Causation in fact

advertisement

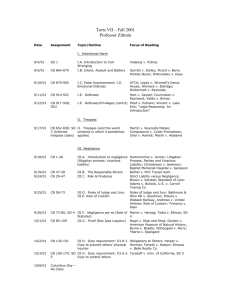

TORTS Remoteness and Damage [1] GENERAL:CAUSATION Duty of Care breach causation damage = Negligence There must be a causal link between D’s breach of duty and damage to P or P’s property Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Morts Dock and Engineering Co Ltd (The Wagon Mound 1) • The facts: • The rule: the replacement of ‘direct’ cause (Re Polemis )with reasonably foreseeable’ • It is not the hindsight of a fool, but the foresight of a reasonable man which alone can determine liability (per Viscount Simonds) CAUSATION: THE ELEMENTS • Causation involves two fundamental questions: – the factual question whether D’s act in fact caused P’s damage: causation-in-fact – Whether, and to what extent D should be held responsible for the consequences of his conduct: legal causation CLA s5D • (1) A determination that negligence caused particular harm comprises the following elements: – (a) that the negligence was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm ( "factual causation" ), and – (b) that it is appropriate for the scope of the negligent person’s liability to extend to the harm so caused (scope of liability" ). • (4) For the purpose of determining the scope of liability, the court is to consider (amongst other relevant things) whether or not and why responsibility for the harm should be imposed on the negligent party. THE ELEMENTS OF CAUSATION Causation Factual (Causation in fact) Legal CAUSATION-IN-FACT • Causation in fact relates to the factor(s) or conditions which were causally relevant in producing the consequences • Whether a particular condition is sufficient to be causally relevant depends on whether it was a necessary condition for the occurrence of the damage • The necessary condition: causa sine qua non CAUSATION • To be successful in a claim for a remedy, P needs to prove that the loss for which he/she seeks compensation was caused in fact by the D’s wrongful act • Traditionally, the test whether D’s wrongful act did in fact cause the loss is the ‘but for’ test Kavanagh v Akhtar • Facts:a Muslim woman who was physically injured while shopping was forced by the medical condition she had to then cut her previously long hair… Husband rejects her causing her to suffer depression – In any event, the possibility that a person will desert a partner who has been disfigured in the eyes of the deserter is sufficiently commonplace to be foreseeable (Per Mason J) • It was not necessary that the defendant should have foreseen the precise nature of the consequences of his act. In the present case, the plaintiff’s psychiatric illness was foreseeable Chapman v Hearse; Jolley V Sutton • The place of intervening acts in causation • Jolley v Suttton – P then aged 14, sustained serious spinal injuries in an accident. It arose when a small abandoned cabin cruiser, which had been left lying in the grounds of the block of flats, fell on Justin as he lay underneath it while attempting to repair and paint it. As a result he is now a paraplegic. – D held liable; what must have been foreseen is not the precise injury which occurred but injury of a given description. The foreseeability is not as to the particulars but the genus. MATERIAL CONTRIBTION • In general, it is not sufficient for a plaintiff to • show that the negligence was one of several possible causes; It needs to be demonstrated that D’s conduct was the most probable cause of P’s damage. In Common Law, it is also not enough for P to show that D’s conduct materially increased the risk to D. P needs to prove that D’s conduct materially caused the damage MATERIAL CONTRIBUTION • Bonnington Castings v Wardlaw [1956] AC 613 – The plaintiff had a lung disease because of fumes the employer had exposed him to, plus he had exposed himself to smoke – issue whether employer had caused the disease? – House of Lords held: P must make it appear at least that on the balance of probabilities the breach of duty caused or materially contributed to his injury MATERIAL CONTRIBUTION • Chappel v Hart (1998) 156 ALR 517 – Court noted that the Plaintiff must show the Defendant’s action materially contributed to the Plaintiff’s injury INCREASE IN MATEARIAL RISK • M’Ghee v National Coal Bd (1972) 3 All ER 1008 – The P claimed employer’s failure to provide showers to wash away residue caused his dermatitis - the doctors were not certain if showers would have stopped the plaintiff contracting dermatitis D held liable but mainly on policy grounds • Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority (1988): – a premature baby negligently received an excessive concentration of oxygen and suffered retrolental fibroplasia leading to blindness. However the medical evidence demonstrated that this can occur in premature babies who have