VVFP 2011: Msgr Gordon presentation, 'A Christian moral framework'

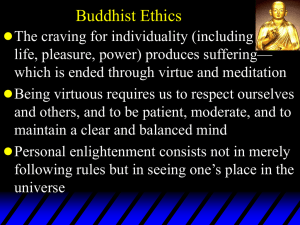

advertisement

TOWARDS A MORAL FRAMEWORK Learning to be Moral How we will learn In our sessions we will: Explore the moral framework Reflect on our moral framework Reflect upon how to teach morality to our children. Reflect upon the relevance of the conversation to the program. Reflect upon how to teach the parents. Ethics and Morality "[Ethics is] is the philosophical study of morality. The word is also commonly used interchangeably with 'morality' to mean the subject matter of this study; and sometimes it is used more narrowly to mean the moral principles of a particular tradition, group, or individual. Christian ethics and Albert Schweitzer's ethics are examples." -- John Deigh in Robert Audi (ed), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 1995 Does good and bad exist? How do we know that something is good or bad? Good Vs Evil Things Considered “Good” Things Considered “Bad” Justice Injustice Kindness Cruelty Wisdom Folly Freedom Slavery Respect Selfishness Peace Murder Courage Cowardice Love Hatred Hope Despair Why do we consider some things good and others bad? Where Do Our Moral Values Come From? Where Do Our Moral Values Come From? This question is the most basic and important in the study of ethics and it has two possible answers: that values are OBJECTIVE or SUBJECTIVE. Do we discover these values as a scientist would, in objective reality or do we create these values like the rules of a game or a work of art? Looking at history, we can see that pre-modern societies saw these values as objective, and as universal, absolute and unchanging Ethics is about three things: 1. Good—the thing desired, the ideal 2. Right—the opposite of wrong as defined by some law 3. Ought—personal obligation, duty, responsibility using a metaphor supplied by C.S. Lewis in which we are a fleet of ships and ethics are our sailing orders. These orders tell the ships (us) three things: 1. How to cooperate with one another and thus avoid bumping into to each other. This is Social Ethics. 2. How to keep each ship afloat and in good condition. This is Individual Ethics or Virtue Ethics. It asks the questions: What is a good person? What is moral character? 3. What the ship’s mission is. This is the most important “order” of all, for it gives us our ultimate purpose and goal in life. If we don’t know or care where we are going, it doesn’t make a difference what road we choose. (QUO VADIS?) Can Virtue be Taught? Meno asks Socrates, “Can virtue be taught, or does it come to us in some other way? Do we get virtue by: 1. Teaching 2. Habit and practice 3. Innately, by nature 4. By going against nature How do we Become Virtuous? Most optimistic-----nature---- Rousseau Less optimistic -----By teaching---- Plato Even less optimistic ----By work/practice---- Aristotle’s Pessimistic --By force/against nature --Machievelli/ Hobbes Virtue For Aristotle "Virtue, then, is a habit or trained faculty of choice, the characteristic of which lies in moderation or observance of the mean relatively to the persons concerned, as determined by reason, i.e. as the prudent man would determine it." Virtue For Aristotle Virtue is the state of experiencing the passions and acting: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. at the right time with reference to the right objects towards the right people with the right motive in the right way "virtue" (arete) = excellence in fulfilment of a particular function Virtue For Aristotle Strength of character (habit) Involving both feeling and action Seeks the mean between excess and deficiency relative to us Promotes human flourishing Virtue and the Mean General/universal rule: "Virtue then is a state of deliberate moral purpose consisting in a mean that is relative to ourselves, the mean being determined by reason...." The mean is not mathematical it is not the half way point, but rather the appropriate for the person. The Virtuous Mean Passion Deficiency MEAN Excess Fear/Confidence Cowardice COURAGE Rashness Pleasure/Pain Insensible TEMPERANCE Self-indulgence Anger Unirascible GOOD TEMPERED Irascible Wealth Meanness LIBERALITY Prodigality Do we still see morality this way? Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 1. For the ancients, Ethics comes first. They saw ethics as the single most important ingredient in a good life. For the ancients morality is not a means to an end, it IS the end. 2. Within “ancient wisdom” is a profound respect for tradition and authority. The ancients believed in an obedience or conformity to authority not in the sense of “power” but of “goodness.” They believed that right makes might, not that might makes right. Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 3. The ancients did ethics by reason and with the mind not with feelings or emotion as is often done in the modern world. The ancients believed the maxim—“LIVE ACCORDING TO REASON.” 