Master Thesis...neurship - Lund University Publications

advertisement

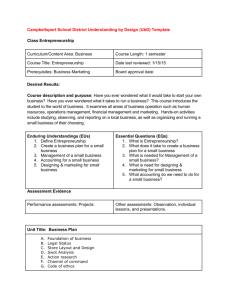

The immigrant status does not explain individual immigrant entrepreneurial paths. General entrepreneurial skills take over while identifying opportunities and progress in business. Ronny Elovsson Pooya Jahankhah MASTER THESIS IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP (MSc) 2013-05-20 Tobias Schölin & Diamanto Politis 0 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Immigrant Entrepreneurship – Literature review .................................................................................... 5 2.1) The Kloosterman model of mixed embeddedness ....................................................................... 5 2.2) Motivational factors ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.3) Experience, background and culture ............................................................................................ 8 2.4) Refugees and other remaining immigrants .................................................................................. 9 Method and procedure for the study ........................................................................................................ 9 3.1) Design ......................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2) Selection of respondents ............................................................................................................ 10 3.3) Data collection ........................................................................................................................... 10 3.4) Analysis method......................................................................................................................... 10 3.5) Respondents interviewed………….……………………………………………………………11 3.6) Limitations………………………….…………………………………………………………..11 The Entrepreneurial immigration Theory of Science up to the point of mixed embeddedness including analysis…………………………………………………………………………………………………12 4.1) Summary Interviews .................................................................................................................. 12 4.2) Vacancy chain opening (Market B) ......................................................................................... 133 4.3) Post industry/low skilled (Market C) ....................................................................................... 155 4.4) Post-industrial/High skilled Market (Market D) ...................................................................... 167 4.5) Motivation ................................................................................................................................ 177 4.6) Culture and Background .......................................................................................................... 188 4.7 Entrepreneurial skills ................................................................................................................... 19 4.8) Refugees ..................................................................................................................................... 20 5) Discussion ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Cited works ........................................................................................................................................... 22 1 Abstract In this qualitative study we aim at identifying if a refugee verses other immigrants take different paths in their entrepreneurial efforts as migrants. We used a qualitative multi case method based on semi conducted interviews within the Persian community, immigrant entrepreneurs in Sweden. A revised model of Kloosterman´s mixed embeddedness was used for the communication of the empirical findings (Kloosterman, Leun and Rath, 1999; Kloosterman, 2010). With the research question: How does the establishment of entrepreneurial self-employment look like for refugees (according to the UN definition including quote refugees) respective to the other groups of foreign origin (according to SCBs definition)? Do the refugees, remaining in Sweden, with entrepreneurial self-employment, differ from other immigrants, particularly within their identification of opportunities as entrepreneurs, and if so in which ways? We found no evidence that there should be any differences in the entrepreneurial opportunity depending on the immigrant’s status. Instead general human capital, entrepreneurial experience and adaptability to change including macro level changes are identified as explanatory factors for the immigrant entrepreneurial paths. The result questions, one part of Kloosterman’s research, specifically related to the locked in effect among the entrepreneurs. Background Imagine yourself being an entrepreneur, interrupted and forced to leave everything you built up, behind you. Then you enter a new country, as an immigrant entrepreneur, in an environment which you might not know anything about. The paths to take for those individual entrepreneurs may differ for several reasons. In this study we aim at immigrant entrepreneurs and the individual behavior in the new settlements, particularly related to refugees and other immigrants. One reason to lift up immigration is that approximately 3% of the world’s Population-Immigrants account for 10% of the population living in developed countries e (Riddle, 2008). Immigrants are further a group that is affected by the transition into the market economy. According to Dahrendorf (1991) referred to by Donald and Landström (1999) the transformation process in European countries in transition can be analyzed by three different factors: politics, economy and society, which leads to political, economic and social transformation. The immigrant entrepreneurs, also part of the transformation and the effects of their entry to a third country changes over time. Previous research show different views. Initially the culturist view state that specific immigrant groups share solidarity including specific skills for success in business. This view was particularly used by 2 Glazer (Glazer, 1955). In the second- ecological view, two streams can be seen. On the one hand by comparing modern economy and the economy of the Small Business class. In addition search for patterns of spatial order including residents, neighbors and then the small business class according to Aldrich. (Aldrich, 1975) With this view businesses are only open when there are offers for jobs and services, dependent on the action from the majority in the market. Recent research conducted by Kloosterman (2010) rice the need of immigrant entrepreneurship, at the intersection of changes with socio cultural frameworks on the one side and transformation processes on the other side. In this context, the two sides, referring to the supply side of the entrepreneur on the one hand and the demand side, the changed market conditions, on the other. Then the interplay of changes within those two sides becomes part of a larger dynamic framework of institutions on several levels range from neighborhood, city, national and economic. The opportunity factor within the mixed embeddedness view is quite important. This is due to the fact that market conditions to a very high extent affect the specific segments where openings occur according to Kloosterman (2010). Therefor we will use a revised model of Kloostermans (2010) opportunity model based on the theory of mixed embeddedness. By using various factors, including motivation we further explore the immigrant entrepreneurs entering Sweden and in particular the relation between refugees and other immigrants. The term refugee here is defined according to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Statues of Refugees-UNHCR (UN, 2013) summarized: any person in fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that original