102(b): (i) Loss of Right: A person is entitled to a patent unless the invention was patented or described in a printed publication in any country or if in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of application. This section refers time before filing – cannot be in public use in the US, or patented/published anywhere (encourages early filing). In re Hall: Patent for something within a doctoral thesis that was printed in university’s publication. Issue was whether this was available. Feb 1979 filing date, so article must not have been available before Feb 1978. The publication was indexed in the university library in Germany. This prior art bars Hall’s patent issuance. Pretty light standard, was printed and available but not widely distributed/disseminated. Egbert v. Lippmann: Patent for a corset spring, applied for patent in 1866 (so critical period is 1865 by today’s law, 1864 at that time). Made the invention in 1855, “public use” is the bar at hand, was used by a single lady friend in this time period. The spring itself is unseen, hidden by fabric, but worn throughout that time and reused as the cloth wore out. There were a total of 3 individuals who knew about the spring, but its use need only be by 1 person if its use is not restricted, subject to secrecy, control. He needed to make her promise not to share the spring, even though she did not actually share it. City of Elizabeth v. Pavement Company: Patent was for a wooden roadway that had been used for 6 years on a busy toll-road in Boston. Ct does not invalidate this because the time period was considered experimental use – exerting control, limited to that one spot, only way for the inventor to test the merits. Inventor shows control and acts like it’s an experiment – checks up on it, limited use, etc. 2. Enforcement: A patent confers the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or imported the claimed invention for up to 20 years from the application FILING DATE (20 years - prosecution period). A. Claim Construction: Task of operationalizing the words of a claim – translating the words of a patent claim into a meaningful technological context for the purpose of determining validity and infringement. (i) Canons: Claims must be read in light of the specification, but limitations cannot be imported from the specification into the claims. Different claims have different meanings. Words presumed to have the same meaning across claims. Should be construed to preserve validity. 6 (ii) Interpretation: “Comprising” - indicates an open claim to anything possessing the claimed elements. “Consisting” – indicates a closed claim, limited to the specific elements only. (iii) Markman Hearings: Early in patent litigation intended to interpret the claims. Claim interp. is a question of law, can be reviewed de novo. Phillips v. AWH: Claim “Means disposed inside the shell for increasing its load bearing capacity comprising internal steel baffles extending inwardly from the steel shell walls.” Imported limitations from the specification – majority held that baffles must be at angles other than 90 degrees (benefit was deflection, 90 degree baffle was prior art). Dissent found no limitation. No hard rules for interpretation – can look at any outside source in any sequence, as long as those sources are not used to contradict claim meaning that is unambiguous in light of the intrinsic evidence. B. Infringement (i) Direct Infringement: Whoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the US or imports into the US any patented invention during the term of the patent therefor, infringes the patent. (ii) Literal Infringement: Allegedly infringing product falls within literal terms of the claims. (iii) Doctrine of Equivalents: The accused device or process must perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same result. Each element of a claim is material, and analysis must flow element by element to find equivalence. -> Prosecution History Estoppel: When an applicant makes an amendment that narrows a claim in order to satisfy any requirement of patentability, the patentee is presumed to have surrendered the scope between the amended version and the original claim. This is a rebuttable presumption. Festo v. Shoketsu: No hard rule for Prosecution History Estoppel barring a finding of equivalence, but in practice there is almost an absolute bar on arguing equivalence of amended elements – presumed surrendering; must look to reasons for the amendment in the file history. 