Competitive-Advantage in a changing world

advertisement

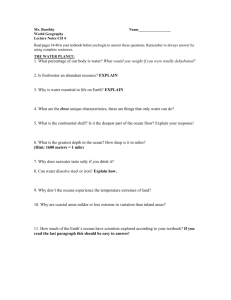

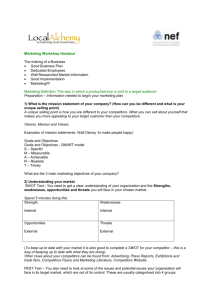

Competitive Advantage in a Changing World. On the basis of Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Pyle, S. (2011). Exploring strategy: text & cases. 9 th edition. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall and Ms Claire’s Devlin: “Analysing strategic capabilities and competitive advantage” lecture of Strategic managemnet module series, Dublin Business School 2013. Analysing Organisational Capability The case for making the resources and capabilities of the firm the foundation for its long-term strategy rests upon two premises: first, internal resources and capabilities provide the basic direction for a firm’s strategy; second, resources and capabilities are the primary source of profit for the firm.” – Robert Grant (1991). Why analyse company capabilities? To determine if organisational resources and capabilities match Critical Success factors. Resources are the basis of sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). It is the basis for control and evaluation. Content of the analysis Tangible resources - Physical assets - Financial strength - Human resources – Intangible resources - Knowledge base - Intellectual property - Relationships - Perceptions (incl. Brands) A distinction needs to be made between strategic capabilities that are at a threshold level and those that might help the organisation achieve competitive advantage and superior performance. Above table summarised these distinctions. Threshold capabilities are those needed for an organization to meet the necessary requirements compete in a given market and achieve parity with competitors in that market. Without such capabilities the organisation could not survive over time. Indeed many start-up business find this to be a case. They simply do not have or cannot obtain the resources or competences needed to compete with established competitors. Identifying threshold requirements is, however, also important for established businesses. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century BP faced declining oil output in countries such as the US, the UK and Russia. BP’s board regarded securing new sources of supply as major challenge. In 2008/9 some high profile financial institution went bankrupt or were bailed out by huge government funding because they did not have the financial resources to meet their debts s recessionary pressures grew. Here could also be changing threshold resources required to meet minimum customer requirements: for example, the increasing demands by modern multiple retailers of their suppliers mean that those suppliers have to possess a quite sophisticated IT infrastructure simply to stand a chance of meeting retailer requirements. Or they could be the threshold competences required to deploy resources o as to meet customers’ requirements to support particular strategies. Retailers do not simply expect suppliers to have the required IT infrastructure, but to be able to use it effectively so as to guarantee the required level of service. Identifying and managing threshold capabilities raises two significant challenges: 1/ Threshold levels of capability will change s critical success factor change or through the activities of competitors and new entrants. To continue the example, suppliers to major retailers did not require the same level of IT and logistics support a decade ago. But the retailers’ drive to reduce costs, improve efficiency and ensure availability of merchandise to their customers means that their expectations of their suppliers have increased markedly in that time to continue to do so. So there is a need for those supplier continuously to review and improve their logistics resources and competences base just to stay in business. 2/ Trade-offs may need to be made to achieve the threshold capability required for different customers. For example, businesses have found difficult to compete in market segments that require large quantities of standards products as well as market segments that require addedvalue specialist products. Typically, the first requires high- capacity, fast- throughput plant, standardised highly efficient systems and a low-cost labour force as; the second a skilled labour force, flexible plant and a more innovative capacity. The danger is that an organisation fails to achieve the threshold capabilities required for either segment. While threshold capabilities are important, they do not themselves create competitive advantage or the basis of superior performance. These are depend on an organisation having distinctive or unique capabilities that are o value to customers and which competitors find difficult it imitate. This could be because the organisation has distinctive resources that critically underpin competitive advantage and hat others cannot imitate or obtain a longestablished brand, for example. Or it could be that an organisation achieves competitive advantage because it has distinctive competences – ways of doing things that are unique to that organisation and effectively utilised so as to be valuable to customers and difficult for competitors to obtain or imitate. Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahaland argue that the distinctive competences that are especially important are likely to be: “A bundle of consistent skills and technologies rather than simple, discrete skill or technology”. They use the term core competitiveness to emphasize the linked set of skills, activates and resources that, together, deliver customer value, differentiate a business from its competitors and, potentially, can be extended ad developed. For example s markets change or new opportunities arise. Here are, then, also similarities here to Teece’s conceptualisation of dynamic capabilities. Bringing these concepts together, a suppliers that achieves competitive advantage in a retail market might have done so on the basis of a distinctive resources such as powerful brand, but also may distinctive competences such as the building of excellent relations with retailers. However, it is likely that what will be most difficult for competitors to match ad will therefore be basis of competitive advantage will be multiple and linked ways of providing products, high levels of service and building relationships – its core competence. Core Competencies The concept of core competencies (cc’s) helps explain why some firms consistently generate mare successful products than others. DEFINICION: “Core competencies are the collective learning in the organisation, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies.” (Prahaland and Hamel, 1990). Key features include: Cc’s provide potential a wide variety of markets Cc’s make a significant contribution to perceived customer benefits from final product Cc’s should be hard for competitors to imitate. Problems with CC Concept - Identifying cc’s is problematic. Difficult to know in advance what competencies to focus strategic investment on. Durability of competence is susceptible to technological discontinuities. Few organisational competencies actually meet Prahaland and Hamel’s 3 test. What is a competitive advantage? “When two or more firm operate within the same market, one firm possesses a competitive advantage over its rivals when it earns (or has the potential) to earn a persistently high rate of profit” (Grant, 2002 p. 227). According to Lynch (2002) CA derives from doing things: - Better; Faster; Cheaper. Generic Competitive Advantage “Competitive advantage is anything which give the organisation and advantage over the rivals in the products it sells or he services it offers.” Cost leadership – the lowest cost producer in the industry. Differentiation – products or services that is believed to be unique in the industry as a whole. How do you gain CA? Porter’s generic strategies Cost leadership – organising value adding activities so as to be the lowest cost producer in an industry. Differentiation – persuading customers that a product is superior to those offered by competitors. Focus – aimed at a segment of the market. Cost leadership – cost reduction greater than price reduction; Differentiation – price increase greater than cost increase Out-Performer – superior value at reduced cots Lower cost of production can - Defend against powerful buyers driving down sales prices; Buffer against supplier driving cost up; Build entry barrier; Weaken threats of substitution; Free capital to support marketing strategies for expansion of market share. Differentiation can be via: - Quality (Harrods label); Features (Nintendo games); Style & design (Jaguar cars); Brand (Mars in chocolate, drinks, ice cream); Customer service (Singapore Airline); Technology and performance (Apple Computers) - Packaging (After Eight Mints); Uniqueness (Coca Cola). Focus can be narrowed towards: - End user (McDonalds for Kids); Customer features (large size clothing); Geography (city, regional or country focus); Product line (Tie Rack); Quality- price mechanism (Rolls Royce cars); Service specialism (Singapore Airlines). Value & Competition Issue Values perceived by the market is the basic issue in the differentiation strategy; Perceived Value is the basic link between the creation of value activities and the establishing of competitive advantages. The value activities which consistently create the most value within the organisation is thus the organisation’s core competencies. The Strategy Clock The strategy clock provides another way of approaching the generic strategies. The strategy clock has two distinctive features. First it is more marked-focused than the generic strategies, being focused on prices to customers rather than costs to the organisation. Second, the circular design of the clock allows for more continuous choices than Michael Porter’s sharp contrast between cost-leader and differentiation: there is a full range of incremental be made between the 7 o’clock position at the bottom of the low-price strategy and the 2 o’clock position at the differentiation strategy. Originations often travel around the clock, as they adjust their pricing and benefits over time. The strategy Clock illustrates the various competitive strategy option based on the perceived added value and the price. Note that these considerations are based on the concept of the price, not on cost. And therefore should not be confused with other generic strategy of cost leadership. Position 1: Low price, low added value: Likely to be a segment specific. Position 2: Low price: Risk of price war, need to be a cost leader. Position 3: Hybrid: Require low cost base but can avoid price war. Position 4: Differentiation: Without premium price but benefit from market share. Position 5: Focused differentiation: Perceived value to particular segment thus warrant price premium. Position 6: High price, standard value: Non-competitive. Position 7: High price, low value: Only feasible (wykonalne) if monopoly. Position 8: Low value, standard price: Non-competitive. Summary of the strategic clock model Routes 1 and 2 are price-based strategies; Route 3 is a hybrid strategy; Routes 4 and 5 are differentiation strategies: Routes 6, 7 and 8 are strategies destined for ultimate failure. Where does CA come from? Superior quality Superior efficiency Superior customer responsiveness Superior innovation Strategic relationships. Value Chain Analysis The value chain describes the categories of activities within an organisation which, tougher, create a product or service. Most organisations are also part of wider value network, the set of inter-organisational links and relationships that are necessary to create a product or service. If organisations are to achieve competitive advantage by delivering value to customers, managers need to understand which activates their organisation undertakes are especially important in creating that value and which are not. It can, hen be used to