Performing Patriarchy in Macbeth

advertisement

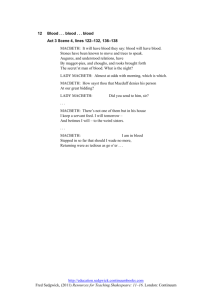

Men Behaving Madly Performativity and Patriarchy in Macbeth Good and Evil in Doctor Faustus FAUSTUS. Ah, Faustus, Now hast thou but one bare hour to live, And then thou must be dammed perpetually. Stand still, you ever-moving spheres of heaven, That time may cease, and midnight never come! [...] The stars move still; time runs; the clock will strike; The devil will come, and Faustus must be damned. O, I’ll leap up to my God! Who pulls me down? See, see, where Christ’s blood streams in the firmament! One drop would save my soul, half a drop. Ah, my Christ! Ah, rend not my heart for naming of my Christ! Yet will I call on him. O, spare me, Lucifer! Where is it now? ’Tis gone; and see where God Stretcheth out his arm and bends his ireful brows! [...] My God, my God, look not so fierce on me! Adders and serpents, let me breathe a while! Ugly hell, gape not. Come not, Lucifer! I'll burn my books. Ah, Mephistophiles! (A-text, 5.2.57-115) Good and Evil in Doctor Faustus E. K. Chambers cites a number of accounts of ‘one devil too many’ appearing in Elizabethan performances of Doctor Faustus. An example: ‘Certaine Players at Exeter, acting upon the stage the tragical storie of Dr. Faustus the Conjurer; as a certaine number of Devels kept everie one his circle there, and as Faustus was busie in his magicall invocations, on a sudden they were all dasht, every one harkning other in the eare, for they were all perswaded, there was one devell too many amongst them; and so after a little pause desired the people to pardon them, they could go no further with this matter; the people also understanding the thing as it was, every man hastened to be first out of dores.’ (Chambers 1923: 423-24) Andrew Sofer argues that ‘much of the fascination conjuring held for Elizabethan audiences can be traced to its unnerving performative potential’, reading even Faustus’s self-address as ‘a magical mode of self-fashioning’ in which ‘Faustus conjures himself into being through actions made material by words alone’ (2009: 2, 18). Macbeth and evil Many critics have seen Macbeth as a play about the nature of ‘evil’. In 1959, for example, Irving Ribner argued that: ‘Macbeth is in many ways Shakespeare’s maturest and most daring experiment in tragedy, for in this play he set himself to describe the operation of evil in all its manifestations: to define its very nature, to depict its seduction of man, and to show its effect upon all of the planes of creation once it has been unleashed by one man’s sinful moral choice.’ (1959: 147) Macbeth, dir. Rupert Goold, 2010 Goold’s film ends with Macbeth and Lady Macbeth descending into hell. Is a belief in the supernatural necessary in order to appreciate the play? Macbeth and evil MACBETH. Two truths are told, As happy prologues to the swelling act Of the imperial theme. - I thank you, gentlemen. – This supernatural soliciting Cannot be ill, cannot be good. If ill, Why hath it given me earnest of success, Commencing in a truth? I am Thane of Cawdor. If good, why do I yield to that suggestion Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair And make my seated heart knock at my ribs Against the use of nature? Present fears Are less than horrible imaginings. My thought, whose murder yet is but fantastical, Shakes so my single state of man that function Is smothered in surmise, and nothing is But what is not. BANQUO. Look how our partner’s rapt. MACBETH. If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me Without my stir. (1.3.126-43 An evil play? The Macbeth myth: Charles Macklin’s production, 1772 – audience riots (due in part to rivalry with Garrick). New York, 1849: Englishman William Charles Macready and American Edwin Forrest play in rival productions. Riots involved an estimated 20,000 people, and resulted in 30 fatalities and many more injuries. When Constantin Stanislavski mounted a production at the Moscow Art Theatre, his prompter was found dead during a performance. Bad luck surrounded Laurence Olivier’s 1937 production at the Old Vic (not least the death of actress Lilian Baylis, due to play Lady Macbeth). Actor Harold Norman, playing Macbeth, was stabbed to death for real at the Oldham Rep in 1947. (Dickson 2009: 217) Of course, there are rational explanations for the ‘curse’. Staging the unspeakable When the witches claim to perform ‘a deed without a name’ (4.1.65), they unsettle our faith in the possibility of explaining and articulating the unknown. This sense that the most terrifying aspects of existence transcend language manifests itself throughout the play: ‘Speak, if you can. What are you?’ (Macbeth, 1.3.45) ‘Stay, you imperfect speakers, tell me more. … Speak, I charge you.’ (Macbeth, 1.3.68,76) ‘O horror, horror, horror! Tongue nor heart cannot conceive nor name thee.’ (Macduff, 2.3.62-3) ‘…I have words That would be howled out in the desert air Where hearing should not latch them.’ (Ross, 4.3.194-6) ‘…the grief that does not speak Whispers the o’erfraught heart and bids it break.’ (Malcolm, 4.3.21011) Inverted prayer To an audience with faith in the power of words to solicit the supernatural (for good or for evil), the language of the play is highly-charged: LADY MACBETH. …Come, you spirits That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full Of direst cruelty. … Come to my woman’s breasts, And take my milk for gall, you murd’ring ministers, Wherever in your sightless substances You wait on nature’s mischief. (1.5.39-49) Inverted prayer As he contemplates his future crimes, Macbeth’s couplets tend to foreground the play’s cosmology of heaven and hell, as well as taking on the form of inverted prayer: Stars, hide your fires, Let not light see my black and deep desires. (1.4.50-1) I go, and it is done. The bell invites me. Hear it not, Duncan; for it is a knell That summons thee to heaven or to hell. (2.1.62-4) It is concluded. Banquo, thy soul’s flight, If it find heaven, must find it out to-night. (3.1.142-3) Inverted prayer It is perhaps this perversion of religious speech which renders Macbeth unable to recourse to prayer: MACBETH. …I could not say ‘Amen’ When they did say ‘God bless us.’ …I had most need of blessing, and ‘Amen’ Stuck in my throat. (2.2.26-31) Inverted prayer Macbeth echoes his wife’s inverted prayer later in the play: MACBETH. …Come, seeling night, Scarf up the tender eye of pitiful day, And with thy bloody and invisible hand Cancel and tear to pieces that great bond Which keeps me pale. (3.2.47-51) Witches Of course, the most famous uses of inverted prayer in the play are in the witches’ incantations: Fair is foul, and foul is fair, Hover through the fog and filthy air. (1.1.10-11) Double, double, toil and trouble, Fire burn, and cauldron bubble. (4.1.21-1) Their power to command forces beyond human comprehension is a key aspect of the play’s mythology. The next clip is from Orson Welles’ Macbeth (1948). Witches Are the witches human or inhuman? On the one hand, there is something of the ‘village witch’ about their petty concerns in 1.3 (the first witch’s vendetta against a mean-spirited sailor’s wife, for example). On the other, Banquo suggests that they ‘look not like th’ inhabitants o’ th’ earth’ (1.3.39) and that ‘The earth hath bubbles, as the water has, / And these are of them’ (1.3.77-8). Do the witches control, or merely foresee, the future? In other words: is Macbeth responsible for his actions, or merely a puppet of destiny? Shakespeare’s source, Holinshed’s Chronicles, is also ambiguous: ‘…the common opinion was, that these women were either the weird sisters, that is (as ye would say) the goddesses of destiny, or else some nymphs or fairies, endued with knowledge of prophecy by their necromantical science, because everything came to pass as they had spoken.’ The politics of Macbeth One can read Macbeth as an intensely conservative political drama: Performed only months after the 1605 Gunpowder Plot, it demonstrates the terrible consequences of regicide; It serves to legitimate James’s authority by presenting his rule as supernaturally-foretold: Banquo was his ancestor, and the procession of ‘eight Kings’ in 4.1 illustrates his royal lineage (conveniently omitting his politically-awkward mother, Mary Queen of Scots). The divinely-appointed King’s ability to heal scrofula with ‘holy prayers’ is narrated in a (completely unnecessary) passage in Act 4 (4.3.141-60). James is known to have participated in such ceremonies himself. See the opening sequence of Trevor Nunn’s Macbeth (1978)… Mythologising ‘evil’ MACBETH. …Besides, this Duncan Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been So clear in his great office, that his virtues Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued against The deep damnation of his taking-off. (1.7.16-20) OLD MAN. ’Tis unnatural, Even like the deed that’s done. On Tuesday last A falcon, tow’ring in her pride of place, Was by a mousing owl hawked at and killed. (2.4.10-13) DOCTOR. Foul whisp’rings are abroad. Unnatural deeds Do breed unnatural troubles. (5.1.68-9) Association of witches with natural disorder: thunder, lightning, fog, filthy air. Mythologising ‘evil’ Clergyman Robert Bolton, preaching in 1621: ‘Take sovereignty from the face of the earth, and you turn it into a cockpit. Men would become cut-throats and cannibals one unto another. Murder, adulteries, incests, rapes, robberies, perjuries, witchcrafts, blasphemies, all kinds of villainies, outrages, and savage cruelty, would overflow all countries. We should have a very hell upon earth, and the face of it covered with blood, as it was once with water.’ James I’s ideology of Absolutism, says Alan Sinfield, ‘…represented the English state as a pyramid, any disturbance of which would produce general disaster. … This system was said to be “natural” and ordained by “God”; it was “good,” and disruptions of it were “evil.”’ (1992: 96) Legitimate violence ‘It is often said that Macbeth is about “evil”, but we might draw a more careful distinction: between the violence which the State considers legitimate and that which it does not.’ (Sinfield 1992: 95) CAPTAIN. …brave Macbeth – well he deserves that name! – Disdaining fortune, with his brandished steel Which smoked with bloody execution, Like valour’s minion Carved out his passage till he faced the slave, Which ne’er shook hands nor bade farewell to him Till he unseamed him from the nave to th’ chops, And fixed his head upon our battlements. DUNCAN. O valiant cousin, worthy gentleman! (1.2.16-24) Legitimate violence Macbeth’s illegitimate violence is punished, finally, by another embodiment of the legitimate order of violence from which he transgressed – the severing of his own head by Macduff. But is the ‘illegitimate’ violence in this play just an extension of the logic of ‘legitimate’ violence? Final parallel between Duncan/Macbeth and Malcolm/Macduff… Note Macduff ’s willingness to legitimate Malcolm’s (feigned) ‘black and deep desires’ in Act 4 (‘take upon you what is yours’; 4.3.71). Gender and performativity For Judith Butler, gender identities are ‘a kind of impersonation and approximation… a kind of imitation for which there is no original’ (Inside/Out, 1992). ‘It’s a boy!’ may be a statement of biological fact, but it is also a ‘performative utterance’ – the first in a long series of repetitions of gender norms which ‘create’ the male. Policing masculinity Lady Macbeth assumes a dominant role in policing her husband’s masculinity: ‘When you durst do it, then you were a man’ (1.7.49) ‘Are you a man?’ (3.4.57) ‘What, quite unmanned in folly?’ (3.4.72) Macbeth recognises her masculinity when he tells her, ‘thy undaunted mettle should compose / Nothing but males’ (1.7.73-4). Lady Macbeth Lisa Jardine analyses Lady Macbeth in light of Hic Mulier: or the Man-Woman (1620), a Jacobean condemnation of ‘masculine’ women. Arguing that the drama of the early modern period was ‘full of set-piece denunciations of the “not-woman” in her many forms’, Jardine identifies Lady Macbeth as the archetype of Jacobean drama’s ‘not-woman’ (1983: 93, 97-8). Lady Macbeth and the witches Shakespeare sets up several parallels between Lady Macbeth and the witches: They mirror each other structurally in Act 1: 1.1, 1.3, 1.5 and 1.7 are private, female-dominated scenes, alternating with public, male-dominated ones. Both are figured as dangerous androgynes: the ‘unsexed’ Lady Macbeth and the ‘bearded’ witches; Both are associated with infanticide: Lady Macbeth imagines dashing out the brains of her child (1.7.54-9), while the witches’ potion includes a ‘Finger of birth-strangled babe’ (4.1.30). Against this, one might contrast the passive, motherly Lady Macduff (4.2). The witches: legitimation of patriarchy? Peter Stallybrass discusses the ‘social utility’ of witchcraft beliefs, arguing that beliefs in the ‘unnatural’ ‘imply and legitimate their opposite, the “natural”’ (2005: 190): ‘Witchcraft accusations are a way of reaffirming a particular order against outsiders, or of attacking an internal rival, or of attacking “deviance”. Witchcraft in Macbeth… is not simply a reflection of a pre-given order of things: rather, it is a particular working upon, and legitimation of, the hegemony of patriarchy.’ (2005: 190) King James and the North Berwick witchcraft trials, 1590 (and others) Daemonologie, 1597 The witches: heroines of the piece? ‘The witches are the heroines of the piece, however little the play itself recognises the fact, and however much the critics may have set out to defame them. It is they who, by releasing ambitious thoughts in Macbeth, expose a reverence for hierarchical social order for what it is, as the pious self-deception of a society based on routine oppression and incessant warfare. … The witches are exiles from that violent order, inhabiting their own sisterly community on its shadowy borderlands, refusing all truck with its tribal bickerings and military honours. … their words to Macbeth catalyse this region of otherness and desire within himself, so that by the end of the play it has flooded up within him to shatter and engulf his previously assured identity.’ (Eagleton 1986: 2) See the ending of Roman Polanski’s film version of Macbeth (1971)… Duncan in Holinshed In Shakespeare’s source, Holinshed’s Chronicles, Duncan and Macbeth are in fact not so very different from one another: ‘Makbeth, after the departure thus of Duncane’s sons, used great liberality towards the nobles of the realm, thereby to win their favour; and when he saw that no man went about to trouble him, he set his whole intention to maintain justice, and to punish all enormities and abuses which had chanced through the feeble and slothful administration of Duncane.’ Holinshed goes on to report that Macbeth ruled with justice for 10 years before becoming tyrannical. Duncan in Holinshed Holinshed: ‘The beginning of Duncane’s reign was very quiet and peaceable, without any notable trouble; but after it was perceived how negligent he was in punishing offenders, many misruled persons took occasion thereof to trouble the peace and quiet state of the common-wealth, by seditious commotions which had their beginnings in this wise.’ Modern productions which set Macbeth in the world of gang warfare tend to emphasise this aspect of the play. The Prologue to Penny Woolcock’s Macbeth on the Estate (1997) echoes Holinshed… References Chambers, E. K. (1923) The Elizabethan Stage, vol. 3, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Dickson, Andrew (2009) The Rough Guide to Shakespeare, London: Penguin. Eagleton, Terry (1986) William Shakespeare, Oxford: Blackwell. Jardine, Lisa (1983) Still Harping on Daughters, Women and Drama in the Age of Shakespeare, Brighton: Harvester Press. Ribner, Irving (1959) ‘Macbeth: The Pattern of Idea and Action’, Shakespeare Quarterly, 10:2, 147-59. Sinfield, Alan (1992) Faultlines: Cultural Materialism and the Politics of Dissident Reading, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Sofer, Andrew (2009) ‘How to Do Things with Demons: Conjuring Performatives in Doctor Faustus’, Theatre Journal 61: 1, 1-21. Stallybrass, Peter (2005) ‘Macbeth and witchcraft’ in John Russell Brown [ed.] Focus on Macbeth, London: Routledge, 189-209.