4. Ancient ethics was more connected to religion, while modern ethics is more deliberately secular. Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 5. Because of their deeper concept of happiness as objective perfection and not just subjective contentment, and their deeper concept of ethics as not just rules but virtues, the ancients did not contrast ethics and happiness as we often do today. 6. All ancients based their ethics on human nature. This is one of the meanings of the term “natural law.” Modern philosophers tend to base their ethics either on desire and satisfaction Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 7. For the ancients the most important question in ethics was not how to treat other people, or how to have a just society, or how to improve the world, or even how to be a good person, or what virtues to have (all these questions were of course important) but the most important question was the question of the meaning of life. What was life’s ultimate purpose or final goal or greatest good summum bonum? 8. Most of the ancients believed that politics was social ethics. This meant that there was no radical difference between societal and individual ethics. Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 9. Most of the ancients believed that human nature had both good and evil tendencies in it. Many moderns believe this too, but three other views. i. The idea of Pessimism, that man is innately bad and it takes force to make him act well. ii. The idea that we have no essence. Human nature is just a word that is ever-changing and malleable. iii. The idea of optimism, which holds that man is innately good, 10. Moderns tend to rely on science as being more reliable than religion. Twelve Important Differences Between Typically Ancient and Typically Modern Ethical Philosophies 11. In ancient philosophies, ethics was based on metaphysics. Ethics, or your “life view,” depended on your “world view,” or metaphysics. 12. Most of the ancients would say that what makes a society survive and prosper is ethics. A modern would say it is economics. Your ethical principals are they more ancient or more modern? Your ethical principals are they more Christian or more secular? FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY Does God know what I am going to do next? Freedom Without Freedom can we speak about morality? Can a computer be moral? Within morality there are two notions of freedom. Freedom of self determination Freedom of choice Are we fundamentally free? Self-Determinism and Freedom Genetic—My genetic structure somehow determines my moral actions. Environmental—My upbringing determines my moral actions. Psychological—my psychological structure determines my moral actions. The case of the twins All three have truth but the extreme formulation is untrue. Self-Determinism and Freedom The behavioral sciences show us that freedom is limited. Yet human experience and the ability to transcend ourselves culturally and morally suggests that determinism is not absolute. We do not start from a position of equality In the moral life we do the best we can do with what we have been given. Self-Determinism and Freedom Can we be held morally responsible for what is a given in our life? E.g. our genetic makeup What is the moral response to the hand of cards that life has dealt us? Core Freedom The ability to decide to make someone of oneself. What we do eventually becomes who we are. This is a moral choice that is posed to us every day in the little decisions. The choice for who we will become. The human is a complex multi-layered being Basic Freedom Basic Freedom Fundamental option The significant moments of choice in our lives that establish or affirm more strongly than others the character and direction of our lives. What led us to our life options? Fundamental option God has created us out of love and for love. IF we allow God’s love to penetrate us (we choose) an orientation towards love and life. Luke 18:1-8 Fundamental Stance We cannot lay claim to having a fundamental direction in our life until we have come to a stable identity. Identity and Stance arise through commitment to a way of life that is stable enough to sustain an indestructible quality of life and thus give personal meaning to actions. Actions find their meaning within the fundamental direction of ones life Commitment is necessary for the good life. Fundamental option Choice rooted in deep knowledge of self. Rooted in a freedom to commit oneself This is the freedom of self-determinism to commit to a certain way of being in the world. Fundamental Choice Realizing our capacity to be ourselves through the specific choices we make. Choosing one option from a number of good options—Smorgasbord Choice here is subject to hereditary determinants, our basic inclinations, unconscious motives, peer pressure, ignorance, passions, fears, blind habits and cultural norms. Fundamental choice The choice in the