Hedging Overview - Trinity University

advertisement

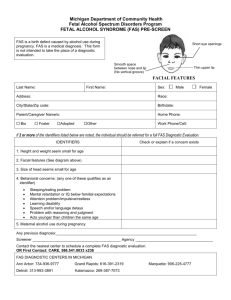

Fair Value Accounting FAS 105, 107, 115, 130, 133, 141, 142, 155, 157, 159 Bob Jensen Emeritus Professor of Accounting Trinity University in San Antonio 190 Sunset Hill Road Sugar Hill, NH 03586 603-823-8482 rjensen@trinity.edu http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/ Bob Jensen’s Summary of Accounting History and Theory http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/theory.htm “Not everything that can be counted, counts. And not everything that counts can be counted.” Albert Einstein 1-0 1-1 1-2 1-3 1-4 1-5 1-6 The government gave them 105% for their $200,000 subprime mortgage. They then sold the house for $37,000, got married, and are escaping from California. 1-7 So are we now that we flipped the doghouse! 1-8 Alternative Accounting Measures of Value of Assets and Liabilities “Skate to where the puck is going, not to where it is.” Wayne Gretsky (as quoted for many years by Jerry Trites ) Historical Cost of Individual Assets and Liabilities Summed in Balance Sheet (Book Value) Historical Cost With Price Level Adjustments (PLA) Entry Value (Replacement Cost, Current Cost) 1-9 Alternative Accounting Measures of Value of Assets and Liabilities “Skate to where the puck is going, not to where it is.” Wayne Gretsky (as quoted for many years by Jerry Trites ) Exit Value (Net Liquidation Value) Economic Value (Discounted Cash Flows, FCF, Residual Income) Market Value of Entire Firm (Cash Versus Stock Trade) Market Value of All Shares Outstanding 1-10 Alternative Accounting Measures of Value of Assets and Liabilities Skate to where the puck is going, not to where it is. Wayne Gretsky (as quoted for many years by Jerry Trites ) Graduate student Derek Panchuk and professor Joan Vickers, who discovered the Quiet Eye phenomenon, have just completed the most comprehensive, on-ice hockey study to determine where elite goalies focus their eyes in order to make a save. Simply put, they found that goalies should keep their eyes on the puck. In an article to be published in the journal Human Movement Science, Panchuk and Vickers discovered that the best goaltenders rest their gaze directly on the puck and shooter's stick almost a full second before the shot is released. When they do that they make the save over 75 per cent of the time. "Keep your eyes on the puck," PhysOrg, October 26, 2006 --http://physorg.com/news81068530.html 1-11 1-12 FAS 33 from 1979-1984 (ended with FAS 82) 1-13 Knotted Strings South American Indian culture apparently used layers of knotted strings as a complicated ledger. Two Harvard University researchers believe they have uncovered the meaning of a group of Incan khipus, cryptic assemblages of string and knots that were used by the South American civilization for record-keeping and perhaps even as a written language. Researchers have long known that some knot patterns represented a specific number. Archeologist Gary Urton and mathematician Carrie Brezine report today in the journal Science that computer analysis of 21 khipus showed how individual strings were combined into multilayered collections that were used as a kind of ledger. Thomas H. Maugh, "Researchers Think They've Got the Incas' 1-14 Numbers," Los Angeles Times, August 12, 2005 Origins of Double Entry Accounting are Unknown 1300s A.D. crusades opened the Middle East and Mediterranean trade routes Venice and Genoa became venture trading centers for commerce 1296 A.D. Fini Ledgers in Florence 1340 City of Massri Treasurers Accounts are in Double Entry form. 1494 Luca Pacioli's Summa de Arithmetica Geometria Proportionalita (A Review of Arithmetic, Geometry and Proportions) 1-15 Going Concern and Accrual Accounting Evolved in the 1500s Venture accounting over the life of a venture with interim statements evolved in The Netherlands 1673 Code of Commerce in France requires biannual balance sheet reporting Charge and Discharge Agency Responsibility and Stewardship Accounting in English trust accounting 1-16 Limited liability Corporations (divorced professional management from ownership shares) 1555 A.D. Russia Company 1600 A.D. East India Company 1670 A.D. Hudson's Bay Company England's Joint Stock Companies Act of 1844 required depreciation accounting for railroads, mining, and manufacturing (although the concept of depreciation dates back to Roman times). 1-17 Speculation Fever and Stewardship Fraud and corruption festered and grew with the trading of joint stock, especially after 1600 A.D. The South Seas Company scandal (reporting stock sales as income and paying dividends out of capital) led to England's Bubble Act in 1720 A.D. that focused on misleading accounting practices that helped managers rip off investors, especially by crediting stock sales to income. 1-18 Laissez-Faire Accounting survived endless debates and scandals until the Great Depression in 1933 Much of the debate focused on capital maintenance (e.g., failure to charge off depreciation and failure to provide for replacement of operating assets), but governments did not legally impose auditing requirements and serious GAAP until the U.S. securities laws in the early 1930s. Accountants were vocal in reform movements, but governments were slow to react with legislation and courts failed to establish consistent GAAP. Creation of the SEC in an effort to regain public trust in financial reporting and equity investing. Many firms did have independent audits and conformed to the best GAAP traditions of the day (thereby giving some evidence that Agency Theory works sometimes.) Agency theory hypothesizes that it is in the best interest of management to contract for protection of investors and avoid scandalous asymmetries of information. 1-19 After 1933, the AICPA and the SEC seriously attempted to generate accounting standards, enforce accounting standards, and provide academic justification for promulgated standards. ASRs of the SEC In a 3-2 vote the SEC followed George O. May's efforts to mandate external audits of securities traded across state lines in the U.S. 1939-1959 A.D.: Accounting standards were generated by the AICPA's Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP) that issued Accounting Research Bulletins (51 ARBs) --- but the tendency was to overlook controversial issues such as off-balance sheet financing, public disclosure of management forecasts, price-level accounting, current cost accounting, and exit value accounting. Controversial items avoided by the CAP included management compensation accounting, pension accounting, post-employment benefits accounting, and off balance sheet financing (OBSF). The CAP did very little to restrain diversity of reporting. 1-20 After 1933, the AICPA and the SEC seriously attempted to generate accounting standards, enforce accounting standards, and provide academic justification for promulgated standards. 1960-1972 A.D.: Accounting standards in the U.S. were generated by the AICPA's Accounting Principles Board (APB) that had more members than the CAP and a mandate to attack more controversial reporting issues. The APB attacked some controversial issues but often failed to resolve their own disputes on such issues as pooling versus purchase accounting for mergers. 1972-???? A.D. Accounting standards in the U.S. were, and still are, being generated by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) that has seven members, including required members from industry, academe, and financial analysts in addition to members from public accountancy. FASB members must divorce themselves from previous income ties and work full time for the FASB. The formation of the FASB was a desperation move by CPA's to stave off threatened takeover of accounting standards by the Federal Government (there were the Moss and Metcalf bills to do just that under pending legislation in the U.S. House and Senate). Unlike the CAP and APB, the FASB has a full-time research staff and has issued highly controversial standards forcing firms to abide by pension accounting rules, capitalization of many leases, and booking of many previous OBSF items (capital leases, pensions, post-employment benefits, income tax accounting, derivative financial instruments, pooling accounting, etc.). The road has been long and hard on some other issues where attempts to issue new standards (e.g., expensing of dry holes in oil and gas accounting and booking of employee stock options) have been thwarted by highly-publicized political pressuring by corporations. 1-21 In 2007 International Harmonization is Becoming a Reality In Year 2008 foreign corporations may file reports with the SEC and be listed on U.S. stock exchanges using IASB standards rather than FASB standards without reconciling the two. The U.S., Canada, and other nations are working toward adoption of IASB standards in place of domestic accounting standards. 1-22 Fair Value Accounting Under the IASB & FASB IASB is exploring with FASB accounting for fair-value accounting as part of a wider project on measurement. It is in the context of this long-planned effort, and not some recent reaction, that the IASB is planning to and will explore issues related to fair-value accounting. IAS 32 and 39 Require Fair Value Accounting for Financial Instruments in Many Instances 1-23 Fair Value Accounting Under the IASB & FASB The main problem of fair value adjustment is that many (most?) of the adjustments cause enormous fluctuations in earnings, assets, and liabilities that are washed out over time and never realized. The main advantage is that interim impacts that “might be” realized are booked. It’s a war between “might be” versus “might never.” The war has been waging for over a century with respect to booked assets and two decades with respect to unbooked derivative instruments, contingencies, and intangibles. 1-24 1-25 Fair Value Accounting Under the IASB & FASB Holder, Hopkins, and Wablen (The Accounting Review, 2004, pp. 453-472) found, in a sample of 200 banks, that fair value accounting gave rise to more than five times more earnings volatility than traditional GAAP earnings. Much of the volatilty washes out over time such that earnings increases and decreases from fair value adjustments have zero effect on cash in most instances. This is misleading for going concerns. 1-26 Fair Value Accounting Under the IASB & FASB Hirst and Hopkins (Journal of Accounting Research, 1998, pp. 4775) found, in a sample of 200 banks, that fair value accounting improved bank equity analyst judgments about risk and value. Ahmed, Kilic, and Lobo (The Accounting Review, 2006, pp. 567588) found that fair value booking of derivatives after FAS 133 was far more important than mere disclosures in footnotes for banking financial statements. More study needed for non-financial business firms. 1-27 Fair Valuing Debt Better/Worse Credit Standing = Loss/Gain Barge (James Barge, senior vice president and controller for Time Warner) also cited as problematic the hypothetical case of a company whose creditworthiness is downgraded by the rating agencies. By marking down the debt's value on its balance sheet, the company would realize more income, a scenario Barge called "nonsensical." He warned of a host of such effects arising under fair value when a company changes its capital structure. 