SPEECHES - Mater Academy Lakes High School

advertisement

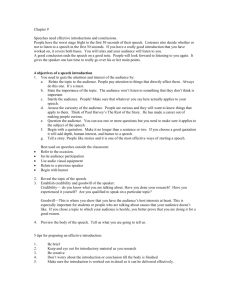

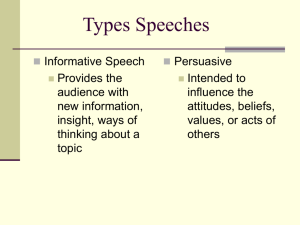

SPEECHES INTRODUCTIONS Thinking that opening with a joke is a good idea is a common misconception in speechwriting; it is not the way to an audience's good graces and rapt attention. Don't get me wrong - I'm the greatest proponent of oratorical humor you'll ever find! However, the use of humor demands more care than a single punchline cut-and-pasted at the beginning, especially since such jokes tend to not fit. All too often, introductory jokes clash with a speech which turns dry and conspicuously humorless post-punchline. Read on for some intro tips to keep 'em listening like no one-liner ever could.... The Introductory Scenario - Jokes are out, but stories, original stories, are undoubtedly in. Whereas a joke that fits a speech well is quite a rarity, humorous, intriguing, and appropriate tales can be tailored for any occasion. Of course, this is option is great for anyone who wants to let the laughs roll - an uproarious story beats a one-liner any day. And it's especially effective when it's wrapped around the speech - that is, write your scenario with two parts, one serving as the introduction to the speech and the other as the ending. It provides a level of continuity and closure in the speech that's tough to meet with other methods. Check Rally 'Round Raleigh and CyberLife (both in the "Samples" section) for examples of the intro/closing scenario; they each use a humorous second-person narrative in this manner. The Reality Check - An audience subconsciously expects certain things from any speaker; for example, the speaker is expected to give a practiced, relatively inflexible and detached performance. They expect the speaker to be delivering lines rather than actually speaking with the audience; they expect an acted script instead of reality. The result: it's verrry easy to mess with people by not conforming to these expectations! Start with conversation with the audience; step down from the spotlight and do the speech while sitting with the people... do anything that makes people wonder, "Is this a speech or is this guy being real???" (Hence, the reality check.) The most effective use of this introduction I've seen was a competitive original oratory where the speaker pretended - very believably - that she had forgotten the introduction to her speech. Coupled with expertly feigned embarrassment and emotional distress, this routine never failed to dupe the audience. On several occasions, judges even stopped the round and asked if she needed "some time to collect herself!" Nonverbal Openings - These are often the most attention-grabbing introductions; since an audience will always expect a speaker to at least speak, a verbal silence inevitably draws the audience to whatever else you are doing! I've seen people start speeches in pantomime, by mutely straightening the clothing of an audience member (it was a speech on superficiality), by moving their lips without sound (a speech on deafness), and by shooting the audience with a ping-pong-ball gun (a speech on violence, done by my father in high school). Be careful with the use of nonverbal openings, though - if what you do doesn't work with the content of your speech, it's at very high risk of seeming like a gag or a stunt. Also, be aware of your audience; from what I heard, the shooting-the-audience bit didn't go over well with teachers and the toy gun was confiscated. Other than that, go nuts the more creative and unexpected, the better! Of course, for all the good ways there are to intro a speech, there are just as many BAD ways. Let's check some of those out : If you don't like any of the introductions described on the previous page, don't sweat it; they're not for everyone, and certainly not for every speech. However, I would be remiss if I didn't keep you from succumbing to the oh-so-trite "conventional" intros which too often are the easy route for lazy speechwriters. There are several such intros to avoid besides the opening joke one-liner previously discussed... but let me hit that one again: don't open with a lame, half-assed, lowest-common-denominator punchline! Good. Now here are the others to avoid at all costs: The Opening Quote - It's a standard these days: people think they can start a speech smoothly (while simultaneously making themselves look educated) by quoting some old/distinguished/famous person on the subject. Sorry, but unless it's a really good quote with amazing following material, it's just going to bury you even deeper. Think about it - when was the last time you were captivated by a speech that opened with "I believe it was John Q. Someguy who once said..." A Story about Writing the Speech - This is the crutch of those who are really uncomfortable with public performances. The whole "last night I was thinking about what to say to you on the subject of ____, when..." just doesn't cut it in most cases. On the other hand, if something truly extraordinary and spellbindingly interesting did happen to you while in the process of speechwriting... well, be my guest! The Dictionary Definition - Never never never, ever ever ever. In fact, if a quote from Webster's occurs anywhere in your speech (unless there are some remarkable extenuating circumstances), you need to rethink it. The answer is no. CONTENT Now that your intro's over and you've done all you can to entice your audience to stay with you, you've gotta make them glad they did. A speech that starts with a bang but ends with a whimper is still remembered as a bad speech! So we're going to cut the writing of the speech body into two parts: this part, Content, is concerned with constructing your message, or "thesis" if you prefer, and the manner in which you plan to convey it. After that, check out Devices (at left) for some ways to dress the speech up and make it interesting. Okay, the steps: Goals - It's best to start with some objective in mind. Are you