country. (UN, 2013) By getting a higher awareness of the process in becoming an immigrant refugee entrepreneur tools and information can be developed and improved in order to ease up the process and in such case making the communication for immigrant entrepreneurial goals more efficient. How does the establishment of entrepreneurial self-employment look like for refugees (according to the UN definition including quote refugees) respective to the other groups of foreign origin (according to SCBs definition)? Do the refugees, remaining in Sweden, with entrepreneurial self-employment, differ from other immigrants, particularly within their identification of opportunities as entrepreneurs, and if so in which ways? Here one can think that it might take more efforts, becoming an entrepreneur as a refuge for the basic reason that adapting to a new culture which is not individually chosen is more time consuming for various reasons. However it might be easier to adapt to an entrepreneurial environment if you have previously had a business background from your original country. In addition the influence and support from a big 3 family up to the level of cousins and siblings may in addition have positive effects on a startup entrepreneur. But on the other hand, it might be that a big family may have negative impacts in adapting to a new society. After all, the macro level factors also matter in some cases according to Kloosterman (2010). The area is specifically important as self-employed immigrants may end up in a steady increased informal market, a market that may not function so well. Kloosterman has identified (1999, 2010) these markets as part of the mixed embeddedness model. On an individual level those immigrants may get embedded, unconsciously in an underpaid employment or self-owned business without profit or growth potential. And further companies operating in those informal markets may create uneven competition to the formal markets by not following labour laws or other regulations. Therefore, we aim at reviewing the behavior relating to how and why opportunity and necessity openings occur as parts of the motivational effects (1). We take into consideration the previous entrepreneurial experience, (2) the immigration status (3) and finally include the cultural/social/human to the model (4). With those factors applied to Kloosterman’s (2010) opportunity model we hope to find patterns to assess if there are differences in entering a new market depending on the immigrant´s status. We use Kloosterman’s (2010) opportunity model, because we need to consider the influence of both the individual and the external effects on the entrepreneurs. Kloosterman’s model (2010) does take into account both macro and micro perspectives as part of the opportunity or necessity development of the entrepreneurs. But critics have merged from the original model of mixed embeddedness, as it did not include micro level effects from the beginning. In addition Razin (2002) criticizes the mixed embeddedness model for being both fuzzy and in many cases hard to validate empirically. Case studies demonstrate various aspects of the economic milieu that influence immigrant enterprise and provide some evidence for the embeddedness and mixed embeddedness concepts, but not the need for a broader and more formal verification of claims based on these structures. In Kloosterman’s (2010) opportunity model we have also identified that the factor human capital can be misleading, particularly since it’s a very broad term. Kloosterman has not really defined his use of human capital neither in the original Kloosterman (1999) model nor in the opportunity model Kloosterman (2010). Therefore we have used a revised model, where we exchange the human capital factor in the model with motivation, entrepreneurial skills in addition to background and culture. By doing so we would clearly focus on individual effects relating to opportunity identification. In addition human capital as a 4 factor may vary in interpretation from competencies, general knowledge, being specifically gifted, social and other personal attributes, which clearly is not so precise. Lastly, to sharpen our result, we targeted the Persian people, from the south of Skane County (Sweden) in who have migrated from Iran and speak the modern Persian Language. (Wikipedia, 2013). 2) Immigrant Entrepreneurship – Literature review The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, referred to as GEM (2013) consortium collects and analyses entrepreneurship related research-quality data. The measures of national and regional entrepreneurial behaviors and activities first used in the GEM (2013) project have been the Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) Index that focuses upon new business creation rather than self-employment. The definition of TEA refers to entrepreneurial activity including both starting up and running new businesses, up to 3.5 years after the start. The measures include adults between 18-64 years of age according to Braunerhjelm et al. (2012). Entrepreneurial activities in Sweden have increased in the past year (2012) with 18% and in an overall European measure Sweden ranks in the lower half of the comparable European countries. (GEM, 2013) The studies that are conducted on entrepreneurship out of necessity, identified within the GEM (2013) model, show that those entrepreneurs, who have lower education and run smaller firms, expect their firms to grow less. Nevertheless, despite these factors they are more likely to still remain in the market (Poschke 2013). 2.1) The Kloosterman model of mixed embeddedness The reason for using this model is lying in the thoroughness in delivering a multidimensional mixed embedded model. On the one hand, the model takes into consideration the influence of individual resources and cultural structure (micro level) as a reason for initiating and progressing within the entrepreneurship. On the other hand, external factors that influence the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition of the individual such as legislation, politics and economics (macro level) are combined into the model. Taking micro and macro level influencing factors into consideration, two phenomena follows. It may on the one hand, create opportunities for the right entrepreneurs with the right resources to merge. On the other hand, it may force upon the entrepreneurs, embeddedness within a certain market condition with little or no growth opportunity, the so-called locked in effect. Kloosterman (2010) uses two main dimensions in order to integrate the micro and macro perspectives, here identified as the Individual capital and the market growth. With such structure, four distinguished market conditions are formed (A; B; C; D). All the four market conditions in this model are different in that, if the entrepreneur’s initiatives are opportunity or necessity driven. 