7 (iv) Indirect Infringement: Aiding and abetting infringement by providing a non-staple article with infringing instructions or by entering a K which requires infringing performance (inducement). Selling/importing within the US a component of a patented device constituting a material part of its construction, that is not suitable for substantial non-infringing use (contribution). If no single entity performs all steps, then usually there is no infringement; but if there is a mastermind/controller over all entities involved, then that controller is an infringer (joint infringement). Requires knowledge/intent to be an infringer. CR Bard v. ACS: Patent was for method of using a catheter inserted into the coronary. Prior art covered insertions into the aorta. Doctors are the direct infringers but this action of indirect infringement (contributor/inducer) was against the suppliers. This catheter was capable of both aortic, catheter, or mixed and thus had non-infringing use. C. Limitations & Defenses (i) Disclosed but unclaimed subject matter: Johnson & Johnson v. RE Service: Patent used and claimed aluminum sheet but said other metals also work. If you disclose but do not claim, you cannot then go back and claim that disclosed material as an equivalent. That substitute is now given to the public. Alternative would be broad disclosures that are not reviewed by the PTO and then arguments that those disclosures are now claimed. (ii) Inequitable Conduct: Examines applicant’s behavior before the PTO, including misrepresentations, failure to disclose, submission of false info. Duty of candor and good-faith, and duty to disclose all known material information. Court balances materiality of omissions and the intent to deceive the PTO and can render the patent unenforceable. Kingsdown v. Hollister: Rather than appealing a rejection, a Kingsdown attorney saw a similar device made by Hollister (fair game to patent that and then sue for infringement right away if you have a priority date). Appeal was pulled back and a continuation was filed but the claim #s do not match up exactly (one set from one version, one set from an amended version) and they accidently included rejected claims in the amended version. PTO issued the patent and Kingsdown brought suit. Hollister discovered that the issued claims had already been rejected and claimed inequitable conduct. Kingsdown claimed it was a simple mistake missed the same way the PTO missed it. Ct accepts this based on several factors (similar language, same claim #50, long time period, etc). The Ct wanted a higher intent to deceive, gross negligence was not enough. 8 TheraSense held “specific intent, knew of reference, knew it was material, and made a deliberate decision to withhold it.” (iii) Exhaustion: An unconditional sale embodying the patented invention exhausts the patentee’s rights. Quanta Computers v. LG: LG licensed patents to Intel which authorized them to make and sell stuff embodying those patents. Agreement included a requirement that Intel tell customers not to use these patented products with non-Intel products. Quanta got LG chips from Intel, assembled a computer with non-Intel parts, and sold them. Court held that the LG-Intel agreement was not enforceable to Quanta. “The authorized sale of an article that substantially embodies a patent exhausts the patent holders rights and prevents the patent holder from invoking patent law to control post-sale use of the article. LG licensed those patents. Intel’s stuff substantially embodies the patents because they had no reasonable non-infringing use and included all the inventive aspects of the patented methods. Nothing in the agreement limited Intel’s ability to sell its products practicing the LGE patents.” (iv): Experimental use: (a) Common Law: Amusement, curiosity, philosophical. (b) Experiment for regulatory submission: Related to the development and submission of info to the FDA. Madey v. Duke: Madey had patent in a lab at Duke but left after fallout. Duke continued to use the patent in the lab, and Madey sued. Duke claimed non-profit research, but the court found that it was connected to their legitimate business purposes. Not experimental because its use was not solely for amusement, to satisfy idle curiosity, or for strictly philosophical inquiry. Merck v. Integra: Integra was using the patent not to make generics, but for additional upstream research. Ct said the statute extends this far – “for experimentation on the road for regulatory approval. Drug maker had a reasonable basis for believing the compound may work, through a particular bio process, to produce a particular effect, and uses the compound in research that, if successful, would be appropriate to include in a submission to the FDA. That use is reasonably related to the development and submission of information under federal law.” 9 (v): Patent misuse: A misused patent cannot be enforced. Motion Picture Patents v. Universal Film: MP had a patented film player and their licenses included a restriction that required purchasers to also purchase film of MP (“tie in”). Patent was unenforceable due to misuse (though getting out of the arrangement could be a cure). -> In Morton Salt v. GS, Morton Salt sold patented machines tied to purchases of unpatented salt tablets, same result. For many years, these tie-in misuses were per se unenforceable. But this has shifted §271(d) – still misuse if patentee has market power (price setter) in the patented product; overlap with antitrust laws. D. Remedies (i) Judgments: A patent is typically enforceable from the date of issuance to the date of expiration. Reasonable royalties can also be awarded for use between publication and issuance. Preliminary injunctions are common before a judgment. Injunctions are the common judgment, with damages (compulsory licenses) the