face of all of the limitations and blind spots, to be the person we most deeply want to become. This is a choice to know the person choosing. To choose not to know, or not to orient your life towards the good, or to choose to be, less than one is capable of, is sin. Sin In the pre-Vatican II church sin was used to prevent moral choice Sin and fear were used to force the faithful to keep rules without reflection on who they were becoming. How do we speak about sin in a world come of age? Sin: Biblical perspectives Hattab—to miss the mark or to offend. Pesa—Rebellion. This speaks of relationship that already exists. The offence is against the relationship. This is a legal term denoting deliberate action violating a relationship in community. Bamartia—Deliberate action rooted in the heart and missing the mark. Sin and Covenant Only makes sense if we believe in a God who first loved us—covenantal love. Unlike the Godfather God makes us an offer that we can refuse. Hessed—Hosea’s covenantal love. Biblical sin is not the nasty little things that are shameful. It is breaking covenantal love. Covenant Being a child of God Solidarity Fidelity—to God, Others, Creation and Self Original Sin It is different from personal sin It originates before we were born It is bigger than our individual choices. We ultimately cannot take responsibility for all the evil in the world. Original Sin Original sin is the theological code word for the human condition of living in a world where we are influenced by more evii than what we do ourselves. Our whole being and environment is infected by this condition of evil and brokenness willv—nilly. Sin: Gradation Sin that excludes from the Reign of God (1 Cor6:910; Gal 5:19-21) Sin that cannot be forgiven (Mk 3-28-30)— Blasphemy against the Holy Spirit. Those that are deadly (1John 5:16-17) Mortal Sins Tertullian--idolatry, blasphemy, murder, adultery, fornication, false witnessing, fraud, and lying. Fourth Lateral council (1215) Obligation for annual confession for those who committed mortal sin. Mortal sin Criterion: Sufficient Reflection Full consent of the will and serious matter This implies freedom. Negative fundamental option Moral life as a story Individual actions –the events that make up the story We cannot interpret the events outside of the whole narrative (moral life) The plot is the fundamental orientation that we only discover after we are already well into the story. The plot is discovered by reading back Self knowledge To name something mortal sin we must consider the degree of self possession and self determination that goes into the act. To do this for our self is difficult enough, what about trying to achieve this for another? Sin Venial sin—the acts that lead to a negative fundamental option. Social sin—structures that blind society to its fundamental option What do we Catholics do when we know that we have sinned? Responsibility The ability to respond (Stephen Covey) We are not victims. We always have a choice to make. Responsibility God is acting in all events that make up our lives thus to respond is to respond to God. Not to respond to God is sin. From the biblical perspective this is what is involved in the covenant. Vocation 5 “Before I formed you in the womb I knew[a] you, before you were born I set you apart; I appointed you as a prophet to the nations.” (Jer 1) 1 Listen to me, you islands; hear this, you distant nations: Before I was born the LORD called me; from my mother’s womb he has spoken my name. (Is 49) Vocation: Four levels of God's call Our life vocation-priest, teacher, mother, father, doctor, etc (external) The way God called us from the wombp (personal/ internal)p The call of God to us in each momentzqaAawaqaqa The call of God to his church p Caritas in Veritate 16. Paul VI taught that progress, in its origin and essence, is first and foremost a vocation: “in the design of God, every person is called upon to develop and fulfill himself, for every life is a vocation .” This is what gives legitimacy to the Church's involvement in the whole question of development. 39 Caritas in Veritate Integral Human Development: The first is that the whole Church, in all her being and acting — when she proclaims, when she celebrates, when she performs works of charity — is engaged in promoting integral human development. The second truth is that authentic human development concerns the whole of the person in every single dimension Moreover, such development requires a transcendent vision of the person, it needs God: without him, development is either denied, or entrusted exclusively to man, who falls into the trap of thinking he can bring about his own salvation, and ends up promoting a dehumanized form of development (#11). 46 Four disconnects (2bcatholic) 1. 2. 3. 