Assessment3

advertisement

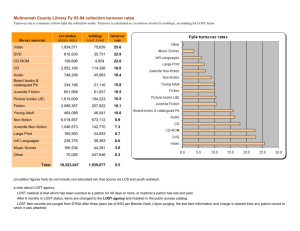

Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 1 Assessment 3 – Draft Journal Group & Organization Management Journal Author guideline Your submission (including references) conforms to APA format as outlined in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (5th edition). General APA Guidelines Your essay should be typed, double-spaced on standard-sized paper (8.5" x 11") with 1" margins on all sides. You should use 10-12 pt. Times New Roman font or a similar font. Include a page header in the upper right-hand of every page. To create a page header, type the first 2-3 words of the title of the paper, insert five spaces, then give the page number. All text, including references, is double-spaced in 12-pitch or larger font with margins of one inch or more. Your title page includes complete contact information for all authors, including mailing addresses, e-mail addresses, phone and fax numbers. Your abstract is 120 words or less. Your submission contains few and only necessary endnotes. There is nothing in your GOM NO-AUTHOR file that identifies the authors. The text of your submission, including abstract, body of the paper, and references (but not including title page, tables, and figures), is no longer than 35 pages total. Any prior publication of the data featured in the manuscript is explicitly acknowledged either in the manuscript or in the transmittal letter to the editor. Any forthcoming or "in press" articles which use the data should be forwarded to the editor with the submission. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction Running Head: Moderesting factor to job satisfaction Moderesting factor to job satisfaction; Why satisfied banking employees leave the organization? Warayu Thienpramuk University of South Australia 2 Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 3 Abstract With regards to determinants of employee turnover, many past studies have found that job dissatisfactions are sufficient to determine the turnover intention (Dole, & Schroeder, 2001). However, there are other researchers who have argued that job dissatisfaction should not be sufficiently used as determinant of turnover intention, there should be the possible impact of other variables (Aranya et al., 1982; Aranya and Ferris, 1984; Omundson et al., 1997). While previous researches typically associate with decreased job satisfaction and increased turnover, this present research suggests that intervening variables, such as job mobility, influence employee intentions to turnover. This finding represents one of dimensions in this area of research. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 4 Introduction The coming of the 21st century brings with it challenges for businesses that want to enjoy a competitive edge over their rivals. This would need to include having a work force that is stable and reliable. An increasing amount of research suggests implementation of high performance work practices to reduce voluntary turnover. These high performance work systems are an approach to an organization’s drive to improve its production, service delivery, and quality to its customers (Huselid, 1995). They may include employee recruitment and selection procedures, remuneration incentives, performance appraisal systems such as 360-degree feedback, and training, education and development that improve the knowledge, skills, and abilities of the employee. These are aimed at increasing the employee’s motivation and effectively enhancing the retention of high performers within the organization (Barrick & Zimmerman, 2005; Huselid, 1995). Huselid (1995) has found direct evidence that these human resource management practices have a direct impact by lowering employee turnover, raising productivity, and improving financial performance. This study has shown the significance of the research problem in banking industry of Thailand by following these reasons; Firstly, For Thailand, the national development plan guidelines could be seen in the National Economic and Social Development plan, which have been implemented since 1961 as the first plan. Until now it has been about 46 years, and currently we are in the tenth version of the National economic and Social Development plan. It has been heavily focused on the economic development and the Thai government had tried to gear the nation towards the so-called new industrialized country or “NIC” (Office of National Economic and Social Development Board, 2007). Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 5 In order to achieve the nation plan, every organization and industry are the important key. The banking industry plays a central role in economy as a tools for monetary policy. The economy would be unable to function without the many forms of bank services. Banks extend loans to businesses and private persons, making it possible for them to invest. Furthermore, they handle payments and securities transactions, manage savings, and advise and guide enterprises when they go public (Clark Medal, 1977). Secondly, there are evidences from Thai Bank Association show that the turnover rates of Thai bank staff are increasing every year without explained reason. Since year 2006 -2007, the average turnover rates are 4.6% and 5.2% respectively (compare to another industry in financial sector, average turnover rate only 3.5% in insurance industry) and the research department of Thai Bank Association predicts that it will be higher this year 2008. Although there are relevant studies on employee turnover in Thailand but I have not found the research focus in Banking Industry in Thailand. Thirdly, in the context of the Free trade agreement (FTA), for the local banks, there are evidences that foreseen implications on the costs side can be summarized by reduced profitability due to higher competition (Saad Al Jundi, 2005). Lefkowitz (1967:8) has indicated that turnover has generated high cost to the industry. Some of the more important costs include recruitment costs (advertising), the personnel department’s interviewing time, the costs of physical examinations, orientation and training cost, non-productive on-the-job training time (for the new employee, his supervisor, and any older employee to whom training may be delegated), payroll processing costs, personnel staff processing costs and lower production or additional overtime for other workers filling in until a replacement is found. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 6 As a result of major changes in the banking industry and the increasing financial and competitive pressures, many banking institutions have become keenly interested in identifying the causes of staff turnover. Identification and management of staff turnover clearly can improve the financial well being and long-term survival of banking institutions in an increasingly competitive market. The present research has four goals. First, we review the literature on the job satisfaction and intent to turnover relationship. Second, we examine the moderating factors influence on job satisfaction and intent to turnover relationship. Third, we empirically test our hypothesized relationships between these variables. Finally, we discuss the implications of our model and our results. Theoretical background, review of literature, and hypotheses development Decreasing employee turnover as the key to create an organization’s competitive advantage In recent decades, academic literature has argued that the human resources (HR) of the firm are potentially the sole source of sustainable competitive advantage for organizations (Kochan and Dyer, 1993; Pfeffer, 1994). These works have drawn on the resource-based view of the firm and have argued that few of the more traditional sources of sustainable competitive advantage create value in a manner that is rare, non-imitable, and non-substituable (Ferris et al., 1999). Following the resource-based view of the firm theory it has been argued that more attention must be paid to the resources required to execute strategies (Barney, 1991; Teece et al., 1997). One such key resource is the human capital of an organization – its workforce. Following Lee and Miller (1999), a dedicated and talented workforce may serve as a valuable, scarce, non imitable resource that can help firms execute an appropriate Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 7 positioning strategy. Thus, Organizational HR practices have received increased attention of late for their effects on an important outcome variable, turnover. Staff retention has become the leading challenge facing many human resources departments. The term “turnover” has been defined by many scholars such as Price (1975) who defined turnover as “the degree of movement across the membership boundary of an organization. These movements are individuals either coming into the organization or leaving the organization”. Mobley (1982) defined labor turnover as “the cessation of membership in an organization by an individual who received monetary compensation from the organization.” He distinguished between voluntary separation (employee-initiated) and involuntary separation (organization-initiated, plus death and mandatory retirement). He further mentioned that “turnover is not all bad, and is important to organizations, individuals and society” (Mobley, 1982). Tracey (1991) defined labor turnover as “the changes in the composition of the work force due to termination. The importance of turnover lies in its effect on employee morale, recruitment and hiring and firing cost”. Lefkowitz (1967) defined labor turnover as “potentially successful employees leaving the company, whatever the cause or circumstances”. Mobley (1982) focuses on consequences of turnover from different perspectives: organizational, individual and social. In term of organizational consequences, Mobley (1982) purports that cost carried by organizational include 1) acquisition cost such as recruitment, selection and placement, 2) learning costs, including training cost and lost of the trainer’s time, and 3) separation cost, including direct costs of separation pay and indirect costs from loss of efficiency prior to separation and the cost of the vacant position during the search time. Mobley (1982) Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 8 further stated that turnover negatively affects worker cohesiveness, disrupts performance, disrupts social and communication patterns, lowers morale of others, and forces implementation of different control strategies. Mobley (1982), however, indicates negative consequences for individuals, such as disruption of social and communication pattern, loss of functionally valued coworkers, decreased satisfaction, and increased workload during and immediately after searches for replacements and decreased cohesion and commitment. In term of social consequence, some possible negative consequences explained by Mobley (1982) are plant costs due to lack of employees and the inability to attract and retain a competent work force. He further revealed that in the early 1970’s, high levels of turnover increased the cost of production and even resulted in idle productive capacity due to a lack of trained operators in the industry. In literature, turnover intention has been identified as the immediate precursor for turnover behaviour (Mobley, Horner & Hollingsworth, 1978; Tett & Meyer, 1993). It has been recognised that the identification of variables associated with turnover intentions is considered an effective strategy in reducing actual turnover levels (Maertz & Campion, 1998). Extensive empirical research has been carried out on the linking of HR practices and employee turnover, especially at the organizational level (Shaw et al., 1998; Delery et al., 2000). Boselie et al. (2005) were able to identify 27 empirical articles on HR and turnover in the time period 1994-2003. Retaining staff is usually a far better investment than the cost of recruiting replacements (Mitchell et al., 2001; Farrel, 2001). For example, turnover rate moderates the curvilinear relationship between social capital losses and performance (Shaw et al., 2005). However, little explanation has been offered for how HR practices influence individual turnover decisions (Guest, 1999; Allen et al., 2003). Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 9 Turnover intentions Turnover intentions refer to an individual's estimated probability that they will leave an organisation at some point in the near future. Turnover intentions are identified as the immediate precursor to turnover behaviour (Mobley, Horner, & Hollingsworth, 1978; Tett & Meyer, 1993). Employees may exit an organisation either voluntarily or involuntarily. For the purpose of this research, ‘turnover intention’ is defined as an employees decision to leave an organisation voluntarily (Dougherty, Bluedorn & Keon, 1985; Mobley, 1977). Employees leave for a number of reasons, some to escape negative work environments, some are more in alignment with their career goals, and some to pursue opportunities that are more financially attractive. Involuntary turnover is usually employer initiated, where the organisation wishes to terminate the relationship due to incompatibilities in matching its requirements. Involuntary turnover can also include death, mandatory retirements, and ill health (Mobley, 1977). In literature, turnover intention has been identified as the immediate precursor for turnover behaviour (Mobley, Horner & Hollingsworth, 1978; Tett & Meyer, 1993). It has been recognised that the identification of variables associated with turnover intentions is considered an effective strategy in reducing actual turnover levels (Maertz & Campion, 1998). Job satisfaction and Turnover intention relationship Many past studies have found that job dissatisfactions are sufficient to determine the turnover intention (Dole & Schroeder, 2001). The relationship of job satisfaction with turnover intentions is well documented (Abdel-Halim, 1981; Choo, 1986, Rasch and Harrell, 1990). Research investigating this relationship was designed to measure the correlation between job satisfaction and turnover intentions and Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 10 initially found an inverse association between job satisfaction and turnover intentions. The empirical findings and the advice to organizations are clear. Increase job satisfaction to decrease turnover intention, with the converse of those relationships being true, as well (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Verquer et al., 2003). Thus, we make the following hypothese. H1: Job satisfaction and intent to turnover are negatively related, such that participants reporting high levels of job satisfaction will also report low levels of intent to turnover. With regards to the relationship between Job satisfaction and Turnover intention, some researchers have supported the strong relationship between the two constructs (Spector, 1997) that job satisfaction is sufficient to determine turnover intention, while some others still question this relationship (Jawahar and Pegah Hemmasi, 2006). Moreover, in the recent studies, there are other researchers who have argued that job satisfaction should not be sufficiently used as determinant of turnover intention, there should be the possible impact of other variables (Aranya et al., 1982; Aranya and Ferris, 1984; Omundson et al., 1997). Lee and Mitchell (1994) theorized that job dissatisfaction could indeed result in turnover but that it was more likely that other factors would act as moderators to the turnover intention. Moreover, recent empirical studies have shown a weak relationship between the two constructs (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Verquer et al., 2003). Indeed, the weak relationship suggests that more employees remain in organization despite the lack of job satisfaction. These empirical finding lead to question why unsatisfied employee still remain in organization and why satisfied employees leave the organization, which Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 11 is the exact purpose of the present research. These issues, we feel, can be attributed to the lack of a clear theoretical framework that explains how job satisfaction triggers turnover intention. Job satisfaction – job mobility – intent to turnover relationship Unfolding model of voluntary turnover Lee and Mitchell (1994) proposed a novel job search theory called the unfolding model of voluntary turnover (UMVT). Historically, turnover researchers viewed two variables as key to understanding why employees voluntarily leave organizations: job satisfaction and perceived job alternatives (Hulin et al., 1985). Mobley (1977) proposed that job dissatisfaction led to a linear series of cognitive evaluations, starting with initial thoughts of leaving the job followed by the comparison between the current job and possible job alternatives, and ending with intentions to leave the organization. Lee and Mitchell (1994) argued that while this linear decision-making process intuitively appeals to many researchers, the equivocal empirical support for these types of models suggests that voluntary turnover was more complex than previously thought. However, the UMVT does not nullify the traditional models of turnover as much as it incorporates and expands these models. Lee et al. (1996) summarize that “factors other than affect can initiate the turnover process, employees may or may not compare a current job with alternatives, and a compatibility judgment . . . may be used”. The UMVT is theoretically grounded in Beach’s (1990) image theory. Image theory describes the process of how individuals process information during decisionmaking. Beach argues that individuals seldom have the cognitive resources to systematically evaluate all incoming information, so individuals instead simply and Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 12 quickly compare incoming information to more enduring heuristic-type decisionmaking alternatives. Beach considered this comparative process a default or status quo decision-making process. Lee and Mitchell (1994) reasoned that expected or unexpected dramatic events, or shocks, to an individual’s status quo decision-making process would lead to a series of possible job search paths. Image theory asserts that these existing status quo decision-making processes