1-28 Fair Valuing Debt Better/Worse Credit Standing = Loss/Gain Actually there is potential gain from buying back debt cheaper due to lowered credit rating. Actually there is potential loss from buying back debt cheaper due to improved credit rating. Chasteen and Ransom (Acctg. Horizons, June 2007, pp. 119-136) advocate immediate recognition of such gains & losses and future carrying of debt at risk free rates. 1-29 Fair Value Accounting Under the IASB & FASB Barge also cited where the acquisition of intangible assets that a company does not intend to use as a further example of fair value's potentially worrisome effects. Under current GAAP, their value is included in goodwill and subject to annual impairment testing for possible write-off. But if, as FASB is contemplating, the value of those assets would be recorded on the balance sheet along with that of the associated tangible assets that were acquired, Barge worries that an immediate write-off would then be required — even though it would not reflect the acquiring company's economics. 1-30 Key FASB Standards on Fair Value Acctg. FAS 105 --- Disclosure of OBSF and market risks of instruments FAS 107 --- Requirements for disclosure of FV FAS 115 --- HTM vs. AFS vs. Trading FAS 130 --- OCI offset instead of current earnings FAS 133 --- FV required for derivative instruments FAS 141 --- Identify and FV intangibles in acquisitions FAS 142 --- Must est. FV of “Goodwill” remaining FAS 155 --- Requires FV acctg. for hybrid securities FAS 157 --- Defines FV and hierarchy of meas. pref. FAS 159 --- FVO for financial instruments 1-31 "How to Save the Financial System," by William M. Isaac, The Wall Street Journal, September 19, 2008 Suspend the Fair Value Accounting rules “Biggest culprit for banking collapse” is FAS 115 that in bad times requires markdowns to “fire sale” values Clamp down on abuses by short sellers Short sellers are engaged in abuses such as purchasing credit default swaps on corporate bonds (essentially bets on whether a borrower will default) Withdraw the Basel II capital rules (2007) Allow high leverage capital ratios in good times, but require much higher ratios for banks losing money. 1-32 Key FASB Standards on Fair Value Acctg. FAS 105 --- 1990 FAS 107 --- 1991 to be effective in 1993 FAS 115 --- 1993 to be effective in 1994 FAS 130 --- 1997 to be effective in 1998 FAS 133 --- 1998 but later delayed until 2000 FAS 141 --- 2001 FAS 142 --- 2001 FAS 155 --- 2006 FAS 157 --- 2006 FAS 159 --- 2007 to be effective in 2008 1-33 FAS 105 in 1990 Disclosure of OBSF Market and Credit Risk The face, contract, or notional principal amount The nature and terms of the instruments and a discussion of their credit and market risk, cash requirements, and related accounting policies The accounting loss the entity would incur if any party to the financial instrument failed completely to perform according to the terms of the contract and the collateral or other security, if any, for the amount due proved to be of no value to the entity The entity's policy for requiring collateral or other security on financial instruments it accepts and a description of collateral on instruments presently held. This Statement also requires disclosure of information about significant concentrations of credit risk from an individual counterparty or groups of counterparties for all financial instruments. 1-34 FAS 107 effective in 1993 Disclosure of Fair Value of Fin. Instruments This Statement extends existing fair value disclosure practices for some instruments by requiring all entities to disclose the fair value of financial instruments, both assets and liabilities recognized and not recognized in the statement of financial position, for which it is practicable to estimate fair value. If estimating fair value is not practicable, this Statement requires disclosure of descriptive information pertinent to estimating the value of a financial instrument. Disclosures about fair value are not required for certain financial instruments listed in paragraph 8. 1-35 FAS 115 effective in 1994 FV Reporting of AFS Investments in Debt/Equity Debt securities that the enterprise has the positive intent and ability to hold to maturity are classified as held-to-maturity securities and reported at amortized cost. Debt and equity securities that are bought and held principally for the purpose of selling them in the near term are classified as trading securities and reported at fair value, with unrealized gains and losses included in earnings. Debt and equity securities not classified as either held-to-maturity securities or trading securities are classified as available-for-sale securities and reported at fair value, with unrealized gains and losses excluded from earnings and reported in a separate component of shareholders' equity. 1-36 FAS 130 effective in 1998 Reporting Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) This Statement requires that an enterprise (a) classify items of other comprehensive income by their nature in a financial statement and (b) display the accumulated balance of other comprehensive income (AOCI) separately from retained earnings and additional paid-in capital in the equity section of a statement of financial position. 