5 The model shall be seen as if there is an underlying opportunity (to identify) to strive for moving towards the right top corner. In Figure 1, background and culture, motivation and entrepreneurial skills are presented under the title of Total individual capital. The original Kloosterman model (2010) uses only Human capital within this dimension as we previously mentioned. The fundamental dimensions of the model here consist of total individual capital and the market growth, which are the main influencing factors on the market conditions. With further elaboration on each market condition, the matter is clarified further. In our view Human capital is addressed in a very broad sense when it comes to entrepreneurial behavior. As we intend to study the entrepreneurial behavior relating to the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition, we intend to use the Kloosterman (2010) opportunity model in a revised version. In this regard, the Human capital measures are broken down to a more direct measurement of features that are influencing the entrepreneur directly. The revised version is referred to as total individual capital and it consist of individual motivation, entrepreneurial skills and background and culture. The model is used, in order to identify, what markets our respondents enter a certain market and how they progress. Here, we look both on the national level, with regulations and politics as well as the local level, referring to family, friends and neighborhood influence. Below follows the markets identified and categorized by Kloosterman´s (2010) opportunity model based on the mixed embeddedness. The high skilled stagnating sector (upper left module named market A) can be considered not as attractive for high skilled staff as it’s a stagnating market. Kloosterman (2010) therefore leave this market without analysis, which this study also does. Figure 1: Revised model of Kloosterman (2010) 6 The vacancy chain (Market B) here refers to markets which in general are mature but with limited or no growth opportunity. In this window the entry barriers are low for immigrants in terms of entering as new immigrants. Recruitment is also progressing within the window as long as new immigrants are ready to take over. This vacancy market does not take much investment to enter and regarding individual human capital it includes limited skills of the new market (Kloosterman, 2010). The vacancy chain process here refer to the fact that the most motivated entrepreneurs leave the most low played opportunities and try to climb the ladder for more prospers business, in turn leaving new opening for other newcomers Waldinger et al.(1996). The Post-industrial /Low skilled market (Market C) has one big difference compared to the previous market window that is the growth opportunity in these markets. With a fairly low skilled individual demands, the entry barrier is still low. For entrepreneurs, with certain skills for innovation it’s a perfect market to enter as a newcomer from developing countries. In these markets one can find a business within the early phases of a lifecycle or also new markets such as various services (Kloosterman, 2010). There is also a difference in the sociability. Adapting to new networks and identify potential customer groups specifically outside the individual´s ethnicity, is important in order to succeed in this category according to Kloosterman (2010). In the Post- industrial /high skilled market (Market D) Academic studies, high social competence and a vision for opportunity are factors necessary in order to succeed within this market, hence the threshold level is quite high. The market is fast and rapidly growing, much due to the global free market in a macro perspective, where movement of capital, resources and skill is expanded between countries.in this market we can see, many well educated students from outside OECD countries, including Chinese and Indians (Kloosterman, 2010). There are many technical firms, innovative firms within this market. On the individual level it’s a very heterogeneous group which ad values to each other’s networking. In each one of the markets the first steps are driven by either need or opportunity identification. 2.2) Motivational factors The word motivation does not have a single accepted definition, according to the nature of phenomenon. But in general motivation includes direction-how to perform, efforts-how hard to reach that performance, and finally the persistence-how long one is trying before results are reached. After all, people do differ in motivations of becoming migrant entrepreneurs. Recent studies have shown that unemployment is one of the main motivations in initiating entrepreneurial inclinations among the immigrants (Reynolds et al., 2001). An opportunity too good to resist, a recommendation within family, monetary motives, freedom of being your own boss, social prestige and financial freedom are among the most motivating factors too (Husam, 2011). Looking at the matter from the nascent entrepreneur’s perspective, two of the earliest motivating factors are the desire to take risk and the 7 spirit of adventure (Knight, 1921) in addition to the desire to innovate (Schumpeter, 1934). Moreover, motives may also differ between genders where females strive mainly towards independence within the family in the developed world. Men on the other hand, are mainly influenced by job dissatisfaction (Kirkwood, 2009). Hence as explained earlier, the motivation in an immigrant entrepreneur can be triggered through variety of means. The Important perspective that is taken into consideration here is if these motivational factors are driven by necessity or opportunity. The necessity entrepreneur is more need driven whereas the opportunity entrepreneur is viewed as an entrepreneur who initiates a business in order to pursue a recognized opportunity. A voluntary pursuit of opportunity entrepreneurship should reflect the opportunity group and necessity entrepreneurship is referred to activities that occur in the absence of other employment possibilities (Reynolds et al. 2001). This definition will also be used in the current study. 2.3) Experience, background and culture In the previous chapter we discussed the difference in entrepreneurs’ motivations. On top of motivation the role of background in forming an appropriate entrepreneurial attitude is vital. Studies prove that background, culture and demographics have direct impact on success or failure (Byers, 1997). Moreover, Education and academic background compliment these factors. A study conducted by Davey et al. (2011) shows that developing economy students are more likely to imagine a western career with entrepreneurial ambitions than their counterpart in the western world. Even within the higher education students, there are studies showing differences for example technical students in Turkey who were more creative than humanities students (Qasemnezhad, 2012). Other recent studies also point at the likelihood of becoming an entrepreneur in a host country depending on whether you are brought up in urban or rural geographic locations. The results show that even origin-habitual factors relates to entrepreneurial activities (Bauder, 2008). However recent studies prove that, one can also see that the culture differs, both in terms of the culture within family and the social structure of the country of origin (Foreman & Peng-Zhou, 2013). Persistence and Strength in the culture were considered as main variables of whether or not entering into entrepreneurship. Immigrants and particularly non Europeans and refuges are particularly vulnerable upon entering new cultural markets (Green, Kler, & Leeves, 2007). Adapting to a new culture is not less important for an entrepreneur as he also has to adopt to a new market and in many cases a different business culture as well. A better understanding of a local culture helps the immigrants to feel more emotionally secure and by doing so faster and better adopting to the new culture (Deumert et al. 2005). Much of the different outcomes in these entrepreneurial efforts refer to the human capital of the individual entrepreneur, including his abilities and skills achieved in the past (Panayiotopoulos, 2006). 8 2.4) Refugees and other remaining immigrants There is little research conducted that covers the differences between refugees and other immigrants (economic, bound-pretending refugee motives) and their success as entrepreneurs in the host country. One way to describe some of the differences between those groups is a study in Political migration (Schaeffer, 2010). Here Schaeffer argues that refugees in most cases have a choice of staying, in political minority settlements and avoid the integration into host country. With pressure in nondemocratic countries, the longing for freedom and other democratic rights, forces them to take the decision to move. In the situations of war and ethnic cleansing people do not usually have a choice, but rather to grab what they can and fly for their lives due to the threat. Economic immigrants do not have to fly for their lives, they have a much larger freedom to plan and choose their path than other immigrant groups (Schaeffer, 2010). 