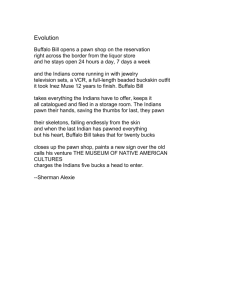

How the West was Spun - Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild

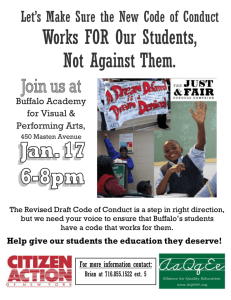

advertisement