Do I Matter to my Dad? The role of adolescent attributions.

advertisement

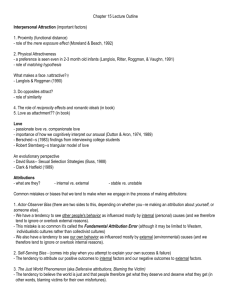

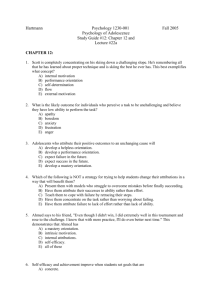

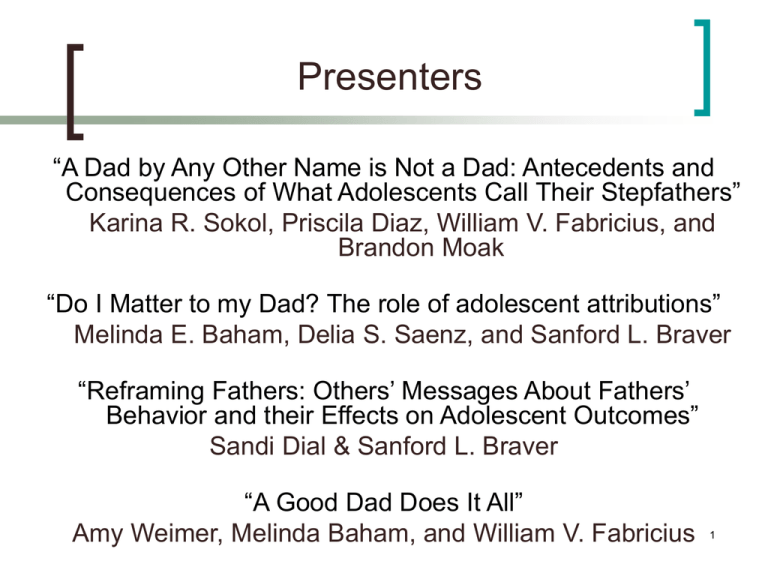

Presenters “A Dad by Any Other Name is Not a Dad: Antecedents and Consequences of What Adolescents Call Their Stepfathers” Karina R. Sokol, Priscila Diaz, William V. Fabricius, and Brandon Moak “Do I Matter to my Dad? The role of adolescent attributions” Melinda E. Baham, Delia S. Saenz, and Sanford L. Braver “Reframing Fathers: Others’ Messages About Fathers’ Behavior and their Effects on Adolescent Outcomes” Sandi Dial & Sanford L. Braver “A Good Dad Does It All” Amy Weimer, Melinda Baham, and William V. Fabricius 1 Naming, framing, and blaming: How adolescents construct their fathers Chair: Presenters: Delia Saenz, Ph.D. Priscila Diaz Melinda Baham Sandi Dial Amy Weimer Arizona State University 2 Parents & Youth Study: PAYS Arizona State University: Sanford Braver, Ph.D., Bill Fabricius, Ph.D., Toni Genalo, & Karina Sokol UC-Riverside: Scott Coltrane, Ph.D., Ross Parke, Ph.D., & students San Francisco State University: Jeff Cookston, Ph.D. 3 Parents & Youth Study: PAYS Funded by NIMH, NICHD Research foci: Role of fathers in adolescent development Mediators that predict the effect of fathers’ behavior on adolescent mental health and academic outcomes Variations in family characteristics (culture, intact vs. step-families) 4 Parents & Youth Study: PAYS 5-year longitudinal study Target participants are adolescents in transition from middle school to high school 2 sites: Phoenix, AZ & San Bernardino, CA 200 families per site (final n = 393) 5 PAYS Demographics 49% of the sample Mexican American 45% step-families (child, bio mom, stepdad) 52% girls 12.5 years mean age (range 11-14) $40K modal income (4.2K to 430K) 6 PAYS Methodological Approach Interviews with target child, biological mom, father/stepfather 3 Waves of data collection Wave 1 (2004) 2-hour in-home interviews Wave 2 (2005) 90-minute phone interviews Wave 3 (2006-) 2-hour in-home interviews 7 Social constructions of fathers Role of labeling Role of attributions Use of reframing Impact of normative fathering patterns 8 9 A Dad by Any Other Name is Not a Dad: Antecedents and Consequences of What Adolescents Call Their Stepfathers Karina R. Sokol, Priscila Diaz, Brandon Moak, & William V. Fabricius, Ph.D. Parents and Youth Study (PAYS) Arizona State University April 29, 2006 10 Overview Introduction Method Measures Hypotheses Results Why study stepfathers? Social Construction of Stepfathers Research questions Antecedents Consequences Discussion 11 Why Study Stepfathers? Almost 1/3 of children will have stepfathers sometime in their life (e.g. Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2000) Recent research reveals that adolescents in stepfather families are at a higher risk for mental health disorders and behavioral problems (e.g. Bray, 1999) 12 Social Construction of Stepfathers Cognitive, category-based judgments (Moshman, 1998) Parental identity and status (e.g.,Marsiglio, 2004) Parental claim or investment (e.g., Hofferth, 2003) Parental role (e.g. Fine, 1998) 13 What is in a name? “First of all, what do you call him?” Familial labels Significance of language 14 Research Questions What are the relationship and contextual variables that predict what adolescents call their stepfather? What are the differential outcomes between adolescents who refer to their stepfather as “Dad” versus those who do not? 15 Measures- Antecedents Contact with Bio Dad Years lived with Stepfather Response scale of 1(No contact in the past three years or more) to 7 (Contact almost everyday) Measured in years, range= 1-14 Overall Relationship with Stepfather (α = .79) e.g. “How well do you get along with your stepdad?” Response 1(Not well at all) to 5(Extremely well) 16 Measures- Consequences (Adolescent) Adolescent report of Externalizing Behavior (α = .82) Modification of Behavior Problems Index (8 items) e.g. “In the past month you argued alot.” Response scale 1 (not true), 2 (Somewhat true), 3 (Very true) 17 Measures- Consequences (teacher) Teacher Report of Behavior Problems Single items 1) “How often have you talked with this child about behavior, psychological, or emotional problems? Response scale 1(Never) to 4 (More than 5 times) 2) “Have you ever spoken to your Principal or Vice principal about this child’s emotional, psychological, or behavior problems? 