3) Method and procedure for the study 3.1) Design We conduct an explorative qualitative case study by using a semi conducted interview method. We use a Multiple-design in order to enrich the study, covering a broad theoretical insight from previous research, combined with the respondents’ empirical data. The choice of multiple designs is taken, on the one hand to gain broader aspect from several respondents for replication and on the other hand to clarify both similarities and differences among the respondents. In addition, the study holds two broad dimensions, the refugees and other immigrants, where a multiple study would be necessary to identify similarities and differences, if any within the group. The first step was to develop the theory, where we initially used Kloosterman’s (2010) mixed embeddedness who combine both individual (micro) factors as well as factors, political and legislative factors (macro), explaining the various markets for immigrant entrepreneurs. 3.2) Selection of respondents Dealing with an ethnicity for entrepreneurs in many cases is a challenge, if you do not belong to such a network. But in this study we used a screening of an informal Persian network within the region of Skane County. With defined operational criteria for the screening we reached the goals for a proper formal data collection (Yin, Case Study Research, 2009). The selection criteria was 1) Persian 2) Entrepreneur 3) Either refugee or other immigrants 4) Within one region of Skane and 5) with current remaining business. The selected respondents came from an informal network within the Persian community. We paid extra attention both to find respondents within the main two criteria refugee and to other immigrants. With life stories from the respondents, we develop insight from the entrepreneurial experience during the analysis. We used them in a context of semi-conducted interviews, relating to the startup and development process of the respondents’ 9 businesses and their previous background from their home country. Further the transition to their new country and their progress within entrepreneurship, including skill improvement in their new country. 3.3) Data collection As we conducted a multiple case study, the first step was to develop the theory. With an initial pilot study our aims matched the initial developed theory and we continued with the original selection criteria. The interviews were recorded and transcribed directly after. In order to get the stories genuine, the interviews were held in Persian, and translated to English. After the first collection of the transcribed interviews, we initiated the analysis, applying the empirical results on the original theory. Evidence was sought regarding facts and conclusions from each case (Yin, Case Study Research, 2009). In addition considerations were taken to how and why replication occurred between the multiple cases. As important discoveries were developed we used theoretical feed-back loop (Yin, 2009) in order to further develop related theories. 3.4) Analysis method The analysis method used was according to Langemar (2010, s134). Initially we used open coding for each interview, reviewing all data from each case. We specifically looked for repetitive patterns within each case and there after both groups were compared. Special attention was paid to commonalities or differences between the two groups, if any. Relevant data from each case was then summarized. In the second stage we used selective coding within main categories (motivation, background, immigrant status, education, market entry, failure). At this stage we selected by judging the most repetitive expressions among the respondents within each category. We also interpreted where the market entry occurred according to Kloostermans (2010) market windows. In addition with each case we tried to identify the impact of macro and micro effects that may have benefited or limited the respondents in their opportunity identification. All data used are result of subjective measures. Self-experience interviews were made and the interpretations have been conducted from those interviews. In order to visualize the statements from respondents we then picked out representative quotes, statements that supported our findings. At this stage we coded relevant facts “quotes” within each category. In the third stage, we used theoretical coding, by applying characteristics of Kloosterman’s windows, on macro and micro level effects. Theories were used explaining additional results. In order to validate our findings we argued between the authors for the common results so the claims we made indicates reasonable interpretations of the results. A final aspect for validation was the data collection; the only relevant information was collected from the interviews. A critical analysis was also conducted both from previous theories and the results within the study (Langemar, 2010, p 108). 10 3.5) Respondents Interviews Demographics Farhad Behzad Mojgan Morteza Birth Age Sex Immigrant status Persian 46 Male Refugee Persian 55 Male Refugee Current business sector Firm size(staff) Years in Sweden Years in business (current) Education Failure experience Retailing(FMCG*) Services (Taxi) 52 23 16 12th grade Yes Persian 40 Female Other groups Technology Persian 56 Male Other groups Engineering 5 3 3 PHD No 15 20 10 Graduate Yes 3 26 3 Bachelor Yes Figure 2: Respondents demographics ‘(FMCG=Fast Moving Consumer Goods) 3.6) Limitations The study does include some limitations. Since we only use respondents within the Persian community we have limits in the demographics, which include different arrival dates into Sweden, different age groups and different educational levels. Therefore some of the findings have to be taken with precautious considerations. Further, when it comes to the identification of the opportunity recognition it includes various industries, in itself with different characteristics, indicating that market entry, opportunity recognition and operations are partly unique within each one of those industries. In addition the use of Kloosterman (2010) opportunity model has been criticized for its complexity and difficulty of validation. When it comes to the total amount of respondents we only used four. In that case, for individual response (micro level) we could identify repeated patterns. Nevertheless, Kloosterman’s four different windows make it impossible to trace repeated patterns with so few respondents in macro level, mainly because most respondents ended up in a different opportunity window. Finally in some of the cases, time from the action and the actual interviews are many years and in addition self-expressed by the respondents, and therefore the stories told may include inaccurate memories or inaccurate judgment of the experienced situations. After all, the findings will be valuable for the audience but the limitations must be underlined while reviewing the results and the discussions. 