individual-confession-and-forgiveness

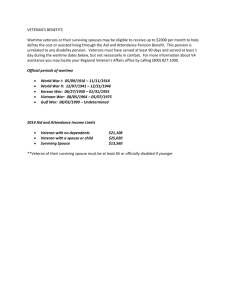

advertisement

Individual Confession and Forgiveness copyright@John Sippola (2013) Then David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the Lord.” Nathan replied, “The Lord has taken away your sin. You are not going to die.” 2 Samuel 12:13 There is no power more unalterable than the power of forgiveness. Guy Sajer (German WWII Veteran) The Forgotten Soldier In this workbook the word confidant is used as a general, technical term. A confidant can be anyone who inspires confidence in the veteran: a clergy, parish nurse, caregiver, family member or friend. The primary goal of this section is to inspire confidants in the practice of forgiveness in their work with veterans. Veterans often seek help first from a clergy – more, in fact, that all other therapists and specialists combined. The primary reasons for this are: confidentiality, protection of career (clergy are off-record), and, most importantly, the spiritual nature of their concerns. At the center of their many spiritual concerns is the need for forgiveness. Forgiveness is the centerpiece of the gospel. It is at the heart of what Christ and His church have to offer. And, forgiveness is precisely what many veterans need and want when they first seek help. Veterans prize good ritual. Know the rites of your tradition; the Rite of Reconciliation, the Rite of Confession and Forgiveness and the Rites for Healing. Memorize your elevator talk for the rite of reconciliation (individual confession and forgiveness) and the rite of healing. They can be life-giving for many vets and even life-saving for others. What Confidants need to know about Post-traumatic Stress? In addition to fear, shame and guilt caused by transgressions and the events of war, veterans are likely to be struggling with other issues at the same time. When a veteran seeks you out, she is most likely wrestling with co-occurring problems. Common issues that co-occur are: depression, transgressions, grief, substance abuse and post-traumatic stress. The most common issue is post-traumatic stress (PTS), and the key symptoms of PTS are heightened reactivity, anxiety, fear, grief, anger, loss of memory, confusion, powerlessness, vulnerability and disconnection. Be aware that the veteran who comes to you for help is probably struggling with symptoms of PTS. Confidants need to have some basic understanding of PTS in particular in order to help vets. Confidants who have a basic grasp of PTS will: Immediately increase their capacity to help Reduce chances of doing harm Increase their sense of compassion satisfaction (vs. compassion fatigue) Increase their own capacities to care for themselves, their colleagues and their congregants So, let’s begin. Even moderately severe post trauma symptoms of confusion, loss of memory, anger, anxiety, etc., can leave one feeling profoundly vulnerable and unsafe in one’s own skin. It takes a lot of courage for a veteran to seek help when feeling extremely vulnerable because the brain isn’t functioning like it used to and the chemistry is raging. Many clergy have been taught to refer anything connected with the “T” (trauma) word. So, many clergy are themselves afraid of engaging veterans for fear of doing the wrong thing and triggering a flashback. Don’t give yourself a shame attack if you are talking with a veteran and he over-reacts, becomes terrified or dissociates. Let’s dig right into the fears. Dissociation, a common post-trauma symptom, is a more extreme form of disconnection. It’s a safety mechanism – akin to the freeze response. Most of us have been taught fight and flight. But, in between there is freeze and submit. Learn to recognize dissociation. Good signs that dissociation is occurring are: a vacant look in the eyes, the down-turning of the head, the palpable sense that the person has vacated their body and is not present. Prior to dissociating a person may feel the need to get up and get out. When that happens, let her go – she needs to. These symptoms correspond to changes in the brain / body chemistry and affect one’s ability to function. I know one soldier who describes his severe posttrauma symptoms as a double amputation of the brain. This graphic description helps people visualize the extent of the invisible wound and understand that, just as a person is incapacitated by having their legs or arms blown off, they are functionally incapacitated by severe post-traumatic symptoms. When experiencing certain symptoms at a high level of severity you literally can’t put one foot in front of the other. It’s like you have no legs. Your decision-making and meaning-making is incapacitated. Cerebral cortex functioning is severely undermined. Veterans struggling with post-traumatic stress are also extremely stress-sensitive. For example, when a veteran is highly anxious, it doesn’t take much additional stress to put him over the top. Veterans struggling with post-traumatic stress injuries experience heightened emotional reactivity on the high end and / or extreme numbing of emotions and perceptions on the low end. It is important for confidants to remember that normal for veterans struggling with more severe post-traumatic stress is often a constant state of high alert. And, when high alert is your new normal it doesn’t take much to put you over the top. Most people can at least appreciate and relate somewhat. When a “normal” person is overwhelmed almost anyone will either numb out or over-react on occasion. Now, multiply that X 100. Imagine feeling that way all the time and you can begin to appreciate the challenges veterans face when struggling with symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Post-traumatic stress reactions are easily triggered by conscious or unconscious perceptions related to the original traumatic event; the sound of fire-crackers can mimic the sound of gunfire, the backfiring of a car resembles the sound of an explosion, driving through an underpass or seeing something unusual on the side of the road instantaneously recall life-threatening situations. There are thousands of triggers and they are highly individual. A person in therapy suddenly had a flashback in group. He went to the floor in a fetal position. Later, he realized that the almost imperceptible hissing sound of the radiator in the background triggered the memory of the hissing sound of a chest wound of a buddy who died in his arms. Because these extreme reactions can be triggered days, weeks, months or even years after the precipitating event(s) they are labeled post trauma. Judith Hermann, in her ground-breaking book Trauma and Recovery underlines the importance of establishing safety and trust for healing and recovery to occur. The relation to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs immediately comes to mind. You need to establish a sense of safety before you can tell your story. Amidst clusters of symptoms that affect brain function and chemistry, Bessel van der Kolk, another leading expert in post trauma, insists that the basic goal of therapy is learning to calm the chemistry so that brain function and capacity can be restored. As a veteran learns to calm the chemistry she begins to feel safer in her own skin. As calming and soothing skills are anchored, self-confidence and perceptions of personal safety correspondingly increase. Having the veteran tell the story before a basic sense of safety and self-confidence has been established can undermine recovery and the benefits of confessional conversation. How Safe does a Veteran need to feel to engage in Confessional Conversation? Answer: safe enough. Safe enough means that a veteran doesn’t get so overwhelmed, terrified or dissociated that he can’t function when engaging in confessional conversation. Extreme post-traumatic stress reactions severely compromise the sense of safety and trust and undermine the benefits of any pastoral conversation. When a veteran over-reacts, don’t be afraid or feel that you have done something wrong. If this happens in your presence be assured it is also happening in other contexts. But, when it happens in your presence – it’s a good thing because, now you are in a position to support and assist – to do something constructive. Sidebar: First Responder protocol provides a good framework for addressing severe PTS and other spiritual—mental health challenges veterans face. The framework is as follows: 1. Assess 2. Treat and stabilize 3. Orchestrate definitive care When a veteran first seeks you out – consider yourself a first responder. The Parable of the Good Samaritan is a great text to use to teach the entire congregation about PTS and First Responder protocol. It’s all there in Luke 10:25ff. (see Congregational Teaching Tool) A chaplain was giving a talk to a group of trauma survivors in a relapse (substance abuse) program. It had been simply announced that the chaplain was going to give a talk on spirituality. Unbeknown to the chaplain, most of the group had suffered spiritual abuse either from their church, their clergy or Alcoholics Anonymous. Because of the relapse history and multiple unsuccessful treatment attempts, many had been humiliated and shamed as being unspiritual. When the chaplain entered the room he introduced himself and announced spirituality as the topic. At the mere mention of the word spirituality the lights went out, all heads bowed down and entire group immediately dissociated en masse. At first the chaplain didn’t know what was going on, and he cut a comical figure as he bent over trying to establish eye contact with anyone in the group. A co-therapist in the room saw what was happening and immediately started talking to the chaplain about another topic. As they conversed people gradually started returning to the room and heads started popping back up. About ten to fifteen minutes later, after the group’s chemistry had been sufficiently calmed they were able to ask, “What happened when the chaplain mentioned the word spirituality?” People in the group started talking about it and the experience turned into a wonderful teaching moment. Here’s another example. A couple was sitting on a porch with a Vietnam