3) “If all the students who are in the same class were asked about this child, would the MAJORITY of them say that this child is always getting into trouble?” 1 = No, 2 = Yes 18 Hypotheses- Antecedents Contact w/ Bio Dad _ Years Lived w/ Step-dad + “DAD” + Relationship w/ Step-dad 19 Hypotheses- Consequences _ _ “DAD” Externalizing Spoke w/ Child _ _ Spoke w/ principal Peers 20 Method of Analysis Results were ONLY on stepfamilies N = 140-175 Antecedents Logistic Regression Three variables Consequences One way ANOVA Adolescent externalizing Teacher behavior problem items 21 Results- Antecendents Overall model significant 2 (3) = 27.52, p < .001, Nagelkerke R2 = .25 Predictor B p Odds Ratio Contact w/ Bio Dad -.18 .05* 1/.84=1.19 Years lived with Stepfather .16 .023* 1.18 Overall Relationship .45 < .001*** 1.56 *p<.05 **p<.01 ***p<.001. 22 Classification Analysis Predicted “Dad” “Other” PC “Dad” 71 25 74 “Other” 12 32 72.7 Observed PAC = 74% Sensitivity Specificity 23 Results- Consequences Trend for those who called their stepfather by “dad” had less externalizing behavior (reported by adolescent) p = .079 Trend for those who called their stepfather by “dad” were on average talked to less about their behavior problems by teachers p = .076 24 Teacher spoke with principal Principal 1.12 1.08 1.04 1 0.96 Dad Other What you call your stepdad p = .019 25 Peers believe always in trouble (teacher report) 1.24 Peers 1.16 1.08 1 0.92 Dad Other What you call your stepdad p =.011 26 Discussion What adolescent calls stepfather is determined by context and relationship Provides evidence that the label “DAD” has important implications for adolescent behavior problems Future research will allow us to explore how they might predict other adolescent outcomes Further exploration of familial labeling is meaningful 27 Thank you! 28 29 Do I Matter to My Dad: The Role of Adolescent Attributions Melinda E. Baham, Delia S. Saenz, & Sanford L. Braver Arizona State University 30 Fathers are Important 31 Fathers have traditionally been understudied Fathering makes a substantial difference in child outcomes over and above the influence of mothering An aspect of the father-child relationship that deserves further study is how much the child feels he/she matters to his/her father What is Mattering? 32 Mattering involves the idea that a person is important to, and is cared about by, another individual Mattering to one’s parents relates to levels of self esteem, depression, anxiety, and overall wellness in adolescents Mattering to parents and friends explained differences in self concept and behavioral misconduct in adolescents What matters to mattering? 33 Since mattering to others is highly predictive of important child outcomes, this leads to the question: How does this sense of mattering arise? The majority of mattering research to date examines the impact of mattering as a predictor for various outcomes We wondered: When mattering is viewed as an outcome, what psychological phenomena influence mattering? Reasons Given for Behaviors 34 One potential explanation of how a child determines that he matters to his father might be the reasons a child gives for his father’s behaviors For example, imagine a child’s father works long hours One child might say his father works all the time because his father doesn’t care about him Another child might say her father works all the time because her father cares for her so much that her father works long hours These reasons, or attributions, may influence the child’s perceived mattering to his father Attributions 35 Attributions are the reasons that people give for various events and behaviors Attributions answer the “why” questions Attributions are made about a wide variety of behavioral events, but the attributions themselves vary along only a few causal dimensions Our focus is Stability - is the attributed cause of the behavior stable or unstable? Children’s Attributions of Parents 36 Few studies have examined children’s attributions of parent behaviors One study found children’s stable (among other) attributions of negative parent behaviors were negatively correlated with positivity in the parent-child relationships Also, the more a child endorsed stable attributions of the father’s negative behavior, the