11 4) The Entrepreneurial immigration Theory of Science up to the point of mixed embeddedness, including analysis 4.1) Summary Interviews including General findings In the following section we have summarized the four interviews made. Farhad (refugee): grew up in an academic family, with his parents starting their own business. Because of the political background the family could not take governmental working positions. Farhad was motivated by being like his father, starting his own business. He could not go to university (politics). As Farhad arrived in Sweden he started within an ethnic network a pizza shop, a necessity for job, parallel with university studies. After some time an opportunity finally occurred within trade of hardware. The success lasted for about 8 years and then Farhad entered the retailing with trade of soft drinks. Behzad (refugee): came from a family with business background. He likes to make money and his entrepreneurial direction was partly motivated by the fact that he wanted to be his own self-employed. His first business background as self-employed came in Teheran where he co-partnered with a clothes manufacturer in order to find a living for his family. After immigration to Sweden, Behzad was forced to find a job again. He entered a fiberglass producer as work labor but got a lung disease so he had to quit. Then an opportunity came for him to start his taxi business. Eventually he grew his business despite the challenge after the deregulation of the taxi industry. Mojgan (planned immigration): was brought up with a self-employed father, developed an academic career within geology, a post graduate exam. After some successful years she was influenced by other colleagues in her network, to try the western life. Mojgan ended up in Lund, got an opportunity to start her own business founded partly by LUIS. She got her first customer 2012 and at time of the interview she was in a process of market her application idea throughout Sweden. Morteza (planned immigration): originally came from an academic family. Motivated to study and to see different parts of the world, he got his engineering school initially in the Philippines. During the war the embassy pushed the foreign students to return back to Iran. Morteza however, now with many western friends took the chance to enter into Sweden. He continued academic engineering master studies here. Parallel with studies he got a job for a Swedish construction firm which later got bankrupt. After some work within the municipality Morteza got an opportunity to enter the recycling business, at time not developed, in the early 90´s. The business expanded over the years, but it was challenging for him as part of the market was informal, leading to threat and other hazel within the community. General findings In the model below we have summarized the interpretations of the interviews by mapping each respondent’s respective market they entry and their progress. 12 Within both groups (refugees and other immigrants) we did not see any differences. However there were a tendencies witnessed that the less educated respondents initially ended up in the low growth, low threshold markets. Interestingly a common trace was found, in each case something unpredictable had occurred prior to the opportunity recognition, like an illness, being released from a job position, or denial of a job. 4.2) Vacancy chain opening (Market B) In our view examples of these markets in Sweden can be a local Pizza and Kebab restaurants, tobacco kiosk, a single driver taxi, a gardener, a tailor or a shoemaker. Our results identify the entry into Kloostermans (2010) vacancy chain window among several responding entrepreneurs. Farhad entered the first Swedish business more of necessity motivated to generate income for his family. Farhad express it in the following way: “I started the shop (pizza) with a friend and my brother. We were all Persians (homogeneous). It was hard as we did not have any experience in the beginning (low skill). We had many challenges (low profit), the guy who sold the place cheated on us (informal market)……… After one year we decided to contract out the pizza shop. It was good deal for us. We managed to get things done with a good price on a very bad economic condition. Eventually I sold the shop and moved on (sociability and adapting to changes-learning).” According to Kloosterman (2010) there are “mixed blessings” with the vacancy chain opening, which we can see from the response of Farhad. They entered the ethnic pizza market, all Persians, with minimal skills (low entry barrier), they had to trust their social network, which they did, but they got cheated. Kloostermans (2010) view here is that the vacancy chain on the one hand put pressure on the individual capital, for instance knowing how the market works but in addition there is a looked in effect by the ethnic market which in many cases creates an informal market due to the high competition with little or no growth. This leads to low profitability with low salaries not reaching the 13 minimum legislation of salaries. The social embeddedness in this case, meaning the need to trust others, in order to get a chance to act in the market is important. However in this case, Farhad learned fast by selling his business and moved on (Portes, 1994). The importance here is to learn to survive and to manage the right strategies in order to progress in this ethnic informal market. Kloosterman (2010) underline here the overlap of social capital with ethnic capital. Behzad, also refugee, got out of necessity also in through the vacancy chain window, after he was forced to quit his employment due to unhealthy lungs. His offer through his social network was a single taxi business, expressed here below: “…So not again no job for me for a while! For 6 months I had my pension to find a new job, but after 1 month, I got bored and I thought I have to find a work before this period is over. So my brother advised me to start with the taxi, as it was easy and the market was good as well.” Here we can see a replication of the ethnic market occurring within the vacancy chain window and the ability on the individual level to adapt to the market and use of the social network. But it was also the effect on political level (macro) opening for the opportunity to start taxi was easy. A taxi driver just needed to apply for a license and passing a test, including limited investment (Urban & Slavnic, 2008). The deregulation of the taxi market created many opportunities and some of them like in Behzad example eventually moved on to next level the Post-industrial, low skilled market, by growing his business. The necessity driven opening for Behzad in our view came from the expression where he got bored with his unemployed. We explain this by the fact that he had full responsibility to take care of his family, so for him starting the taxi was most likely a release, as income for the family was a must. In this first part of the study you can clearly see how those respondents enter their career here in Sweden in the vacancy chain openings, much due to their co-ethnic embeddedness. Our revised model has come into clear use because the original model with human capital as explanatory factor wouldn’t identify the opportunities from Behzad and Farhad here so easily. But by following the revised factors like entrepreneurial skills, which particularly can be seen in Farhads case and the motivation out of necessity due to that both respondents had to support their families, indicate that they had a longer vision and that they wanted more than just getting a job. They were both very open to changes, curious and made fast decisions, kept learning from their necessity driven opportunities, which gave them new chances. It is also notable here that the risk for the respondents of the “locked in effect” must therefore have been higher, even if for them it was not a conscious or even obvious risk. As our revised Kloosterman (2010) model also indicates the market entry of Behzad and Farhad were both in stagnating markets, with increased competition. This indicates that the necessity path took place due to their limited education and the embeddedness in the co ethnic market according to our view. 14 4.3) Post industry/low skilled (Market C) Behzad got the