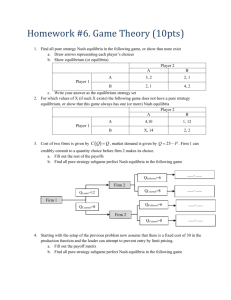

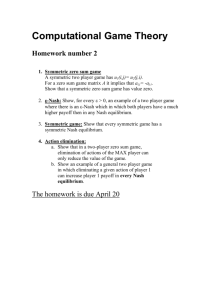

Managerial Economics & Business Strategy

advertisement

Game Theory: Inside Oligopoly Introduction • Behavior of competitors, or impact of own actions, cannot be ignored in oligopoly • Managers maximize profit or market share by outguessing competitors • Insight into oligopolistic markets by using GAME THEORY (Von Neumann and Morgenstern in 1950): designed to evaluate situations with conflicting objectives or bargaining processes between at least two parties. Types of Games • Normal Form • Simultaneous (act without knowing other player’s strategy) • One Shot • Zero Sum (market share) vs. Extensive Form vs. Sequential (one player moves after observing others) vs. Repeated (infinite and finite with uncertain and certain final period) vs. Non-zero Sum (profit maximization) A Normal Form Game Elements of the game: Player 2 Player 1 Planed decision or actions Strategy a b c Players Strategies or feasible actions Payoff matrix A B C 12,11 11,10 10,15 11,12 10,11 10,13 14,13 12,12 13,14 Results from strategy dependent on the strategies of all the players Dominant Strategy • Regardless of whether Player 2 chooses A, B, or C, Player 1 is better off choosing “a”! (Indiana Jones and the Holy Grail) • “a” is Player 1’s Dominant Strategy! Player 1 Player 2 Strategy a b c 1’s best strategy A 12,11 11,10 10,15 a B 11,12 10,11 10,13 a C 14,13 12,12 13,14 a 2’s best strategy c c a The Outcome • What should player 2 do? • 2 has no dominant strategy, but should reason that 1 will play “a”. • Therefore 2 should choose “C”. Player 1 Player 2 Strategy a b c A B C 12,11 11,12 14,13 14,13* 11,10 10,15 10,11 10,13 12,12 13,14 • This outcome is called a Nash equilibrium (set of strategies were no player can improve payoffs by unilaterally changing own strategy given other player’s strategy) •“a” 1’s best response to “C” and “C” is 2’s best response to “a”. Best Response Strategy • • • • • Try to predict the likely action of competitor to identify your best response: Conjecture choice of rival Select your own best response Was conjecture reasonable or Look for dominant strategies Put yourself in your rival’s shoes Market-Share Game Equilibrium • Two managers want to maximize market share (zero-sum game) • Strategies are pricing decisions • Simultaneous moves • One-shot game Manager 1 Manager 2 Strategy P=$10 P=$5 P=$1 P=$10 .5, .5 .8, .2 .9, .1 P=$5 .2, .8 .5, .5 .8, .2 Nash Equilibrium P = $1 .1, .9 .2, .8 .5, .5* Dominated Strategy • Dominance exception rather than rule • In absence of dominance it might be possible to simplify the game by eliminating dominated strategy (never played: lowest payoff regardless of other player’s strategy) • Steelers trial by 2, have the ball & enough time for 2 plays • Payoff matrix in yards gained by offense: no dominant strategy • Pass dominant offense without Blitz (dominated defense) Offense Defense Strategy Run Pass Best Offense Defend Run Defend Pass Blitz 2 6 14 Best Defense Run 8 7* 10 Pass Pass Pass Run Maximin or Secure Strategy In absence of dominant strategy risk averse players may abandon Nash or best response (*) and seek maximin option (^) that maximizes the minimum possible payoff. This is not design to maximize payoff but rather to avoid highly unfavorable outcomes (choose the best of all worst). Firm 1 Firm 2 Strategy None New Product Best for 1 Min for 2 None 4, 4^ 6, 3* New 6 None 3 Best New Product for 2 New 6 3, 6* None 3 2, 2 None 3 New 2 Min for 1 New 3 None 2 Board of Getty Oil agreed to sell 40% stake to Pennzoil @ $128.5 in Jan 1984. Board of Getty Oil subsequently accepted Texaco’s offer for 100% @ $128. Pennzoil sued Texaco for breach of contract & received $10 bill jury award in 1985. Texaco appealed. Before Supreme Court’s decision, they settled for $3 bill in 1987 . Examples of Coordination Games • Industry standards • size of floppy disks • size of CDs • etc. • National standards • electric current • traffic laws • etc. A Coordination Problem: Three Nash Equilibria! Player 1 Player 2 Strategy 1 2 3 A B C 0,0 0,0 $10,$10* $10,$10* 0,0 0,0 0,0 $10, $10* 0,0 Key Insights: • In some cases one-shot, non-cooperative games result in undesirable outcome for individuals (prisoner’s dilemma) and some times for society (advertisement). • Communication