less positive the observed interaction between father and child Other studies report children’s stable attributions of negative parental behavior related to ineffective communication between the child and the parent Types of Attribution-Eliciting Events 37 When considering the behavioral events that participants are asked to make attributions about, two questions emerge: Are the events real or hypothetical? Are the events positive or negative? Very few studies have included positive events, and even fewer studies included events that were real The Present Study This study had several aims: To investigate aspects of the father-child relationship, specifically mattering To investigate what factors may lead to mattering To elicit attributions made about real events, and about both positive and negative behaviors To determine if adolescents’ attributions of fathers’ behaviors significantly predict mattering 38 Hypotheses Stable Positive Attributions Unstable Positive Attributions Stable Negative Attributions Unstable Negative Attributions 39 + ? Mattering ? Measures - Mattering Questionnaire 40 Adolescents responded to how much they agree each statement describes their relationship with their father on a 5 point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) 7 items were added in order to create one variable that measures overall feelings of mattering, where the higher the value, the more one feels he matters (minimum score of 7, max. score of 35) This scale has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .86) Mattering Questionnaire Items Sample Items: My [dad/step-dad] really cares about me. I believe I really matter to my [dad/stepdad]. I know my [dad/step-dad] loves me. I am one of the most important things in the world to my [dad/step-dad]. 41 Measures - Attribution Questionnaire 42 Adolescents were asked to think of a time their father did or said something nice, and a time he did or said something mean After each behavior, adolescents were asked to rate how much the behavior was due to several reasons on a 1-5 scale, where 1 was not at all the reason, and 5 was exactly the reason The reasons were designed to tap the causal dimension of stability Reasons for positive behavior Stable He’s a positive or nice kind of person? He likes to make you happy? He cares about you? Unstable You really deserved it? He happened to be in a good mood? Someone else told him to or wanted him to? 43 Reasons for negative behavior Stable He’s a mean or difficult person? He’s ALWAYS down on you? He doesn’t care if something he says bothers or hurts you? Unstable You really deserved it? He happened to be in a bad mood? It was just one of those times that he really got upset? 44 Data Reduction of Attribution Measure Four new variables were created: 45 The extent to which a child endorsed stable causes for any type of positive father behavior The extent to which a child endorsed unstable reasons for any type of positive father behavior The extent to which a child endorsed stable causes for any type of negative father behavior The extent to which a child endorsed unstable causes for any type of negative father behavior Results 46 Of the 393 adolescents who participated, 27 adolescents could not think of examples of their fathers’ behaviors (either verbal statements or behavioral actions), thus the final sample consisted of 366 adolescents. 47 Mean Standard Deviation Stable Attributions for Positive Behaviors 4.28 0.70 Unstable Attributions for Positive Behaviors 2.76 0.61 Stable Attributions for Negative Behaviors 1.57 0.72 Unstable Attributions for Negative Behaviors 2.50 0.76 Mattering to Father 31.40 4.53 Primary Analysis 48 Investigated if the extent to which adolescents endorsed stable and unstable attributions for positive and negative events could predict perceived mattering to fathers A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted in which the two positive attributions were entered as the first block, and the two negative attributions were entered in a second block to predict mattering This allowed for a direct comparison of how attributions about positive behaviors and attributions about negative behaviors potentially differentially impact mattering Results of Primary Analysis The four attribution variables significantly predicted perceived mattering to father, F (4, 361) = 81.60, p < .001, and