model the value system of an organisation. The important point is that the concept of the value chain invites the strategist to think of an organisation in terms of sets activates. In analysing activates, be careful to distinguish direct activates from indirect activates; Direct activates are activates that add value to inputs Indirect activates are activates which enable direct activates to be performed (e.g. Maintenance, administration, etc. Problems with VC Analysis Disaggregating an organisation into meaningful “activities” is problematic; The split between primary and secondary activities is increasingly obsolete is more “support” activities are decentralised now, e.g. technology improvement, HRM, etc.; The trend towards outsourcing means many activities are no longer performed in-house; Building in links between activities to make them hard to imitate. Financial analysis and strategy Usual to produce five record for trend analysis; Balance sheet for asset use, liquidity/ gearing and cash-flow (financial strength); P&L a/c for ratios, operating profits, expenses and EPS (past performance); Shareholder Value Approach - focuses on future long term value creation (overcomes many problems of EPS, e.g. includes risk, investment needs, cost of capital, inflation, and time value of money); Financial health affects ability to defend, available options and timing of actions. Use of SWOT It can be helpful to summarise the key issues arising from an analysis of the business environment and the capabilities of an organisation to gain an overall pictures of its strategic position. Basis of (SWOT): Identify strategy to exploit strength; Identify strategy to strength weakness; Matching opportunity to strength; Eliminating or avoid weakness and threats. Strengths and Weaknesses - Marketing (e.g. advertising, new product launch, PR.); Products (e.g. features, profits, demands); Distribution (e.g. efficiency, location factors); R&D (e.g. potentials and abilities); Finance (e.g. funding, cash flow, returns); Fixed assets (e.g. plants, machinery, age, capacity); HR (e.g. management, staff, relationships, culture); Organisation (e.g. structure, leadership style); Resourcing (e.g. availability, relationship with suppliers). Opportunities - What are they? What are their potentials? What are the likelihood of happening? Can the organisation exploit them? Comparative capability to exploit vis –a vis competitors. Threats - What are they? What are the likely impact on the organisation? What are the likelihood of happening? Can the organisation overcome? Comparative capability to overcome vis –a vis competitors. Benchmarking Benchmarking is used as a means of understanding how an organisation compares with others – typically competitors. Many benchmarking exercises focus on outputs such as standards of product or service, but others do attempt to take account of organisational capabilities. Historical benchmarking – comparing current performance with past performance; Competitor benchmarking – relative performance and strength of direct competitors using information from customers or suppliers interview and published data from other sources; Process benchmarking – exchange and sharing of data between companies with similar administrative and manufacturing processes to form a standard (best in class). Gap analysis Analysis of gaps is a very effective technique for guiding the planning team in looking for corporate strategies to achieve targeted levels of corporate performance. This kind of analysis is a very simple procedure. So often the simplest tools are the most useful! However certain other key things must be in place to be able to take advantage of this tool. Requirements for effective gap analysis The things are required Clearly agreed indicators of overall corporate performance; it is highly desirable that that the indicator of overall corporate performance should be traceable through a range of business performance metrics, in the form of simple cause and effect relationships, sometimes called a value driver tree. Sound data feeding the results measured by the key performance indicators (KPI) used in the organization, including data on the performance of the organization for the past few years. An agreed time span for the strategic planning exercise for comparing forecast performance under different assumptions. These various sets of assumptions may be trialled in a process of scenario planning. Before performing an analysis the strategic planning team needs to undertake target setting. The targets for desired future performance of the organization need to be set using the corporate performance indicator mentioned above. Target setting should be done with possible risks of corporate collapse in mind. The availability of forecasting techniques, for the strategic planning team to use in the business forecasting of likely corporate results under various scenarios. This may sometimes warrant the employment of business forecasting software. With all of these things in place then the analysis consists of addressing two questions, and measuring the difference between the two answers. Where do we intended to be in X years, where ‘X’ is the planning horizon, say usually at least 3 years for corporate strategic planning? This is the target setting question. Where are we likely to be in level of corporate results, in X years if we do not do anything different to what we currently are doing? This is the business forecasting question. The difference between the two sets of results is the ‘gap’ to be closed by changes to strategies. A simple version of gap analysis is depicted in this diagram- The challenge for the strategic planning team is to close the gap. The key process for finding what is required to do this is called the SWOT Analysis. Blue Ocean Thinking Blue Ocean Strategy is a business strategy book first published in 2005 and written by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne of The Blue Ocean Strategy Institute at INSEAD. The