opportunity to grow his business, with or without knowing the effects at time of the deregulation of the taxi-market during 1990 (Urban & Slavnic, 2008): “All of the sudden there was an opportunity in Skurup. This company had several fixed trips in a day for handicap people and students and sick people. So it was not very much dependent on the market changes and the economic condition……. We came to know that we could participate in different auctions for different deals about fixed taxi rides for the government“ With this quote we can see, on the one hand that Behzad acted on the opportunity to buy a friend’s firm. He also stated that he learned to negotiate for fixed governmental fairs (improved skills-micro level). According to Kloosterman (2010) individual skills including improved learning, in this way, how the business works, is the way out and up towards a market growth, which we can see in Behzads case. In addition to reviewing the interviews on the macro level, many drivers previously in business (before deregulation) sold their firms. These decisions started because of the insecure deregulated market with variable costs, which stressed the older taxi firms, to sell off. The intension of the deregulation (macro level) was to generate a more efficient market with flexible competition for fair prices (Urban & Slavnic, 2008). Behzad expresses the taxi-firm purchase as an opportunity; we argue that this opportunity came up in addition to individual skills (micro level effects) also due to macro political decisions. But Urban and Slavnic (2008) underline that the quality only partly improved after the regulation and that pricing only slightly were reduced to specific groups, like for the public procurements (schools, hospitals). So Behzad, as an entrepreneur, had to fight in the same market with less money for the same mileage, as he grew his Taxi business. The fact that he managed to focus and generate public offerings (schools, hospitals =fixed rides) most likely saved his business growth. Behzad expressed it in the following way: “We came to know that we could participate in different auctions for different deals about fixed taxi rides for the government” Within the Kloosterman (2010) mixed embeddedness model, moving from one market (ethnic market) to the next level, the Post-industrial/ Low skilled market needs sociability and strategy as mentioned previously to maneuver towards the next level. Behzad according to our view was motivated to grow his business which in combination of his strategically decisions took him to the next level. However what we didn´t learn from Behzad was how well he adapted to the deregulation in the sense using his drivers for longer hours with the same payment. Did Behzad in a way succeed as entrepreneur on behalf of other drivers locked in within the ethnic community? In Kloostermans (2010) theory this would be part of the informal market, which we do believe was used here unintentional by Behzad. 15 One additional argument is that the employment system among taxi drivers changed from fixed to result driven salary (NUTEK, 1996). The effect of which is that the companies reduced income, transferred over to the individual drivers by reduced per hr. income compared to the same mileage. Also Farhad made a career from the vacancy chain opening to the post-industrial /low skilled, where his trade was in hardware goods but without internal innovation of his business, we kept him in this window. Farhad used his network within his family (micro effect) in a business segment at the time where the need of hardware, the market-growth, was growing fast (macro effects). One can also see in Farhad case that the education he got after the pizza-shop and the employment as engineer in a fairly big firm, most likely was to his advantage as he developed his own business throughout the Nordic Market. Morteza entered his business in the same window the post-industrial/low skilled with the recycling business. In his case, the municipality of Skurup sponsored him for a year to research on better ways of recycling wastes. With a functional model he got the opportunity to start his business. We argue that this case was supported on the one hand by his individual skills (micro level) and on the other hand, the problem for governments where citizens generate too much waste, and the awareness in general around recycling took off (macro effects). Morteza expresses his entry to the recycling business in the following way: “Most of the recycling factories gathered all the toxic substances and just burnet them all together and put them under the ground back then. Plus they never cared about re-usage of the building materials.” Morteza showed entrepreneurial skills clearly. He fetched an academic degree and also paid attention to that he did not enter the market within the vacancy store, most likely due to his academic background. It was not a surprise that he entered an expanding, novel market, even not high-tech, which is also in line with Kloosterman´s (2010) model. Kloosterman states that the model can be seen as striving from the bottom left to the top right position in the model. Education and individual skills are key factors here, in order to make a career towards the growing markets. In Morteza’s case we can also see that we got macro effects, as his entrepreneurial opportunity is related to the time where waste and recycling was initiated with a higher focus from politicians and society. Further the investment in this market seems not so high, so the threshold level was low, creating a recycling line of waste materials. 4.4) Post-industrial/High skilled Market (Market D) Mojgan entered the entrepreneurial career in the Post-industrial /High skilled market. After a long career she and some of her colleges migrated, all with high positions and academic professions on their CV. Mojgan expresses it like the following quote: “All the heads of the department that I employed are now out of Iran working in a high position in different countries, in GIS departments or even being entrepreneurs… Chosen to come here for a six- 16 month course……… I founded the company in July 2011 with another partner of mine who was a PHD student and LUIS back up. I got introduced to Ideon and started working here. Mojgans quotes expresses the need for, on the one hand high qualification in her case within the field of technology and also her experience and previous career as a high skilled manager Kloostermans (2010). She got tempted to peruse a career in western countries as she expressed, that so many of her friends left the home country for better wages and life style. Here, we see like in Schaeffer´s (2010) study that opposite refugee, other immigrants do have a much larger freedom to plan and choose their paths. In addition Mojgan did not enter any low entry barrier market and hereby avoided for instance the ethnic market in Kloostermans (2010) study. But also for Mojgan we can replicate that according to the Gem (2013) report, there is a movement from non OECD countries into the western innovative markets, leaving policymaker to ease up entry within special criteria of expertise. The individual effect of these macro level factors for entrepreneurs are for instance working or study permits (migrationsverket.se) But with Mojgans entry to Sweden, has changed in the transformation to the global market. Even if Mojgan in this study entered a high growth, high skilled market, it can be an effect of the overall global transformation into high technology and a global network of high skilled well educated people. The other respondents in the study entered Sweden much earlier where the markets have changed over time. 4.5) Motivation Starting a business with the need factor was common among respondents and in line with Kloostermans (2010) research too. Even if it in some cases was expressed as an opportunity, something had changed in their lives prior to entering their business field. “I needed to make money, we only had a student loan by then and I was married at the same time.” Farhad Behzad´s comment, prior to entry into the taxi business: “They found out that I had allergy to fiberglass and my lungs are damaged and I have to stop that work too.” Behzad Morteza´s comment before entering the recycling business. “Well after all, we all had to leave the company because of bankruptcy.” Morteza Even for Mojgan you could see that her first choice was to get employed within the science field, but she failed to reach an employment and instead got the opportunity to initiate a business idea through LUIS (Lund University Innovation System). 