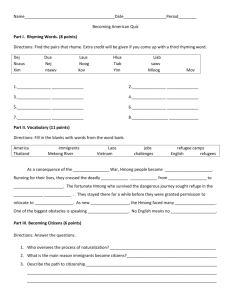

Laos_Background Paper

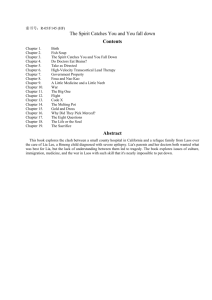

advertisement