exception. (ii) Damages: Usually argued by economists and experts regarding lost profits. Award is never less than a reasonable royalty, but can be increased 3x for willful infringement or exception cases, along with fees/costs. -> Lost profits OR reasonable royalty is the norm. Ebay v. MercExchange: Factors to determine injunction – (1) irreparable harm – presumed by infringement and non-invalidity claims, (2) damages inadequate – damages are usually inadequate to remedy a continuing interference, (3) balance of the hardships between P and D – usually favors the patentee, (4) public interest – with exception for important public needs, public interest favors protecting incentive structure of patent system. Evolved into general rule that injunctions should normally issue except in instances implicating important issues of public health, safety, and welfare. But Court said this is no longer accurate – it must conform to traditional principles of equity. Trial judges must work through the factors and use discretion. 10 II. TRADE SECRETS 1. Elements (UTSA, Common Law, Restatements) A. Trade secret, components: (i) Information – method, process, formula, etc. (ii) Derives value from its secrecy: Value indicated by changes in market share, other’s failures, input/r&d into the trade secret, others were paying for that information, hiring of employees by competitor, someone broke into the building (risk) for the secret. Does not need to be an absolute/perfect secret - can be known in one industry but not in another and still be a trade secret in the latter. (iii) Subject to reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy: Includes confidentiality agreements, legends indicating proprietary information, building security/personnel, limiting access, criminal background checks on employees. Balancing reasonable efforts (costs) vs the value of the trade secret. Public disclosure of at trade secret destroys its legal protection as a trade secret. If the gov’t/3rd P publishes it, if it’s easily reverse-engineered, or if by some other mechanism it reaches the general public. Metallurgical v. Fourtek: Trade secret was a zinc recovery process through modified furnaces. Upon delivery of the furnaces, P reworked them for better results (twice). Ds provided furnaces to P but after bankruptcy, created Fourtek. As Fourtek, they manufactured this modified furnace for a competitor of P. Court said that the specifics were not a secret but the combination of modifications was. Further, secrets need not be absolute; these were disclosed to further business interests with partners. These are all factors but there is no bright-line rule; very fact-intensive. Rockwell v. DEV: Rockwell makes drawings that have the details of manufacturing. Two workers of Rockwell (1 caught taking the drawings) left for competitor DEV. DEV argues that Rockwell did not keep them a secret – that these are floating around the manufacturing and bidding companies, so it does not matter how DEV acquired them. Rockwell restricted access, permitted copies but required them to be destroyed, and drawings gave notice of proprietary information, etc. Ct said “reasonableness” cannot be determined on MSJ. 11 B. Misappropriation – improper means or breach of confidence (i) Acquisition of a TS of another by a person who knows or has reason to know that the TS was acquired by improper means. EI DuPont v. Rolfe Christophers: DuPont was having a methanol plant constructed. Third party hired photographers to fly above the plant and photograph the plant. Ds argued that photographing the ground was not illegal or improper. Ct held it was improper – photographing proprietary information is not ethical. To expect P to cover the plant during construction is unreasonable. Circumventing reasonable security precautions is misappropriation. You have to do your own effort or reverse engineer it, otherwise its improper. (ii) Or, disclosure/use of TS of another without express or implied consent by a person who: (a) used improper means to acquire the TS, or (b) at the time of disclosure/use, knew or had reason to know that his knowledge of the TS was, (1) derived from one who utilized improper means, (2) acquired under circumstances giving rise to a duty to maintain its secrecy, or (3) derived from a person who owed a duty to the holder of the TS, or (c) before a material change in position, knew or had reason to know that it was a TS and that knowledge of it had been acquired by accident/mistake. Smith v. Dravo Corp: Smith invents container boxes and dies, heir needs to sell the business to pay inheritance tax. In the business meetings, they disclosed details of the business. Potential buyer ultimately backs out of the purchase, but engages in the business and ultimately ruins the original company, in reliance on those trade secrets. This was not misappropriation – they did not acquire the secrets improperly – but what they did with them was an improper breach of conf. 2. Other TS Stuff A. Proper Means: Independent invention, reverse-engineering, public observ. Kadant v. Seely: Technology for papermaking. Corlew worked for Kadant and then ultimately ended up working for