Syllabus - Brandeis University

advertisement

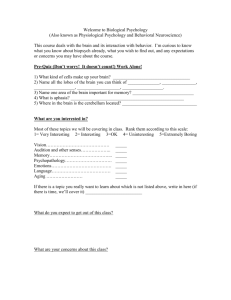

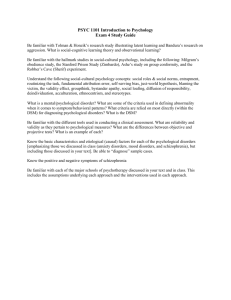

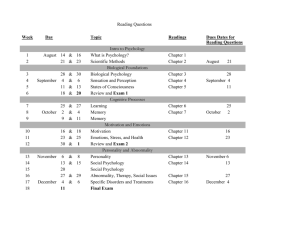

1 Abnormal Psychology Psych 32 – Spring 2014 Instructor: Ellen J Wright, PhD Office Phone #: 781-736-2809 Office: Brown 128 Office Hours: Tu 1-2:30, W 9-10:30, or by appointment Email ejwright@brandeis.edu (best way to contact) Olin-Sang Amer Civ Ctr101, TuF 9:30-10:50, Graduate Teaching Fellow: Carrie Robertson Office and Office Hours: Brown 15, office hours – Wednesday 5-6:30, or by appointment Email: carrob@brandeis.edu Graduate Teaching Fellow: Nicholas Brisbon Office and Office Hours: Brown 104; office hours – Email: nbris@brandeis.edu Undergraduate Peer Assistant: Kyra Borenstein Office and Office Hours: Library, Green Room; office hours – Th 11-12 Email: kyrajb@brandeis.edu Required Texts: Barlow and Durand Clipson & Steer Abnormal Psychology: An integrated approach Cengage Case Studies in Abnormal Psychology Houghton Mifflin 7e (or the 6th ed) 1998 Explanation of Reading Assignments: Required. Recommended. Minimal reading for the course. These are on the course Latté. A more thorough exposition of the material that is covered briefly in the required readings or in class. This is helpful to those who want a fuller understanding of the material in the course and provides a source of ideas for the optional paper. Course Objectives To gain an understanding of those behaviors and syndromes that have traditionally fallen under the heading of “abnormal” or “psychopathological;” To gain an understanding of the very exciting research on the etiology, dynamics, description, and course of “maladaptive” behavior; To gain an understanding of how nature and nurture interact in the process of developing “maladaptive” behavior, and to understand the factors that affect developmental trajectories (including risk and protective factors); To learn how to evaluate the clinical evidence regarding psychopathology Obviously, these are big goals. I hope to get the ball rolling to help you become life-long learners who are excited by the world you see; yet skeptical about explanations you receive. Attendance: Attendance of this class is NOT mandatory. The professor (sometimes erroneously) assumes that presence in a college class is synonymous with adulthood. However, lecture material will NOT duplicate the text, as the professor (also often erroneously) assumes the students can and will read the assigned information and would like more from the course than that. Further, test questions will be sampled equally from lecture and assigned text readings. We will NOT repeat lectures on an individual basis. Special Needs If you are a student with a documented disability on record at Brandeis University and wish to have a reasonable accommodation made for you in this class, please see me immediately. 2 Academic Honesty: You are expected to be honest in all of your academic work. The University policy on academic honesty is distributed annually as section 5 of the Rights and Responsibilities handbook. Instances of alleged dishonesty will be forwarded to the Office of Campus Life for possible referral to the Student Judicial System. Potential sanctions include failure in the course and suspension from the University. If you have any questions about my expectations, please ask. Course Requirements 1. Exams: you will have two in-class examinations, with the second exam occurring during finals week. Both tests will be worth 100 points each, and will include a combination of multiple choice, matching, and shortanswer questions. This exam will cover all the required material in sections I, II and III and all lectures related to these sections. The second test will include a case history component and will be worth 150 points. The objective portion (multiple choice, matching, short answer) of the final will only cover sections IV, V, and VI and all lectures related to these sections. Lecture, all in-class materials and discussions, and reading assignments will be covered in both exams. In addition to the second exam, a take-home, case history portion will be assigned to be accomplished independently and brought to the final exam, printed out and stapled with your names affixed. This case study will be worth 50 points. The ONLY excuses acceptable for missing an exam is illness (documented by a note from a physician), funeral of close friend/relative (documented by a funeral notice or funeral bulletin), mandatory religious obligations or other unavoidable circumstances or University activities. If you must be away at the time of an examination, you may schedule an early exam. You will receive a review sheet (posted on Latté) that will serve as a general guide. Test questions will not be limited to this review sheet, but the short questions posed on the review sheet and the case history practice should help prepare you for the short-answer questions and the case history segment. 