4. Between the idea of social justice and the commitment that is required to build a better world Between the idea of community and the personal responsibility and commitment to build a community which serves all people. Between the understanding of doctrine in the Church, and the importance of Scripture Between prayer as the relationship one has with God and action. (Regional seminary students) 5 Pope Paul VI-Less Human Conditions The lack of material necessities for those who are without the minimum essential for life, The moral deficiencies of those who are mutilated by selfishness. Oppressive social structures, whether due to the abuses of ownership or to the abuses of power, to the exploitation of workers or to unjust transactions. 47 Pope Paul VI-More human the passage from misery towards the possession of necessities, victory over social scourges, the growth of knowledge, the acquisition of culture. increased esteem for the dignity of others, the turning toward the spirit of poverty,[18] cooperation for the common good, the will and desire for peace. 48 Pope Paul VI-More Human The acknowledgment by man of supreme values, and of God their source and their finality. Faith, a gift of God accepted by the good will of man, and unity in the charity of Christ, Who calls us all to share as sons in the life of the living God, the Father of all men. 49 THE MORAL ACT Living As Becoming The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. Human Action 1. 2. 3. Traditional morality has used a three-prong principle to determine the morality of human action: The intention The act-in-itself The circumstances The Intention The intention is the internal part, or the formal element of the moral action. It is also called the “end,” or that which we are after in I doing what we do I.e., the whole purpose of our action. The intention gives personal meaning to the action. The Act-in-itself The act-in-itself, or the means-to-an-end, This is the external part, or the material element of the moral action. It is so easily observed that it could be photographed. According to the theory of St. Thomas, the act-initself cannot be accurately evaluated as moral or immoral apart from considering the intention of the person acting The Act-In-Itself St. Thomas: The material event of an act cannot be evaluated morally without consideration of the subject, the inner act of the will or of the end. The Act-in-itself becomes a human act when it is directed towards an end within the inner act of the will. A photograph cannot tell the morality of an act. Different intensions constitute different human actions. Circumstances To determine the morality of an act the circumstances must be considered. Killing can be murder or self defense. The circumstances are necessary to determine whether a physical act is proportionate to the intention. Using a gun to defend your self against an unarmed child, is not proportionate. The end and the means exist in relational tension to one another and to all the essential aspects which make up the circumstances. Principles for Determining Morality The three points of reference for determining the morality of human action, the physical act—in—itself (the object of the act, the means). the intention (end), and the circumstances (which include the consequences). Morality of the Act When we forget that the act-in-itself, the intention, and the circumstances are three aspects of one composite action. then we too easily make moral evaluations of any one part without considering the whole. 1. This gives us either an “act—centered” morality which forgets the person acting in a context (intention and circumstances). 2. Or an “intentions only” morality which does not take seriously enough the act being done. 3. Or a “situationalism” which maintains that circumstances make all the difference. The Moral Act The habit of timely, principle centered action in service of the other with preferential option for the most vulnerable with the intention of love (agape) as Jesus loved. Virtue For Aristotle Virtue is the state of experiencing the passions and acting: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. at the right time with reference to the right objects towards the right people with the right motive in the right way "virtue" (arete) = excellence in fulfilment of a particular function The Moral Act As a Habit The Moral Act As a Habit As a Guiding Principle of life The Moral Act As a Habit As a Guiding Principle of life As the Foundation of Character Sources • Kreeft, Peter. Ethics: A History of Moral Thought Course Guide, • http://download.audible.com/product_related_docs/BK_RECO_00216 8.zip • Gula, Richard M.. Reason Informed By Faith: Foundations of Catholic Morality. New York. Paulist Press. 1989. • Hamel. R.P. & I-limes. KR. Introduction to Christian Ethics: A Reader. New York. Paulist Press. 1989. Suggested reading • Kreeft, Peter. Philosophy 101: An Introduction to Philosophy. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2002. • Kreeft, Peter. Back to Virtue: Traditional Moral Wisdom for Modern Moral Confusion. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1997.