1-37 FAS 133 effective in 2000 Amended by FAS 137, 138, 149, 155, and 159 Accounting for Derivative Financial Instruments and Hedging Activities Financial Derivatives & Scandals Explode in the Early 1990's Video or Audio clip from CBS Sixty Minutes SIXTY01.avi or SIXTY01.mp3 Audio clip from John Smith of Deloitte & Touche in August 1994 SMITH01.mp3 Examples of derivative contracts that even the professional analysts could not decipher The derivatives that Merrill Lynch wrote that drive Orange County into bankruptcy Other derivatives fraud summaries are at http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/fraud.htm#DerivativesFraud Video and audio clips of FASB updates on FAS 133 Audio 1 --- Dennis Beresford in 1994 in New York City BERES01.mp3 Audio 2 --- Dennis Beresford in 1995 in Orlando BERES02.mp3 Derivative Financial Instrument Frauds --- Off line --- Click Here 1-38 FAS 133 effective in 2000 Amended by FAS 137, 138, 149, 155, and 159 Accounting for Derivative Financial Instruments and Hedging Activities Requires booking of most derivative financial instruments at fair value (with some exceptions for NPNS, regular-way, insurance contracts, weather derivatives, short sales, interest-strips, etc.) Derivatives are to be marked to current fair value at least every 90 days and on reporting dates. Changes in fair value are to be charged or credited to current earnings unless the derivatives qualify for hedge accounting treatment as cash flow, fair value, or FX hedges. Not all economic hedges qualify for hedge accounting relief from current earnings. Hedge accounting rules under FAS 133 and its amendments are very complex. 1-39 Key FAS 133 and IAS 39 Terms Notional | Underlying | Net Settlement | Little or No Initial Investment Financial Instrument | Derivative Instrument Purchase Commitment | Firm Commitment | Forecasted Transaction | Speculation Stand Alone | Cash Flow Hedge | Fair Value Hedge | FX Hedge Purchased Options | Written Options | Long Forwards | Short Forwards | Swaps | Futures Contracts European versus American versus Asian options Spot Price, Forward Price, Strike Price, Premium, Intrinsic Value, Time Value Freestanding, Embedded, Structured (tailormade rather than convential financing) OCI versus Firm Commitment | Delta 1-40 FAS 141 effective in 2001 Purchase Method Req. for Business Combinations In contrast to Opinion 16, which required separate recognition of intangible assets that can be identified and named, this Statement requires that they be recognized as assets apart from goodwill if they meet one of two criteria—the contractual-legal criterion or the separability criterion. To assist in identifying acquired intangible assets, this Statement also provides an illustrative list of intangible assets that meet either of those criteria. In addition to the disclosure requirements in Opinion 16, this Statement requires disclosure of the primary reasons for a business combination and the allocation of the purchase price paid to the assets acquired and liabilities assumed by major balance sheet caption. When the amounts of goodwill and intangible assets acquired are significant in relation to the purchase price paid, disclosure of other information about those assets is required, such as the amount of goodwill by reportable segment and the amount of the purchase price assigned to each major intangible asset class. 1-41 FAS 142 effective in 2001 Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets Acquired Purchased goodwill and other intangibles in business combinations are to be revalued each reporting date and written down to the extent that its historical cost valuation has been impaired. The historical cost is no longer to be amortized except in the case of intangibles with finite lives. In theory the cost of purchased intangibles could stay on the books for many, many years. This Statement provides specific guidance for testing goodwill/ingangibeles for impairment. Goodwill will be tested for impairment at least annually using a two-step process that begins with an estimation of the fair value of a reporting unit. The first step is a screen for potential impairment, and the second step measures the amount of impairment, if any. However, if certain criteria are met, the requirement to test goodwill for impairment annually can be satisfied without a re-measurement of the fair value of a reporting unit. 1-42 FAS 155 effective in 2006 Accounting for Certain Hybrid Financial Instruments Permits fair value re-measurement for any hybrid financial instrument that contains an embedded derivative that otherwise would require bifurcation Clarifies which interest-only strips and principal-only strips are not subject to the requirements of Statement 133 Establishes a requirement to evaluate interests in securitized financial assets to identify interests that are freestanding derivatives or that are hybrid financial instruments that contain an embedded derivative requiring bifurcation Clarifies that concentrations of credit risk in the form of subordination are not embedded derivatives Amends Statement 140 to eliminate the prohibition on a qualifying specialpurpose entity from holding a derivative financial instrument that pertains to a beneficial interest other than another derivative financial instrument. 1-43 FAS 155 Permits fair value measurement for certain hybrid financial instruments that contain an embedded derivative that would otherwise require bifurcation under Statement 133. Amends Statement 133 to require evaluation of all interests in securitized financial assets. thus eliminating the exemption in Statement 133 accounts for certain hybrid instruments. As a result, entities will have to determine if such interest may be: 1. Freestanding derivatives, 2. Hybrid financial instruments containing embedded derivatives requiring bifurcation, or 3. Hybrid financial instruments containing embedded derivatives that do not require bifurcation Clarifies that only the simplest and most direct separation of interest and principal cash flows need not be evaluated for embedded derivatives 1-44 FAS 155 Clarifies that concentrations of credit risk in the form of subordination are not embedded derivatives. Amends Statement 140 to allow a QSPE to hold passive derivative instruments that pertain to beneficial interest that are or contain a derivative financial instrument Irrevocable election on an instrument by instrument basis with all changes in fair value recognized in earnings. The fair value election should be made at the time the financial instrument is acquired, issued or there is a new basis in a previously recognized financial instrument. 