Seely after working intimately with Kadant’s details. Seely then manufactured similar parts, and Kadant claimed they had obtained these secrets improperly, demanding a preliminary injunction. Seely claimed that 12 they reverse-engineered the product after legally obtaining them on the market. Kadant argued this would have taken 1.7 years, but did not meet their burden of proof because this was the material issue. Whether he took it or not is not dispositive (could have taken but not shared, or didn’t take but still knew the info and shared it). B. Departing Employees: Balancing employee mobility and protection of TS (i) Default rules of employee-inventions, may be modified by K: Hired to invent - the invention belongs to the employer Invented using employer’s resources – invention is the employee’s but employer get’s “shop rights” or non-exclusive license to use it Employee invents on own – employee owns the invention (ii) Noncompetition Agreements are generally enforceable IF: of reasonable length and reasonable to protect an employers legit interest, of reasonable scope and not unduly oppressive, and reasonable from public policy standpoint. (CA is stricter) Edwards v. Arthur Andersen: Employer worked for Andersen and signed noncompetition agreement. Andersen was taken over by HSBC and required to sign a new Termination of Noncompetition Agreement (that included a release of all claims, preserve confidential info indefinitely, etc). He refused to, and they let him go, and he brought suit claiming the original noncompete is unenforceable. Ct held it was unenforceable. Ct balances “restrained” vs “prohibited.” Andersen argued the statute “restraint” meant “prohibiting” which the K was not, Edwards argued “restraint” meant “limiting” which the K surely was. Ct agrees with Edwards. (iii) Licensing: Warner-Lambert v. Reynolds: P had license to make Listerine with Reynolds’ secret formula. They signed K for licensing fee that was indefinite as long as Lambert sold the product. The formula was disclosed and became public knowledge, so Lambert argued they should no longer need to pay the license. Ct disagreed, if they wanted to make the license contingent on secrecy they could have done that. (iv) Defenses: Not a TS, any proper means, etc. (v) Remedies: Because of tort/property flavors, a lot of remedies are available including money damages. Injunctions are available against use until it becomes public, ordering the return of 13 information/documents, etc. Damages include any damages caused, actual losses and lost profits. Extra damages for willful and malicious behavior and fees. III. COPYRIGHT 1. Big Picture (i) Term: Life of author + 70 years; 95 years for publications, 120 years for institutional/hired work. (ii) Rights: To make copies/reproduce, prepare derivative works, control distribution copies (first sale), control public performance, and to display publicly. -> Termination: Except for works-for-hire, original authors have an inalienable right to terminate licensing agreements 35 years later (within 5 year window) (iii) Formalities: Notice ©, publication, registration, and deposit. These requirements have loosened over time but registration is necessary for an infringement action. 2. Copyrightable Subject Matter, §102(a) (i) Original works of authorship fixed n any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device. Includes: literary works, musical works including accompanying words, dramatic works including any accompanying music, choreography, pictorial/graphic/sculptural works, motion picture and other audiovisual works, sound recordings, and architecture. Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service: [Fact/expression dichotomy.] Creative work was the white pages of a phone, in alphabetical order. Rural is a public utility with access to the data and compiled it for their counties. Feist copied their data as part of a larger compilation. (1) Facts are not copyrightable, they are not original to the author, but (2) compilations of facts generally are. To be original, it must be an independent creation with some modicum of creativity. Rural had no expressive or unique input in their compilation – alphabetical order is standard, and they were required to produce it by state regulations. To be copyrightable compilations, they must be selected, coordinated, and arranged with a minimal 14 degree of originality. The facts remain uncopyrightable, but the compilation can be (narrow/thin protection). Baker v. Seldon: [Idea/expression dichotomy.] Ideas are generally not protectable by copyright – go to the patent system. Copyright covers only the expressive aspects, not the utilitarian aspects. Selden’s books were about a peculiar system of bookkeeping. Baker used these theories with slight modifications, and created his own for resale – both made money by selling their forms. Practicing the methods laid out in Selden’s book does not amount to infringement? Otherwise would be a fraud and surprise upon the public – there is no inquiry into novelty/nonobviousness as in the patent world. The material claimed by the copyright may not be new, or even thought of by Selden. If you want