not been given excessive oxygen, and there were four other distinct conditions which could also have been causative of the fibroplasia – M’Ghee distinguished on the grounds that there was only one causal candidate (brick dust) Bailey v The Ministry of Defence & Anor (2008) • The claimant aspirated her vomit leading to a cardiac • arrest that caused her to suffer hypoxic brain damage. There was evidence of negligence by the medical team the question: what caused her to aspirate her vomit. – Issue: whether the negligence had "caused or materially contributed to" the injury – Held: If the claimant could have established on the balance of probabilities that 'but for' the negligence of the defendant the injury would not have occurred, she would have been entitled to succeed. – The instant case involved cumulative causes acting so as to create a weakness so that she could not prevent the aspiration INCREASE IN MATERIAL RISK VERSUS MATERIAL CAUSATION • “A material increase in the risk of injury by a defendant is not legally equated with a material contribution to the injury by a defendant. However, in some circumstances if it were proved that the defendant did materially increase the risk of injuring the plaintiff then the court might infer causation, i.e. that the defendant’s negligence materially contributed to the injury (Wallaby Grip (BAE) Pty Ltd (in liq) v MacLeay Area Health Service ) Causation principles under the CLA: s5D (2) • In determining in an exceptional case, in accordance with established principles, whether negligence that cannot be established as a necessary condition of the occurrence of harm should be accepted as establishing factual causation, the court is to consider (amongst other relevant things) whether or not and why responsibility for the harm should be imposed on the negligent party MULTIPLE CAUSES • Where the injury or damage of which the plaintiff complains is caused by D’s act combined with some other act or event, D is liable for the whole of the loss where it is indivisible; where it is divisible, D is liable for the proportion that is attributable to him/her MULTIPLE CAUSES: TYPES • Concurrent sufficient causes – where two or more independent events cause the damage/loss to D ( eg, two separate fires destroy P’s property) • Successive sufficient causes • Baker v Willoughby; Faulkner v Keffalinos; – D2 is entitled to take P (the victim) as he finds him/her – Where D2 exacerbates a pre-existing loss/injury (such as hasten the death of P) D2 is liable only for the part of the damage that is attributable to him The Law of Torts Particular Duty Areas: Product Liability Abnormal Plaintiffs Unborn Children Liability for Defective Products: The Scope • Product liability as a regime for protecting consumer rights: – Defective structures/premises (as products?) – Consumer goods as products Product Liability: Evolution in Common Law • Originally in Common Law, a consumer in receipt of defective goods (including goods that caused injury to the consumer because of defects) was protected by the warranties implied in the contract of sale • The implied warranties was later incorporated into statutes: – Sale of goods Act 1983 (UK) – Sale of Gods At 1923 (NSW) The Difficulties with Implied Warranties • Warranties do not ‘run’ with goods. It is simply an • • element of the contract and does not therefore attach to the goods as such There is generally no ‘ vertical privity’ between the manufacturer and the ultimate consumer let alone between wholesalers and the ultimate consumers Privity of contract ‘remained a recalcitrant obstacle to the extension o warranties between the manufacturer and the ultimate consumer ‘ (Fleming) The Emergence of Negligence Law: Donoghue v Stevenson • The existence of the duty of care between the manufacturer and ultimate consumer • ‘a manufacturer of products … owes a duty to the consumer to take reasonable care’ The Sources of Law on Product Liability • Common Law: – contract – tort • Statute Law – Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cwth) – State fair trading legislation, State Sale of Goods legislation – Strict liability regime. Common Law: Negligence • Donoghue v Stevenson and the Common Law duty of manufacturers • The scope of the duty: – The extent of the duty: Junior Books v Veitchi (the duty extends beyond merely causing harm to safety or property) – Intermediate examination: Grant v. Aust. Knitting Mills – The range of defendants: Haseldine v. Daw The Act of the Defendant • Negligent design of product – O’Dwyer v. Leo Buring [1966] WAR 67 • Negligence in the manufacturing process: – Grant v. Australian Knitting Mills • Negligent Marketing of a Product – Adelaide Chemical & Fertilizer Co V. Carlyle • Failure to warn of dangers or proper use Norton Aust. Pty Ltd V. Steets Ice Cream