can help solve coordination problems. • Sequential moves can help solve coordination problems. • Time in jail, Nash (*) and Maximin (^) equilibrium in Prisoner’s dilemma. Suspect 1 Suspect 2 Strategy Confess Do Not Best for 1 Max for 2 Confess 5, 5*^ 15, 2 Confess Confess Do Not 2, 15 0, 0* Do Not Confess Best for 2 Confess Do Not Max for 1 Confess Confess One-Shot Advertising Game Equilibrium • Kellogg’s & General Mills want to maximize profits • Strategies consist of advertising campaigns • Simultaneous moves • One-shot interaction • Repeated interaction Kellogg’s General Mills Strategy None Moderate High None 12,12 20, 1 15, -1 Moderate 1, 20 6, 6 9, 0 High -1, 15 0, 9 2, 2* Nash Equilibrium Repeating the game 2 times will not improve outcome • In the last period the game is a one-shot game, so equilibrium entails High Advertising. • Period 1 is “really” the last period, since everyone knows what will happen in period 2. • Equilibrium entails High Advertising by each firm in both periods. Kellogg’s • The same holds true if we repeat the game any known, finite number of times. General Mills Strategy None Moderate High None Moderate 12,12 * 1, 20 20, 1 6, 6 15, -1 9, 0 High -1, 15 0, 9 2, 2* Nash Equilibrium Can collusion work if firms play the game each year, forever? • Consider the “trigger strategy” by each firm: • “Don’t advertise, provided the rival has not advertised in the past. If the rival ever advertises, “punish” it by engaging in a high level of advertising forever after.” • Each firm agrees to “cooperate” so long as the rival hasn’t “cheated”, which triggers punishment in all future periods. • “Tit-for-tat strategy” of copying opponents move from the previous period dominates “trigger strategy” for: • Simple to understand • Never invites nor rewards cheating • Forgiving: allows cheater to restore cooperation by reversing actions Suppose General Mills adopts this trigger strategy. Kellogg’s profits? Cooperate = 12 +12/(1+i) + 12/(1+i)2 + 12/(1+i)3 + … Value of a perpetuity of $12 paid = 12 + 12/i at the end of every year Cheat = 20 +2/(1+i) + 2/(1+i)2 + 2/(1+i)3 + … = 20 + 2/i Kellogg’s General Mills Strategy None Moderate High None 12,12 20, 1 15, -1 Moderate 1, 20 6, 6 9, 0 High -1, 15 0, 9 2, 2 Kellogg’s Gain to Cheating: • Cheat - Cooperate = 20 + 2/i - (12 + 12/i) = 8 - 10/i • Suppose i = .05 • Cheat - Cooperate = 8 - 10/.05 = 8 - 200 = -192 • It doesn’t pay to deviate. • Collusion is a Nash equilibrium in the infinitely repeated game! Kellogg’s General Mills Strategy None Moderate High None 12,12 20, 1 15, -1 Moderate 1, 20 6, 6 9, 0 High -1, 15 0, 9 2, 2 Benefits & Costs of Cheating • Cheat - Cooperate = 8 - 10/i • 8 = Immediate Benefit (20 - 12 today) • 10/i = PV of Future Cost (12 - 2 forever after) • If Immediate Benefit > PV of Future Cost • Pays to “cheat”. • If Immediate Benefit PV of Future Cost • Doesn’t pay to “cheat”. Kellogg’s General Mills Strategy None Moderate High None 12,12 20, 1 15, -1 Moderate 1, 20 6, 6 9, 0 High -1, 15 0, 9 2, 2 Key Insight • Collusion can be sustained as a Nash equilibrium when game lasts infinitely many periods or finitely many periods with uncertain “end”. • Doing so requires: • • • • Ability to monitor actions of rivals Ability (and reputation for) punishing defectors Low interest rate High probability of future interaction Real World Examples of Collusion: Garbage Collection Industry Homogeneous products Bertrand oligopoly Known identity of customers Known identity of competitors Firm 2 One-Shot Bertrand (Nash) Equilibrium Strategy Low Price High Price 0,0* 20,-1 Firm 1 Low Price High Price -1, 20 15, 15 Firm 2 Repeated Game Equilibrium Strategy Low Price High Price 0,0 20,-1 Firm 1 Low Price High Price -1, 20 15, 15* Real World Examples of Collusion: OPEC One-Shot Cournot (Nash) Equilibrium Repeated Game Equilibrium Assuming a Low Interest Rate Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabia • Cartel founded in 1960 by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudis and Venezuela: “to co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among Members in order to secure fair and stable prices” • Absent collusion: PCompetition < PCournot (OPEC) < PMonopoly Venezuela Strategy High Q Med Q Low Q High Q 5, 3 6, 7 8, 1 Med Q 9,4 12,10* 10, 18 Low Q 3, 6 20, 8 18, 15 Venezuela Strategy