2. Forum questions: each section will include a series of forum questions designed to provoke critical thinking about the research reading. Thought questions will be posted and students are expected to post at least once on each section throughout the course of the semester. 3. Creative assignment: Literature plays a critical role in each culture’s view of humanity. For this assignment, you are expected to choose one of the books listed below and complete the assigned essay (essay questions will be posted on Latté). Topic due 1/31, Creative Project Due – 3/21 Choice of... Jamison, K. R. (1997). An unquiet mind: A memoir of moods and madness. Random House. Lamb, W. (1992). She's come undone. NY: Washington Square Press. Hornbacher, M. (1998). Wasted. Harper. Lamb, W. (2008). I know this much is true. Harper Perennial. Harris, T. (1993). Silence of the lambs. Mass Market Paperback. 4. Optional Paper: 1. You may write a paper that is a critical review of an area of research in experimental psychopathology. This paper is optional and will be counted as extra credit in the following way: If the paper grade is equal to or a half grade above (meaning one or two grade steps, including +’s and –‘s) above your overall exam average, your course grade will be increased one grade step. Thus, a B, B+ or A- paper will change a B exam average to a B+ course average. If the paper grade is a full grade above your exam average (that is, three or more grade steps), your grade will be increased two steps. Thus an A paper will change a B Grade to an A-. No more than two grade steps in extra credit can be earned by a paper. 2. The paper should be an in-depth review of a limited topic rather than a surface survey of a broad topic. Secondary sources will be helpful for finding topics and giving you an overview. The paper itself, however, should be based primarily on primary sources (i.e., on journal articles reporting the results of 3 experimental investigation). It should make an effort to include the most relevant literature on the topic. Omission of frequently cited, critical papers on a topic will be negatively evaluated. Papers that are only a rehashing of secondary sources will not earn above a “D.” 3. Look for the most recent research you can find. You should become familiar with and use the Psychological Abstracts in the reference section of the library or the PSYCINFO electronic database. You can use references from any time period, but woe be it to anyone whose most recent reference is before 2000. 4. Papers will be graded according to the following criteria: GRADE A Paper reflects an understanding of the material. It presents an organized, critical analysis and creative integration of the relevant data, relating it to our knowledge of psychological processes in and/or to our knowledge of personality and psychopathology. B Paper reviews the material well and makes some attempt to analyze, criticize, and interpret the data in terms of our knowledge of psychological processes. C Paper reviews the material adequately, but does not integrate the data well or analyze it. D Paper reviews the material inadequately or only rehashes material in secondary sources (like text books or review articles), but the individual has demonstrated some learning. E The individual demonstrates that she/he has learned nothing in the course. 5. Mechanics (a) Length: Paper should be between 10 and 20 pages of text, double-spaced, and the smallest print you should use is 12 point Times. This corresponds to the smallest print size allowed by the government for grant submissions. Absolutely nothing will be read past these limits. (b) Margins on the pages should be 1 inch on all sides, top/bottom, left/right. (c) All papers must be typed double space on bond paper. (d) Follow the guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) for the form and style of the paper, most importantly following the recommended method of citing references. (Guidelines for APA style will be posted in the first Latté block, and example papers and further APA guidelines will be posted in the bottom Latté block). (e) Please do not put papers in folders. Staples or paper clips do an adequate job. (f) Put a title at top of first paper--do not put your name on the first page. This will make it easier for us to make an objective, unbiased assessment of your paper. (g) Make a complete title page with your name and put it at the end of the paper (after the references). (h) Please make a copy (photocopy or second printing) of your reference section and attach it to the paper. This copy I will keep for my files to help other students who will be writing papers in the future. It is also smart to keep a copy of the paper for yourself. 6. Your topic should be approved by a teaching assistant or by the professor by February 14th. This is to assure that you do not pursue a topic that is suboptimal or not within the purview of the course. The assistants should be able to help you limit the topic and might have some suggestions about important references. 7. The optional paper is due no later than Tuesday, April 29th. Because this paper is an optional, extra credit paper, no papers will be accepted after this date. If I do not have a paper by this date, I will automatically assume that you have chosen the no-paper option. If you are interested in writing a paper, you should begin work now or shortly. 4 Please Note: The content on this syllabus is tentative. The instructor maintains the right to make changes to the readings and the timing of the content as the course progresses. This need will be dictated by the interest of the class and the uncontrollable loquacity of the instructor. We will cover as much material as we can, but I will go neither so quickly that students are lost, nor so slowly that the lecture becomes unbearably repetitive. However, assignment and exam dates are inflexible. TOPICS Dates Topics Readings 1/14 1/17 Introduction History and Paradigms Text 1 Text 2 1/21 Paradigms (contd.) 1/24 Diagnosis & Assessment, Research Methods Rosenhan, Szasz, Spitzer, Kendler Text 3,4, Case #1, Ausubel, Snyder et al. 1/28 1/31 Case Dynamics and Coping Anxiety Disorders Lazarus Text 5, Moffitt et al., Nestadt et al., Case 2 2/4 2/7 Anxiety (contd.) Dissociative and Somatoform Disorders Cases 3, 4 Text 6, Lilienfeld & Lynn 2/11 2/14 Dissociative and Somatoform (contd.) Psychophysiological Disorders 2/17-2/21 February Vacation 2/25 2/28 Substance Issues Substance (contd.) 3/4 3/7 Midterm Exam Personality Disorders 3/11 3/14 PDs (contd.) PDs (contd.) Cases 12-13 Blackburn; Waldman & Rhee 3/18 3/21 Mood Disorders MDs (contd.) Text 7, Cases 5-6 Alloy et al. 3/25 MDs (contd.) 3/28 Eating Disorders Flynn et al., Gotlib & Robinson Text 8, Case 15 Text 9, Case 8, Adler & Matthews Assignments/Due Dates Creative Paper Topic due Optional Paper Topic due Text 11, Case 9 Text 12 Creative Paper due 5 Dates Topics Readings 4/1 EDs (contd.) 4/4 Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders Fairburn, Fladung et al. Text 13 4/8 4/11 4/15-4/22 Sz & PsyD (contd.) Sz & PsyD (contd.) Passover Holiday 4/25 Sz & PsyD (contd.) 4/29 Sz & PsyD (contd.) Assignments/Due Dates Optional Research Paper due Final Exam + Case Study – Exam period I. Introduction Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapters 1 through 4. Clipson & Steer (1998): Case #1. Ausubel, D. (1961). Personality disorder is disease. American Psychologist, 16, 69-74. Kendler, K.S. (2005). Toward a philosophical structure for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 433-440. Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179, 250-258. Spitzer, R. L. (1976). More on pseudoscience in science and the case for psychiatric diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33, 459-470. Snyder, C. R., Shenkel, R. J., & Lowery, C. R. (1977). Acceptance of personality interpretations: The "Barnum Effect" and beyond. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45, 104-114. Szasz, T. S. (1960). The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist, 15, 113-118. Recommended Readings: Bromberg, W. (1959). The mind of man: A history of psychotherapy and psycho-analysis. New York: Harper & Row. Eysenck, H. J. (1986). A critique of contemporary classification and diagnosis. In T. Millon & G. Klerman (Eds.), Contemporary directions in psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press. Grove, W. M., & Meehl, P. E. (1996). Comparative efficiency of informal (subjective, impressionistic) and formal (mechanical, algorithmic) prediction procedures: The clinical-statistical controversy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 2, 293-323. Grove, W. M., Zald, D. H., Lebow, B. S., Snitz, B. E., & Nelson, C. (2000). Clinical versus mechanical prediction: A meta-analysis. Psychological Assessment, 12, 19-30. Lilienfeld, S. O., & Marino, L. (1995). Mental disorder as a Roschian concept: A critique of Wakefield’s ‘harmful dysfunction’ analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 411-420. Nathan, P. E., & Langenbucher, J. W. (1999). Psychopathology: Description and classification. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 79-107. Raulin, M. L., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (1999). Research methods for studying psychopathology. In T. Millon, P. H. Blaney, and R. D. Davis (Eds.), Oxford textbook of psychopathology (pp 49-78). New York: Oxford University Press. Wakefield, J. C. (1992). The concept of mental disorder: On the boundary between biological facts and social values. American Psychologist, 47, 373-388. II. Stress, Coping, Anxiety Disorders Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapters 5 Clipson & Steer (1998): Cases #2, 3, 4 6 Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55, 665-673. Lilienfeld, S. O., & Lynn, S. J. (2003). Dissociative Identity Disorder: Multiple personalities, multiple controversies. In S. O. Lilienfeld, S. J. Lynn, & J. M. Lohr (Eds.), Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (pp. 109-142). New York: Guilford Press. Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Caspi, A., Kim-Cohen, J., Goldberg, D., Gregory, A. M., & Poulton, R. (2007). Depression and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 651-660. Nestadt, G., Samuels, J., Riddle, M., Bienvenu, O. J., Liang, K. Y., LaBuda, M., Walkup, J., Grados, M., & Hoehn-Saric, R. (2000). A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 358-363. Recommended Readings: Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 577-584. Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Further processes for adaptation. American Psychologist, 55, 637-646. Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (2001). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders (pp. 1-59). New York: The Guilford Press. Hirsch, C.R., & Clark, D.M. (2004). Information-processing bias in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 799-825. Rachman, S. (1997). A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 793-802. Rapoport, J. L., & Fiske, A. (1998). The new biology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Implications for evolutionary psychology. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 41, 159-175. Roth, W.T., Wilhelm, F.H., & Pettit, D. (2005). Are current theories of panic falsifiable? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 171-192. Somerfield, M. R., & McCrae, R. R. (2000). Stress and coping research: Methodological challenges, theoretical advances, and clinical applications. American Psychologist, 55, 620-625. Spanos, N.P. (1994). Multiple identity enactments and multiple personality disorder: A sociocognitive perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 143-165. Yehuda, R. (2002). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 346, 108-114. III. Psychophysiological Disorders Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapter 9 Clipson & Steer (1998): Case: 8 Adler, N., & Matthews, K. (1994). Health psychology: Why do some people get sick and others stay well? In L. Porter & M.R. Rosenweig, (Eds.) Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 229-259. Recommended Readings: Everly, G. S. (1986). A biopsychosocial analysis of psychosomatic disease. In T. Millon & G. Klerman (Eds.), Contemporary directions in psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press. IV. Substance Issues and Personality Disorders Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapters 11, 12 Clipson & Steer (1998): Cases #12 & 13. Blackburn, R. (2006). Other theoretical models of psychopathy. In C. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy, pp. 35-57. New York: Wiley. Waldman, I. D., & Rhee, S. H. (2006). Genetic and environmental influences on psychopathy and antisocial behavior. In C. l (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy, pp. 205-228. New York: Wiley. 7 Recommended Readings: Battle, C. L., Shea, M. T., Johnson, D. M., Yen, S., Zlotnick, C., Zanarini, M.C. et al. (2004). Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: Findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18, 193-211. Hare, R. D. (1998). Psychopaths and their nature: Implications for the mental health and criminal justice system. In T. Millon, E. Simonson, M. Birket-Smith, & R.D. Davis, (Eds.), Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior (pp. 188–212). New York: Guilford Press. Iacono, W. G., Malone, S. M., & McGue, M. (2003). Substance use disorders, externalizing psychopathology, and P300 event-related potential amplitude. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 48, 147-178. Krueger, R. F., Markon, K. E., Patrick, C. J., & Iacono, W. G. (2005). Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 537-550. Lenzenweger, M. F., & Clarkin, J. E. (1996). The personality disorders: History, classification, and research issues. In J. E Clarkin & M. F Lenzenweger, (Eds.), Major theories of personality disorder (pp. 1-35). New York: The Guilford Press. Pettit, G. S., & Dodge, K. A. (Eds.). (2003). Violent children [Special Issue]. Developmental Psychology, 39(2). Widiger, T. A. & Simonsen, E. (2005). Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: Finding a common ground. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 110-130. V. Mood and Eating Disorders Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapters 7, 8. Clipson & Steer (1998): Cases #5, 6, 15. Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Walshaw, P. D., Gerstein, R. K., Keyser, J. D., Whitehouse, W. G., Urosevic, S., Nusslock, R., Hogan, M. E., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Behavioral approach system (BAS)–relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 459-471. Flynn, M., Kecmanovic, J., & Alloy, L.B. (2010). An examination of integrated cognitive-interpersonal vulnerability to depression: The role of rumination, perceived social support, and interpersonal stress generation. Cognitive Therapy Research, 34, 456–466. Gotlib, I.H., & Robinson, L.A. (1982). Responses to depressed individuals: Discrepancies between self-report and observer-rated behavior, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 91, 231-240. Fairburn, C.G. et al. (2003). Understanding persistence in Bulimia Nervosa: A 5-year naturalistic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 103-109 Fladung et al. (2010). A neural signature of Anorexia Nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 206–212. Recommended Readings: Cuellar, A.K., Johnson, S.L., & Winters, R. (2005). Distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 307-339. Davidson, R. J., Pizzagalli, D., Nitschke, J. B., & Putnam, K. (2002). Depression: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 545-574. Fairburn, C.G. et al. (2007). The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: Implications for DSM-V. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1705-1715. Gotlib, I. H., Krasnoperova, E., Yue, D. N., & Joormann, J. (2004). Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 127-135. Hatch et al. (2010). Emotion brain alterations in Anorexia Nervosa: A candidate biological marker and implications for treatment. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 35, 267-274. Kessler, R. et al. (2003). The epidemiology of major depression disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3095-3105. Lewinsohn, P. M., Allen, M. B., Seeley, J. R., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). First onset versus recurrence of depression: Differential processes of psychosocial risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 483-489. Monroe, S. M., Slavich, G. M., Torres, L. D., & Gotlib, I. H. (2007). Major life events and major chronic difficulties are differentially associated with history of major depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal 8 Psychology, 116, 116-124. Nesse, R. M. (2000). Is depression an adaptation? Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 14-20. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 259-282. Paul, T., Schroeter, K., Dahme, B., & Nutzinger, D.O. (2002). Self-injurious behavior in women with eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 408-411. VI. Schizophrenia Required Readings: Barlow & Durand (2014). Chapter 13. Clipson & Steer (1998): Case #7. Erlenmeyer-Kimling, L., Roberts, S. A., Rock, D. (2004) Longitudinal prediction of schizophrenia in a prospective high-risk study. In L. F. DiLalla (Ed.), Behavior genetics principles: Perspectives in development, personality, and psychopathology (pp. 135-144). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Knight, R.A. & Valner, J.B. (1993). Affective deficits in schizophrenia. In C. G. Costello (Ed.), Symptoms of Schizophrenia. New York: John Wiley. Sullivan, P. F., Kendler, K. S., & Neale, M. C. (2003). Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 1187-1192. Walker, E., Kestler, L., Bollini, A., & Hochman, K. M. (2004). Schizophrenia: Etiology and course. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 401-430. Recommended Readings: Andreasen, N. C., Paradiso, S., & O’Leary, D. S. (1998). “Cognitive Dysmetria” an integrative theory of schizophrenia: A dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebella circuitry. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24, 203218. Fowles, D.C. (19920. Schizophrenia: Diathesis-stress revisited. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 303-336. Gottesman, I. I., & Moldin, S. O. (1998). Genotypes, genes, genesis, and pathogenesis in schizophrenia. In M. F. Lenzenweger & R. H. Dworkin (Eds.), Origins and development of schizophrenia: Advances in experimental psychopathology (pp. 247-295). Washington DC: APA Press. Heston, L.L. (1966). Psychiatric disorders in foster home reared children of schizophrenic mothers. British Journal of Psychiatry, 112, 819-826. Hooley, J. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2000). A diathesis-stress conceptualization of expressed emotion and clinical outcome. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 9, 135-151. Kempf, L., Hussain, N., & Potash, J.B. (2005). Mood disorder with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia with mood features: Trouble at the borders. International Review of Psychiatry, 17(1), 9-19. Meehl, P.E. (1990). Toward an integrated theory of schizotaxia, schizotypy, and schizophrenia. Journal of Personality Disorders, 4, 1-99. Optional paper due no later than Tuesday, April 29th VII. Treatment - Psychotherapy, Behavior Modification, etc. We will not have time to discuss treatment in class. If you are interested in treatment, you should take Psych. 167b, Schools of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. Chapter 16 is a brief introduction to various methods and can be read at your leisure. This chapter is not, however, required.