accounted for 47.5% of the variance 49 Regression Intercept Standardized B BETA 23.92 t 16.28*** Stable positive attributions 2.95 0.46 9.79*** Unstable positive attributions -0.46 -0.06 -1.45 Stable negative attributions -2.14 -0.34 -7.10*** Unstable negative attributions -0.20 -0.03 -0.83 R Square *** p < .001 50 Unstand. .48 Results of Primary Analysis con. 51 The stable and unstable attributions for negative behaviors significantly added to the prediction in mattering over and above stable and unstable attributions for positive behaviors, F (2, 361) = 29.86, p < .001. A second hierarchical OLS regression analysis found that attributions for positive behaviors account for variance in mattering over and above variance accounted for by attributions for negative behaviors, F (2, 361) = 50.31, p < .001. Discussion 52 The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between the attributions adolescents make about their fathers’ behaviors and the adolescents’ perceived mattering to their fathers Overall, the results of the study support the hypotheses. As adolescents increased their endorsement for stable attributions for positive father behaviors, the more they perceived they mattered to their fathers As adolescents increased their endorsement for stable attributions for negative father behaviors, the less they perceived they mattered to their fathers These findings suggest a partial explanation for how feelings of mattering to one’s father might come about Discussion continued 53 This study illustrates that differences in mattering can be explained by attributions of fathers’ behaviors, Stable attributions about either positive or negative behaviors explain much more about mattering than do unstable attributions Positive attributions had a slightly stronger relationship with mattering than did negative attributions Both positive and negative attributions uniquely contributed to predict mattering Highlights the need to include both positive and negative events when eliciting attributions Future Directions 54 Continue using positive and negative behaviors to elicit attributions, and focus on positive outcomes, such as perceived mattering to fathers Further exploration of the causal direction of attributions, of gender differences, and of ethnicity differences are warranted THANK YOU! 55 56 Reframing Fathers: Other’s Messages About Fathers’ Behavior and Their Effects on Adolescent Outcomes Sandi Dial & Sanford L. Braver, Ph.D. Arizona State University 57 Overview Existing definitions of reframing Reframing in the Literature Reframing as defined by PAYS Measures Descriptions Research Questions and Results I. II. III. IV. V. I. II. III. VI. Research Question 1 and Results Research Question 2 and Results Research Questions 3 and Results Discussion 58 Reframing Reinterpreting or reappraising a situation Generally conceptualized as a positive process 59 Reframing and Children in the Literature Maternal reframing was found to mediate parenting stress and attachment with infants (McKelvey, 2004) Maternal use of reframing viewed more positively by sons compared to paternal use of reframing (Kliewer, et al., 1996) 60 Reframing in the Current Study The nature of messages mothers, fathers, and non-parents provide to an adolescent and s/he is upset or bothered about the relationship to the (step-)father or about the things he says or does This definition will possibly allow the current study to answer questions raised by past researchers Thought to be generally beneficial 61 Outcome Measures Mother and father report of internalizing and externalizing adapted from Behavior Problems Index (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Peterson & Zill, 1986) Child report of externalizing adapted from Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Peterson & Zill, 1986) Child report of internalizing a mean of standardized scores from questions adapted from the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1979; Reynolds & Paget, 1981) – Moderate reliability (α =.65 and .67 respectively) 62 Outcome Measures Mother, father and child report of fatherchild relationship from the Overall Relationship Quality Scale – 2-item scale assessing how well father and child get along 63 Research Question 1 How are the characteristics of reframing correlated with the adolescent’s outcomes? Characteristics of reframing: – – – – Frequency of reframing Frequency of a reason given Type of reframe (e.g., criticize vs. support) Child’s feelings about the father and relationship with him after reframing – Child’s feelings about self after reframing Outcome Measures – Internalizing behaviors – Externalizing behaviors – Father-child relationship quality 64 Patterns of Results for Correlations Many significant correlations Nearly all significant correlations were in expected directions, i.e., reframing enhanced adolescent well-being – Correlation of mother’s frequency of giving a reason for father’s behavior with father’s report of adolescent externalizing (r = -.20, p < .01) – Correlation of adolescent’s feelings about father after mother’s reframe and adolescent’s report of father-child relationship (r = .31, p < .01) Largest correlation (r = .43, p < .01) was between non-parent’s support of father and adolescent’s report of father-child relationship65 Research Question 2 How do the types of reframes given by mothers about the (step-)father’s behavior compare to the reframes given by fathers? If there is a difference, what effect does this difference have on the relationship quality with the father as well as the adolescent’s outcomes? 66 Parental Differences in Reframing Fathers Means Reframing Question Mother Father F How frequently do you talk to this person about your (step-)father’s behavior? 4.54 4.56 .01 How frequently does this person give you a reason for your (step-)father’s behavior? 5.26 5.39 .98 Does this person criticize or support your (step-)father’s behavior? 3.20 2.23 58.75** How do you feel about your (step-)father after this person reframes his behavior? 4.03 4.09 .59 How do you feel about yourself after this person reframes your (step-)father’s behavior? 3.82 4.00 4.20* 67 Moderation Plot for Research Question 2 Child's Report of Externalizing Behavior 17 Father Apologizes 16.5 Father Equal Apologizes and Defends Himself 16 Father Defends Himself 15.5 15 14.5 14 13.5 13 12.5 1 2 3 4 5 Mother's Reframe of Father's Behavior: Low = Criticize, High = Support 68 Research Question 3 Is there a difference in the reframes afforded to children in stepfamilies versus intact families? 69 Fisher’s r-to-Z Comparisons of Correlations by Family Type Reframing Variable Outcome Variable Reporter r for intact r for step Zdifference Feelings about father after mother reframe Externalizing Father .01 -.24 2.13* Feelings about self after mother reframe Externalizing Child -.05 -.28 1.95* Feelings about father after mother reframe Father-child relationship Child .10 .48 -3.46*** Frequency of reframing by father Father-child relationship Father -.05 .45 -3.19*** 70 Discussion Reframing is generally beneficial Adolescents in stepfamilies should be encouraged to seek out reframing Future research should aim to identify the specific content of reframes and how that content affects outcomes 71 72 A Good Dad Does It All Amy A. Weimer, Melinda E. Baham, and William V. Fabricius Arizona State University 73 Overview • Introduction – Research questions • Method – Measures 1. Behavioral Evidence 2. Relationship Scripts • Results – Relationship between Behavioral Evidence & Relationship Scripts • Discussion & Conclusions 74 Purpose • To assess the child’s view of father-child relationships through two unique measures: 1) Behavioral Evidence 2) Relationship Scripts 75 Introduction • Fathers are important to adolescents’ behavioral and mental health outcomes • Research is needed to assess the quality of father-child relationships among Mexican- and Anglo-American step and intact families 76 Research Questions 1) Are there different dimensions of father behaviors, or do dads do it all? 2) Do scores on objective measures correlate with open-ended qualitative measures of parent-child relationships? 