Pty Ltd Statute • Sale of Goods Act (1923) NSW implies into contracts for sale of goods certain warranties: – fitness for purpose – merchantable quality – cannot be excluded Statute • Trade Practices Act (Comm) Pt V Div 2A – S74B Allows a consumer or person acquiring title through or under consumer an action against manufacturer in respect of goods unsuitable for purpose of sale. – S.74C : Action in respect of false description – S.74D: goods of unmerchantable quality – S.74E: goods not corresponding with sample – S.74K : No exclusion or modification of T.P.A The TPA: The manufacturer • Manufacturer: defined widely (S74A (3) & (4)) to include a corporation – -allows its name or brand on goods – -holds itself out as manufacture – -is importer & manufacture has no Aust place of business The TPA: The Consumer • CONSUMER: person acquiring goods where; – -prices does not exceed the prescribed amount ($40,000) – OR – -where price was greater but goods were of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal domestic or household use. The TPA: Remedies • S75AE: Remedy for other persons who suffer consequential losses. • S75AF: Remedy for damage to personal, domestic or household goods: • S75AG: Remedy for damage to land or buildings The TPA: Defences • Defences: S75AK • Contrib. Neg: S75AN • 3 year time limit: S75AQ The TPA Part VA • Pt VA T.P.A was enacted in 1992 and deals with the liability of manufacturers and importers of defective goods – S.75A: Applies to goods “if their safety is not such as person generally are entitled to expect” – S.75AD: A corporation supplying such goods is liable for damages to a person injured or killed Fair Trading Act (1987) (NSW) The Action: TPA or Tort • Under the TPA the Plaintiff does not prove: – -duty of care – -negligence • P should where possible plead 2 causes of action: – -in tort – -under TPA Abnormal Plaintiffs and Particularly Sensitive Plaintiffs • To be liable, P must show that she/he was foreseeable. In general the abnormal P is not foreseeable • There is a distinction to be drown between the abnormal Plaintiff and the particularly sensitive Plaintiff Abnormal Plaintiffs • In general where D is negligent, D takes P as he /she finds P. Any unusual condition that aggravates the damage cannot be used by D as a defence – Haley v. London Electricity Bd. A blind P held not to be abnormal: D “ought to anticipate the presence of such person within the scope and hazard of their operations” Particularly Sensitive Plaintiff • Where P suffers damage because of a particular sensitivity in circumstances where D’s conduct is not considered a breach, P cannot claim • Levi. V Colgate Palmolive – “the bath salts supplied to P were innocuous to normal persons… the skin irritation which she suffered…was attributable exclusively to hypersensitiveness” The Unborn Child • In general, a duty of care may be owed to P before birth – Watt v. Rama: “the possibility of injury on birth to the child was… reasonably foreseeable…On the birth the relationship crystallised and out of it arose a duty on the D…” – X v. Pal: Duty to a child not conceived at the time of the negligent act – Lynch v. Lynch:Mother liable in neg to her own foetus injured as result of mother’s neg driving. Wrongful Birth Claims • Claims by parents in respect of the birth of a child who would not have been born but for the D’s negligence. – Vievers v Connolly (1995) 2 Qd R 325 (Mother of disabled child born bec. Pl lost opportunity to lawfully terminate pregnancy. Damages included costs for past & future care of child for 30 years.) – CES v Superclinics (1995-6) 38 NSWLR 47 Mother lost opportunity to terminate pregnancy as a result of D’s neg failure to diagnose pregnancy. NSW Ct of Appeal held claim maintainable but damages not to include costs of raising the chills as adoption was an option. – Melchior v Cattanach [2001] QCA 246 Mother of healthy child after failed sterilization procedure. Qld CT Appeal held damages shld include reasonable costs of raising the child. Wrongful Life Claims • Claim by child born as a result of negligent treatment by De of child’s parent. • Bannerman v Mills (1991) ATR 81-079. Summary dismissal of claim by child born with disabilities as result of mother having rubella whilst pregnant. Tort of wrongful life unknown to common law Wrongful Life Claims • Edwards v Blomeley; Harriton v Stevens; Waller v James (2002 ) NSW Supreme Court, Studdert J. No duty of care to prevent birth Policy reasons - – 1. Sanctity & value of human life – 2. impact of such claim on self-esteem of disabled persons – 3. exposure to liability of mother who continued with pregnancy – 4.Plaintiffs’ damage not recognizable at law - would involve comparison of value of disabled life with value of nonexistence – 5.Impossibility of assessment of damages in money