File

advertisement

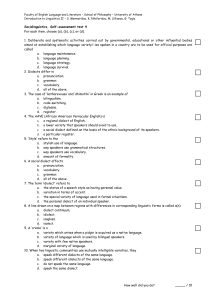

Languages, Dialects, and Varieties Wardhaugh Chapter 2 Sociolinguistics “to study the relationship between language and society” (Ferguson 1966) • possible interactions between language and society – social structure influence – language influence society – mutual influence – no influence Small group discussion: Try to characterize your own speech – how is it similar and how is it different than others around you? What is the difference between language and dialect? Variety is a term used for to replace both terms - Hudson says “a set of linguistic items with similar distribution” Variety is some linguistic shared items which can uniquely be associated with some social items a definition that allows us to say that all of the following are varieties: Canadian English, London English, the English of football commentaries, and so on. According to Hudson, this definition also allows us ‘to treat all the languages of some multilingual speaker, or community, as a single variety, since all the linguistic items concerned have a similar social distribution.’ less even than something traditionally referred to as a dialect. A variety can therefore be something greater than a single language as well as something less, Hudson and Ferguson agree in defining variety in terms of a specific set of ‘linguistic items’ or ‘human speech patterns’ (presumably, sounds, words, grammatical features, etc.) which we can uniquely associate with some external factor (presumably, a geographical area or a social group). Standard English, Cockney, lower-class New York City speech, Oxford English, legalese, cocktail party talk, and so on. For many people there can be no confusion at all about what language they speak. For example, they are Chinese, Japanese, or Korean and they speak Chinese, Japanese, and Korean respectively. It is as simple as that; language and ethnicity are virtually synonymous A Chinese may be surprised to find that another person who appears to be Chinese does not speak Chinese, and some Japanese have gone so far as to claim not to be able to understand Caucasians who speak fluent Japanese. Just as such a strong connection between language and ethnicity may prove to be invaluable in nation-building, it can also be fraught with problems when individuals and groups seek to realize some other identity Most speakers can give a name to whatever it is they speak. On occasion, some of these names may appear to be strange to those who take a scientific interest in languages, but we should remember that human naming practices often have a large ‘unscientific’ component to them. Census-takers in India find themselves confronted with a wide array of language names when they ask people what language or languages they speak. Names are not only ascribed by region, which is what we might expect, but sometimes also by caste, religion, village, and so on. Moreover, they can change from census to census as the political and social climate of the country changes. While people do usually know what language they speak, they may not always lay claim to be fully qualified speakers of that language. They may experience difficulty in deciding whether what they speak should be called a language proper or merely a dialect of some language. Such indecision is not surprising: exactly how do you decide what is a language and what is a dialect of a language? What are the essential differences between a language and a dialect? Haugen (1966a) has pointed out that language and dialect are ambiguous terms. Ordinary people use these terms quite freely in speech; for them a dialect is almost certainly no more than a local non-prestigious (therefore powerless) variety of a real language. In contrast, scholars often experience considerable difficulty in deciding whether one term should be used rather than the other in certain situations. the confusion goes back to the Ancient Greeks. distinct local varieties each variety having its own literary traditions and uses, e.g., Ionic for history, Doric for choral and lyric works, and Attic for tragedy. Later, Athenian Greek, the koiné – or ‘common’ language – became the norm for the spoken language The situation is further confused by the distinction the French make between un dialecte and un patois. The former is a regional variety of a language that has an associated literary tradition, whereas the latter is a regional variety that lacks such a literary tradition. used pejoratively; it is regarded as something less than a dialect because of its lack of an associated literature. Dialect is used both for local varieties of English, e.g., Yorkshire dialect, and for various types of informal, lower-class, or rural speech. ‘In general usage it therefore remains quite undefined whether such dialects are part of the “language” or not. In fact, the dialect is often thought of as standing outside the language. . . . As a social norm, then, a dialect is a language that is excluded from polite society’ It is often equivalent to nonstandard or even substandard, when such terms are applied to language, and can connote various degrees of inferiority, with that connotation of inferiority carried over to those who speak a dialect. What is the difference between language and