1-45 Upon adoption, applies to existing hybrid financial instruments that had been bifurcated under the requirements of Statement 133. FAS 155 The Bifurcation Model Paragraph 12 of Statement 133: Yes No 2. Would the embedded feature be a derivative if it was freestanding? (Par 12c) No Do Not Bifurcate 1-46 Yes 3. Is it clearly and closely related to the Host contract? (Par 12a) Yes No Bifurcate 1. Is the hybrid carried at fair value through earnings? (Par 12b) FAS 155 Paragraph 14 of FAS 133 However, interest-only strips and principal-only strips are not subject to the requirements of this Statement provided they (a) initially resulted from separating the rights to receive contractual cash flows of a financial instrument that, in and of itself, did not contain an embedded derivative that otherwise would have been accounted for separately as a derivative pursuant to the provisions of paragraphs 12 and 13 and (b) do not incorporate any terms not present in the original financial instrument described above. 1-47 FAS 155 However, interest-only strips and principal-only strips are not subject to the requirements of this Statement provided those strips (a) represent the rights to receive only a specified proportion of the contractual interest cash flows of a specific debt instrument or a specified proportion of the contractual principal cash flows of that debt instrument and (b) do not incorporate any terms not present in the original financial debt instrument described above. An allocation of a portion of the interest or principal cash flows of a specific debt instrument as reasonable compensation for stripping the instrument or to provide adequate compensation to a servicer (as defined in Statement 140) would meet the intended narrow scope of the exception provided in this paragraph. However, an allocation of a portion of the interest or principal cash flows of a specific debt instrument to provide for a guarantee of payments, for servicing in excess of adequate compensation, or for any other purpose would not meet the intended narrow scope of the exception. 1-48 FAS 155 • Nullified Issue D1 Application of Statement 133 to Beneficial Interests in Securitized Financial Assets. Impact of Issue D1 was to defer the bifurcation requirements of Statement 133 • Holders of beneficial financial interests must analyze arrangements that govern the payoff structure and the subordination status of the financial instrument Prepayment risks in such structures could result in meeting the 13(b) requirements of Statement 133 1-49 FAS 157 effective in 2006 Fair Value Measurements The changes to current practice resulting from the application of this Statement relate to the definition of fair value, the methods used to measure fair value, and the expanded disclosures about fair value measurements. 1-50 FAS 157 All accounting pronouncements that require or permit fair value measurement and include such items as: Investment securities – Statement 115 Derivatives – Statement 133 “Short sales” of securities – AICPA Audit Guides for certain industries 1-51 Investments carried at fair value by investment companies Certain assets and liabilities measured at fair value in a business combination – Statement 141: Intangible assets In process R&D Assets measured at fair value for an impairment test – Statements 142 and 144: Long-lived assets held for sale Reporting units Goodwill Differences Between Statement 157 and Current Practice 1-52 Issue Current Practice Statement 157 Definition Various definitions of fair value – Amount at which an asset or liability could be bought or sold in a current transaction between willing parties, that is, other than in a forced liquidation sale Price that would be received for an asset or paid to transfer a liability between market participants at the measurement date. Transaction Entry Price Presumed equal to fair value May not be representative of fair value; provides indicators of when the transaction price may not be fair value. Highest and Best Use Current practice is to value assets in continued use unless identified for disposition Independent of the reporting entity’s intent: considered from market participant perspective Use of Market Data in Valuations Use of market data encouraged. In some circumstances entity intent permitted to be considered in valuations. Valuation techniques must maximize use of market observable data and minimize use of unobservable data Hierarchy No current mandated hierarchy. Three levels distinguished between observable and unobservable inputs. SOURCE: DELOITTE Differences Between Statement 157 and Current Practice Issue Current Practice Statement 157 Defensive Value - New concept Principal/Most Advantageous Market - Newly defined concept Market Participants Current guidance on market participants is unclear. Buyer-specific intent may be considered Buyer-specific intent should be dismissed if different from that of other multiple market participants Block Discounts Broker-dealers and investment companies permitted to apply block discounts Eliminated for all companies in relation to actively traded securities Restricted Securities Restrictions on marketable securities not required to be considered in the valuation if the restriction terminated within one year. Fair value measurement should include the effect of a restriction, if the restriction is an attribute of the security which would pass to market participants. Model Risk 1-53 SOURCE: DELOITTE - Assessed as a component of the fair value measurement Statement 157 – Valuation Hierarchy Statement 157 provides three main approaches to measuring fair value. Fair Value Hierarchy Level 3 Level 1 Level 2 Market- based Extrapolate Objective 1-54 Income/FCF Model Subjective FAS 157 Level 1 Inputs --- Paragraphs 24-27 Quoted prices of identical items in active markets (full rather than thin markets) Fungible goods No timing distress Options versus commodities markets 1-55 FAS 157 Level 2 Inputs --- Extrapolations from Markets or Sales a. Quoted prices for similar assets or liabilities in active markets or reliable component cost markets. b. Quoted prices for identical or similar assets or liabilities in markets that are not active, that is, markets in which there are few transactions for the asset or liability, the prices are not current, or price quotations vary substantially either over time or among market makers (for example, some brokered markets), or in which little information is released publicly (for example, a principal-to principal market) c. Inputs other than quoted prices that are observable for the asset or liability (for example, interest rates and yield curves observable at commonly quoted intervals, volatilities, prepayment speeds, loss severities, credit risks, and default rates) d. Inputs that are derived principally from or corroborated by observable market data by correlation or other means (market-corroborated inputs). 1-56 FAS 157 Level 2 Inputs (Examples) a. OTC swaps, options, and forward contracts Extrapolations from Bloomberg databases b. Appraisals based on similar-item sales Such as real estate in the same neighborhood (Supposed to be full-market estimates rather than thin-market estimates such as a single offer) c. Jewelry value estimates based upon markets for components like gold in the jewelry 1-57 FAS 157 Level 2 Enron Energy Services (EES) Example a. Long-term contracts for power to companies such as Eli Lili. Stripper fanatic Lou Pai was CEO of EES. b. Enron sold 7% of EES to institutions for $130 million c. Enron thereafter valued EES at $1.9 billion and recorded a $61 million profit due to change in FV. d. Within two years most of EES contracts became liabilities totaling over $500 million. No write downs were taken until Enron declared bankruptcy. 1-58 FAS 157 Level 2 Enron Energy Services (EES) Example a. Fair value accounting may lead to unearned income being recognized up front. b. Fair value accounting may lead to inconsistencies between valuations upward vs. valuations downward c. Plunges CPA auditors into valuation’s stormy seas. CPAs have no special comparative advantages here! d. Assets may flip flop to liabilities and vice versa overnight 1-59 FAS 157 Level 3 Inputs in Paragraphs 30-32 Unobservable inputs shall reflect the reporting entity’s own assumptions about the assumptions that market participants would use in pricing the asset or liability (including assumptions about risk). Unobservable inputs shall be developed based on the best information available in the circumstances, which might include the reporting entity’s own data. In developing unobservable inputs, the reporting entity need not undertake all possible efforts to obtain information about market participant assumptions 1-60 FAS 157 Level 3 Expert Opinion and Value Models a. Residual Income (RI) and Free Cash Flow (FCF) Models (Highly sensitive to terminal values & perpetuity) (Highly sensitive to missing variables) (Intangibles are highly volatile) (Highly sensitive to non-stationarity) (Competition & Law destroys excess returns over time) b. Subjective appraisals with explicit analysis of underlying assumptions (Subjectivity leads to high variations in opinion) (Moral hazard --- scandalous S&L appraisals) (Value is so dependent upon unforeseeable events) 1-61 FAS 157 Level 3 Examples a. Bonds of a bankrupt firm b. Asset retirement obligation c. Pollution abatement obligation d. Enron’s booking of “fair value” of gas contracts 1-62 FAS 157 Level 3 Enron “Mark-to Market” Example a. Long-term contracts for gas to electric utilities such as Scithe Energies. b. Estimate gas profits over 10-20 years forward and record present value as an asset as current FV earnings. c. Increased gas price estimates increased value of asset and changes in FV taken into earnings. Eventually, the booked receivable from Scithe was $1.5 billion that could not possibly be collected ever. d. No write down took place until after Enron declared bankruptcy in December 2000. Huge bonuses, however, were paid to Enron executives all along. 1-63 FAS 157 Determining primary or most advantageous market Assigning and Monitoring Statement 157 hierarchy levels Credit 1-64 risk in valuing liabilities FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Allows entities to voluntarily choose to measure eligible financial instruments at fair value (the “fair value option”) (Exceptions for items covered by some other standards such as consolidated entities, pensions, post-employment contracts, leases, and financial insurance contracts) Changes in fair value recognized in earnings. (no OCI) Election made on an instrument-by-instrument basis Irrevocable 1-65 FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities FASB issued the FVO to: Provide an opportunity to mitigate volatility in earnings caused by a mixed attribute accounting model Reduce the need for applying complex hedge accounting provisions Expand the use of fair value measurements International convergence 1-66 FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Scope: • Recognized financial assets and liabilities (but not forecasted transactions under FAS 133) • Firm commitments that would otherwise not be recognized at inception and that involve only financial instruments • Written loan commitments • Certain rights and obligations under insurance contracts or warranty obligations • A financial host contract in a nonfinancial hybrid instrument • Certain nonfinancial assets and liabilities 1-67 FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Advantages: Eliminate arbitrary FAS 115 classifications that can be used by management to manipulate earnings (which is what Freddie Mac did in 2001 and 1002. Reduce problems of applying FAS 133 in hedge accounting where hedge accounting is now allowed only when the hedged item is maintained at historical cost. Provide a better snap shot of values and risks at each point in time. For example, banks now resist fair value accounting because they do not want to show how investment securities have dropped in value. 1-68 FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Disadvantages: Combines fact and fiction in the sense that unrealized gains and losses due to fair value adjustments are combined with “real” gains and losses from cash transactions. Many, if not most, of the unrealized gains and losses will never be realized in cash. These are transitory fluctuations that move up and down with transitory markets. For example, the value of a $1,000 fixed-rate bond moves up and down with interest rates when at expiration it will return the $1,000 no matter how interest rates fluctuated over the life of the bond. Sometimes difficult to value, especially OTC securities. Creates enormous swings in reported earnings and balance sheet values. Generally fair value is the estimated exit (liquidation) value of an asset or liability. For assets, this is often much less than the entry (acquisition) value for a variety of reasons such as higher transactions costs of entry value, installation costs (e.g., for machines), and different markets (e.g., paying dealer prices for acquisition and blue book for disposal). For example, suppose Company A purchases a computer for $2 million that it can only dispose of for $1 million a week after the purchase and installation. Fair value accounting requires expensing half of the computer in the first week even though the computer itself may be utilized for years to come. This violates the matching principle of matching expenses with revenues, which is one of the reasons why fair value proponents generally do not recommend fair value accounting for operating 1-69 assets. FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Disadvantages of Auditing FV The purpose of this International Standard on Auditing (ISA) is to establish standards and provide guidance on auditing fair value measurements and disclosures contained in financial statements. In particular, this ISA addresses audit considerations relating to the valuation, measurement, presentation and disclosure for material assets, liabilities and specific components of equity presented or disclosed at fair value in financial statements. Fair value measurements of assets, liabilities and components of equity may arise from both the initial recording of transactions and later changes in value. 1-70 FAS 159 effective in 2008 The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities Exclusions: Investments in consolidated entities Financial obligations for items such as pension benefits and other deferred compensation arrangements Income tax assets and liabilities Financial assets and liabilities recognized under leases as defined in Statement 13 Deposit liabilities, withdrawals on demand, of depository institutions Financial instruments that are, in whole or in part, a component of shareholder’s equity 1-71 IASB Discussion Paper IASB publishes Discussion Paper on fair value measurements November 30, 2006 with a May 1, 2007 Deadline. Expect new standard in 2008. The Board’s objectives in this project are to: (a) establish a single source of guidance for all fair value measurements required by IFRSs, (b) clarify the definition of fair value and related guidance in order to more clearly communicate the measurement objective, and (c) enhance disclosures about fair value 1-72 IASB FVO in Amended IAS 39 The European Commission has published Frequently Asked Questions providing the Commission's views on the following questions: Why did the Commission carve out the full fair value option in the original IAS 39 standard? Do prudential supervisors support IAS 39 FVO as published by the IASB? When will the Commission to adopt the amended standard for the IAS 39 FVO? Will companies be able to apply the amended standard for their 2005 financial statements? Does the amended standard for IAS 39 FVO meet the EU endorsement criteria? What about the relationship between the fair valuation of own liabilities under the amended IAS 39 FVO standard and under Article 42(a) of the Fourth Company Law Directive? Will the Commission now propose amending Article 42(a) of the Fourth Company Directive? 1-73 What about the remaining IAS 39 carve-out relating to certain FAS Standards Greatly Affected by FV FAS 32 --- Financial Instruments FAS 39 --- Derivative Financial Instruments FAS 41 --- Agriculture 1-74 IFRS Standards Greatly Affected by FV IFRS 2 --- Share-based payments (Categories of assets and liabilities to be measured at FV) IFRS 3 --- Business Combinations 1-75 IFRC 13 and Fair Value Question What's the status of international accounting for customer loyalty incentive awards such as airline miles, first class upgrades, hotel discounts, restaurant discounts, etc.? Answer There is a deferred revenue and liability recognition for future cost requirement. Allocation of the original sale is to be based upon estimated fair value of components of the sale. 1-76 IFRC 13 and Fair Value 1. The main issue addressed in the Interpretation is the recognition and measurement of obligations to provide customers with free or discounted goods or services if and when they choose to redeem loyalty award credits. 