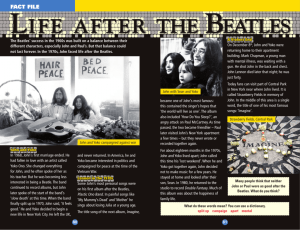

The Art and Life of Yoko Ono

advertisement