Argentina and Chile

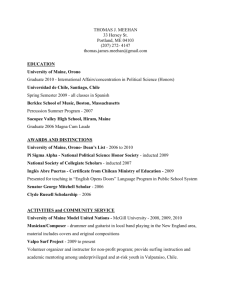

advertisement

Argentina and Chile •History •Argentina •Chile •Prestige Conquest and Colonisation: Settlement of Argentina and Chile • Spanish presence in Argentina from 1516: origins of settlers to each region begins to shape dialects • Spanish arrival in Chile 1540 • Settlement of Chile difficult natural geography and conflict with natives. Not complete until late 17th Century, centralised population. Colonial Period • Argentina – Constant reshuffling of settlements and jurisdiction – Southern Pampas settled from Buenos Aires – Steady growth of Buenos Aires as a commercial hub from late 18th century • Chile – Originally formed part of the Viceroyalty of Lima as its ‘founders’ had ventured south from Peru – Frontier garrison against Mapuche and European enemies: Vast standing army aided linguistic homogenisation Independence & Mass immigration • • • Independence from Spain during early 19th century Argentina – Mass immigration from Europe throughout 19th and early 20th centuries leading to development of dialects. – Most significantly Italian but also Spanish, Russian, Syrian, Lebanese, French, English → Lunfardo and Rioplatense – Flourishing economy and population – Mixing of nationalities transformed language, especially lexicon – Strong influence of French romanticism on Argentinan oral and written discourse gave way to many lexical borrowings Chile: – Late 19th century expansion into Peru and Bolivia following the War of the Pacific – Similar waves of European immigration but with no such significant impact on language due to less concentrated population and no one major immigration group – More recent immigration mostly from other Latin American countries, adding to homogenisation of dialects. – More linguistic mixing with native languages than in Argentina Bibliography • Alvar, Manuel, Manual de dialectología hispánica: El español de América Barcelona: Editorial Ariel 1996 • Lewis, Daniel K., The History of Argentina USA: Palgrave Macmillan 2003 • Lipski, John, Latin American Spanish, London: Longman 1994 • Rojas Mayer, Elena M., El diálogo en el español de América: Estudio pragmalingüística-histórico Madrid: Iberoamericana 1998 • Confederación de Entidades Argentino Árabes: http://www.fearab.org.ar/inmigracion_sirio_libanesa_ en_argentina.php ARGENTINIAN or RIOPLATENSE Phonetic, Intonation, Conjugation and Lexicon Peculiarities • Rioplatense Spanish is mainly based in the cities bordering El Río de la Plata, thus Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, la Plata and Rosario in Argentina, but also Montevideo in Uruguay and the respective suburbs of these cities. • Classified as a dialect of Spanish. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8VzCH68yD Q&feature=related http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MaTjCil8SxU& feature=related • Spanish is the official language in Argentina, spoken by almost the entire population (+40 million) • Another 25 vernacular languages, both alive and extinct exist in various regions. The most important, spoken by over 1 million people & product of the internal migrations in Perú, Bolivia and Paraguay are: • Guaraní (spoken in the provinces of Corrientes, Misiones, Chaco, Formosa, Entre Ríos); made up of 6 dialects • Quichua, of the Quechua family; made up of 2 dialects: Quechua sudboliviano & Quichua santiagueño • Aimara (spoken in Jujuy, Northern Salta and by Peruvian and Bolivian immigrants) PHONETIC PECULIARITIES: 1- Main shibboleth in Argentine Spanish: the yeísmo, where the sounds represented by ll (the palatal lateral /ʎ/) and y (historically the palatal approximant /j/) have fused into one. This merged phoneme is generally pronounced as a postalveolar fricative, either voiced [ʒ] in the central and western parts of the dialect region (this phenomenon is called zheísmo) or voiceless [ʃ] in porteño, which is the Spanish spoken in and around Buenos Aires (called sheísmo). The pronunciation of y, ll is always an obstruent consonant, very different from a glide [i]. Lleno [ʒéno] ; yerba (mate leaves) [ʒérβa] = postalveolar fricative whilst hielo [ʝélo]; hierba (grass) [ʝérβa]= glide • Words like se calló and se cayó become homophonous • Pronunciations such as [ʒélo] for hielo are frowned upon in Standard Argentinian as a sign of low cultural level • This occurs especially amongst the porteños, the name given to the inhabitants of Buenos Aires. As you go further north