vet when a passing car backfired. Instantly, the vet leapt off the porch into the bushes and flattened out on the ground. When he realized what had happened he climbed back on the porch and said sheepishly, “I guess I’ve got some explaining to do.” Dissociation is a normal, common experience for veterans and other trauma survivors. Welcome to their world! When a veteran gets overwhelmed, terrified and dissociates in your presence it’s highly likely that dissociation is happening at other times and places. Don’t freak out yourself. Remember, it’s a good thing that these symptoms are happening in your presence because you are in a position to appreciate what’s happening: to assess and offer immediate support. If you need to offer immediate support, some basic re-grounding techniques will help. Think about the above examples. The Vietnam veteran who jumped off the porch already had a basic understanding of his reactions and was able to explain them to the couple. What would be your assessment? Answer: has a basic ability to self-soothe. What would be the treatment required? Answer: just listen. That’s the easy one. The other is harder because they would benefit by some good intervention. What you are trying to avoid is having the person leave your presence in a dissociated or overly discombobulated state. So, you need to try to help re-ground them. The following are some basic re-grounding strategies: Change the subject. “I can see that you’re getting really upset, charged up, having a hard time with this etc. Let’s focus on something else for a while. We can come back to this topic later when you want.” And then directly initiate another topic. When in doubt talk about the weather. Change the focus to the body. Have the person to rub their forearm, neck or upper arm. Focusing on the sense of touch in the present moment can help a person reground. Change posture: Have a person stand up. Some slow stretching and bending will help. Change the venue. Say, “Let’s go outside and get some fresh air.” Or say, “Let’s go for a walk.” Then talk about the weather and direct the person’s attention to the natural surroundings until they are re-grounded. If you know the person well and trust is higher you could say, “Hey, take a walk around the block as many times as you need to – and, then let’s continue.” When you deploy any of these strategies speak calmly and directly in a pastoral tone. The prosodic, pastoral tone of voice itself can help a person reground. (Think, calm, non-anxious presence) If a veteran is able to get substantially re-grounded with some assistance (i.e. restoration and improvement of affect, ability to converse, ability to smile or laugh) what would be your assessment? Answer: able to re-ground with some coaching. This kind of a person would benefit from skill building with a good therapist. Attempt to motivate the person to seek help from a therapist so the veteran can get some tools for their tool box. After a person has been re-grounded it can be helpful to: Validate the person and the experience. You could say, “That’s pretty intense (scary) stuff.” Then normalize the event and say something like, “These kinds of reactions are common, normal responses to traumatic events.” Emphasize the importance of learning how to ground and re-ground one’s-self. Later, you could ask, “When stuff like this happens do you have some tools and shortcuts to get yourself back on track?” If he hesitates or, if the answer is ‘no’ it can be helpful to immediately add a dose of motivation. You could say something like, “SOS + SOS = SOS. And, when they give you a confused look, explain, “Same Old Shit + Same Old Shit = Same Old Shit.” When a veteran doesn’t have a basic understanding of their over-reactions your assessment should be that they need referral to a competent therapist. Attempt to motivate the veteran to receive counseling. (See Motivational Interviewing) When possible, offer two good options and let the veteran choose. But, be sure that the therapists you refer to are collaborators who appreciate your work and have the wisdom and skill to either involve you or re-refer back to you for continued pastoral care and long-term congregational care. When a veteran seeks help from a clergy for the first time, err on the assumption that anxiety is very high. Even when a veteran presents a cool exterior remember that all soldiers trained for the current combat environment are trained to mask fear and present a pleasant face to the public while, at the same time, figuring out five different ways to kill a potential enemy. So, take time to reduce anxiety. Don’t rush. Take time to calm yourself – and move from busy schedule to calmer presence mode. Deploy the social conventions that help everyone relax, feel safer and enjoy the moment. Engage in some chit-chat. Have beverages available, water and hot water for tea, apple cider, hot chocolate, or coffee. Use a little judicious humor. What you are doing is creating perceptions of safety and establishing trust – or what therapists sometimes call the therapeutic alliance. With some vets this can