Week-1 - OSU Chemistry

advertisement

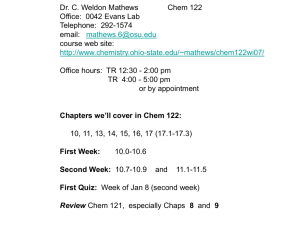

Dr. C. Weldon Mathews Office: 0042 Evans Lab Telephone: 292-1574 email: mathews.6@osu.edu Chem 122 web: www.chemistry.ohio-state.edu/~mathews/ Office hours: TR 12:30 - 2:00 pm TR 4:00 - 5:00 pm or by appointment Chapters we’ll cover in Chem 122: 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 (17.1-17.3) First Week: 10.0-10.6 Second Week: 10.7-10.9 and 11.1-11.4 First Quiz: Week of Jan 17 (third week) Review Chem 121, especially Chaps 8 and 9 Expectations: Develop a working knowledge of the topics. Bloom’s Taxonomy Knowledge – Simple recall of facts Comprehension – Translate into your own words or equations. Application – Apply concepts to specific situations; recognizing and solving a problem when the equations are not given. Analysis – Application plus recognition of important parts of problem. Synthesis – Assemble components into a form new to them, i.e. design a research plan or devise a synthetic scheme. Evaluation – Judge the value of materials in terms of internal and external criteria. Grossly abbreviated adaptation from Bloom, B. S. (Ed.) (1956) Taxonomy of educational objectives;: The classification of educational goals: Handbook I, cognitive domain. New York; Toronto: Longmans, Green see also http://www.counc.uvic.ca/learn/program/hndouts/bloom.html Study Habits and Study Resources: a) “Lectures” and “Reading” - minimal impact by themselves b) “Chemistry is not a Spectator Sport!” Prof. Janet Tarino, OSU Mansfield c) Recitation and Laboratory TAs d) Ask questions and seek help whenever you need it! e) Web resources: http://www.chemistry.ohio-state.edu /~mathews/chem122/ /~rbartosz/ /~rzellmer/ chemistry ->Undergraduate Program->Interactive Tutorials First Lab Experiment: Stoichiometry and Gas Volume 2 KClO3 (s) ------------------- 2 KCl (s) + 3 O2 (g) Apparatus is simple, shown in the next slide Depends on the Ideal Gas Equation, PV = nRT Recall some of the results of applying this simple equation PV = constant P/T = constant These results work extremely well ... OR DO THEY??? Pause Chapte r 10 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Begin 2nd week ? 9.8 9.9 Gases Characteristics of Gases Pressure Atmosopheric Pressure and the Barometer The Gas Laws The Pressure-Volume Relationships: Boyle’s Law The Temperature-volume Relationship: Charles’s Law The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law The Ideal-Gas Equation Relating the Ideal-Gas Equation and the Gas Laws Further Applications of the Ideal-Gas Equation Gas Densities and Molar Mass Volumes of Gases in Chemical Reactions Gas Mixtures and Partial Pressures Partial Pressures and Mole Fractions Collecting Gases over Water Kinetic-Molecular Theory Application to the Gas Laws Molecular Effusion and Diffusion Graham’s Law of Effusion Diffusion and Mean Free Path Real Gases: Deviations from Ideal Behavior The van der Waals Equation 10.1 Characteristics of Gases • Gases are highly compressible and occupy the full volume of their containers. • Contrast with liquids and solids. • When a gas is subjected to pressure, its volume changes. • Gases always form homogeneous mixtures with other gases. • Gases only “use” about 0.01 % of the volume of their containers. Characteristics of Gases 10.2 Pressure • Pressure is the force acting on an object per unit area: F P A • Gravity exerts a force on the earth’s atmosphere • A column of air 1 m2 in cross section exerts a force of 105 N. • The pressure of a 1 m2 column of air is about 100 kPa. Pressure F P A F = ma = (104 kg)(9.8m/s2) = 1 x 105 kg-m/s2 = 1 x 105 N F 1 x 105 N P A 1 m2 P = 1 x 105 N/m2 = 1 x 105 Pa = 1 x 102 kPa = Newton Pressure • • • • • Atmosphere Pressure and the Barometer SI Units: 1 N = 1 kg.m/s2; 1 Pa = 1 N/m2. Atmospheric pressure is measured with a barometer. If a tube is inserted into a container of mercury open to the atmosphere, the mercury will rise 760 mm up the tube. Standard atmospheric pressure is the pressure required to support 760 mm of Hg in a column. Units: 1 atm = 760 mmHg = 760 torr = 1.01325 105 