book illustrates what the authors believe is the best organizational strategy to generate growth and profits. Blue Ocean Strategy suggests that an organization should create new demand in an uncontested market space, or a "Blue Ocean", rather than compete head-to-head with other suppliers in an existing industry. The metaphor of red and blue oceans describes the market universe. Red oceans represent all the industries in existence today – the known market space. In the red oceans, industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and the competitive rules of the game are known. Here companies try to outperform their rivals to grab a greater share of product or service demand. As the market space gets crowded, prospects for profits and growth are reduced. Products become commodities or niche, and cutthroat competition turns the ocean bloody; hence, the term red oceans. Blue oceans, in contrast, denote all the industries not in existence today – the unknown market space, untainted by competition. In blue oceans, demand is created rather than fought over. There is ample opportunity for growth that is both profitable and rapid. In blue oceans, competition is irrelevant because the rules of the game are waiting to be set. Blue ocean is an analogy to describe the wider, deeper potential of market space that is not yet explored. The cornerstone of Blue Ocean Strategy is 'Value Innovation'. A blue ocean is created when a company achieves value innovation that creates value simultaneously for both the buyer and the company. The innovation (in product, service, or delivery) must raise and create value for the market, while simultaneously reducing or eliminating features or services that are less valued by the current or future market. The authors criticize Michael Porter's idea that successful businesses are either low-cost providers or niche-players. Instead, they propose finding value that crosses conventional market segmentation and offering value and lower cost. Educator Charles W. L. Hill proposed this idea in 1988 and claimed that Porter's model was flawed because differentiation can be a means for firms to achieve low cost. He proposed that a combination of differentiation and low cost might be necessary for firms to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. Many others have proposed similar strategies. For example, Swedish educators Jonas Ridderstråle and Kjell Nordström in their 1999 book Funky Business follow a similar line of reasoning. For example, "competing factors" in Blue Ocean Strategy are similar to the definition of "finite and infinite dimensions" in Funky Business. Just as Blue Ocean Strategy claims that a Red Ocean Strategy does not guarantee success, Funky Business explained that "Competitive Strategy is the route to nowhere". Funky Business argues that firms need to create "Sensational Strategies". Just like Blue Ocean Strategy, a Sensational Strategy is about "playing a different game" according to Ridderstråle and Nordström. Ridderstråle and Nordström also claim that the aim of companies is to create temporary monopolies. Kim and Mauborgne explain that the aim of companies is to create blue oceans that will eventually turn red. This is the same idea expressed in the form of an analogy. Ridderstråle and Nordström also claimed in 1999 that "in the slow-growth 1990s overcapacity is the norm in most businesses". Kim and Mauborgne claim that blue ocean strategy makes sense in a world where supply exceeds demand. Blue ocean strategy vs. red ocean strategy Kim and Mauborgne argue that while traditional competition-based strategies (red ocean strategies) are necessary, they are not sufficient to sustain high performance. Companies need to go beyond competing. To seize new profit and growth opportunities they also need to create blue oceans. The authors argue that competition based strategies assume that an industry’s structural conditions are given and that firms are forced to compete within them, an assumption based on what academics call the structuralism view, or environmental determinism. To sustain themselves in the marketplace, practitioners of red ocean strategy focus on building advantages over the competition, usually by assessing what competitors do and striving to do it better. Here, grabbing a bigger share of the market is seen as a zero-sum game in which one company’s gain is achieved at another company’s loss. Hence, competition, the supply side of the equation, becomes the defining variable of strategy. Here, cost and value are seen as trade-offs and a firm chooses a distinctive cost or differentiation position. Because the total profit level of the industry is also determined exogenously by structural factors, firms principally seek to capture and redistribute wealth instead of creating wealth. They focus on dividing up the red ocean, where growth is increasingly limited. Blue ocean strategy, on the other hand, is based on the view that market boundaries and industry structure are not given and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players. This is what the authors call “reconstructionist view”. Assuming that structure and market boundaries exist only in managers’ minds, practitioners who hold this view do not let existing market structures limit their thinking. To them, extra demand is out there, largely untapped. The crux of the problem is how to create it. This, in turn, requires a shift of attention from supply to demand, from a focus on competing to a focus on value innovation – that is, the creation of innovative value to unlock new demand. This is achieved via the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low-cost. As market structure is changed by breaking the value/cost trade-off, so are the rules of the game. Competition in the old game is therefore rendered irrelevant. By expanding the demand side of the economy new wealth is created. Such a strategy therefore allows firms to largely play a non–zero-sum game, with high payoff possibilities.