2. One approach used at present is to accrue an expense at the time of the sale, when the award credits are granted. The expense is based on the costs the entity expects to incur to supply the free or discounted goods or services. The rationale for this approach is that loyalty awards are incidental costs of securing the first sale, which should be recognised when that sale is made. 3. A second approach is to divide the proceeds of the first sale into two components—an amount that reflects the value of the goods or services delivered in the first sale and an amount that reflects the value of the loyalty award credits. Proceeds allocated to the first component are recognised as revenue at the time of the first sale. But proceeds allocated to the award credits are deferred as a liability until the entity fulfils its obligations in respect of the award credits, either by supplying the free or discounted goods or services itself when customers redeem the credits, or engaging (and paying) a 1-77 third party to do so. IFRC 13 and Fair Value 4. The practical difference between the two approaches is the measurement of the liability. The first approach measures the liability on the basis of expected costs; the second on the basis of selling prices. 5. The Interpretation requires entities to apply the second approach. The requirement reflects the IFRIC’s view that loyalty awards are separately identifiable goods or services for which customers are implicitly paying. The general standard on revenue recognition, IAS 18 Revenue, requires separately identifiable components of sales transactions to be accounted for separately if necessary to reflect the substance of the transactions. 1-78 A Formula to Remember for Later in the Day ForwardRate(t) = [1 + y(t)]t/[1 + y(t-1)]t-1 – 1 The ForwardRate(t) is the forward rate for time period t, y(t) is the multi-period yield that spans t periods, and y(t-1) is the yield for an investment of t-1 periods --- for example, if 6.5% is y(t) and 6.0% is y(t-1). Thus, ForwardRate(2), the forward LIBOR for year 2, is calculated as follows ForwardRate(2) = (1.065)2/(1.06) – 1 = 0.07 or 7.0% 1-79 Checklist for Valuing a Company Compilation of Financial Information: Financial statements and federal income tax returns for the last three to five years should be reviewed and the information "adjusted" and/or "weighted" to more properly reflect future operations: Audited vs. unaudited statements to reflect accurate levels of inventories and receivables. Determine latest work-in-process value -- particularly where production costs have been expensed rather than capitalized. Delete extraordinary or non-recurring revenues or expenses. 1-80 Checklist for Valuing a Company Adjust for differences in cash vs. accrual methods of reporting income. Add back any "excess" owner/employee cash compensation and fringe benefits.\ Determine net fair market value for tangible assets (eg., book value vs. liquidation value vs. replacement value of equipment, obsolete or slow-moving inventory, supplier return privileges, credits, etc.). Determine undisclosed and/or disputed liabilities (eg., unfunded past service costs or multi-employer obligations for pension plans, deferred compensation plans; incentive bonuses; stock options; potential contract or tort claims; potential unfunded sales income or payroll tax obligations). 1-81 Checklist for Valuing a Company Valuation: There is usually no "magic" correct value but rather an appropriate range of values dependent upon the "fit" of buyer and seller and the realism of the assumptions utilized in the valuation methodology. Also, consideration should be given to internal expressions of valuation (eg., buy-sell agreements, insurance arrangements, and deferred compensation and noncompetition agreements). 1-82 Checklist for Valuing a Company Obtain Outside Appraisal: A qualified business appraiser can offer insights as to comparable sales or to appropriate valuation calculation assumptions (eg., industry risks and capitalization rates, interest rates, etc.) as well as helpful analyses of alternative valuation method approaches (eg., discounted cash flow analysis vs. liquidation value vs. tangible/intangible asset valuation as set forth in Revenue Ruling 59-60 as modified/amplified by Revenue Rulings 65-192, 65-193, 68-609, 71-287, 80-213 and 83120; etc.). 1-83 Checklist for Valuing a Company Strategic and/or Value Added Components: Synergies Supplementary product lines Operating economies and/or vertical integration opportunities New supply or distribution avenues Limination of price and customer competition R&D, Patents, Copyrights Skilled and loyal work force No huge owner dependencies 1-84 Checklist for Valuing a Company Reductions or Add-Ons for Contingent Events: Sometimes, it is appropriate to reduce or supplement a calculated value for future possible contingencies (good and bad) -- eg., labor union problems, plan closure obligations, multi-employer pension plan obligations, unfunded past service pension costs, product liability exposures, tax exposures, short-term lease rights, uncertain supply or sales commitments or credit lines, patent expirations or other intellectual property uncertainties and/or exposures, as well as the prospect of greater profitability from new customers, lines, technology or endeavors which have not yet been reflected in historical financial results. 1-85 Free Online Real Estate Appraisals Local Links --- ..\..\..\Tidbits\2007\tidbits070809.htm Eppraisal.com --- http://eppraisal.com/ Realestateabc.com --- http://realestateabc.com/ Homegain.com --- http://homegain.com/ Zillow --- http://www.zillow.com/ 1-86 Banking Concerns BIS Paper 109 --- Online Click Here Offline Click Here 1-87 1-88 The End 1-89