happen very quickly. With others it can take time. Sometimes the best first session with a vet is simply chit-chat – getting to know each other, figuring out the dance, testing the waters and slowly generating the safety and trust that will bear the burden of more serious work. Trust in the Confidant increases perceptions of safety. Salve, the Latin root of salvation is reflected in the word salve, a soothing ointment. And trust is a synonym for faith. This is the church’s bread and butter. We should be experts at helping people experience trust and safety. The pastor / confidant’s mantra is: safe places, safe processes, and safe people. Who is the expert on safety and trust? The answer: the individual veteran. Pay attention to your veteran and she will teach you what safety and trust is for her. Again, clergy are a known entity to the veteran and his / her family. The priest may have known that family for years and already walked with family members through life passages, trials and tribulations. When a veteran seeks pastoral help from you, it is safe to assume at least a minimal level of trust and a huge amount of courage on the part of the veteran. The confidant’s job is to build on that trust by increasing perceptions of safety. In building safety and trust with veterans remember this as a primary guideline: the individual service member knows what her safety needs are. For example, she knows where she needs to sit in order to feel safe, and she knows what she can tolerate in any given session. She is the authoritative expert on her safety. She knows if she wants another person or pet to accompany and support her. Whenever you can, let the veteran know that she is in charge. A common way to do this is giving options. Offering options will help establish the veteran as a locus of power and control. Amidst the assaults of symptoms that leave one feeling profoundly vulnerable, powerless and out of control – even simple choices can be life-giving. Pay attention to your language. Place a premium on the language of choice rather than command. Now, for some soldiers (think Marines), the commanding voice of the First Sergeant, may actually be perceived as the soothing tone which is called for. But, before deploying First Sergeant Style it is usually advisable to wait until a level of trust and safety has first been established. Sidebar: Use your pastoral judgment on this. If you think the person will see you as wishy-washy or milquetoast – become directive and see how the veteran responds. You might be surprised. Sometimes you can say – and with a forceful First Sergeant tone, “Get your sorry ass into counseling before you hurt yourself or someone else!” Generally, when a person comes to see you, ask things like, “Where would you like to meet? I have an office that offers a lot of privacy. Or we could meet in the lounge, or any other place that works for you. Where would you prefer to meet?” When the veterans come into your office invite the person to sit wherever they’d like. If you have a healing chair (some clergy do) you can offer that as your preferred option – but give the veteran the choice. “Here’s the healing chair, but any chair will work. You pick.” Most veterans need an orientation to forgiveness. Even those experienced in the rites usually appreciate re-orientation from you when they are feeling confused and lost. A good hip-pocket orientation to the process of the rite of reconciliation (confession and forgiveness) can help put a soldier at ease. You can say something like the following, “Forgiveness is like a military mission that has two parts. The first part is confession. That’s where you tell your story – and especially the parts you feel you need forgiveness for. The second part is forgiveness. That’s where I pray to increase your faith and then pronounce God’s forgiveness. The forgiveness part doesn’t take very long – just a minute or two at the most. The first part, telling the story, can take longer, but confession itself doesn’t take very long. And the absolution (forgiveness) takes about a minute. And, you don’t worry about saying the right or wrong things. If things get a little intense, you can take a break any time you want. And, remember, everything you say is ironclad confidential.” Safety and trust need to be maintained through all phases of treatment and recovery. All confidants need to constantly place a premium on the language of choice. Get accustomed to saying things like “at your pace, when you decide, what you prefer, what works for you” – things like that. It’s empowering to veterans who regularly experience a sense of powerlessness to learn that they have choices amidst their vulnerability. Make Confession and Forgiveness a Mutual Mission Soldiers understand and resonate with the language of mission. If a veteran is seeking forgiveness – use mission focused language and directives. Veterans understand the importance of mutual trust in accomplishing a mission. You can say, “We’re on a mission together. Your part of the mission is to tell your story and confess the parts you need forgiveness for. And