entertaining, educating, reminiscing, narrating, persuading, or any combination of these or other goals? No matter how much you dress up the speech, make sure that it doesn't stray too far from its intention. And one recommendation: entertainment should almost always be included with whatever other goals you've got. An unentertained audience is a sleeping one. But I digress; got goals? Good. Go on... Views - Who are you speaking to? Whose views do you want to present on your subject? (And note that the incorporation of views other than the obvious often make for an interesting speech... more on that in Devices.) Especially in persuasive speeches, which many many speeches are, multiple viewpoints are very effective. Point/counterpoint is even more compelling in speeches than on paper, in fact! "Points" - You know it & I know it: from the very beginning, there are some things (I call'em points) that you just need to include in the speech. Maybe because the nature of the speech requires it, maybe because you just know you have to include this a bit that you love - whatever the reason, don't ignore these points! Write them down, think about how they relate to each other and to the speech as a whole; this is the beginning of an outline... Flow - Now we need to put what we've got together into something coherent. Incorporate the views and points while satisfying the goals. However, a speech that flows needs more than just the right parts - it needs some kind of development, some variation throughout, to create an interesting and effective presentation. Try presenting opposing viewpoints at first and moving gradually, through the introduction of various pieces of evidence, to your conclusion at the end. Try starting with only questions, and lead the audience on a "path of discovery." Whatever you do, keep this as a rough outline for now; it needs more fleshing before it's a viable piece of oratory. Attitude - This is also a good time to do a 'tude check, and make sure you're not only conveying the message you want, but also the mood. As I've said before, sarcasm is perfectly fine (in fact, recommended) in small doses, but too much can render the speech depressing and cynical, and the speaker someone the audience loves to hate. It's very rare that a speech will want to have a negative outlook; keep the downsides balanced by plenty of upside. And don't confuse humor with a good attitude; a lot of humor is actually negative in this context! DEVICES At this point, you should know what you're going to say - you've got the message of the speech pinned, and you've got a nice outline of ideas, items (research or quotes, for example), and views that you want to include. But the speech isn't written yet, oh no! It's amazing how little the actual content of the speech does to keep an audience's attention. In that light, there are quite a few devices that can be used to intrigue the audience, shock and amuse them, keep them thinking about you and your speech, but most of all just keep them interested! Unconventional Treatment - An audience usually thinks it knows what it's getting into. If they're going to hear a speech about some charitable cause, they expect to be persuaded that the cause is grand and its effects far-reaching. If it's a reunion speech, they expect fond memories & humorous happenings of times past. If the speech is at all educational, they expect to be presented with a straight-forward declaration of facts, causes, and effects. Borrrrring! Do something they aren't expecting. Satire works very well here - if anyone's read Jonathan Swift's A Modest Proposal, you know what I mean. Convince people of some idea by (for example) speaking straight-faced about the obviously ridiculous opposite! Use stories and fantasy to tell about scientific facts, thus improving educational speeches. Conversely, use "scientific facts" to tell about stories - especially useful for reunion speeches and the like. Why all these bizarre recommendations? Because by definition, my dear readers, "conventional" treatments have been worn out already! Characterization - Too often, hearing one person talk for any significant amount of time is not a lot of fun. One person has one voice, on mannerism, one style of prose; it just gets dull, even a bit lonely! The obvious solution: characters! If you have extra "people" in the performance, the variety of and interaction between them creates a more dynamic (and as a bonus, more entertaining and memorable) presentation than a mere soliloquy. Be careful not to cross the line into a disturbing simulated schizophrenia; make effective but discrete use of the characters. Having them recur in the speech can also be a nice touch - people become familiar with them and their particular viewpoints, which enables the efficient presentation of a greater variety of views on your subject. All that said, it's a good thing to try and I, for one, think it's a lotta fun! Narrative - Kind of a supplement to characterization device, and just like the scenario/narrative introduction previously mentioned. It works; people naturally follow spoken narratives better than spoken persuasive ideological abstractions. It clearly demonstrates the causal relationship (if any) in your material, while keeping the audience duly entertained. Give it a shot sometime; you shan't be disappointed. "Applause Points" - It's helpful to plan in advance the reaction of an audience; most specifically, when they will react strongly with laughter or (depending upon the situation) applause, quiet consideration, etc. I call any moment where the audience reacts strongly enough to be considered in the speech an "applause point." It's a good idea to arrange these points regularly throughout the speech - if it goes too long without one, you may lose the audience. Mix them up - laughter here, a pause for thought there - and leave time for the audience to use them. But remember that applause points don't always work as planned - it's a good idea to test them, in the context of the entire speech, with a friend, teacher, or