17 “But unfortunately, my qualification was so high that it was almost impossible for me to find a job… There was basically no organization that needed someone with a post doc degree to join them.” Mojgan And Mojgan further underlined family reasons, as part of her efforts in becoming an entrepreneur. This is partly different from the men, which also was found in Kirkwood´s study (2009). Common for all respondents are that they had use of their motivation in their entrepreneurial progress and particularly when something unexpected happened. They did not give up and even with necessity they kept on striving for something more in line with their entrepreneurial targets. In Kloostermans (2010) opportunity model you can identify the human capital, but it does not mean he particularly points towards the strong motivation and the entrepreneurial skills we identified in our interpretations. Strong motivation supported the respondents not only on the micro level but also, within their family and their personal development, but also in coping with macro level issues as well. Mojgan for instance, was striving with the university trying to understand its principals before she learned how to become an entrepreneur under the umbrella of the university. Behzad further was motivated to learn everything about the Taxi structure and its regulations, he never settled with “just being a driver”. 4.6) Culture and Background With exceptions of Mojgan all respondents mentioned language as a barrier in entering Sweden as entrepreneurs or workers. This may be an effect that we have an international language working throughout the world entering the high skilled high growth market. In Kloosterman´s (2010) opportunity model as well as in our revised version you can see that when most of our respondents entered Sweden they came in through the markets with low threshold level. So here, we can replicate from Kloostermans findings that lack of language or lack of education most likely leads to necessity driven work together with the social embeddedness (the strong culture). The wider social network within the Persian community was also mentioned, in several ways. The support came either from family, cousins or friend’s network, also replicated in recent studies (Foreman & Peng-Zhou, Jan2013). It was used mainly for contacts, financial support or for advice. Another observation we made, was the fact that all of the respondents had a business background from their families. Mojgan and Farhad expressed it in the following way: “So as a self-employed he (the father) had many people working for him. From my point of view it definitely affected me because I noticed that my father can provide us with everything.” Mojgan 18 “In Iran especially in my family because of my family’s political activity that they had, they couldn’t work for the government. They had to start their own business as by then most of the public sectors were owned by government.” Farhad Our interpretation here is that it may be easier to initiate and motivate a career of entrepreneurship, when brought up among family and friends who previously have been self-employed. 4.7 Entrepreneurial skills Among the respondents there were never any expressions for giving up, even with the experience of failure and threat, new directions were taken. “So, I was doing pretty good and continuing to expand, until the competitors started attacking my working environment at nights. They started to break things, rubbed the goods, burned my workspace and created lots of problems for me. But still I was continuing.” Morteza Sarasvathy et al. (2011, s70) underline the importance of handling failure in a proactive way for entrepreneurs. She expresses it in the following way which really makes entrepreneurs differ from other groups. “…failing a business does not mark you for life as a failed individual, and if you can overcome the grief of a failed business and learn from it, then you have a fair chance of doing better (smarter) the next round.” All Our respondents except Mojgan experienced failure, in their achievements forward and they learned from them. The ability, even out of necessity to develop a business was there, we identified this in several cases. The indirect macro level effects in Kloostermans model (2010) was replicated as a part of their growing business opportunities. The networking ability through family, friends and others were also common among the respondents. In other words they used their means while developing their business, which is also in line with Sarasvathy et al. (2011) model. Financing was never really a problem for this group, even if we could not judge how the financing was generated. It was always a way out for these respondents in their entrepreneurial efforts. 4.8) Refugees There was a slight overrepresentation in the category of vacancy chain openings of Kloosterman (2010) for the refugees, but it also involved lower education for these two respondents upon entry to Sweden. In addition to planned immigrants, refugees entered Sweden at a later stage, when the market conditions for entrepreneurs were also changed, which is one reason why we couldn´t use this tendency as explanatory factors for the refugees. 19 With these findings in addition to the fact that we could not see any other clear differences between the two groups, we argue for the fact that the human capital supported these entrepreneurs in their progress forward. In our version particularly motivation, the entrepreneurial skills and experience in addition to the ability to handle the environmental changes were the most solid stimulator of their success. 5) Discussion At an initial thought, one can think that traumatic experiences are combined with refugees entering a new country, which in a way limits those people to move forward. But it appears in this case that after healing and by depending on a strong human capital in addition to the entrepreneurial skills supported those entrepreneurs forward. Further the strong entrepreneurial motivation to move forward and to handle failure supported the respondents in finding new opportunities and transfer from employment to self-employed or entrepreneurship, in some cases very successfully. The research question: How does the establishment of entrepreneurial self-employment look like for refugees (according to the UN definition including quote refugees) compare to the other groups of Immigrants (according to SCBs definition)? Do refugees, remaining in Sweden, with entrepreneurial inclination, differ from other immigrants in their ability to identify entrepreneurial opportunities and if so in which ways? We met results well fit to the research question, but not with differences between the two main groups, as originally thought, but rather with similarities within the general entrepreneurial theories. These patterns were registered not only on the micro level but also on the macro level of Kloosterman’s (2010) model. In other words, we observed that immigrant entrepreneurs of our study, working with their means (supply) to define opportunities