my part of the mission is to encourage faith and pronounce God’s forgiveness.” Part I – The Confession Listen to the story. Remember, she’s coming to you for assistance and you need to honor her agenda and her story. If things get too far off-track, a simple, gentle reminder of the mutually agreed-upon mission-focus will usually be enough to get a person back on track. As you listen, make a note the points of pain and the bruises of numbness. Veterans usually have a cluster of spiritual needs. Woven among confessional conversation are three things are always prevalent: grief (especially loss of faith), the need for forgiveness, and the need for belonging (i.e. positive reconnection with God, self and others). As a person tells their story you will hear plenty of lament. Always be prepared for snot, tears, anger and rage. Have plenty of tissues available. They are important symbols of comfort. As you listen to the story note the sharp points of guilt, shame, fear and hurt. Notice where the veteran is numb and what she avoids or embraces. Don’t judge. Simply tuck your observations, judgments and clever responses away and just listen. Imagine placing them all in a little brown paper bag and putting them on the shelf. Comfort yourself with the thought that, if necessary, you can always choose to retrieve them later. The, bring your focus back to the veteran and continue to respectfully listen. Remember, confession doesn’t need to be perfect. What may appear to you as a poor confession may be doing the trick. Remember, you aren’t the judge; God is. And, remember, that the primary goal of confession is to re-establish faith in the God who forgives. That faith is God’s gift, not yours. It is ultimately the increase in faith and trust in God that you want anyway. And, it is that trust that will motivate a person to return and continue their spiritual soul work. So, confessors also need to increase their faith and believe that God does work through his word and promise (Isaiah 55). A general guideline is not to push your agenda. Don’t do it – especially, if this is the first time you are hearing confession. This is the veteran’s time to present what she feels she needs to present – to God. Just feel privileged to be an instrument that God can use. So, be present and listen deeply. Because the common confession during worship is “things done and things left undone” veterans are inclined consider a narrower cluster of transgressions commonly known as sins of commission and sins of omission. These will usually be the perceptions that veterans bring into the rite of individual confession and forgiveness. Note that confession and forgiveness is more appropriate for transgressors, that is perpetrators, witnesses (those who usually have the power and ability to intervene but didn’t), and those who have betrayed others. For example, an intentional, malicious command decision that puts a soldier (or soldiers) unnecessarily at risk is King David. Remember his affair with Bath-Sheba (what today would likely be considered sexual assault – given the circumstances and power differential) and his subsequent attempt at cover-up by using his command authority to kill Bathsheba’s husband Uriah by sending him to the front line of battle where he would surely die (2 Samuel 11:14&15). As we eaves-drop on David’s personal confession and absolution by Nathan in 2 Samuel 2:13 we learn the basics of confession and forgiveness. In 2 Samuel 2:13 David finally hits bottom and, when that happens, Nathan immediately forgives. What about False Guilt? It is not uncommon for victims of abuse to assume guilt for sins perpetrated against them (i.e. sexual assault). In most of these circumstances rites of healing and release from the heavy burdens, oppression and consequences of the transgressions of others are appropriate. Release (escape) from the oppressive burden of the sins perpetrated by others is the goal of pastoral care. And, in these circumstances, the rites of healing and release from oppression and oppressors are most appropriate. Remember, when the Israelites were experiencing abuse and oppression under Pharaoh God didn’t instruct Moses to forgive Pharaoh. He said, “Tell Pharaoh, let my people go!” However, a word of caution. I know of a commander who had a soldier in his command who complained to his platoon sergeant of a back problem. The platoon sergeant ordered the soldier to go for a medical exam. After the exam the soldier was given medication and ordered to perform light duty until he was pronounced fit for duty by the doc. Not long after he returned to duty, the platoon was involved in a firefight and the soldier ended up twisting his back. He was medevac’d and was later diagnosed with a severe injury to his vertebrae that would affect him for the rest of his life. His battalion commander, not the platoon sergeant, felt guilty. The Battalion CO was Roman Catholic and approached the Catholic Chaplain for absolution. When the Chaplain started to offer counsel about false guilt, and saying that it really wasn’t his fault, the commander interrupted him and