Pa = 101.325 kPa. In our discussions about gases, we’ll often use the gas cylinder with a movable piston as a helpful analogy. You also may think of a bicycle pump as an example. Pressure Atmosphere Pressure and the Barometer Notice that the top end of the BAROMETER is closed and that a “Torricelli VACUUM” exists above the mercury. Pressure Atmosphere Pressure and the Barometer • The pressures of gases not open to the atmosphere are measured in manometers. • A MANOMETER consists of a bulb of gas attached to a U-tube containing Hg: – If Pgas < Patm then Pgas + Ph2 = Patm. – If Pgas > Patm then Pgas = Patm + Ph2. Note that Ph may be positive or negative! Pressure Notice again the various units that may be used to measure Pressure: Easiest to refer to the ‘Standard Atmospheric Pressure’ which is defined as 1 atm 1 atm = 101.325 kPa = 1.01325 x 105 Pa = = 760 mmHg = 760 torr And, this relationship will help you recall the conversion factors between the various units. End of Lecture, 1/4/2005 10.3 The Gas Laws • • • • • The Pressure-Volume Relationship: Boyle’s Law Weather balloons are used as a practical consequence to the relationship between pressure and volume of a gas. As the weather balloon gets further from the earth’s surface, the atmospheric pressure decreases. As a consequence, the volume of the balloon increases. Boyle’s Law: the volume of a fixed quantity of gas is inversely proportional to its pressure. Boyle used a manometer to carry out the experiment. The Gas Laws The Pressure-Volume Relationship: Boyle’s Law • Mathematically: 1 k V constant P P PV constant PV k • A plot of V versus P is a hyperbola. • Similarly, a plot of V versus 1/P must be a straight line passing through the origin. The Gas Laws The Pressure-Volume Relationship: Boyle’s Law VP = k V = k/P The Gas Laws The Temperature-Volume Relationship: Charles’s Law • We know that hot air balloons expand when they are heated. • Charles’s Law: the volume of a fixed quantity of gas at constant pressure increases as the temperature increases. • Mathematically: V constant T kT V constant k T These are typical of observations you might make in the lab. Notice that on this plot the equation is of the form y = a + b x and the volume does NOT go to 0 at x = 0 !!! The Gas Laws • • • • • The Temperature-Volume Relationship: Charles’s Law A plot of V versus T is a straight line. When T is measured in C, the intercept on the temperature axis is -273.15C. We define absolute zero, 0 K = -273.15C. Note the value of the constant reflects the assumptions: of a constant amount of gas and pressure. And now the equation is of the form y = bx , i.e. a = 0. The Gas Laws The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law • Gay-Lussac’s Law of combining volumes: at a given temperature and pressure, the volumes of gases which react are ratios of small whole numbers. The Gas Laws The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law • Avogadro’s Hypothesis: equal volumes of gas at the same temperature and pressure will contain the same number of molecules. • Avogadro’s Law: the volume of gas at a given temperature and pressure is directly proportional to the number of moles of gas. The Gas Laws The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law • Mathematically: V constant n kn • We will show that 22.4 L of any gas at 0 C and 1 atm contain 6.02 1023 gas molecules = 1 mole of molecules. The Gas Laws The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law 10.4 The Ideal Gas Equation • Consider the three gas laws. 1 V (constant n, T ) • Boyle’s Law: P • Charles’s Law: V T (constant n, P) • Avogadro’s Law: V n (constant P, T ) • We can combine these into a general gas law: nT nT V k P P The Ideal Gas Equation • If the k is now defined as R, the proportionality constant of (called the gas constant), then nT V R P • The ideal gas equation is: PV nRT • R = 0.08206 L·atm/mol·K = 8.314 J/mol·K But how can you derive the value of R? Recall this slide and how to convert grams to moles. The Gas Laws The Quantity-Volume Relationship: Avogadro’s Law The Ideal Gas Equation • We define