Saving the Pine Barrens

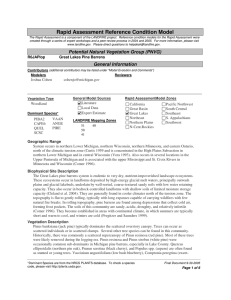

advertisement

What We Need to Know for Their Conservation 1. We can’t control their past, but we can control their present and future. 2. It’s mostly about us, but not all. 3. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. 1. We can’t control their past, but we can control their present and future. When we refer to “the” pine barrens, we mean the Atlantic coastal pine barrens 8975 square kilometers in New Jersey, on Long Island and Cape Cod The Laurentide Ice Sheet is the story 400 feet lower sea level Retreat 11,000 years ago created the pine barrens Pine barrens are plant communities that occur on dry, acidic, infertile soils dominated by grasses, forbs, low shrubs, and small to medium sized pines. The most extensive barrens occur in large areas of sandy glacial deposits, including outwash plains, lakebeds, and outwash terraces along rivers. A thin ubiquitous layer of windblown sand and silt caps the glacial deposits. Deposited when there was little or no vegetation, generally a few feet thick Mixed with deeper layers by frost action Glacial deposits are 200-600 feet thick Bedrock is under that Most Cape Cod soil is 85% sand, 15 % mixed Plants growing here have to be prepared to deal with high acidity Must be able to deal with fire, which both happened naturally and eventually by man Must be able to live in low-nutrient conditions Predominantly Pitch Pines and Scrub Oaks There were, of course, fires sparked by lightning, but most of the fires were started by the native people who populated the area. Sometimes the goal was simply to create fields for planting; other times it was to open up the forest so that berries and other sunloving plants would thrive. The plants provided food but they also improved the hunting by attracting deer and other animals. By 1913 experts estimated that Massachusetts had 1,000,000 acres of "waste land" — land that was not only unprofitable and unsightly but a serious fire hazard. With an almost endless supply of dry vegetation, wildfires could burn out of control for days. A century ago, the Massachusetts legislature created the office of State Forester. His job included the prevention and control of forest fires. The mainland of southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, and the Elizabeth Islands are especially prone to fires. Among the only trees that thrive in this region's sandy soil are pitch pine and scrub oak; both species are susceptible to fire but pitch pine's resin-rich needles are especially so. With the added fuel from ground covered with dried pinecones, needles, leaves, and twigs, these forests can produce some of the fastest-moving fires in the country. Fires have swept through Myles Standish State Forest (MSSF) many times since the state first purchased the land in Plymouth and Carver in 1916. Naturalists have analyzed pollen cores from ponds in the forest and found layers of charcoal between layers of sediment, scientific proof of what common sense and Indian lore tell us — fires have been part of the natural cycle here for millennia. Only since English settlement of the area have forest fires been seen as a threat to be contained. In the twentieth century, more and more resources were directed at fire prevention. State and federal officials launched education programs featuring Smokey Bear and began publicizing a classification system for fire danger. A network of access roads was created through woodlands, fire towers were built at key vantage points to help with early detection, and firefighting equipment improved rapidly. But conflagrations still occurred. Seven years before the 1964 fire, an even more destructive blaze started on the Carver side of the forest. It raged out of control for two days. Like any huge wildfire, flames arched across roads, and embers blew across ponds. Sixty-four communities sent 2,500 men to battle the blaze. But nothing could stop the 40- to 50-foot-high wall of flame that consumed 15,000 acres on its way to the Atlantic Ocean. In recent decades, there has been intense residential development surrounding state forests and parks. Dozens of structures were lost in the 1957 and 1964 fires. Today, even a medium-size wildfire in southeastern Massachusetts would likely destroy hundreds of homes and possibly result in loss of life. Fire departments are better trained and respond more quickly. Cell phones allow members of the public to become fire spotters. In the 1980s and 90s, no large fires escaped suppression at Myles Standish. As a result, in the past quarter century a mature forest has grown up in some parts of MSSF. Taller trees help reduce the flammable understory and with it the fuel fire needs to spread, but there are still large areas full of extremely hazardous fuel. Wildfires continue to pose a serious risk to the public, and land managers have added what they call "prescribed burns" to their firefighting tools. They began in 1998 with a small test at Myles Standish. The experiment was successful, and after some initial controversy, controlled fires are now widely used in the region. ? Will we keep in mind the knowledge we gained in 1957 and 1964? How soon before we forget? Is there an even better way? How do different animals react to fire? Whereas Columbine Duskywing often occurs in alkaline habitats, and uses only Aquilegia canadensis as a larval host plant, the eastern subspecies of Persius Duskywing is confined to dry pine-oak areas, often acidic, and uses only Wild Indigo, Baptisia tinctoria, in our area, although it is also found on Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis) in the midwest. Baptisia tinctoria (common names include yellow false indigo, wild indigo and horseflyweed) is a herbaceous perennial plant native to eastern North America. It prefers dry meadow and open woodland environments On Martha's Vineyard, the species is a tumbleweed: it grows in a globular form, breaks off at the root in the autumn, and tumbles about. Feed on pitch pines Fire suppression would therefore lead to the growth of deciduous trees that would outcompete the pitch pines, adversely affecting the future of the Zanclognatha Only currently appears in 8 Massachusetts communities, including Plymouth Amphibians generally survive fires – as far as we know Mammals are mostly big enough to move away fast enough Some reptiles don’t know any better, like black racers; can take 25 years to recover Some birds may never return, particularly ground nesters Can we figure out the optimum time for burning? It’s mostly about us, but not all. 2. 1. Humans ◦ We live here We leave year-round in the region We live in summertime in our cottages ◦ We play here We fish We hunt We bike, we walk, we hike, we bird, we camp ◦ We work here We don’t extract much these days We’ve been here a long, long time, and we’re not going away any time soon. Mastodon, mammoth, and other extinct animals of the Pleistocene Epoch, and most, if not all, of the animals and plants that now live in northeastern North America, survived the Laurentide glaciation on the exposed continental shelf. Evidence for the presence of mastodon and mammoth is provided by the numerous teeth dredged from the sea floor of the continental shelf and the Gulf of Maine. ”Trusting to their excellent camouflage, Eastern Whip-poor-wills typically roost in the woods by day, only to emerge at night to hunt for flying bugs over scrubby forest openings. Loss of these open earlysuccessional areas has likely been a contributing factor to the decline of Eastern Whip-poor-wills in Massachusetts.” Northern red-bellied cooters today live in just one county in Massachusetts, but archaeological data indicate that northern red-bellied cooters likely lived farther to the north, south and west in pre-colonial times. Additionally, data from prehistoric Indian middens in New England suggest that humans used cooters for food, perhaps causing local extinctions. There are approximately 300 breeding age individuals known to exist in this population. While headstarting is an important part of the recovery strategy for northern red-bellied cooter, the strategy’s emphasis is on habitat protection. Changes in land use have caused loss of nesting and basking sites. In the past, fires frequently burned the pine barren habitat occupied by this turtle, leaving openings in the mixed pine and oak forest. For 100 years, the area has been protected from fire; allowing most of the remaining undeveloped areas to grow into closed-canopy pine forest. 3. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We can try a three-pronged approach: Research Education Advocacy Together, they should lead to Action. What do we have going on so far? Do we know, beyond incidental sightings, what we have living in the pine barrens? ◦ We can work with proven protocol and web-based data entry programs ◦ We can partner with outside organizations ◦ We can design our own projects ◦ We can challenge others to design projects Can we empower students of all ages to become involved in data gathering? State level projects like the Breeding Bird Atlas 2 are a big help Localized projects like those of the Pine Barrens Community Initiative are even better Native plants program Strong Friends of Myles Standish State Forest and Southeastern Massachusetts Pine Barrens Association Research leads to education; once armed with data, we – and this means all of us - can better tell the story of the Pine Barrens. We can design and exhibit appropriate interpretive signage, produce brochures and websites. We can give lectures. Education leads to advocacy. Once we know what we have and what it needs, we can push for its protection, which sometimes comes in the form of funding from governmental sources for staffing, etc. …has to be a team effort. Remember: ◦ The Pine Barrens have a past, present and future, and they all involve us. ◦ The Pine Barrens are here for all of us, human, plant and animal. ◦ The Pine Barrens can be saved through research, education and advocacy.