to practice this form of bookkeeping, you would need these. Morrissey v. P&G: The claimed copyrighted material were rules for a sweepstake. Court denied any copyright protection - when the subject matter is very narrow so that only a few modifications can exhaust all possible future forms, then the subject cannot be copyrightable. If there are only a few ways to express the subject matter, then the subject cannot be exhausted by copyright. Merger or idea/expression inseparability - “Where there is only a one or but a few ways of expressing an idea, courts may find that the idea behind the work merges with its expression with the result that the work is not copyrightable.” Lotus v. Borland: Lotus claimed the command menu hierarchy (type Quit to make it quit). Court said this material is not copyrightable because it’s a method of operation (of the spreadsheet). There is protectable subject matter in graphical user interfaces, and the code itself is copyrightable (thin). Brandir Int’l v. Cascade Pacific Lumber: [Conceptual separability.] Levin was playing with wire designs and a friend encouraged him to make a ribbon bike rack. Levin’s copyright registration was denied but he brought suit anyway after CPL made the same thing. Ct found the bike racks not copyrightable because it was a useful article – though it may have an expressive feature, they are not separable from the utilitarian function of the article. “If design elements reflect a merger of aesthetic and functional considerations, the artistic aspects of a work cannot be said to be conceptually separable from the utilitarian elements.” The dissent wanted to apply the reasonable person’s standard, “the relevant question is whether the article causes an ordinary reasonable observer to perceive an aesthetic concept not related to the article’s use.” 15 3. Ownership (i) Generally, the creator is the owner unless the subject matter is a work for hire (employee or enumerated category + K). Then, the employer is considered the author. Co-owners are cotenants. (ii) Work can be made-for-hire if (1) the creator is an employee within the scope of their duties, or (2) the work is specially commissioned and a K expressly provides that it will be workfor-hire and a contribution to a collection, part of a motion picture, or a translation. CCNV v. Reid: CCNV wanted a Xmas display and hired Reid to make it. CCNV came up with the image and price point, and found Reid to put it together. Most of the details came from CCNV, the labor and execution came from Reid; split input of details/expression. After the display, Reid repaired it, and refused to return it, claiming copyright ownership of it. Case turned on interpretation of “employee” within the §. Court looks at multiple factors (p.493 – skills, ownership of tools, location, discretion, payment, benefits, etc)) from agency law and found that he was not an employee, but an independent contractor. CCNV conceded it did not fit within part 2 of §. Court said it may be joint-work, though. Aalmuhammed v. Lee: WB hired Lee to make Malcolm X. Washington was lead actor and asked A to help him. A ultimately consulted with the movie makers – helped make it authentic by rearranging the prayers, rewrote scenes with new characters, did some voice over, and helped get them into filming sites. The movie credited him as a Tech Consultant, and he was denied co-author title. He filed for copyright – they granted him but they told him its in conflict with other claims (by WB). If he is a co-author with WB, he would be entitled to 50% of the profits (Lee signed work-for-hire agreement under part 2 of §101. The § also says “joint work is a work prepared by two or more authors with the intention that their contribution be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.” It was clearly copyrightable work, they clearly intended it to be merged into the final product – so case hinged on “two or more authors with the intent..” Court looked at the degree of control and whether they held themselves out as co-authors, looking at objective indications. They find that he is not an author. 16 4. Infringement (i) Direct Infringement: copying + improper appropriation Arnstein v. Porter: Arnstein recorded some songs that made it into circulation, claimed that Porter infringed those songs with records of his own. First element – copying: Arnstein argues that Porter had access to the recordings in circulation (radio) or could have hired someone to ransack his apartment. Circumstantial evidence can include striking similarities, the same minor flaws, etc and also requires access (independent creation is okay). This element can be satisfied with identical reproduction, or access + substantial similarities. Nichols v. Universal Pictures: Nichols made a play and claimed that UP infringed when they made another play. Court assumed that there was copying to analyze the next element, improper appropriation. So, copying IS OKAY sometimes as long as it is not improperly appropriated. Requires comparison between the copyrightable components of one piece and the specifics of the alleged infringer. Determine the protectable expressions – themes, characters, if