in the surrounding (demand), regardless of their immigration status. There was a slight overrepresentation of the respondents entering Sweden with low education, building their first business within the vacancy chain window. This vacancy chain store opening is the one market, which Kloosterman in one way, uses as a warning for creating a locked in effect. Kloosterman´s work relates opportunities, resources and outcomes of immigrant entrepreneurship in a systematic way (Kloosterman, 2010). But on one point relating to the vacancy store, our finding questions the so called locked in effect within the vacancy chain window. Within our study, we had respondents entering the vacancy chain store, but with their skills, network and entrepreneurial experience they all found a way out of this window, preventing them from the locked in effect. Our interpretation is that the entrepreneurial ability and skills along with the ability to identify opportunities and to act upon the changing environment, is the outcome that differs the entrepreneur from a self-employed non-entrepreneur businessman. We therefor argue that Kloosterman´s model has 20 not really fitted the general entrepreneurial theory within his work, meaning his measurement to identify paths for entrepreneurial firms vs. other self-employed businesses have been combined as one group of respondents. By applying further entrepreneurial definitions and models of entrepreneurial methods (Sarasvathy et al., 2011) Kloosterman´s model could be understood, when it comes to the locked in effects. In the future we therefor argue for developing a clear cut between general selfemployment and entrepreneurs when researching on immigrant entrepreneurs. As far as refugees are concerned, we think it´s reasonable to conclude that with the entrepreneurial skills, time will heal individuals even if they differ upon entry to their new country. These findings were altogether discussed among the authors, and should leave a valid qualitative study. The selection of respondents was also well fitted to the Kloosterman´s model which further increases the validity of the study. Finally we had to deal with changing markets over time as the respondents came into the Swedish market during different times, but with our conclusions we argue that those effects does not interfere with our findings. 21 Cited works Aldrich, H. (1975). Ecological Succession in Racially Changing Neighbourhoods: a Review of the Literature. Urban Affairs Quarterly, Vol 10 pp 327-348. Amit, R., & Mueller, E. (1995). "Puch" and "pull" entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Vol 12 pp 64-80. Bauder, H. (2008). Explaining Attitudes towards Self-employment among Immigrants:A Canadian Case Study. International Migration, Vol 46 Iss 2 pp 109-133. Block, J., & Wagner, M. (2010). Necessity and Opportunity Entrepreneurs in Germany:Characteristics and Earning s Differentials. SBR, Vol 62 April pp 154-174. Braunerhjelm, P., Holmquist, C., Nyström, K., Stuart-Hamilton, U., & Thulin, P. (2012). 2012Entrepreneörskap i Sverige. Örebro: Entreprenörskapsforum. Byers, T. H. (1997). Characteristics of the entrepreneur: Social creatures, not solo heroes. In I. R. Dorf, (ED.) The handbook of technology management. Boca: Raton CRC Press LLC. Davey, T. ,. (2011). Entrepreneurship perceptions and career intentions of international students. . Education & Training, Vol. 53, pp. 335-352. Deumert, A., Marginson, S., Nyland, C., Ramia, G., & Sawir, E. (2005). “Global mirgration and social protection rights: The social and economic security of cross-border students in Australia. Global Social Policy, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.329-352. Donald, L., & Landström, H. (1999). "The Climate for Entrepreneurship in European Countries in Transition". In J. Mugler, The Blackwell Handbook Of Entrepreneurship. Blackwell. Foreman, J., & Peng-Zhou, P. (Jan2013). The strength and persistence of entrepreneurial culture. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol 23 Iss 1 pp 163-187. GEM. (2013, 03 03). Gemconsortium. Retrieved 03 03, 2013, from gemconsortium.org: http://www.gemconsortium.org/ Glazer, N. (1955). Social Characteristics of American Jews. American Jewish Yearbook, Vol 55 pp 133149. Green, C., Kler, P., & Leeves, G. (2007). Immigrant overeducation: Evidence from recent arrivals to Australia. Economics of Education Review, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp.420-432. Husam, O. (2011). Arab American entrepreneurs in San Antonio, Texas: motivation for entry into selfemployment. Education, Business & Society, Vol 4 Iss 1 pp 33-42. Kirkwood, J. (2009). Motivational factors in a push-pull theory of Entrepreneurship. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 346-364. Kloosterman, R. (2010). Matching opportunities with resources; A framework for analysing (migrant) entrepreneurship from a mixed embeddedness perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol 22 no 1 pp 25-45. 22 Kloosterman, R., Leun, J. v., & Rath, J. (1999). Mixed Embeddedness: (In)forma Economic Activities and Immigrant Businessesin the Netherlands. International Journal of Urban and Regional Reserch, 23 (2), june, pp. 253-267 . Knight, F. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. . New York: Houghton Miffin. Langemar, P. (2010). Kvalitativ forskningsmetod i psykologi. Stockholm : Liber AB. McDougall, P. P., & Oviatt, M. B. (2000). International entrepreneurship:The intersection of two research paths. The Academy of Management Journal, Vol43, Iss 5, pp 902–906. migrationsverket. (2013, 05 17). migrationsverket. Retrieved 05 17, 2013, from migrationsverket: migrationsverket.se NUTEK. (1996). Avregleringen av taximarknaden. En analys av regionala effekter. Stockholm: NUTEK. Panayiotopoulos, P. L. (2006). Immigrant enterprise in Europe and the USA. London: Routledge. Portes, A. (1995). The sociology of immigration. essays of networks, ethnicity and entrepreneurship. New York: Rusell Sage Foundation. Poschke, M. (2013). Entrepreneurs out of necessity’:a snapshot. Applied Economics Letters, Vol 20 pp 658-663. Qasemnezhad Moghaddam, N. (2010). Evaluating the Islamic Azad University students entrepreneurship. Innovation and Creativity in Science, Vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-20. Razin, E. (2002). "Conclusion The economic context, embeddedness and immigrant entrepreneurs". International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour&Research, Vol. 8 Iss:1/2, pp.162-167 . Reynolds, P. S., Michael Camp, William D. Bygrave, Erkko Autio, & Hay, M. (2001). GEM 2001 Executuve report. London UK: Babson Park. Riddle, L. (2008). Exploring their development potential. ESR Review, Vol 10 Iss 2 pp 28-36. Sarasvathy, S., Read, S., Dew, N., Wiltbank, R., & Ohlsson, A.-V. (2011). Effectual Entrepreneurship. New York, NY: Routledge. Schaeffer, P. (2010). Refugees: On the Economics of Political Migration. International migration, Vol 48, Iss 1, pp 1-23. Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. Trans. R. Opie from the 2ndGerman ed. [1926]. Camebridge, MA,: Harvard university Press. UN. (2013, 03 04). Audiovisual Library of International Law. Retrieved 03 04, 2013, from untreaty.un.org: http://untreaty.un.org/cod/avl/ha/prsr/prsr.html Urban, S., & Slavnic, Z. (2008). Rekommodifieringen av taxibranschen-förändring av ekonomiska förhållanden och etnisk sammansättning. Dansk sociologi, Vol 1 No 19 pp 75-94. 23 Waldinger, R. (1996). Still the promised city?; African-Americans and new immigrants in postindustrial New York. Cambridge, MA:: Harvard University Press. wikipedia. (2013, 04 11). wikipedia. Retrieved 04 11, 2013, from wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persian_people Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research- Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 24