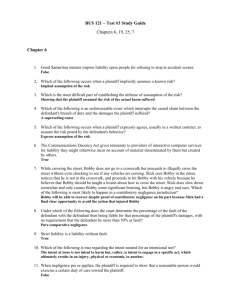

The but for test

advertisement

Anglo-American Contract and Torts Prof. Mark P. Gergen Class Six Res ipsa and factual cause Res ipsa loquitur Donoghue v. Stevenson (HL 1932)—decomposed snail in factorysealed opaque bottle of ginger beer. Decision is most known for holding manufacturer has a duty to whoever eventually consumed the beer no matter how many hands the bottle passes through. P cannot show how the snail came to be in the bottle. So how can she establish breach (negligence)? Negligence may be inferred if the manufacturer’s negligence is the probable (most likely) explanation of how the snail came to be in the bottle. Some say this result is similar to imposing strict liability for foreign substances in packaged food. Can you see why? Hammontree v. Jenner (Cal. App. 1971), p. 48 As a result of a sudden epileptic seizure, Jenner loses control of his car and crashes into the Hammontree’s shop, injuring Ms. Hammontree and causing significant property damage. The trial judge gave a res ipsa instruction along with a negligence instruction. See p. 49 bottom. This placed the burden on Jenner to persuade the jury of his story about the epileptic seizure. The traditional rule required that the instrumentality causing the harm be within D’s “exclusive control.” See pp. 57 & 59. As Colmanares explains at p. 60 this requirement is applied loosely to permit application of the doctrine if the plaintiff can sufficiently eliminate the possibility a third party caused the accident. The Restatement Third (2011) dispenses with the requirement of control. Third Restatement § 17 The factfinder may infer that the defendant had been negligent when the accident causing the plaintiff’s physical harm is a type of accident that ordinarily happens as a result of the negligence of a class of actors of which the defendant is the relevant member. I.e., does an accident of this type ordinarily occur because of negligence by someone in D’s position? This is a permissive inference in most jurisdictions. In the US, the party asking for a res ipsa instruction must present evidence based on which a reasonable person could find that the accident ordinarily occurs because of negligence by someone in D’s position. Colmenares Vivas v. Sun Alliance Ins. Co. (1st Cir. 1986)(Puerto Rico law). Escalator handrail in airport stops moving while steps continue to move. P falls injuring himself. This is a “direct action” against the Port Authority’s liability insurer. This is unusual. Usually the insurer is in the background. Sun brought a cross-claim against Westinghouse claiming accident was due to Westinghouse’s poor maintenance of escalator. One issue in the case is whether Colmenares may add Westinghouse as a defendant. Bottom p. 58 top p. 59 describes the evidence presented the short (2 day) trial. Oddly the plaintiff presented no expert testimony that this sort of thing usually does not happen if an escalator is properly maintained. Torruella argues at p. 63 that a directed verdict for D was proper because of the lack of such evidence. The majority focuses on a different problem. 1) Accept it is common knowledge that this sort of thing does not happen if the escalator is properly maintained. 2) But either Westinghouse or the Port Authority may have been at fault. There is no evidence to determine which of them was at fault. 3) So the plaintiff loses since he cannot establish which one of the two is at fault. The inability to establish who was at fault would not matter if Westinghouse’s fault could be imputed to the Port Authority. Recall the snail in the bottle . . . someone in the factory probably messed up, but we don’t know who. This is no problem for the negligence of an employee is imputed to the employer. But Westinghouse is an independent contractor. Someone who employs a independent contractor usually is not responsible for their torts. The court invokes an exception to this rule for “nondelegable duties.” See pp. 61-62. So the dispute as to who among them is responsible is between Westinghouse and the Port Authority. P hasn’t won yet. The case is remanded so the jury can decide whether it is likely the accident was due to the negligent maintenance of the escalator. The but for test To determine whether negligent act x caused injury y you ask whether y (probably) would not have occurred but for x (i.e., without the occurrence of x). A useful heuristic . . . Imagine the accident is filmed. Run the film back from the present, correct the wrong (and only the wrong), then run the film forward to see how things would have turned out had the wrong not occurred. In the US, the issue of cause in fact goes to the jury if reasonable people could disagree whether it is more likely than not that y would not have occurred had x not occurred. D drives 45 km per hour in 40 km per hour zone, as is customary. He runs into P a small child who darts into D’s path from between parked cars. D is negligent only with respect to speeding. He could not have seen the child approaching the street because of the parked cars. The evidence shows D was 1 meter or less from the child when she emerged from between the cars. Is D’s speeding but for cause of hitting P? What if the evidence shows D was around 10 meters from the child