dialect? There are a lot of situations that show language versus dialect isn’t clear Chinese Norwegian/Swedish Croatian and Serbian Hebrew Arabic Spanish? What is the difference between language and dialect? Need to discuss issues of solidarity and power - How do these play into the definitions of a variety as a dialect or language? “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy” Power requires some kind of asymmetrical relationship between entities: one has more of something that is important, e.g. status, money, influence, etc., than the other or others. A language has more power than any of its dialects. It is the powerful dialect but it has become so because of non-linguistic factors. Standard English and Parisian French are good examples. Solidarity, on the other hand, is a feeling of equality that people have with one another. They have a common interest around which they will bond. A feeling of solidarity can lead people to preserve a local dialect or an endangered language to resist power, or to insist on independence. It accounts for the persistence of local dialects, the modernization of Hebrew, and the separation of Serbo-Croatian into Serbian and Croatian. Dialect continuum - one definition of dialect is a mutually intelligible variety of a language. A continuum exists in geography if you travel from NW France to SE Italy or SW Spain - all related languages. Each adjacent village can understand each other regardless of where the political borders are. BUT Paris, Madrid and Rome speak varieties that are not mutually intelligible, therefore separate languages Dialect at one time indicated a geographical as well as linguistic distinction standardization Codification of language: grammars, spelling books, dictionaries, literature. We can often associate specific items or events with standardization, e.g., Wycliffe’s and Luther’s translations of the Bible into English and German, respectively, Caxton’s establishment of printing in England, and Dr Johnson’s dictionary of English published in 1755. Standardization also requires that a measure of agreement be achieved about what is in the language and what is not. Once a language is standardized it becomes possible to teach it in a deliberate manner. It takes on ideological dimensions – social, cultural, and sometimes political – beyond the purely linguistic ones. Standard English is that variety of English which is usually used in print, and which is normally taught in schools and to non-native speakers learning the language. It is also the variety which is normally spoken by educated people and used in news broadcasts and other similar situations. The difference between standard and nonstandard, it should be noted, has nothing in principle to do with differences between formal and colloquial language, or with concepts such as ‘bad language.’ Standard English has colloquial as well as formal variants, and Standard English speakers swear as much as others. What is “Standard English” • Variety which is: – In most print sources? – Taught in schools? – The version ESL students study? Madonna vs. Guy Richie • Sometimes standard or RP accent is valued • Sometimes dialect is valued • Elitist impulse vs socialist impulse in dialectic Bell’s criteria for the difference between language and dialect? Vitality • • • • Manx and Cornish dead Latin too is dead Dialects also die But other dialects (and languages) are born and the classical languages are still vital parts of Western culture. Hebrew/Irish Historocity • Groups link sense of identity with language. Unifying force? Divisive as well? • a language of identity - belongs to its speakers - Germany and German language Chinese Autonomy • Speakers of a language of dialect may feel different and special. - a language is felt to be different by its speakers - Catalan? problems with pidgin and creole langs - Chinese again Reduction • Other linguistic groups recognize their dialect as being substandard, though they may love it nevertheless. In fact, the fact that it is substandard can be thought of as a badge of honor. Cockney is a good example as is Glaswegian, Mancunian. Surfer dialect too. What others? functionally limited, particularly to less prestigious domains - linguistic insecurity - pidgins Mixture Feelings about the purity or lack of purity of a dialect. People feel that their “mixed” speech is debased, deficient, degnerate, Good speakers Bad speakers Most groups recognize better and worse dialects and pronunciations, though the heirarchy here is relative and shifting. Parisien French, Oxford EnglishDE FACTO NORMS With these criteria, different varieties meet them differently Language vs Dialect • Whatever else it may or may not be, a dialect is a subset of a language? Vernacular and Koine • Vernacular: the speech passed down from parent to child as primary mode of communication (Do parents pass down language?) • Koine: speech shared by people of different vernaculars Yikes! • Look at all the discussion questions on pp. 40-43. I think 1, 11, and 17 are worth talking about. Any others we might discuss? Dialect vs patois • Dialect: has a literature • Patois: purely oral, rural, lower class Dialect vs Accent • Dialect: vocabulary, syntax, pronunciation, etc.. • Accent: pronunciation • Everybody speaks English with some kind