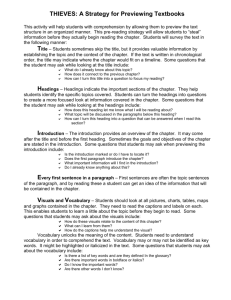

Determining Purpose Strategy: THIEVES

advertisement

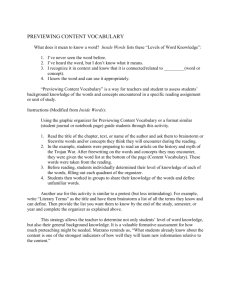

Literacy Tips and Tricks Practical Strategies for Fostering Literacy Across the Content Areas In search of a purpose Why do our students read? Outside of school, reading takes on many different purposes for them—to connect with friends, to learn about things of interest, or to just have fun. But what about reading done specifically for school? Do students have purposes for the reading that we as teachers assign? According to Cris Tovani, author of I Read It, But I Don’t Get It, students rarely get the chance to set their own purpose for their academic reading. But more than that, the purposes that students are provided with by their teachers can be just as limited. Teacher purposes might simply be to “read chapter 10 as there will be a quiz over it on Monday” or “finish Acts 2-3 so that you can write a character analysis.” Unfortunately, such vague purposes as the ones above don’t give students enough information to separate out what is important from what is not. As I was preparing a model lesson for a class last week, I was looking at the current physical science textbook at the high school. I knew that most of the classes would soon be starting on chapter 12, so I decided that I would design my lesson on that particular chapter. As I dug into the text, everything seemed so dense, so full of information that everything—and I mean everything—seemed important. And I began to wonder if, like me, the students who would eventually read this book would struggle in determining what vocabulary terms, processes, and facts were most important. So, how to we tackle this issue? The most obvious way is, as teachers, to provide students with a specific purpose before they read. For example, a science teacher assigning reading from chapter 12 might simply tell students that they need to be able to describe the properties of electromagnetic waves and why those waves are important to us in today’s society. However, as the Chinese proverb says, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” What is most essential, then, is to instead teach students why it is important to have a purpose when they read and how they can establish one. According to Cris Tovani, students who read difficult text without a purpose often express the following complaints: I don’t care about the topic. I can’t relate to the topic. I daydream and my mind wanders. I can’t stay focused. I just say the words so I can be done. So how can teachers help students set a purpose when reading tough texts? Figure previewing is a great way to help students build background knowledge prior to reading and help them create questions they hope to find the answers to when reading. In addition, using the THIEVES strategy has students use various text features to identify what they already know about the subject and what information the text might provide. Both of these strategies have students using defined graphic organizers in the beginning, but as students become proficient at the strategies, they can do these previews and set their own purposes entirely in their heads. Determining Purpose Strategy: Figure Previewing This strategy is extremely valuable in texts that use diagrams, process illustrations, or charts and graphs. Science textbooks are a natural fit as pictures explain cycles and processes better than written text alone. Not only do students record their observations about what they see in the figures, they also write questions about their own wonderings about the topic or the text. These questions give students a purpose to read on as most of us don’t like unanswered questions. And, even if students think they already know the answer, they like to prove themselves right. What Is It? Figure previewing has students examine the figures, pictures, and illustrations with the captions to help them develop a basic understanding of the material they are going to read, activate their prior knowledge, and create questions they hope to find answers to in the text. What Does It Do? In text-based previewing, students use figures, tables, and graphics to recall what they observe and what these visual elements made them wonder about. How Do I Use It? Step 1: Model the Process. o Talk through a figure preview with the students, having them turn pages as you do. Record information on an overhead copy of the figure previewing worksheet. Step 2: Students Complete Visual Previewing o Give students a chart to record observations on. o Have students record not only what they see in each picture, but what questions it brings to mind. Step 3: Have Students Share Questions and Predictions See the following pages for an example of a completed figure previewing chart. A blank copy of the chart is also available at the SHSD Literacy website using the address below. Simply look under the Chapter Previewing section: http://www.sthelens.k12.or.us/17412082521156117/blank/browse.asp?a=383&BMDRN=2000&BCOB=0&c=5 7073&17412082521156117Nav=|&NodeID=190#Chapter. Simply look under “Chapter Previewing.” Figure Previewing: Fossilization Directions: To gain some background knowledge for this reading selection, look at each figure/picture/ chart listed below. In the space provided, describe what you see in each of the elements and write at least one “I Wonder” question about each figure. Figure What I Observed What I Wondered Fig 1-1 The paleontologist is chipping away at the side of a stone hill looking for fossils in the rock. Where does the term paleontologist come from? There is a series of pictures: Fig 1-2 o o o a dead fish in shallow water sediment covering the fish the sediment becoming rock; part of the fish is preserved Is the presence of shallow water necessary in forming fossils? Fig 1-3 A mountain with petrified tree stumps at the base. The tree stumps have been turned to stone. I wonder how the tree stumps became petrified…and where you could find them. Fig 1-4 Pictures of fossils showing an ancient animal. I noticed that the fossil mold is raised and the fossil cast is indented. I don’t understand the use of the terms mold and cast. Fig 1-5 A very old bug fossil is shown. I don’t understand the term carbon film. Fig 1-6 Footprints of a dinosaur in desert stone. The dinosaur appears to have had three toes. I wonder what the name of the dinosaur is. Fig 1-7 Ancient bugs preserved in amber. What’s amber? Determining Purpose Strategy: THIEVES The term THIEVES is a mnemonic that students can use to help them preview nonfiction text, especially textbooks. As part of the strategy, students look at the Title, Headings, Introduction, Every first sentence, Visuals and Vocab, End-of-chapter questions, and chapter Summary. What Is It? THIEVES has students examine some of the common structures of informational text to discover what the reading might be about. Students can use titles, summaries, headings, and subheadings as part of the preview, but they can also use vocabulary terms, figures, pictures, and illustrations with the captions to preview as well. What Does It Do? THIEVES helps students pinpoint information they gain from main areas of the text, connect that knowledge to their prior knowledge, and create questions they hope to answer to determine purpose. How Do I Use It? Step 1: Model the Process. o Talk through a THIEVES preview with the students, having them turn pages as you do. Be sure to model aloud your thinking about the different text elements. o Once you have completed the think aloud, show students how that information can be recorded on the THIEVES graphic organizer. Record information on an overhead version of the organizer. Remind students that when they become more comfortable with the process, THIEVES can be done entirely in their heads. Step 2: Students Complete a THIEVES graphic organizer with a short text. o Give students a chart to fill out with a small group. Give each group member copies of a short, high-interest text that they can conduct a THIEVES analysis on. o Once students have finished THIEVES with the group, share our responses and record on a class copy on the overhead. Step 3: Students Engage in Partner and Individual Written THIEVES Step 4: Students use THIEVES independently (whether mentally or using the graphic organizer) to create questions and purpose. See the following page for an example of a THIEVES graphic organizer that could work in any class. In addition, the following website has additional lessons and resources for lesson planning. http://www.readwritethink.org/lessons/lesson_view.asp?id=112 THIEVES Stealing Valuable Information Before Textbooks Know What Hit Them What am I stealing? Title What is the title? Headings What headings are in the chapter? Introduction What important info can I find in the introduction or beginning text features? Every First Sentence Summarize the information you receive in the first sentence of each paragraph. Visuals/Vocab What information can be found in charts/graphs/pictures/ captions? What key words are listed in the chapter? End-of-Chapter ?s What information do I need to know from the chapter based on the questions I need to answer? Summary What are the main ideas that the summary addresses? What do I already know about what I am stealing? What questions might I find answers to as I read?