when she emerged from between the cars? Sometimes courts do not apply the but-for test. •“Liberal rule of causation” in some cases of irreducible causal uncertainty (we won’t look at materials on this). •Loss of chance •Over-determined consequences Loss of chance Herskovits and Hotson, p. 69 (bottom) D negligently fails to diagnose P’s cancer. This deprives P of what would have been a 14% chance of living? Is the negligence a “but for” cause of P’s death? Did the negligence harm P? Herskovits allows recovery of damages for the loss chance, i.e., 14% of wrongful death damages. Hotson rejects the theory. Multiple tortfeasors and multiple causes In most cases with multiple wrongs the wrongs will each be a necessary cause of the loss. A car and a bus collide in an intersection as the result of the negligence of both drivers. P, a passenger in the bus, is injured. Each drivers’ negligence is a but for cause of P’s injury. Multiple wrongdoers each of whose wrong is a necessary cause of an indivisible harm: •Each wrongdoer is jointly and severally liable for the harm. •Plaintiff may choose to sue one or more (joinder of all is not mandatory). Wrongdoers may try to bring each other into the litigation through cross claims. •If a wrongdoer pays more than its share of the liability, then it may seek contribution from the other(s). •If a wrongdoer cannot be made to pay its share, then the other wrongdoers bear the loss and not the plaintiff. If a harm is divisible, then a wrongdoer is liable only for its part. Multiple sufficient causes Concurrent wrongs each sufficient to cause the harm C and D each concurrently and negligently dump 50 lbs of toxins into P’s lake, killing the fish. 40 lbs of toxins suffices to kill the fish. Is either C or D causally responsible under the but-for test? Nevertheless both C and D are held responsible. Does this seem right to you? Why? A competing cause is not a wrong against P E negligently starts a fire, which joins with a naturally started fire. The combined fire spreads to destroy P’s property. E is liable even if it is more likely than not that the naturally started fire would have destroyed P’s property in any event. I.e., the concurrent cause need not be a wrong. Two rationales Deterrence—why should E diminish liability as a result of luck (the other fire)? Uncertainty—we cannot be certain that natural fire would have destroyed P’s property; resolve doubts against E, who is a wrong-doer. Special theories of aggregate responsibility Concerted action (as background) Alternative liability (Summers v. Tice) Market share liability (Sindell --DES cases) Concerted action “an understanding, express or tacit, to participate in ‘a common plan or design to commit a tortious act.’” A and B race each other on a public highway. A collides with P. B may be held liable either on a theory that his racing was cause in fact of P’s injury or on a theory of concerted action. Alternative liability (Summers v. Tice) E and F simultaneously, and negligently, shoot shotguns in P’s direction. P is hit by a single pellet in the face. P must join both E and F in the suit. The burden is cast on E and F to prove the pellet that hit P did not come from their gun. If they can’t do so, then they are joint and severally liable. Alternative Liability E and F simultaneously, and negligently, shoot shotguns in P’s direction. P is hit by a single pellet in the face. Multiple Sufficient Cause C and D each concurrently and negligently dump 50 lbs of toxins into P’s lake, killing the fish. 40 lbs of toxins suffices to kill the fish. In the case of the two shooters we know only one of them shot P. In the case of the two polluters both dumped sufficient pollution to kill the fish. Market Share Liability M1, M2, M3 . . . .Mn each and all manufacture the same fungible defective product. P is injured using the product as a result of the defect. P cannot show who manufactured the product he used. This is similar to alternative liability. Every manufacturer acted negligently. But we don’t know who manufactured the product injuring P. Sindell v. Abbott Labs (Cal 1980). P is not required to join all the manufacturers (which is required for alternative liability), but each is liable only for a share of the loss based upon its market share. The DES cases—what prompted market share liability Child-bearing women were prescribed DES to prevent. miscarriage. It was learned much late that DES leads to a heretofore unusual form of cervical cancer in daughters. •Signature disease •Long latency •Chemical compound was the same for all producers •Large number of manufacturers •Often it was impossible to determine which firm produced DES ingested by a claimant Courts have not applied the doctrine to hold manufacturers of nonfungible dangerous products liable based on their market share (e.g., lead paint). “The Yellow Cab problem.” P is struck by a negligently driven Yellow Cab. There are two Yellow Cab companies in town that had cabs operating in the area of the accident at the time of the accident. One had five cabs in the area, the other two. This is only evidence bearing on the ownership of the cab that struck P. Is this evidence sufficient to hold either or both companies liable? If not, then can you distinguish Summers v. Tice and the DES cases.