of accent. Thirdy, La’in, dune, dude? Discussion questions • Let’s look at 1-6 on page 46-7, in groups for 15 minutes then general discussion. Social dialects • Dialect associate with group identity apart from geographical identity. Black English, Jewish English, Surfer Dudian, Academic English? Styles, Registers, Beliefs • Formal vs informal • Occupation lingo • Dialect, style, register are largely independent High/low vs better/worse • We often don’t like speakers who speak with a posh accent, even though/because we recognize the social superiority or “correctness” of the speech. In fact, rural dialects though recognized as “incorrect’ tend to be preferred over city dialects. We tend to like older, more familiar ways of speech. Simple over complex. Bush beats Kerry? As Wardhaugh points out, despite what we “know” people tend to believe and to teach value judgments about lanaguage and dialect. People without university educations tend to think of their speech and grammar as inferior. They believe pundits who tell them about “proper” grammar and speech. Regional Dialects Regional variation in the way a language is spoken is likely to provide one of the easiest ways of observing variety in language. As you travel throughout a wide geographical area in which a language is spoken, and particularly if that language has been spoken in that area for many hundreds of years, you are almost certain to notice differences in pronunciation, in the choices and forms of words, and in syntax. There may even be very distinctive local colorings in the language which you notice as you move from one location to another. Such distinctive varieties are usually called regional dialects of the language. As we saw earlier (p. 28), the term dialect is sometimes used only if there is a strong tradition of writing in the local variety. When a language is recognized as being spoken in different varieties, the issue becomes one of deciding how many varieties and how to classify each variety. Dialect geography is the term used to describe attempts made to map the distributions of various linguistic features so as to show their geographical provenance. For example, in seeking to determine features of the dialects of English and to show their distributions, dialect geographers try to find answers to questions such as the following. Is this an rpronouncing area of English, as in words like car and cart, or is it not? What past tense form of drink do speakers prefer? What names do people give to particular objects in the environment, e.g., elevator or lift, petrol or gas, carousel or roundabout? Sometimes maps are drawn to show actual boundaries around such features, boundaries called isoglosses, so as to distinguish an area in which a certain feature is found from areas in which it is absent. When several such isoglosses coincide, the result is sometimes called a dialect boundary. Then we may be tempted to say that speakers on one side of that boundary speak one dialect and speakers on the other side speak a different dialect. On the other hand, humans are naturally very smart about language. We deduce and intuit a great deal about speakers. How can do we make these judgments? How can we know when we are right and wrong? Would we be able to spot a Martian trying to pass himself off as a native English speaker? As I indicated in chapter 2, it is possible to refer to a language or a variety of a language as a code. The term is useful because it is neutral. Terms like dialect, language, style, standard language, pidgin, and creole are inclined to arouse emotions. In contrast, the ‘neutral’ term code, taken from information theory, can be used to refer to any kind of system that two or more people employ for communication. (It can actually be used for a system used by a single person, as when someone devises a private code to protect certain secrets.) Why do people choose to use one code rather than another? what brings about shifts from one code to another ? and why do they occasionally prefer to use a code formed from two other codes by switching back and forth between the two or even mixing them? people are nearly always faced with choosing an appropriate code when they speak. Very young children may be exceptions, as may learners of a new language (for a while at least) and the victims of certain pathological conditions. In general, however, when you open your mouth, you must choose a particular language, dialect, style, register, or variety – that is, a particular code. You cannot avoid doing so. Moreover, you can and will shift, as the need arises, from one code to another. What are some of the factors that influence the choices you make? Language choice • code switching – changing from one language to an other • situational switching • metaphorical switching • code-mixing – speaking in one language but using pieces from another • style shifting – standard English vs. afro-american vernacular • language borrowing Diglossia • Ferguson’s definition (1959): the side-by-side existence of historically & structurally related language varieties – the Low variety takes over the outdated High variety • Fishman’s reformulation (1967): a diglossic situation can occur anywhere where two language varieties (even unrelated ones) are used in functionally distinct