terms taking non-existence as a point of comparison. CLA Part 11 s71 • In any proceedings involving a claim for the birth of a child to which this Part applies, the court cannot award damages for economic loss for: (a) the costs associated with rearing or maintaining the child that the claimant has incurred or will incur in the future, or (b) any loss of earnings by the claimant while the claimant rears or maintains the child. (2) Subsection (1) (a) does not preclude the recovery of any additional costs associated with rearing or maintaining a child who suffers from a disability that arise by reason of the disability. Defective Premises • In general the occupier of premises owes a duty of care to persons who come on to the premises • While the notion of occupier's liability may have developed initially as a separate category of tort law, it now considered under the general principles of negligence – Zaluzna v Australian Safeway Stores Occupiers’ Liability • What are Premises? – -Land and fixtures – -but Cts have used wide interpretations including moveable structures eg: – scaffolding (London Graving Dock v. Horton [1951] AC 737 – Ships and gangways eg. Swinton v. China Mutual Steam Navigation Co Ltd (1951) 83 CLR 553 Occupiers’ Liability • Who is an occupier – control – Wheat v. Lacon [1966] AC 522 – Kevan v. Commissioner for Railways [1972] 2 NSWLR 710 The Liability of Public Authorities Introduction: Public Authorities and the Rule of Law • Applying the same rules of civil liability to the actions of public authorities or corporation: – The rationale: No legal or natural person is above the law – The difficulties: The nationalization and provision of public utilities and community facilities necessarily distinguish public corporations from ordinary citizens 49 The Rule of Law and Public Authorities • “When a statute sets up a public authority, the statute prescribes its functions so as to arm it with appropriate powers for the attainment of certain objects in the public interest. The authority is thereby given a capacity which it would otherwise lack, rather than a legal immunity in relation to what it does, … There is, accordingly, no reason why a public authority should not be subject to a common law duty of care in appropriate circumstances in relation to performing, or failing to perform, its functions, except in so far as its policy- making and, perhaps, its discretionary decisions are concerned” (per Mason J in Sutherland Shire 50 Council v Heyman) Some Basic Concepts: ‘Feasance’ • In tort law D is liable for a breach of duty towards P • The breach may take the form of an act (misfeasance) or an omission (non feasance) • However not every non-feasance provides a basis for liability: – Negligent omissions are actionable. – Mere/’neutral’ omissions are not actionable unless the D is under a pr-existing duty to act 51 Some Basic Concepts: Powers and Duties • Duty: – The obligation to act; the statutory provision/function is cast in mandatory terms – Once the content of the duty is determined, the question of breach is a question of fact – Breach duty attracts liability 52 Basic Concepts: Power • Power: – The statutory function is case in permissive terms – It confers on the power holder a choice to act in a particular way – The failure or refusal to exercise a choice may not necessarily be illegal. – The power holder has a freedom of choice to act/ The duty holder has an obligation to act 53 Some basic Concepts: Ultra Vires • It is for the power holder to decide what it wants to do within the limits of its powers • Where a power holder acts beyond the powers conferred on it by the relevant statute, the power holder’s conduct is ultra vires. The decision of the power holder has no legal effect and can be quashed by a court. 54 The Planning & Operational Dichotomy I • Planning decisions – Are based on the exercise of policy options or discretions – They may be dictated by social or economic considerations – not provide the basis for a duty • In general, a public authority is under no duty of care in relation to decisions which involve or are dictated by financial, economic, social or political factors or constraints 55 The Planning & Operational Dichotomy II • Operational decisions – The implementation of policy decisions – subject to the duty of care - L v Commonwealth (sexual abuse in prison, D held liable for operational failures) - Parramatta CC v Lutz (failure to order the demolition of building P’s property catches fire) Conclusions on the Basic Concepts: Ann’s Case • Intra Vires + Policy = Not actionable, Ct. will not interfere • Ultra Vires + Policy = Actionable, Ct will assess whether Neg or not • Not policy but Operational = Actionable, Ct will assess 57 Australian Approaches to the Liability of Public Authorities • Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman: Majority: Mason, Brennan & Deane JJ – in general no duty to exercise statutory powers – duty will arise where authority by its conduct places itself in a position where others rely on it to take care for their safety. – duty arises where D ought to foresee a) Pl. reasonably relies on D to perform function AND b) P will suffer damage if D fails. 