family member first. Dashes - Okay, let's talk "speakable prose" versus "readable prose." In readable prose, it's bad form to use a lot of dashes and semicolons, and you can't start sentences with "and" or "but." Not so with speech! In speaking, one very often wants to relate a sentence or clause with the preceding one, to form an audible progression in thought - such inflection-communicated associations are best expressed in the transcript through the use of dashes and semicolons. (Note the use of the dash between those two sentences; speak the combination aloud and you'll see how it works!) "And" and "but" are useful when you want to let an idea sink in with a pause and subsequently add to it (or contradict it) without losing it. It works. Look at all the times I've started sentences with these words in this guide; say them out loud and see how they work! TIPS It is indeed the number one fear of American adults: speaking before an audience of peers. Incidentally, I seem to remember it's number two for teens, right after parental divorce. Well anyway, there's no need to be afraid of speaking before peers - or, for that matter, superiors, students, friends, infants, pets, or a mirror. I recommend those last three for practice, by the way. So let's get to it - some performance tips for your speech... Know Your Place - Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that you belong in front of an audience giving a speech. That is, unless you're doing a walk-on. But seriously, the audience expects you to give a speech - they're not going to question why you're up there shooting your mouth off! This is meant to make you comfortable with public speaking, but to be completely honest, the best way to get comfy with speaking is practice. If you ever get a chance to do small & easy bits of public speaking - announcements, church readings, etc - take it. It'll help. Rehearse - Run the speech past some people you trust (family, friends, whoever's having you do the speech, etc.) just to get a feeling for their reactions. You'll be more sure of yourself when you find out they don't hate the speech; it always works for me! That, and you get the bonus of a little feedback - you discover some parts that don't work (no speech is perfect) and fix'em in time for the real audience. You'll find out if those "applause points" (see Devices) work out the way you planned. Of course, if you don't want to go straight to sentient beings for practice, try it with pets or babies - these are better than sofas or walls because you can also practice eye contact... Eye Contact - If you're not paying attention to them, they're not paying attention to you. Vary your eye contact about the audience, changing people as your prose suggests - for example, stay with the same person through the end of a phrase or sentence, then switch. Especially in competitive speech, eye contact is a very important criterion for judging; practice it, make it natural. You'll be glad you did. Inflection - Every inexperienced speaker runs the risk of a monotonous speaking voice. Just remember that you need to exaggerate all inflection while on stage - you need more emphasis to get the tone of your speaking across to a larger audience. Don't overdo it and overact, though; sincerity is a delicate and precious aspect of any presentation. Practice will help you strike the balance! Gestures - A touchy part of any speech; you want to make sure that you're neither rigid nor dizzying, as either detracts significantly from the presentation. Practice, practice, practice - you should have some idea of what kind of thing you're doing to accompany each segment of the speech, but knowing exactly what you're doing conveys a yucky plastic artificial quality that nobody wants to see. Vary gestures from practice to practice, performance to performance... it'll keep you on your toes, and that keeps the audience interested. As I said in the "Delivery Tips" section, public speaking is the number one fear of American adults! I know that I, or anyone else, can tell you why it shouldn't be - but I also know that telling you that won't make it any easier... So here's the REAL trick: It's not about not being nervous. It's about not looking nervous. Seriously! I've been doing various forms of public speaking for almost a decade now, and I'm still nervous every single time. You just learn to control it - or even better, use that nervous energy to help you! With that energy, you can add more oomph to your speech - more enthusiasm, more spunk. The audience loves that stuff. But there are other tricks to calm the nerves before getting up there for the big show. Here are a few you may want to try: Know Your Place - I said this in the previous section, but really think about it. You're supposed to be up there giving a speech. You're not doing something weird, bold, risky, or stupid - you're supposed to be doing it! Remember that - you'll feel better. Rehearse - I said this in the previous section, too, and it's still true! The more comfortable you are with your speech in private, the easier it is to transition to public. Think of the nervousness as having various contributing factors: part of it is because of the stress of talking in front of people, and part of it is because of the stress of doing the speech right. Rehearsal in private takes care of that second part better than anything else, and rehearsal in public helps both! Breathe! - You need air to speak, but you'd be amazed to see how many people try to deliver presentations on quick and shallow breaths. Breathe. Normally. Ahhhhh. Slow Down - Many nervous speakers tend to speed up. This can complicate things quickly - namely, neither your mouth or your brain can keep up. When your mouth can't keep up, you trip over your tongue, and that's never fun - speakers can get flustered and become a nasty oratorical train wreck. When your brain can't keep up, you run out of words to say - and your mouth starts using fillers like "um" and "uh," which never sound too good. Slooooow is goooooood.