ways – the Low variety loses ground to the superposed High variety – problematic as it creates an opposite situation to widespread bilingualism Fishman’s reformulation + diglossia - diglossia + bilingualism Everyone in a community knows both H and L, which are functionally differentiated An unstable, transitional situation in which everyone in a community knows both H and L, but are shifting to H - bilingualism A completely egalitarian speech community , where there is no language variation Speakers of H rule over speakers of L Diglossic situation • Four examples: Situation Arabic Swiss German Haitian Greek 'high' variety Classic Arabic 'low' variety Various regional colloquial varieties Standard German Swiss German Standard French Haiti Creole Katharévousa Dhimotiki Diglossic situation: functions of H vs. L Situation Sermon in church or mosque Instructions to servants, waiters, worksmen, clerks Personal letter Speeches in parliament, political speeches University lecture Conversations with family, friends, colleagues News broadcasts Radio 'soap opera' Newspaper editorial, new story, caption on picture Caption on political cartoon Poetry Folk literature H L x x x x x x x x x x x x Ferguson, Charles. 1972. Diglossia. In: Pier Paolo Giglioli (ed.). Language and Social Context. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 232-251. In: Ralph Fasold. 1985. The Sociolinguistics of Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 35. • You do not use an H variety in circumstances calling for an L variety, e.g., for addressing a servant; nor do you usually use an L variety when an H is called for, e.g., for writing a ‘serious’ work of literature. a risky endeavor • Norman Conquest of 1066, English and Norman French coexisted in England in a diglossic situation with Norman French the H variety and English the L. However, gradually the L variety assumed more and more functions associated with the H so that by Chaucer’s time it had become possible • to use the L variety for a major literary work. • • • • • • • • • • The H variety is the prestigious, powerful variety; H variety is more beautiful, logical, and expressive than the L variety. it is deemed appropriate for literary use, for religious purposes, and so on. There may also be considerable and widespread resistance to translating certain books into the L variety, e.g., the Qur’an into one or other colloquial varieties of Arabic or the Bible into Haitian Creole or Demotic Greek. (We should note that even today many speakers of English resist the Bible in any form other than the King James version.) feeling concerning the natural superiority of the H variety is likely to be reinforced by the fact that a considerable body of literature will be found to exist in that variety and almost none in the other. • • • • • • • the L variety lacks prestige and power. The folk literature associated with the L variety will have none of the same prestige; it may interest folklorists and it may be transmuted into an H variety by writers skilled in H, but it is unlikely to be the stuff of which literary histories and traditions are made in its ‘raw’ form. Another important difference between the H and L varieties is that all children learn the L variety. Some may concurrently learn the H variety, but many do not learn it at all • • The H variety is also likely to be learned in some kind of formal setting, e.g., in classrooms or as part of a religious or cultural Indoctrination. H variety is ‘taught,’ Teaching requires the availability of grammars, dictionaries, standardized texts, and some widely accepted view about the nature of what is being taught and how it is most effectively to be taught. • • • • whereas the L variety is ‘learned.’ There are usually no comparable grammars, dictionaries, and standardized texts for the L variety, and any view of that variety is likely to be highly pejorative in nature. The L variety often shows a tendency to borrow learned words from the H variety, particularly when speakers try to use the L variety in more formal ways.The result is a certain admixture of H vocabulary into the L. Bilingualism • Individual bilingualism – two native languages in the mind – Fishman: “ a psycholinguistic phenomenon” • Societal bilingualism – A society in which two languages are used but where relatively few individuals are bilingual – Fishman: “a sociolinguistic phenomenon” • Stable bilingualism – persistent bilingualism in a society over several generations • Language evolution: – Language shift – Diglossia BENEFITS OF BILINGUALISM (California Department of Education, Language Policy and Leadership Office) •Enhanced academic and linguistic competence in two languages •Development of skills in collaboration & cooperation •Appreciation of other cultures and languages •Cognitive advantages •Increased job opportunities •Expanded travel experiences •Lower high school drop out rates •Higher interest in attending colleges and universities BILINGUALISM AND MOTIVATIONAL FACTORS ”The more motivated you are the quicker you learn an additional language” (evidence from a number of studies) Gardner & Lamberts (1972): •Integrative motivation = social motivation (to integrate in a specific culture to fit in to a social group.) •Instrumental motivation = motivation for practical reasons (to do well at school get to university) Conflicting evidence in later research with regard to the importance and distinctiveness of the two motivational factors Relationships between knowing one’s ancestral language and affective factors (an U.S. study by Wharry, 1993) Subjects: Native American, Vietnamese American, Hispanic American college students Those who were bilingual tended to: -believe that learning their ancestral language was important -had integrative reasons for that (e.g., heritage, family relations) -believe that their parents wanted them to learn the ancestral language -had clearcut ethnic identity Pidgin and Creole • Ferguson (1966) distinguished between five language types based on prestige (p) and vitality (v): – Vernacular • unstandardized native language of speech community (-p, +v) – Standard • native language of a speech community codified in dictionaries and grammars (+p, +v) – Classical • language codified in dictionaries and grammars which is no longer spoken (+p, -v) – Pidgin • hybrid language with lexicon from one language and grammar from another language (-p, -v) – Creole • language acquired by children of speakers of pidgin, or subsequently by speaker or Creole (-p, ±v) Pidgin and Creole 1.Pidgin language is nobody's native language; may arise when two speakers of different languages with no common language try to have a makeshift conversation. Lexicon usually comes from one language, structure often from the other. Because of colonialism, slavery etc. the prestige of Pidgin languages is very low. 2. Creole is a language that was originally a pidgin but has become nativized, i.e. a community of speakers claims it as their first language. Next used to designate the language(s) of people of Caribbean and African descent in colonial and excolonial countries (Jamaica, Haiti, Mauritius, Réunion, Hawaii, Pitcairn, etc.) Language shift in different communities Migrant minorities • Typically, migrants are virtually monolingual in their mother tongue, their children become bilingual, but the grandchildren turn monolingual in the language of the host country. • At first, migrants use the host’s language in limited domains and reserve the home domain for their mother tongue, but soon the host language gradually infiltrates their homes through their children. • Children encounter the host languages first on TV but are compelled to using it for survival at school. Then this language turns to be the code for communicating with their siblings and friends. Most families eventually shift from using their mother tongue at home to using the host country’s language. • There is also pressure from the hosts on migrants to conform, which results in language shift from their mother tongue to the host language. • Language shift may take three to four generations to occur. Language shift in different communities Non-migrant communities • Language shift does not always result from migration; it may result from political, economic, or social changes within the community of speakers. Burgenland: A bilingual community for 400 years. Hungarian was originally associated with farming and peasants and German with industry. Then a diglossic situation resulted in Hungarian as the L-variety and German as the Hvariety. Eventually, German became the language for social and economic progress and the domains for Hungarian retracted; German is now spoken even at home. Language shift in different communities Non-migrant communities • It is almost a rule that the more domains in which a minority language is used, the more likely it will be maintained. • Where minority languages have resisted language shift the longest, there has been at least one exclusive domain for the minority language. • Generally, the religious domain is the most resistant to language shift. Until now, for example, Latin, Hungarian, and Arabic are used in Latin Roman Church, Oberwart prayers, and Islamic rites. Language Death & Shift • When all the people who speak a language die, the language dies with them. • Immigrants shift to the language of the majority in two to three generations, but that does not constitute the death of their ethnic language because it continues to be spoken by the majority in their old country of origin. • Language death is similar to language shift in being a gradual process, in which the functions of one language are taken over in one domain after another by another language. • Language death is manifested in a gradual loss of fluency and competence by its speakers; competence gradually erodes over time. UNESCO RED BOOK ON ENDANGERED LANGUAGES: EUROPE (i) extinct languages other than ancient ones (e.g. Kemi Sámi, Dalmatian) (ii) nearly extinct languages with maximally tens of speakers, all elderly (e.g., Ume Sámi, Livonian) (iii) seriously endangered languages with a more substantial number of speakers but practically without children among them (e.g., Ingrian, Breton) (iv) endangered languages with some children speakers at least in part of their range but decreasingly so (e.g., Irish Gaelic, Friulian) (v) potentially endangered languages with a large number of children speakers but without an official or prestigious status (low Saxon, Corsican) http://www.helsinki.fi/~tasalmin/europe_index.html#extinct Language Death & Shift Differences between language shift and language death: • Language Shift: This is a process in which one language displaces another in the linguistic repertoire of a community. • Language Death: This is a process that occurs when a language is no longer spoken naturally anywhere in the world. Factors affecting language shift 1. Patterns of language use: Socio-economic factors - determine in which domains the minority language may be used the more domains a minority language is used in, the more chances there is to maintain it 2. Demographic factors: (a) large enough community of speakers (b) the community is able to isolate itself from the influences of the majority (c) there is a high frequency of contact with the homeland 3. Attitudes to the minority language: (a) pride and respect of the language (b) symbol of the ethnic identity (c) the language has international status Factors affecting language shift Economic, Social, and Political Factors • A community sees an important reason for learning the second language: 1. Economic: Obtaining well-paying jobs 2. Political: Allegiance to the government 3. Social: Fitting in • Bilingualism is usually an indicator, a forerunner, of language shift; although stable diglossic communities demonstrate that bilingualism does not always result in language shift. • Language shift is inevitable without active language maintenance. Thinking that a language is no longer needed or that it is in any danger of disappearing may result in language loss. • Rapid shift occurs when speakers are eager to ‘fit in’ or ‘get on’ in society; young people and job seekers are the fastest to shift languages. Factors affecting language shift Demographic Factors 1. Social integration leads to language shift; social isolation, on the other hand, may result in resistance to language shift. – Isolated rural communities of minorities tend to resist language shift. E.g., Ukrainians in the Canadian farmlands. – Improved roads, buses, TV, telephone, internet are agents of language shift. 2. Size of community of speakers tends to influence language shift. Where there is a large number of speakers of the minority language, language shift is slowest. – To maintain a language, there must be people who can use it with one another; the larger the group, the more social pressure to speak the ethnic language. – Shift tends to occur faster in some groups than in others. Factors affecting language shift Demographic Factors 3. Intermarriage can accelerate language shift towards the language of the partner who speaks the language of the majority, unless multilingualism is the norm in society. – Mothers tend to influence language change either by accelerating it towards the language of the majority or by slowing it down if her native language is that of the minority. Factors affecting language shift Attitudes and Values 1. Language shift tends to be faster among communities where the ethnic language is not highly valued. 2. It also occurs where the ethnic language is not seen as a symbol of identity. – Language is an important component of identity and culture; maintaining a group’s identity and culture is usually important to it, so they maintain their ethnic language to maintain their identity. – Positive attitudes of speakers support efforts to use the ethnic language in a variety of domains, these attitudes help people resist the pressure from the majority group to shift to their language. 3. The international status of the ethnic language either accelerates or slows down language shift e.g. French in Maine (U.S.A.) and Quebec (Canada). How Can a Minority Language be Maintained? There are certain social factors which help resist wholesale language shift: 1. The language is a symbol of identity; e.g., the languages of the Polish and Greeks in Anglo-Saxon countries. 2. Speakers live near each other and socialize and worship with each other frequently; e.g., Indians & Pakistanis in Birmingham and the Chinese in Chinatowns. 3. There is frequent contact with the homeland through regular visits and frequent new immigrants. 4. Discouraging inter-marriages helps maintain the language of the minority. 5. Using the minority language in the extended family helps maintain this ethnic language. 6. Institutional support through education, law and administration, religion, and the media is crucial to language maintenance. Language Revival • When some communities realize that their ethnic language is in danger of disappearing, they consciously work to revitalize or bring to life the language; Irish, Welsh, Scottish, and Maori are cases in point. • The success of language revival efforts depends on (a) how far the language loss has occurred, (b) how determined its speakers are in reviving it, and (c) whether the economic factor is conducive or not (encouraging or discouraging). • Hebrew was effectively dead for 1700 years but got revived and is now spoken as an everyday native language of communication. • There is no magic formula for guaranteeing language maintenance; similar factors apparently result in a stable bilingual situation in some communities but language shift in others. • Pressures towards language shift occur more in monolingual communities than multilingual communities that consider the existence of more than one language as normal.