they are well developed. The more general, the less copyrightable, or else the copyright extends to “ideas” which are not protected. Harder when abstract parts are taken out rather than a block of the material. Fact-specific, the boundary is different for every case – but here, there is no infringement. Characters and theme were either too general or too different. Use levels of abstraction to determine the copyrightable elements. Are the protected aspects subs. similar to a lay person? Computer Assocs Int’l v. Altai: CA’s software program ADAPTER was copied by Altai’s program OSCAR 3.4. Altai rewrote the code in v3.5 and CA argues they are substantially similar and still infringe even if not literally copied anymore. New structural analysis for software copyright: Abstraction, filtration, and comparison. Abstraction starts with the code or portions thereof, looking at levels of abstraction to the function it performs. Small bits of code may be copyrightable, the whole idea cannot be – fact specific. Each subpart is then analyzed and the copyrightable parts are pulled out, leaving behind anything that is not – public domain information, elements dictated by efficiency or external factors (which are not coded as expression). We hope to be left with golden nuggets of protectable expression. The final part is a comparison between the nuggets and the alleged infringer – weak copyright protection for software. Anderson v. Stallone: Stallone said he was thinking about a Rocky IV. Anderson then wrote a script/idea for the movie and pitched it to 17 Stallone and MGM. After the movie’s release, which included some elements from Anderson’s treatment but also some of the ideas that Stallone originally mentioned, Anderson sued Stallone for infringement. Court found that instead, Anderson infringed Stallone’s Rocky series. Copyright includes a right to make derivative works – and here, Anderson used the same characters, relationships, and stories. Since Anderson’s work is an unauthorized derivative work, no part of the treatment can be granted copyright protection. Anderson argued that his non-infringing parts should be granted copyright, but the court denied this because there is no new protectable expression, relying on Stallone’s copyrights. (ii) Indirect Infringement: A direct infringer + Agency (master/servant), Vicarious (supervision + financial interest), OR a contributor (induced/encouraged) Exception: substantial non-infringing use Sony v. Universal Studios: Movie-makers suing the maker of VCRs as a contributory infringer because users of the VCRs infringe copyrights by copying recorded shows. Court did not adopt Universal’s theory of contributory infringement, because there were significant noninfringing uses, and Sony did not encourage/induce the infringement. MGM Studios v. Grokster: Grokster had software like Napster, which allowed p2p file sharing of copyrighted material. Grokster argues they are not contributory infringers because there are potential noninfringing uses (10%+) per Sony case. However, Grokster advertised their services as a replacement to Napster, and promoted its infringing-capabilities. “One who distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright as shown by clear expression or other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement, is liable for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties.” Evidence of intent to induce infringement – links to Napster, executive statements, advertising/business model, etc. “Mere knowledge of potential CPR infringement or of actual infringing uses is not enough to subject a distributor of a product to liability. The inducement rule, instead, premises liability on purposeful, culpable expression and conduct, and thus does nothing to compromise legit commerce or discourage innovation having a lawful promise.” 5. Defenses (i) Independent creation, consent/license, inequitable conduct, copyright misuse, 1st Amendment, Immoral/illegal/obscene works, and SoL (3 years from claim). 18 - (ii) Fair Use, §107: Excuses unauthorized appropriation when it advances public benefit without substantially impairing the economic value of the first work. Purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Analysis: Purpose and character of use – commercial, transformative? Nature of CPR work – published, facts, or ideas? Amount/substantiality used – what/how much is taken? Market effects – derivative markets, displacement? Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises: Harper held copyright to manuscripts of President Ford. Time was going to buy these manuscripts for publication. But before that, Nation obtained these memoirs and published them in their own media outlet. Time subsequently rescinded their offer to purchase the copyright license because the material had already been published. Harper brought suit and Nation claimed fair use. Purpose and use – commercially motivated, trying to beat the release of unpublished work, bad-faith obtainment of the material, desire to use the expressive nature rather than just facts, etc. Nature of the work – unpublished (weighs against fair use), mix of facts and expression. Amount used – small % but stole the heart of the manuscripts. Effect of use on market – Time decided not to license the work because Nation had already published it. article could have superseded the purchase of the book. Court found this was not fair use. American Geophysical Union v. Texaco: Texaco’s scientists would photocopy scientific journals for their use. Scientist had 8 copied articles – 3 of which he looked at, 5 he did not – copied for later use/reference and convenience. Purpose and use – personal convenience, less bulky, no damage to original, prevent purchase of multiple copies by Texaco (last one overcomes the others against Texaco). Nature of the work – education/research, tilts towards Texaco. Amount used – all of it. Effect of the use – lack of subscriptions, licensing agreements, back-issues, etc. Not fair use. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music: Acuff sued Campbell for parodying their song. Parodies are socially beneficial but they are going to inevitably infringe copyrighted material. Purpose/use – commercial. Nature of work – original works of parodies is always going to be expressive/artistic/published work. Use – needs to use enough of original to be recognizable. Effect of market – unchanged, two separate markets. Court remanded for evidence on market effects. 19 Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley: DK published a 480page coffee table book of the Grateful Dead (timeline) and used 7 pictures owned by BGA, that were once concert posters. Court found fair use based on the method of use – they were smaller, used in a timeline rather than for their expressive promotional value. Court found no “derivative market for these pictures in coffee table books” even though they may now exist. Commercial use, but not dispositive. Insubstantial portion of the book. Court found fair use. Blanch v. Koons: Blanch took photograph for magazine that showed woman’s legs. Koons took the legs, changed background, changed lighting, changed angle, took out the original/unique/expressive components, etc. He was trying to express the materialism of our society. Court found fair use – very transformative, but did take substantial amount of the work. Nature of the work was a photo, typically deserving of protection. 6. Remedies (i) Injunctions (temporary or permanent) may be granted (ii) Damages (actual, infringer’s profits, statutory) also available (iii) Impounding/destruction the infringing material is an option (iv) Fees may be awarded (v) Criminal offenses exist but are unusual IV. TRADEMARK 1. Definitions & Misc, 15 USC § 1127 (i) Trademark: any word, name, symbol, or device or any combination thereof, used by a person or which a person has a bonafied intention to use in commerce. Used to identify and distinguish goods from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate their source even if unknown. (ii) Service mark: Same, except used to distinguish the services of one person from services of another. Titles, character names, and other distinctive features of radio or TV programs may be registered as service marks. (iii) Certification mark: Same, except permits a person other than the owner to use a registered mark indicating/certifying regional or other origin (CE), material, manufacture (organic), quality, accuracy, or other characteristics. 20 (iv) Collective mark: Trademark/service mark used by members of a cooperative organization. (v) Trade dress: Refers to the design or packaging of materials even of the product itself, that serve the same source-identifying functions as trademarks. (vi): Protection of unregistered marks depends on use in commerce (where, when). Registered marks are given nationwide protection. Registration will be denied if it consists of immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter, or flags or national symbols, or falsely suggests connections. 2. Trademark Subject Matter Qualitex Co v. Jacobson Products: Qualitex used a unique green-gold color for their dry cleaning press-pads. Jacobsen then entered the market with the same color, so Q brought suit. Issue was whether a color could be trademarked. Ct found the statutory language very broad with no limitation, finding no reason to exclude colors if they fit within the general principles. Turning the “functionality doctrine,” which prevents trademarking of a functional aspect of the product itself (like copyright law). The color was not a functional feature of the pads – it was not essential to the use/purpose/cost/quality of the article and its protection does not put competitors at nonreputational-related disadvantage. 