or south of the Capital, this phonetic feature becomes less evident 2- Aspiration of the fricative ‘s’ when when followed by another consonant, E.g. viste (vihte), fuiste (fuihte), es que (eh que) Esto es lo mismo is pronounced something like [ˈɛh.to ˈɛh lɔ ˈmih.mɔ] • Pronunciation of the ‘s’ when at the end of a word. E.g. Vos, muchos, casas Clear differentiation between singulars and plurals 3- In some areas, speakers tend to drop the final r sound in verb infinitives. This elision is considered a feature of uneducated speakers in some places, but it is widespread in others, at least in rapid speech INTONATION: • Particular intonation pattern: The ‘Long Fall’ = a high tone on the most prominent syllable of a phrase and a fall to a low tone within that same syllable, which creates its melodic sound CHARACTERISTICS of the long fall: (typical but not obligatory) 1) falling pitch on a single nuclear syllable (navegar, concurso, publicados) 2) substantial lengthening of the nuclear syllable (lindo, medio, ríos) • The salient syllable is often greatly exaggerated in duration, sometimes lasting 5 times the length of the other syllables in a word • Spanish stressed syllables are usually not more than 50% longer than unstressed ones Where does this intonation contour come from? • There is at least one romance language known as robustly non-syllable-timed, which instead has a very noticeable lengthening of stressed syllables, either by lengthening the stressed vowel* , or lengthening the consonant closing the syllable*’ : Italian * fantastica ; *’ bello, fratello, impercepibile, terribile (down South) • Argentinian in many aspects follows intonation patterns of the Italian dialects and the porteños speak with an intonation that most closely resembles Neapolitan -Prestigious variety of Argentinian Spanish - Prior to the wave of Italian immigration, the porteño accent was more similar to that of Spain, particularly Andalucía PRONOUNS AND VERB CONJUGATION: • Voseo (absence of ‘tu’, replaced by ‘vos’) • Absence of ‘vosotros’, replaced by ‘ustedes’ & respective declinations • Modified form of imperative (eg. Vos, hablá más despacio; ¡andáte! ; ¡mirá! ; ¡escucháme! ; vení acá) • In the preterite, an s is often added, for instance (vos) perdistes. This corresponds to the classical vos conjugation found in literature. Compare Iberian Spanish form vosotros perdisteis. (This form is often deemed incorrect) LEXICON: About 9000 Rioplatense words, which in many cases are not used or understood anywhere else. Most differences concern fruits, garments and everyday objects, which have an immense influence from Italian. For example: fresas -> frutillas piña -> ananá (ananas in Italian) melocotón -> durazno maleta -> valija (valigia in Italian) (For a complete list: http://www.latimer.com.ar/miscelaneas/dicc-palab_arg.htm) EL LUNFARDO • ‘Puede considerarse como el idioma del tango argentino’. • It was born together with tango in the brothels at the end of the 19th century. • Some say ‘lunfardo’ was the word used by theives to classify themselves. The ‘fardo’ was what they called the big sheet that robbers wrapped their goods in. • Others say it comes from the French lumbard which referred to those who came from the Italian region of Lombardy. • Many of the words in its vocabulary come from Italian, especially from the Genovese dialect. Others are formed by inverting the order of letters (loca=colifa; pantalón = lompa) Bacán/ barulio = noise (baccano in Italian) Quilombo = a mess Laburo = job (lavoro in Italian) Birome = pen (biro in Italian) Tener fiaca = to feel tired, without energy (in Italian ‘sentirsi fiacco’) Mina = chica Pibe = chico Che = tío, colega Re = muy Recanchero/ bárbaro = cool Boludo = tonto, colega Es un embole = es muy aburrido BIBLIOGRAPHY: • Orlando Alba, Zonificación dialectal del español en América, in César Hernández Alonso (ed.), Historia Presente del español de América, (1992, Pabecal: Junta de Castilla y León) • Manuel Alvar, Manual de la dialectología hispana: el español de América (1966, Barcelona) • José Ignacio Hualde , The sounds of Spanish • Ellen M. Kaisse, The Long Fall, An intonational melody of Argentinian Spanish, , extracted from Current Issues in Linguistic Theory: Features and Interfaces in Romance, edited by Julia Herschelsohn, Enrique Mallén, Karen Zagona • Christoph Gabriel, Ingo Feldhausen, Andrea Peškova, Contrastive and neutral focus in porteño Spanish, University of Hamburg, IRom Collaborative