STP (standard temperature and pressure) = 0C, 273.15 K, 1 atm. • And now we see the volume of 1 mol of gas at STP is: PV nRT nRT 1 mol 0.08206 L·atm/mol·K 273.15 K V 22.41 L P 1.000 atm ( notice the “>” should be a “ / “ ) Fig. 10.12 shows the actual results for a number of gases. Notice that the “ideal gas model” does a pretty good job. The Ideal Gas Equation Relating the Ideal-Gas Equation and the Gas Laws • If PV = nRT and n and T are constant, then PV = constant and we have Boyle’s law. • Other laws can be generated similarly. • In general, if we have a gas under two sets of conditions, then P1V1 P2V2 n1T1 n2T2 10.5 Further Applications of the Ideal-Gas Equation Gas Densities and Molar Mass • Density has units of mass over volume. • Rearranging the ideal-gas equation with M as molar mass we get PV nRT n P V RT nM PM d V RT has units of mol·L-1 And now the units are g·L-1 Further Applications of the Ideal-Gas Equation Gas Densities and Molar Mass • The molar mass of a gas can be determined as follows: dRT M P Volumes of Gases in Chemical Reactions • The ideal-gas equation relates P, V, and T to number of moles of gas. • The n can then be used in stoichiometric calculations. Further Further Applications Applications of of the the Ideal-Gas Ideal-Gas Equation Equation Volumes of Gases in Chemical Reactions Consider now the application of these ideas to chemical reactions. eg, 2 NaN3 (s) 2 Na + 3 N2 (g) Given the mass of sodium azide that reacts, the number of moles of nitrogen gas generated may be calculated. From this, the volume may be calculated at a given temperature and pressure. What volume of gas at 760 torr and 0 oC would be generated from 32.51 g of sodium azide which decomposes according to the equation 2 NaN3 (s) 2 Na + 3 N2 (g) ? In order to answer this question, we need to know how many moles of nitrogen will be generated (see Chem 121). Then we apply the ideal gas law. 1 mol NaN3 3 mol N 2 0.75 mol N 2 32.51 g NaN3 65.02 g NaN3 2 mol NaN3 nRT P 0.75 mol N 2 0.0821 L atm / mol K 273 K 16.81 L of N gas or V 2 1 atm PV nRT yields the equation V (Sorry about the mistake given in lecture!) 10.6 Gas Mixtures and Partial Pressures • Since gas molecules are so far apart, we can assume they behave independently. • Dalton’s Law: in a gas mixture the total pressure is given by the sum of partial pressures of each component: Ptotal P1 P2 P3 • Each gas obeys the ideal gas equation: RT Pi ni V Gas Mixtures and Partial Pressures • Combing the equations RT Ptotal n1 n2 n3 V Partial Pressures and Mole Fractions • Let ni be the number of moles of gas i exerting a partial pressure Pi, then Pi i Ptotal where i is the mole fraction (ni/nt). A mixture of gases containing 0.538 mol He(gas 1), 0.315 mol Ne (gas2), and 0.103 mol Ar (gas 3) is confined in a 7.00-L vessel at 25 0C. (a) Calculate the partial pressure of each gas. (b) Calculate the total (b) pressure in the vessel. (c) Calculate the mole fraction of each gas. P1 = n1 RT / V = (0.538 mol)(0.0821 L-atm/mol-K)(298 K) / (7.00 L) = 1.88 atm of He similarly, P2 = 1.10 atm of Ne, and P3 = 0.360 atm Ar The total pressure is just PT = P1 + P2 + P3 = ∑ Pi = 1.88 + 1.10 + 0.360 = 3.34 atm The mole fraction of He is X1 = P1 / PT = 1.88/3.34 = 0.563 (This also could be obtained from X1 = n1 / nT = 0.538/0.956 Likewise, X2 = 0.329 and X3 = 0.108 note that ∑ Xi = 1.00 always (within error limits): 0.563 + 0.329 + 0.108 = 1.00 Gas Mixtures and Partial Pressures Collecting Gases over Water • It is common to synthesize gases and collect them by displacing a volume of water. • To calculate the amount of gas produced, we need to correct for the partial pressure of the water: Ptotal Pgas Pwater Gas Mixtures and Partial Pressures Collecting Gases over Water 10.7 Kinetic Molecular Theory • Theory developed to explain gas behavior. • Theory based on properties at the molecular level. • Assumptions: – Gases consist of a large number of molecules in constant random motion. – Volume of individual molecules negligible compared to volume of container. – Intermolecular forces (forces between gas molecules) negligible.