are context bound. That is, individuals possess mental images that represent specific domains of their lives (e.g. work, family, friends, etc.) that act as behavioral guides for specific environments (Mitchell and Beach, 1990). In decision-making situations, where individuals will scan the environment for information, these idiosyncratic images, which are akin to heuristics, are the default behavioral guides to which all other alternative information is compared (Beach, 1990). The key to understanding the UMVT centers on the fallout from experiencing a shock. In essence, a shock can cause individuals to reassess existing idiosyncratic images, which in some instances will cause image violation (Lee and Mitchell, 1994). That is, in some cases, individuals can receive information that shocks the decision-making process into abandoning existing images for newly created images. Lee and Mitchell (1994) assert that job search is typically a function of shocks, which cause individuals to scrap status quo reasoning (i.e. remaining with the current organization) in lieu of alternative decision-making processes. Lee and Mitchell (1994) identified four alternative decision-making paths by which individuals can travel in the job search process. Path 1 begins with a shock, which causes individuals to scan previous experiences for similarities to the present shock. Should the present shock match a past decision-making event and should the outcome of that previous experience be judged in retrospect as being the correct Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 13 decision to make, individuals will simply follow the same decision-making process that was successful in the past event. Path 2 describes how a shock leads individuals to reassess their commitment to the organization, and the shocks that trigger the turnover decision-making process cause individuals to assess fit with the organization, even if no other job alternatives are present. The shocks resulting in path 3 cause individuals to assess whether or not their commitment could be associated with a different organization. The decision-making process in path 3 requires explicit comparisons between an individual’s current organization and at least one possible alternative. In path 3, the shock induced assessment and directly leads to increases in job dissatisfaction, which then results in the scanning for possible job alternatives. If the individual believes that a job alternative will not provide better than the current job, that individual will remain with their current organization (e.g. stay to avoid image violation). On the other hand, if the individuals believe that they will be achieved by working for another organization that individuals will likely decide to leave the current organization. Finally, path 4 describes how individuals simply change over time and reassess commitment to an organization. That is, no shock occurs to stimulate job search; however, affective responses to daily organizational life (e.g. commitment and job satisfaction) over time can cause individuals to turnover even without suitable job alternatives. Path 4 most closely resembles the traditionally sequential models of turnover, with job dissatisfaction leading to search of job alternatives and subsequent intention to turnover. In the present research, we assert that the UMVT, specifically paths 2, 3 and 4, directly relate to this study and explain how and why the moderate factors will lead some to leave the organization while others will remain. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 14 Consistent with both traditional sequential models of turnover (e.g. Mobley, 1977) and the unfolding model of voluntary turnover (UMVT), Wheeler et al. (2005) include perceived job mobility, which is defined as an individual’s perception of available alternative job opportunities, as a key moderating variable between causes of the decision to turnover. An employee experience job dissatisfaction, the likelihood of an employee leaving the organization depends on that employee’s perceptions of available job alternatives. In the UMVT, job dissatisfaction causes individuals to scan the environment for possible job alternatives. If no suitable job alternatives exist, the individual will remain with the organization. Thus, we expect perceived job mobility to moderate the relationship between job satisfaction and intent to turnover. Moreover, we expect this interaction to explain how high levels of job dissatisfaction coupled with low perceptions of job mobility lead to reduced intent to turnover compared with high levels of both job dissatisfaction and job mobility. Thus we make the following hypothesis. H2. Participant perceived job mobility moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and intent to turnover, such that participants who perceive high levels of job mobility but report low levels of job satisfaction will also report higher levels of intent to turnover compared to participants who perceive low job mobility and low job satisfaction. Job Mobility H2 (-) Overall Job Satisfaction H1 (-) Turnover Intension Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 15 Method The population and sample size The unit of population analysis in this study is the individual staffs who work fulltime in every Thai bank during the year 2008. Questionnaires will be administered to that staffs who has been working with the institution for at least a period of 12 months. The staff must have been working in the organization long enough to able to specify, recognize and get acquainted with the working environment. For this research, I will determine number of sample size based on the equation of Taro Yamane’s (1967) which is commonly used by many researchers (e.g. Dane, 1997; Christo, 1994; Sarah, 1994) as shown below. n = N / [1 + N(e)2] n = Sample size N = Total population e = Sampling error (0.05) N= Population: Thai Bank staffs The Thai Bank Association has presented that presently there are approximately 80,000 Full Time - Thai bank staffs (exclude the manager and executive level). Calculation are shown as below: Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction N = 16 80,000 [1 + 80,000(0.05)2] = 80,000 201 By Calculating from Yamane’s equation: Total Sample size will be: n = 398.01 n >= 399 Sample and data collection A total of 452 fulltime employed participants completed a HTML-based web survey however we excluded data collected from 34 of the participants due to incomplete responses. Due to in the consent form and guideline in first page of questionnaire, we stated that the participants may withdraw from the research project at any stage and that this will not affect in the future. Therefore, a total of 418 fulltime employed participants completed the survey with their own intention. Moreover, a HTML-based web survey gives the participants an opportunity to read questions and answer them carefully. Since the questionnaire will be sent to Thai bank staff. The Thai bank employee association was the main distribution channel to send the e-mail directly to each staff through intranet system. The distribution of questionnaire through this process received a good response because it comes from government agency’s request. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 17 Pre-test was conducted on 20 sample respondents in order to help the questionnaire modification and to assess the validity and applicability of the measures. Measures As mentioned, all participants completed our survey instrument on-line. For the completion of the web-based survey, all attitudinal and behavioral items (unless otherwise noted) were anchored on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree.” Midpoints (values of 4) were anchored with the word “neutral.” The items in each scale were summed and then averaged to arrive at an overall value for the scale. Higher scores represent higher levels of each of the constructs. Job satisfaction. We measured job satisfaction using questions developed by Cammann et al. (1979). A sample item is “All in all, I am satisfied with my job.” Perceived job mobility. We measured perceived job mobility questions developed by McAllister (1995). A sample item is “If I were to quit my job, I could find another job that is just as good.” Intent to turnover. We measured participant intent to turnover using questions developed by Seashore et al.’s (1982). A sample item is “I will probably look for a new job in the next year.” Results We are during data analysis process. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 18 References Abdel-Halim, A. (1981), Effects of role stress-job design-technology interaction on employee work satisfaction, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 260-73. Aranya, N. and Ferris, K.R. (1984), A reexamination of accountants' organizational professional conflict, The Accounting Review, Vol. 59 No. 1, pp. 1-15. Aranya, E.I., Lachman, R. and Amernic, J. (1982), Accountants' job satisfaction: a path analysis, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 201-15. Aiken, L. and West, S. (1991), Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. Baron, R.M. and Kenny, D.A. (1986), The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 51, pp. 1173-82. Cable, D.M. and Judge, T.A. (1996), Person-organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 67 No. 3, pp. 294-311. Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D. and Klesh, J. (1979), The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Ferris, G.R., Treadway, D.C., Kolodinsky, R.W., et al. (2005), Development and validation of the political skill inventory, Journal of Management, Vol. 31, pp. 126-52. Hellman, C.M. (1997), Job satisfaction and intent to leave, Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 137, pp. 677-89. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 19 Hulin, C.L., Roznowski, M. and Hachiya, D. (1985), Alternative opportunities and withdrawal decisions: empirical and theoretical discrepancies and an integration, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 97, pp. 233-50. Kristof-Brown, A.L., Zimmerman, R.D. and Johnson, E.C. (2005), Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 58, pp. 281-342. Lee, T.W. and Mitchell, T.R. (1994), An alternative approach: the unfolding model of voluntary turnover, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, pp. 51-89. Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.M., Wise, L. and Fireman, S. (1996), An unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, pp. 536. Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.R., Holtom, B.C., McDaniel, L.S. and Hill, J.W. (1999), The unfolding model of voluntary turnover: a replication and extension, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 450-62. Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.R., Sablynski, C.J., Burton, J.P. and Holtom, B.C. (2004), The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, pp. 711-22. Mitchell, T.R., Holtom, B.C., Lee, T.W., Sablynski, C.J. and Erez, M. (2001), Why people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, pp. 1102-21. Mobley, W.H. (1977), Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 62, pp. 237-40. Moderesting factor toJob satisfaction 20 Spector, P.E. (2006), Method variance in organizational research: truth or urban legend?, Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 9, pp. 221-32. Spell, C.S. and Blum, T.C. (2005), Adoption of workplace substance abuse prevention programs: strategic choice and institutional perspectives, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, pp. 1125-42. Tett, R.P. and Meyer, J.P. (1993), Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 46, pp. 259-93. Trevor, C.O. (2001), Interactions among actual ease-of-movement determinants and job satisfaction in the prediction of voluntary turnover, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, pp. 621-38. Wheeler, A.R., Buckley, M.R., Halbesleben, J.R., Brouer, R.L. and Ferris, G.R. (2005), The elusive criterion of fit revisited: toward an integrative theory of multidimensional fit, in Martocchio, J. (Ed.), Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management, Vol. 24, Elsevier/JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 265304.