Research Center 538 “Multilingualism”, Project H9. Chile • There is little variation in high level Chilean across the 2000 mile territory • However, there is more variation in the vernacular. • The dialect of prestige is that of the SantiagoValparaíso area. • Greater influence of indigenous languages than in Argentina Differences around Chile: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6O65 Gj7Rrs&feature=related Other Languages • 17 million Chileans, 14 million speak Chilean Spanish as their first language. • Chile is characterised by 9 other living languages – principally Mapudungun and Quechua – and 7 extinct ones. Phonological Differences • Lenz believed differences in Chilean Spanish could be attributed to the influence of the Mapuches – not been proved. • The relative homogeneity of Chilean Spanish is attributed to nature of Spanish of colonisers – generally rustic. • Most of the differences found in Chilean Spanish are present in other Spanish American dialects • Chilean differentiation is due to different social, political and administrative life in the colonial era. Main Phonological Features • Syllable and word final /s/ is reduced to an aspiration [h] or lost • Along border with Bolivia, there is some retention of sibilant [s] is found among Aymara speakers • In Cautín, /s/ is systematically lost due to interference of Mapundungun • Word final /n/ is alveolar - bien. Velarization is found only in extreme northern Chile – old Peru • Neutralizing syllable-final liquids happens in lowest classes - /l/ and /r/ • Urban working classes occasionally drop the word-final /r/, particularly in verbal infinitives Main Phonological Features • Most of Chile has neutralized /λ/ and /y/ in favour of a palatal fricative [y] – calle, cayó • Some lleísmo in rural areas of southern Chile • Some Aymara speakers of extreme north-eastern Chile do retain /λ/, but they are properly regarded as speakers of a macro-Bolivian dialect of Spanish • Cautín - /l/ features in Spanish words, probably due to the existence of a similar sound in Mapundugun. Main Phonological Features • The posterior fricative /x/ acquires a palatal pronunciation [ç] before front vowels (e and i), at times approaching a diphthongized [çj] – mujer • /x/ is weak aspiration in extreme southern Chile • Suppression of d in –ado • Chilean /č/ is routinely cited as a distinguishing feature of the dialect, in view of its frequent prepalatal articulation, approximating [ts]. There is a fricative pronunciation of /č/ in southern Chile. • In much of Chile, the multiple /rr/ is given a groove fricative articulation/assibilation - perro Morphological Differences • Unique use of vos • both vos and tú exist, but tú predominates. • Vos carried social stigma, however it is currently being regained by younger generations. • Hybrid forms have evolved: tus and yos due to hypercorrection and mixing tuteo and voseo, and cross-combinations e.g. tú tenís and vos tienes Morphological Differences • Flexibility of verb morphology used with both vos and tú • Endings are –ar = -ái - cantái • -er + -ir = ís – sabís/venís • Cautín – tú is the only form of address • There is also a predominance of the futuro atlántico: ir a Lexical Differences • Anglicisms due to the influence of the British in the mining industry • The extreme geography and isolation of many areas has caused considerable regionalization of daily vocabulary Lexical Differences • • • • • Arrechunches – personal possessions Chiches – money Gallo – guy Fome – boring Futre – well-dressed individual/member of the élite • Acaso = vale Influences from other languages • The main influence of indigenous languages is in the lexicon. • Influence of Peru on northern Chile • North-eastern Chile and Bolivia – blending of speech, especially among Aymara speakers - small but stable Aymara-speaking community. • Mapuches were the principal indigenous group of Chile – central region, successfully resisted the Spanish colonisers for many years. Driven further south by Spanish. • Initially an Incan presence in Northern Chile, but not very strong. • Extreme Western areas of Argentina share Chilean characteristics – Mendoza, San Juan etc – due to these formerly forming part of Chile. Influences from other languages • Still unsure about the extent of the influence of Mapuche/Araucano on Chilean Spanish • Mapuche still spoken in communities in Southern Chile, sometimes predominates over Spanish, but the language is receding. • Other