High Q Med Q Low Q High Q 5, 3 6, 7 8, 1 Med Q 9,4 12,10 10, 18 Low Q 3, 6 20, 8 18, 15* OPEC’s Demise 40 35 Low Interest Rates High Interest Rates 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1970 -5 1972 1974 1976 1978 Real Interest Rate 1980 1982 1984 Price of Oil 1986 Simultaneous-Move Bargaining • • • • Management and a union are negotiating a wage increase. Strategies are wage offers & wage demands. Simultaneous, one-shot move at making a deal. Successful negotiations lead to $600 million in surplus (to be split among the parties), failure results in a $100 million loss to the firm and a $3 million loss to the union. • Experiments suggests that, in the absence of any “history,” real players typically coordinate on the “fair outcome” • When there is a “bargaining history,” other outcomes may prevail Three Nash Equilibriums in Normal Form Management Union Strategy W = $10 W = $5 W = $10 100, 500* -100, -3 W = $5 -100, -3 300, 300* W = $1 -100, -3 -100, -3 W = $1 -100, -3 -100, -3 500, 100* Single Offer Bargaining • Now suppose the game is sequential in nature, and management gets to make the union a “take-it-orleave-it” offer. • Analysis Tool: Write the game in extensive form • • • • • Summarize the players Their potential actions Their information at each decision point The sequence of moves and Each player’s payoff To get The Game in Extensive Form Step 1: Management’s Move Step 2: Add the Union’s Move Step 3: Add the Payoffs Accept Union Reject 100, 500 -100, -3 10 Firm 5 Union Accept Reject 1 Accept Union Reject 300, 300 -100, -3 500, 100 -100, -3 Step 4: Identify Nash Equilibriums Outcomes such that neither player has an incentive to change its strategy, given the strategy of the other Accept 100, 500 Union Reject -100, -3 Accept 300, 300 10 Firm 5 Union Reject 1 Accept -100, -3 500, 100 Union Reject -100, -3 Step 5: Find the Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibriums Outcomes where no player has an incentive to change its strategy, given the strategy of the rival, that are based on “credible actions”: not the result of “empty threats” (not in its “best self interest”). Accept 100, 500 Reject -100, -3 Union 10 Firm 5 Union Accept Reject 1 Accept Union Reject 300, 300 -100, -3 500, 100 -100, -3 Re-Cap • In take-it-or-leave-it bargaining, there is a first-mover advantage. • Management can gain by making a take-it or leave-it offer to the union. But... • Management should be careful, however; real world evidence suggests that people sometimes reject offers on the the basis of “principle” instead of cash considerations. Pricing to Prevent Entry: An Application of Game Theory Two firms: an incumbent and potential entrant. Identify Nash and then Subgame Perfect Equilibria. -1, 1 Hard Incumbent Enter Soft Entrant Out 5, 5* 0, 10 Establishing a reputation for being unkind to entrants can enhance long-term profits. It is costly to do so in the short-term, so much so that it isn’t optimal to do so in a one-shot game. The Value of a Bad Reputation: Price Retaliation • In early 1970s General Foods’ Maxwell House dominated the non-instant coffee market in the Eastern USA, while Proctor & Gamble’s Folgers dominate Western USA. • In 1971 P&G started advertising & distributing Folgers in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. • GF’s immediately increased advertisement & lowered prices (sometimes below cost) in these regions & midwestern cities (Kansas City) where both marketed. • GF’s profit dropped from 30% in 1970 to –30% in 1974. When P&G reduced its promotional activities, GF’s price increased and profits were restored. Limit Pricing • Strategy where an incumbent prices below the monopoly price in order to keep potential entrants out of the market. • Goal is to lessen competition by eliminating potential competitors’ incentives to enter the market. • Incumbent produces QL instead of monopoly output QM. • Resulting price, PL, is lower than monopoly price PM. • Residual demand curve is the market demand DM minus QL. • Entry is not profitable because entrant’s residual demand lies below AC • Optimal limit pricing results in a residual demand such that, if the entrant entered and produced Q units, its profits would be zero. $ M MC PM AC AC M DM Q QM MR $ (DM – QL) Entrant's residual demand curve PM PL AC P = AC D Q QM QL M Quantity