Chapter 2 - RUN - Universidade Nova de Lisboa

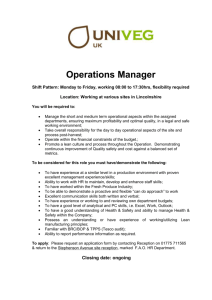

advertisement