said he didn’t want to hear that shit and demanded absolution. The Chaplain wisely pronounced absolution, and the commander experienced immediate relief from the burden of what appeared to be false guilt to the Chaplain. In war there is often guilt by association – especially for those in command who have been charged with looking out and caring for the well-being of their soldiers. If the confessor is going to err, always err on the side of mercy and forgiveness. Pronounce it. But remember that rites of healing are more appropriately worded for victims of perpetration and betrayal. So, know your rites. (See Rites of Healing Ministry) The Confession After the story has been told, the Confessor (confidant) can ask the penitent in the traditional way, “Are you ready to make your confession?” Most who are new to confession may need a simple directive, “You are ready to make your confession. What are the things that bother you that you want to confess?” An invitation to trust in God can strengthens the therapeutic alliance between the penitent and God. Before pronouncing absolution it is customary to encourage faith in this alliance. Because a person has usually not been exercising faith – the invitation to trust in God can feel new, different and even downright awkward. A word that encourages faith can be very helpful. Some veterans simply need permission to move past the awkwardness and re-affirm their trust in the forgiveness of sins. You can say something like, “Remember, it’s OK to believe that God forgives your sins.” At other times you might say, “Do you believe that God has that power and authority to forgive your sins?” Sometimes, a person needs to be reminded, “Remember, my pronouncement of forgiveness are the very words Christ speaks to you. Do you believe that?” Sometimes, something simple prayer like the following may be said before absolution: God be gracious to you and strengthen your faith. Amen. One of Jesus’ favorite nicknames for the disciples as a group was “little faiths”. Remember, even a mustard seed faith, can make a big difference. And, the promise of forgiveness, pronounced by you, in and of itself has the power to create the faith necessary to move the mountains of fear, guilt and shame. Be ready to pronounce forgiveness with confidence. It’s good to have a simple formula memorized, so that if and when you are under extreme duress it will be readily accessible. Then, in keeping with mission orientation it can be helpful to say, “Now, we are done with the first part of the mission, which is your confession and we go to the second part of the mission which is forgiveness. Note: The priest in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox or Anglican tradition will use the word absolve in the formula. However, if the confessor is a clergy or confidant from a tradition other than Roman Catholic, Orthodox or Anglican and your veteran (the penitent) comes from a Roman Catholic, Orthodox, or Anglican background, always use the term forgiveness rather than absolution. Using the word forgiveness will reduce the potential for confusion for veterans who come from traditions that teach that absolution can only be pronounced by the priest. A shift in posture or a change in garb can be helpful in emphasizing the shift in mission and accentuate the move from confession to absolution. If a person has been sitting invite them to kneel or stand. Putting on the stole, a symbol of authority, may be useful during the entire rite, but can emphasize the magisterial shift of God’s pronouncement. When anointing with oil, make the sign of the cross at the traditional moment, when the name of +Jesus is invoked. Part II – The Forgiveness (Absolution) The following are some traditional formulas for forgiveness and absolution. The words in bold italics are the heart of forgiveness and need to be pronounced. At the end of the formula you will notice that amen is underlined. The amen is underlined because it is the ‘yes’ of faith uttered by both the veteran and the confidant. It is not uncommon for the veteran to say ‘thank you’ and smile after receiving forgiveness. This too can be a response of faith. Sometimes a person becomes very tearful. Be open to a vast variety of expression following absolution (forgiveness). I. I, by the command and with the authority of the Lord Jesus Christ, forgive you your sin in the name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. (Mk 5:34; Lk 7:50; Lk 8:48 Luther’s Small Catechism can be administered privately by a pastor or layperson.) II. Our Lord Jesus Christ, who has left power to his Church to absolve all sinners who truly repent and believe in him, of his great mercy forgive you all your offences: And by his authority committed to me, I absolve you from all thy sins, In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen (Book of Common Prayer – Reconciliation of a Penitent – priest absolution formula) III. Our Lord Jesus Christ, who offered himself to be sacrificed for us to the Father, and who conferred power on his church to forgive sins, absolve you through my ministry by the