58 Australian Approaches to the Liability of Public Authorities • Parramatta City Council v. Lutz: Maj of NSW Court of Appeal: Kirby P & McHugh JA – D held liable P because P had “generally relied” on council to exercise its statutory powers. – “I think… that this Court should adopt as a general rule of the common law the concept of general reliance 59 Australian Approaches to the Liability of Public Authorities • Pyrenees Shire Council v. Day Maj: Brennan, CJ, Gummow, Kirby, JJ – -rejected concept of General Reliance (too vague, uncertain, relies on “general expectations of community”) – (Only McHugh, Toohey, JJ approved and applied concept of General Reliance) – Brennan, CJ: No specific reliance by P here Duty arises where “Authority is empowered to control circumstances give rise to a risk and where a decision not to exercise power to avoid a risk would be irrational in that it would be against the purpose of the statute. 60 Australian Approaches to the Liability of Public Authorities • Crimmins v. Stevedoring Industry Finance Committee (1999) 167 ALR 1: McHugh J, Gleeson CJ agreeing – was it RF that Ds act or omission incl failure to exercise stat power would cause injury? – Did D have power to protect a specific class incl Pl (rather than Public at large) – Was Pl vulnerable – Did D know of risk to specific class incl P if D did not exercise power – Would duty impose liability for “core policy making” or “quasi-legislative” functions. – Are there Policy reasons to deny duty 61 Australian Approaches to the Liability of Public Authorities • Ryan v. Great Lakes Council Federal Court of • Australia 9 August, 2000 -In a novel case involving a statutory authority the issue of duty should be determined by the following questions: – 1.was it RF that act or omission would cause injury – 2.Did D have power to protect a specific class including Pl (rather than public at large) – 3. Was P vulnerable – 4.Did D know (or ought D have known) of risk – 5.Would duty impose liability for “core policy making” or “quasi legislative” functions> if so then NO duty 62 – 6.Are there Policy reasons to deny duty? Mis-feasance and NoneFeasance: Highway Authorities • The traditional position in Common Law: – Highway authorities owe no duty to road users to repair or keep in repair highways under their control and management. – Highway authorities owe no duty to road users to take positive steps to ensure that highways are safe for normal use. • It is well settled that no civil liability is incurred by a road authority by reason of any neglect on its part to construct, repair or maintain a road or other highway. Such a liability may, of course, be imposed by statute. But to do so a legislative intention must appear to impose an absolute, as distinguished from a discretionary, duty of repair and to confer a correlative private right. (per Dixon J in Buckle v Bayswater Road Board): See also Gorringe v. Transport 63 Comm. Misfeasance and non-Feasance: Common Law Developments • Brodie v. Singleton Shire Council • Ghantous v. Hawkesbury City Council 64 The Civil Liability Act (NSW) and Public Authorities Part 5 of the Civil Liability Act (Sections 40 to 46) • Section 42 sets out the principles to determine duty of care exists or has been breached (ie. financial and other resources reasonably available, allocation of resources, broad range of its activities, and compliance with the general procedures and applicable standards) • Section 43: act or omission not a breach of duty, unless it so was unreasonable that no authority having the functions in question could properly 65 consider it as reasonable. The Civil Liability Act (NSW) and Public Authorities • Section 44: Removes the liability of public authorities for failure to exercise a regulatory function if the authority could not have been compelled to exercise the function under proceedings instituted by the Plaintiff. • Section 45: Restores the non-feasance protection for highway authorities taken away by the High Court in Brodie v Singleton Shire Council Council; Ghantous v Hawkesbury City Council 66 LIABILITY FOR DEFECTIVE STRUCTURES • Builders, developers, engineers, architects, (as non-occupiers) all owe a DUTY of CARE to visitors or occupiers of negligently constructed buildings ( basic principles of negligence apply) – Bryan v. Maloney 67 Defective Structures and the Liability of Public Authorities • Pyrenees Shire Council v Day 68