small indigenous groups that had been present in Chile have ceased to exist. • Not a very strong African presence, but some black slaves were imported throughout the colonial period. Unsure about the extent of African influence on Chilean Spanish. • Easter Island and Chiloé Island are also characterised by differences. Influences from other languages • • • • • • • Quechua-influenced lexicon: guaso: rústico, campesino de Chile chuchoca: maíz cocido y seco huachalomo: lonja de carne chacra: granja garúa: llovizna pampa: cualquiera llanura que no tiene vegetación arbórea Influences from other languages • Mapuche-influenced lexicon: • cahuín: reunión de gente para beber y embriagarse; comentario, boche • guata: panza, barriga • un pichintún: un poco, una pequeña porción Bibliography • Alvar, M., Manual de dialectología hispánica: El español de América, (Barcelona: Editorial Ariel, 1996) • Lipski, J., Latin American Spanish, (London: Longman, 1994) • Moreno de Alba, J. G., El español de América, (México : Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1988) • http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero17/m apuche.html • http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.as p?name=CL Prestige Argentina Chile Argentina • Carlos Solé, 1991. (what prestige and status the Argentine variety of Spanish had) • 1) Rate their forms of Spanish against other forms • 2) language in terms of their own identity • 59% - consider the Argentine dialect to be ‘mal español’ • 48% believe that Spanish is spoken better outside of Argentina Value given to the speech variety of Buenos Aires as opposed to other varieties of Spanish • Although the status of the language is not perceived to be too high compared with that of Peninsula Spanish Solé’s study shows that the Argentine variety of Spanish is very important in expressing their identity • 83% of the population consider it to be a marker of national identity. Dialects • B.A. grew to be the second largest city in the western hemisphere and the social and cultural focal point for much of South America. • Rural dialects “have a greater tendency to represent poorer, less educated and less mobile populations.” (Mar-Molinero pp.53) Chile The use of voseo • Stigmatized in the late C19th after it fell out of use in Spain • Nowadays although overt (pronominal) voseo is stigmatized some studies show an increasing acceptance of verbal voseo. • Authentic/overt Voseo was not completely eradicated – class dependant Torrejón • Voseo was “becoming more accepted by younger speakers while becoming less of a target of stigmatization by older speakers of the upper class” • 3 reasons 1)Dissolution of hierarchy 2)Young desire to break from linguistic pattern of their parents 3)Increacing importance of schools/universities to spread the form. Torrejón looks at Brown and Gilmans (1960) criteria of solidarity and equality and states that the forms of address are becoming “more simplified and egalitarian”. Bishop and Michnowicz results • Usted used by and large to pan-Hispanic norms (i.e. power differentials) • But – informal pronouns generally used more frequently • Tuteo reported more than verbal voseo • General avoidance of voseo with strangers and foreigners • V-Shaped distribution of voseo across age and social class groups • Cross tabulation of age and social status show the adoption of voseo by the professional class to be a recent phenomenon B+M’s data confirms Torrejón’s informal observations • Verbal voseo most prevalent among the young • Sharp divide between older speakers • However, a possible stigmatization of verbal voseo could lead to less reported frequency on the linguistic survey • “Although verbal voseo remains a stigmatized form in Chile, it is less stigmatized among men, young speakers and working class and professional class speakers” (B+M pp.426) Labov 1966 – ‘Covert Prestige’ • “Use of a stigmatized nonstandard variety by a specific group to indicate solidarity or identification with that group” • - negative image of the use of verbal voseo but it is preserved as part of the Chilean linguistic trait – way to signal group identity. Bibliography • Bishop. K & Michnowicz. J, Forms of Address in Chilean Spanish, Hispania Vol.93, Number 3, September 2010, pp.413-429. John Hopkins University Press. • Mar-Molinero. C, The Spanish Speaking World: a practical introduction to Sociolinguistics. (containing information on Carlos Solé’s study) • Lipski, Latin American Spanish