grace of the Holy Spirit, and restore you in the perfect peace of the Church. Amen. (BCP – priest formula) IV. Our Lord Jesus Christ, who offered himself to be sacrificed for us to the Father, forgives your sins by the grace of the Holy Spirit. Amen. (to be used by a Deacon or Layperson) The rite concludes: Go in peace. Brief pastoral conversation may follow. The emphasis here is brief. You want the person to go away with the voice of the Good Shepherd primarily reverberating in their heart and mind – not yours. If the veteran asks about amends you need to use pastoral judgment. Of course, listen to what the person says. Often the amends represent an appropriate response of gratitude to God. Zacchaeus is a good example of appropriate amends springing from the gratitude of a newfound freedom. But, many people, hearing God’s free pardon, want to go back into the comforts of the old penal system and reflexively want to punish themselves by imposing a sentence (or penance) on themselves. Some pastoral conversation may be helpful. If the veteran’s move is a return to the prison they’ve just been freed from – point it out… and ask, “Why do you want to impose a sentence of yourself, after you’ve just been pardoned” Then listen. If the person hesitates – consider saying something like, “Sometimes there’s something that a person discovers they still need to talk about. Sometimes it can seem like a little thing. But, it isn’t. Sometimes it’s a real blockbuster. If so, you have a choice – to talk about it now or at another time. Remember, God can take it – and forgive. And, I’ve got nothing but time. Your choice.” Over time and with experience you’ll get a pretty good intuition whether or not this is the typical knee-jerk return to the comforts of the old prison, or whether something else pressing on the veteran. Typically, it is things that have potential legal consequences that cause a person to balk: stealing, sexual assault, atrocities, war crimes, murder – things like that. But, sometimes it is something simple, for example, stealing some money from a buddy. Offer options – but give God’s preferred option that now is the acceptable time. It can be helpful to say that making amends is another mission, and now is the time to just go home. Amends tend to spring naturally from the new freedom of forgiveness. And, it can take time, discernment and wisdom for amends to crystallize. But, don’t be surprised or offended if the veteran starts making amends in spite of your guidance. Notes: 1. Encouraging faith is sometimes referred to as calling out faith. Faith is what receives the pronounced promise of forgiveness. Encouragement helps prepare faith to be at-the-ready and strengthens the therapeutic alliance. This is like cleaning the contacts of the battery for a stronger connection with and reception of the pronouncement of God’s word of forgiveness. 2. The benefits of confession are appropriated by faith in Christ. So, remember, it is not just the recitation of misdeeds and burdens that’s important. But, rather the simple confession of faith, the quiet yes of trust that is most important. The yes (amen) spoken at the end of the pronouncement is also a simple confession of faith. Remember, faith in God is what the troubled conscience has lost and trust in God is what is being restored in confession and forgiveness. When the confessor pronounces forgiveness, the confessor is saying in effect, “The word and promise I pronounce are the words and promise of the Good Shepherd. And, from now on this is the voice that you get to pay attention to – not the voices (inner and outer) that blame and shame. From now on you listen to the voice that pronounces forgiveness and healing – nothing else. 3. Notice that forgiveness is conveyed best in the form of pronouncement, not prayer. What is the direction of prayer? Prayer comes from us and is directed to God. What is the direction of pronouncement? Pronouncement of forgiveness comes from God, through the confidant and is directed to the veteran. The confessor doesn’t pray for forgiveness, she pronounces it. The pronouncement of forgiveness is a very special moment because it comes directly from Christ who speaks through the confessor with Christ’s authority, to the veteran. We don’t pray for forgiveness. We pronounce it. Pronounce forgiveness with confidence. It helps to have a formula for individual forgiveness memorized. 4. Of course confession and forgiveness can and must be repeated. If a confidant is providing long term care for the veteran. Instruct the veteran to call the confidant every day for the first two weeks and have the confidant remind, and re-peat the pronouncement. This will help anchor faith more firmly. 5. Veterans with even mild post trauma will experience symptoms of confusion and memory loss. The briefer and simpler the rite and especially the words of forgiveness the better. One could simply say, “By Christ’s authority and command, I forgive you. “ Write out the words of forgiveness and invite the veteran to put them in a prominent place as a reminder and reassurance of forgiveness.