3. Establishing Rights (i) Generally: Generic terms are never protected Descriptive terms are protected IF there is secondary meaning (primary significance is not with the description but with the producer; look at advertising, sales, use) Suggestive and arbitrary/fanciful terms are protected Zatarains v. Oak Grove Smokehouse: Zatarains tried to trademark “Fish-Fri” and “Chick-Fri.” Oak Grove used “Fish Fry” and “Chicken Fry.” Court found it was either generic or used as an event getting together to fry fish. Court applied different tests – resort to a dictionary (findings above), imagination (is any required to conclude the nature of the goods? If so, suggestive), and “whether competitors would be likely to need the terms used in the TM to describe their products.” Court decided CHICK FRI was descriptive with no secondary meaning and thus not protected. FISH FRI was a descriptive mark with secondary meaning in the LA area. They 21 demonstrated this secondary meaning with surveys and sales/advertising data. However, Oak Grove applied the “Fair Use Defense” – “when the term is used fairly and in good faith only to describe to users the goods or services, … only allowed for descriptive terms and when used in a descriptive rather than TM sense.” Two Pesos v. Taco Cabana: Taco Cabanas had a unique ambiance in their restaurants that Two Pesos replicated. Court found this an inherently distinctive but not descriptive design, with no secondary meaning. Court had to decide whether or not trade dress needs a secondary meaning. Court holds that no secondary meaning is required when trade dress is inherently distinctive. Wal-Mart v. Samara Bros: Samara Bros had uniquely designed children’s clothing that was sold to retailers under K. Wal-Mart then hired a manufacturer to copy them exactly and then sold them through their outlets. Samara Bros brought trade dress infringement suit. Issue was whether design is inherently distinctive (and if so, no need to show secondary meaning per Two Pesos; if not, then must show secondary meaning per Zatarains). Court said it does need a secondary meaning, that design isn’t inherently distinctive (like color). Park N Fly v. Dollar Park And Fly: PNF sues DPAF for infringement. PNF had become incontestable (time) so DPAF cannot argue it’s merely descriptive. Court thus enforced it. Dissent argued it was an error to issue the TM and that it never had secondary meaning which is required of descriptive TMs so nonsensical to prevent that point from being argued. 4. Infringement (i) A plaintiff must establish (1) it has a valid mark entitled to protection, (2) D used that mark (3) in commerce, (4) “in connection with the sale or advertising of goods/services,” (5) without P’s consent., and (6), P must show that D’s use is likely to cause confusion as to the affiliation, connection, or association of D with P, or as to origin, sponsorship, or approval of the D’s goods, services, or comm. activities by P. [Use] Rescuecom v. Google: Google offers advertising based on searching – one can purchase search terms for their own mark or competitors or descriptions. Once those terms are searched, your advertisement appears on the same page as suggested results – at the top and side of the page. Rescuecom argues that other logos are displayed when consumers search for their site. Court found that this was use – but remanded to determine confusion for liability. 22 [Confusion] AMF v. Sleekcraft: AMF builds Slickcrafts, years later Nescher comes out with Sleekcraft boats. Is D’s use likely to cause confusion/mistake/deceive? 8 factors – strength of mark, proximity of goods, similarity of marks, evidence of actual confusion, marketing channels used, degree of care likely to be applied by purchaser, Ds intent in selecting the mark, and likelihood of expansion of product lines. There are different types of confusion: initial interest, implied endorsement (sponsorship), post-sale, reverse (the infringer is the original), conventional (source). (ii) Dilution by blurring/tarnishing Louis Vuitton v. Haute Diggity: LV brought suit against HD for their dog toy “Chewy Vuitton.” LV must show – famous distinction mark, d used it, similarity evokes association, and the main part – that the association is likely to impair the distinctiveness of the famous mark or likely to harm the reputation of the famous mark. 6 factors: similarity between marks, inherent distinctiveness, if famous mark is engaging in substantially exclusive use of the mark, recognition, intended association, actual association. No dilution found. 5. Defenses (i) Fair use, genericide (term has become common for describing type of product), functionality, abandonment (discontinued use with intent not to resume). Murphy Bed Door Co v. Interior Sleep Systems “A term or phrase is generic when it is commonly used to depict a genus or type of product, rather than a particular product.” TrafFix Devices v. Marketing Displays: TD had double-spring mechanism to keep signs upright in bad weather and claimed that their double spring feature was an identifying feature of their trade dress. Court determined that the past patent protection suggested that the feature was functional – it was a specification protected by the patent system. It cannot be protected by trademark separately because that would extend the monopoly. MLB v. Denarious: Brooklyn Dodgers moved to LA and Ds made restaurant in NY called “The Brooklyn Dodger.” D argued abandonment, “if its use has been discontinued with intent not to resume.” Court found that the logo had been abandoned.

![Introduction [max 1 pg]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007168054_1-d63441680c3a2b0b41ae7f89ed2aefb8-300x300.png)