77 Method 1) Behavioral Evidence: survey measure asking adolescents how often their (step)father provides “behavioral evidence” that he considers them important in his life 2) Relationship Scripts: open-ended questions prompting children to tell us “the story” of their relationship with their father, using their own words 78 1. Behavioral Evidence • Developed for PAYS project to assess the actions of father/stepfathers toward their adolescent child • Responses ranged from 1 to 5, on a 5-point scale, from Never to Very often • Summed scores had good reliability: Alpha = .94 • Higher scores indicate fathers more often displayed positive parenting behaviors 79 Sample Items on Behavioral Evidence measure: How often does dad . . . • spend time with you? • listen and talk with you? • do fun things? • listen to your side of the argument? • hug you, pat you on the back, or show other signs of physical affection? • encourage you to feel better when you're feeling upset? • give you money and/or other things? • act interested in you or what you have to say? • help you when you need help? 80 Results: Behavioral Evidence Frequency of Positive Parent Behavior Mean Differences by Family Type & Ethnic Group 94 92 90 88 86 84 82 80 78 76 74 Mex-Am Anglo-Am Step Family type Intact Main effects of family type and ethnic group, but no interaction effect (controlling for SES) 81 Collapsed across family type & ethnic groups Children’s average response was “3” indicating that on average all dads “often” engaged in positive behaviors 82 How related are items on Behavioral Evidence Measure? • A single underlying factor explained most (52%) of the variance observed among the 22 Behavioral Evidence items • Suggests that dads “do it all” 83 2. Relationship Scripts • Children produced rich, script-like descriptions about their relationship with father or stepfather • Three themes appeared in almost every child’s script: (1) Investment (IN), the child’s evaluation of the time and energy the parent invests in the relationship (2) Emotional quality (EQ), the positive versus negative emotions the child feels toward the parent relationship (3) Responsiveness (RE), the child’s evaluation of the parent’s responsiveness to needs or requests (4) Provisioning (PR), the child’s evaluation of how good a provider or source of financial support the parent is 84 Coding Scripts • Qualitative data was quantified on these 4 dimensions 1. Parsed into smallest meaningful statements 2. Identified dimensions the statement was about, if any 3. Rated dimensions of statements as low, medium, or high • Interrater reliability was calculated by correlating 6 coders’ average scores on 60 scripts, coded by PAYS researchers. Reliability was acceptable: • IN =.91, EQ = .94, RE = .84 85 Sample Relationship Script [My father] is one of those people who likes to do things for others, who is very nice (EQ3) // and respectful (EQ3) // and he is just a good person (EQ3). // If I have a problem, like he will be the one who will sit down and talk to me about it (RE3), // and he talks to me in a nice way (EQ3, RE3). He helps me sometimes with things (RE2) // and even when he is busy, he will take time for me (IN3). 86 Results: Relationship Scripts Intercorrelations Among Dimensions Investment Investment Emotional Quality Responsiveness 1.0 Emotional Quality Responsiveness .41** .25** 1.0 .41** 1.0 ** p < .01 87 Dimension Ratings by Family Type and Ethnic Groups Average Dimension Rating 2.9 2.8 2.7 2.4 MA Intact AA Intact MA Step AA Step 2.3 IN = Investment 2.2 EQ= Emotional Quality 2.6 2.5 IN EQ RE RE = Responsiveness Marginally significant main effects of family type (controlling for SES): Intact families (blue) > Stepfamilies (red) RE, p=.06, IN, p= .07 88 Results: Relating Behavior Evidence to Relationship Script Dimensions: • Mean scores on Behavioral Evidence positively correlated with dimensions of children’s relationship scripts: 1) Investment r = .44 2) Emotional quality r = .50 3) Responsiveness r = .40 89 Discussion 1) Are there different dimensions of father behaviors, or do dads do it all? • Single Factor on Behavioral Evidence • Suggests that dads are involved in many aspects of child rearing. 2) Do objective measures correlate with open-ended qualitative measures of parent-child relationships? • Suggests validity of measures • Good dads (dads who children perceive as spending more time and energy, providing for emotional comfort, and who respond to their needs) participate in many parenting behaviors 90 Limitations & Future Research • First wave of data only • Used self-identified ethnic groups (could examine based on continuum of cultural values) • Could compare to mom 91 Conclusions • Have developed two promising new measures of adolescent relationships with their fathers • Demonstrated that fathers participate broadly in child rearing behavior • Shown that these behaviors relate to how child feels about him 92 Thank You 93