23-24 Dubious Reasons for Mergers When Mergers Don't Make Sense

advertisement

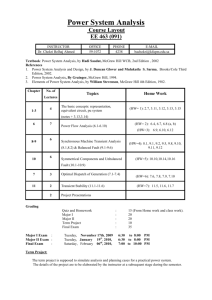

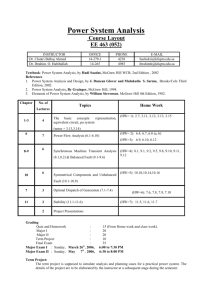

23-1 Fundamentals of Corporate Finance Second Canadian Edition prepared by: Carol Edwards BA, MBA, CFA Instructor, Finance British Columbia Institute of Technology copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-2 Chapter 23 Mergers, Acquisitions and Corporate Control Chapter Outline The Market for Corporate Control Sensible Motives for Mergers Dubious Reasons for Mergers Evaluating Mergers Merger Tactics Leverage Buyouts Mergers and the Economy copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-3 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) When one company buys another, it is making an investment. Thus, the basic principles of capital investment decisions apply: The buyer should go ahead with the purchase if it makes a net contribution to shareholders’ wealth. But, why would one company wish to acquire another? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-4 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Although shareholders may own the company, in most large corporations there is a separation of ownership and management. Thus, individual shareholders generally have very little say in the operation of the firm. Directors and managers can take actions which are contrary to the shareholders’ interests. One of the forces which keep them in line is that others, recognizing that the value of the firm could be enhanced, will try to replace the Directors and/or management. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-5 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) There are four ways to change the management of a firm: A proxy contest. The purchase of the firm by another firm in a merger or acquisition. A leveraged buyout of the firm. A divestiture of the firm. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-6 The Market for Corporate Control • Proxy Battles When a group of investors believes that the Board and its management team should be replaced, they can launch a proxy contest or a proxy fight. In a proxy contest, outsiders compete with management for shareholders’ votes. If the outsiders obtain enough proxies to elect their own slate of Directors, once the new Board is in place, it can replace the management. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-7 The Market for Corporate Control • Proxy Battles Most proxy contests fail. Such fights can cost millions of dollars. Dissidents who engage in such battles must use their own money. Management can use the corporation’s funds, and its lines of communication with the shareholders, to defend itself. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-8 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers and Acquisitions Proxy contests are rare – poorly performing managers face a far greater risk from mergers and acquisitions. There are three ways for a firm to acquire another firm: 1. Merge with it. 2. Purchase a majority of the shares. 3. Purchase some or all of the assets. The first option is referred to as a merger; the other two options are referred to as acquisitions. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-9 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers In a merger (sometimes called a statutory acquisition), the acquiring company combines all of the assets and liabilities of the target company into one. The and Acquisitions target company ceases to exist. In the second alternative, the acquiring company attempts to buy the target firm’s stock. The target may continue to exist, but it is now owned by the acquirer. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-10 The Market for Corporate Control • Mergers and Acquisitions In the second option, payment for ownership of the target company goes into the hands of the target company’s shareholders. In the third option, one firm acquires another by buying the target firm’s assets. Payment goes into the hands of the target firm. Sometimes the target sells only some of its assets. If the target sells all its assets, then it continues to exist as an independent entity, but only as an empty shell. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-11 The Market for Corporate Control • Leveraged Buyouts (LBO) Sometimes a group of investors will takeover a firm using an LBO. An LBO involves the acquisition of a firm by a private group using substantial borrowed funds. The LBO group then takes the firm private so its shares no longer trade in the securities markets. If the investor group is led by the management of the firm, then the takeover is called a management buyout (MBO). copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-12 The Market for Corporate Control • Divestitures Instead of selling a business to another firm, a company may spin-off the business by separating it from the parent. This is done by distributing stock in the newly independent company to the shareholders of the parent company. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-13 Sensible Motives for Mergers • Types of Mergers Mergers are often categorized as: Horizontal When the merger takes place between firms in the same business, e.g., Air Canada’s acquisition of Canadian Airlines. Vertical When the merger involves acquiring a supplier or customer, e.g., Pepsi owns Burger King. Conglomerate When the merger involves companies in unrelated businesses, e.g., a manufacturer acquires a bank. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-14 Sensible Motives for Mergers • When Mergers Make Sense A merger makes sense only if it adds value. Value may be added by better management, or by synergies, and other changes, which make the two firms worth more together than they were apart: FIRM A FIRM B > FIRM A + FIRM B copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-15 Sensible Motives for Mergers • When Mergers Make Sense Sources of synergy: Increased revenues for the combined companies, perhaps because of increased prices or a larger market. Economies of scale, i.e., the opportunity to reduce per unit costs by spreading fixed costs over a larger number of units. Economies of vertical integration, i.e., improvements in co-ordination and control of production. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-16 Sensible Motives for Mergers • When Mergers Make Sense Sources of synergy: Combining complementary resources, i.e., one of the firms provides the missing ingredient necessary to the other’s success. Merging to reduce taxes, i.e., if it is possible to reduce the total taxes of the combined companies, say because one has tax shields it is unable to use. Using surplus funds, i.e., if one of the firms has a shortage of good investment opportunities, and is unwilling to buy its own shares, it may instead purchase someone else’s. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-17 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense Diversification Diversification reduces risk, which is beneficial. However, diversification is easier and cheaper for shareholders to accomplish than it is for companies to do by combining their operations. Shareholders just have to buy shares of company A and company B to diversify their portfolio. Thus, they will not pay a premium for managers to combine company A and company B merely for the sake of diversification. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-18 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game During the 1960’s, some conglomerate companies made acquisitions which offered no evident economic gains. Yet, the conglomerates were able to produce several years of rising earnings per share (and, of course, rising share prices). Let’s see how this could happen. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-19 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game Table 23.2 on page 691 of your text shows the financial situation for two firms: World Enterprises (WE) is a rapid growth firm, with a high stock price and P/E ratio. WE has 100,000 shares outstanding and eps of $2.00. Muck and Slurry (M&S) is slow growth firm, with a low stock price and P/E ratio. M&S also has 100,000 shares outstanding and eps of $2.00. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-20 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game What would happen to eps if WE were to merge with M&S? If you look at column 3 of Table 23.3, you will see that: The total market value of the two companies is unchanged by the merger. The total earnings of the two companies is unchanged by the merger. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-21 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game Thus, the acquisition of M&S by WE provides no economic gains. But, if you look at column 3 of Table 23.2, you will see that the eps of the combined company has increased from $2.00 to $2.67. Can you see why the post-merger eps grew by 33%? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-22 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game Before the merger, WE’s shares were selling for $40, while M&S’s shares were selling for $20. Thus, WE gave-up only 1 of its shares to acquire 2 of M&S’s shares. If you you look at lines 4 and 5 of Table 23.2 you will see that the number of shares increased by only 50%, but earnings increased by 100%. Thus, eps must grow – not for economic reasons, but as a function of the math! copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-23 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game If you look at Line 7 of Table 23.2, you will see that before the merger: WE shareholders bought high growth and $0.05 of immediate earnings for each $1 invested. M&S shareholders bought low growth, but $0.10 of immediate earnings for each $1 they invested. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-24 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game If you look at Line 7 of Table 23.2, you will see that after the merger: WE shareholders get lower growth and $0.067 of immediate earnings for each $1 invested. M&S shareholders get higher growth, and $0.067 of immediate earnings for each $1 they invested. Thus, neither side gains or loses, provided that everyone understands the deal. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-25 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game However, financial manipulators try to cheat investors by making sure the the market does not understand the deal. If investors mistake the 33% increase for sustainable growth, then the P/E ratio will jump. The result: the price of the merged company will rise and the shareholders of both companies get something for nothing. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-26 Dubious Reasons for Mergers • When Mergers Don’t Make Sense The Bootstrap Game Lesson: Buying a firm with a lower P/E ratio can increase eps. But the increase in eps should not result in a higher share price. The short-term, immediate increase in earnings should be offset by lower future earnings growth. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-27 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions If you are evaluating a merger, there are two questions you should think about: Is there an overall economic gain to the merger? In other words, are the two firms worth more together than apart? Do the terms of the merger make my company and shareholders better off? There is no sense in merging if the costs are too high. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-28 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions Let’s look at a sample merger, which could be financed either by cash or by shares, to see if we can understand these concepts. Look at Table 23.3 on page 692. It shows the financial data for Cislunar and Targetco. Cislunar is considering merging with Targetco. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-29 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions Note the following in Table 23.3: The earnings of Cislunar and Targetco are $32 m and $4 m respectively. Combining the companies increases their earnings by $4 m due to increased revenues and savings on operating costs. This is the gain from the merger. Cislunar’s share price is $48. Targetco shares sell at 1/3 the price: $16 each. The market value of Targetco is $40 m. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-30 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions The total economic gain to this merger is $4m of extra earnings per year. Assume the earnings are a perpetuity and the cost of capital is 20%: Total Economic Gain = $4 m/ 0.20 = $20 m Thus, you can say, “Yes, there is an overall economic gain.”, in answer to our first key question. This additional value is the basic motivation for the merger. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-31 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions Your answer to Question 2 will be determined by the terms of the merger. What is the cost of the merger to Cislunar and its shareholders? Targetco’s shareholders will not accept less than $16 per share for their holdings. Assume that Cislunar offers them $19 per share. What is the cost to Cislunar and its shareholders? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-32 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions At $19 a share, Targetco’s shareholders capture $7.5 m of the economic gain: (2.5 m shares x $19/share) - $40 m market value = $47.5 m - $40 m = $7.5 m If Targetco’s shareholders get $7.5 m of the economic gain, then Cislunar’s must get $12.5 m of it: $20 m - $7.5 m = $12.5 m copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-33 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions Thus, the post-merger value of Cislunar should be $492.5 m. This may be derived as follows: Cislunar market value before: + Targetco market value before: + PV gain to merger - Cash paid to Targetco shareholders = Post merger market value: $480 m $40 m $20 m -$47.5 m $492.5 m copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-34 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions To summarize, this merger makes sense for Cislunar because: 1. It adds $20 m to overall value, i.e., the two firms are worth more together than apart. 2. The merger makes Cislunar’s shareholders better off. Taretco’s shareholders capture only $7.5 m of the $20 m increase in value, leaving $12.5 m for Cislunar’s shareholders. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-35 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions But, what happens if Cislunar wants to conserve cash and instead, pays Targetco’s shareholders with new Cislunar shares? This is the same merger, with $20 m of economic gain, but with different financing. What is the answer to our two questions in this case? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-36 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions If you look at the bottom of the second column of Table 23.4 on page 693, you will see the answer: Cislunar is worth $540 m after the merger, which is $47.5 m more than under the all cash offer. Why? Cislunar gets to keep $47.5 m in cash that it had previously given to Targetco’s shareholders. nd line down – cash is $57.5 m in this Look at the 2 scenario, versus $10 m in the previous one. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-37 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions However, there are now 833,333 new Cislunar shares outstanding: Since Cislunar’s shares were trading at 3x the price of Targetco’s, Cislunar had to issue 3 shares for each Targetco share. 2.5 m Targetco shares 3 = 833,333 shares Under the all cash offer, Cislunar’s shares are worth $49.25 post merger. Using a share exchange, Cislunar’s shares are worth $49.85 post merger or $0.60 more. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-38 Evaluating Mergers • Key Questions Why do Cislunar’s shareholders do better from the share exchange? With the cash offer, Cislunar’s shareholders gave-up $7.5 m of the economic gain to Targetco’s shareholders. However, with the share offer, they give up: 833,333 shares x $49.85/share - $40 m = $41.5 m - $40 m = $1.5 m Thus, Cislunar’s shareholders capture more of the economic gain with the share exchange, than they did with the cash offer. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-39 Merger Tactics • Unfriendly Takeovers Some mergers are friendly; however, some are called “hostile”. In a hostile merger, the managers of the target company fight the “unwelcome” offer from the acquiring company. A number of tactics have developed in the M&A business for such hostile mergers. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-40 Merger Tactics • Unfriendly Takeovers Shareholders’ rights plan or poison pill. Measures taken by the target firm to avoid acquisition by an unwelcome bidder. For example, giving existing shareholders the right to buy additional shares at an attractive price if a bidder acquires a significant holding. White knight Friendly potential acquirer sought by a target company that is threatened by an unwelcome bidder. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-41 Merger Tactics • Unfriendly Takeovers Shark repellant Amendments to a company charter that make it more difficult for a successful bidder to get control of the Board of Directors. For example, staggering the election of the Directors so that 1/3 get elected each year. This means the bidder cannot obtain majority control of the Board immediately after acquiring a majority of the shares. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-42 Summary of Chapter 23 If a company’s managers are under-performing, there are 4 ways to effect changes: A proxy battle. Acquisition of the firm by another firm. Acquisition of the firm by a private group of investors in an LBO. Divestiture of the firm. There are 3 ways for a firm to acquire another: It can merge all the assets and liabilities of the target into its own company. It can acquire the stock of the target. It can buy the assets of the target. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-43 Summary of Chapter 23 It makes sense for companies to merge when there is an economic gain from the transaction. This may occur because inefficient management is replaced or because there are synergies involved in the acquisition. Some sources of synergy are: Increased revenues. Economies of scale. Economies of vertical integration. Complementary resources Reduced Taxes. Redeployment of surplus funds. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 23-44 Summary of Chapter 23 We do not know how frequently these benefits occur, but they do make economic sense as reasons for a merger. Sometimes mergers are undertaken to diversify risks or to artificially inflate growth of eps. These motives are of dubious value in justifying a merger. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited