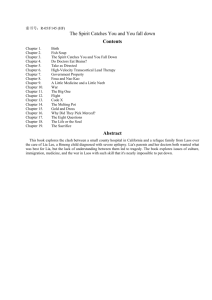

When the Spirit Catches You

advertisement

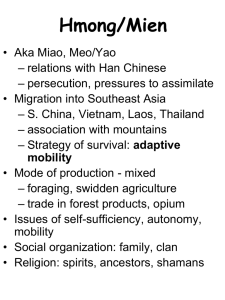

When the Spirit Catches You Commentary by R. Blystone Sept. 29, 2009 Few books other than textbooks have caused me to reread the tome multiple times and with extreme care. Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down is such a book and provoked a commentary. Lia Lee exists even today. If Lia was born an American child and found herself in a persistent vegetative state, her parents would have more than likely institutionalized her. And in institutional care, Lia would probably be dead today. Although the above is speculative, what does it say about U.S. society and what does it say about Hmong society? If you were a Hmong living in the mountains of Laos, what would you expect from life? You live in a world with no electricity; thus no appliances that thrive on a constant stream of electrons. You have no plumbing; thus no whoosh of the toilet after taking care of business. There are no medical doctors, no batteries for iPods, no tools from Home Depot, and no books for there are no libraries. Do the children go to school in the high mountains of Laos? What is there to study? The world contains about 5 million Hmongs with 3 million in southern China. Today the United States holds about a quarter of a million Hmongs fueled by our guilt to take care of those who fought in the Secret War. Today Laos still holds 500,000 Hmongs with many living quietly and secretively around Phou Bai, the tallest mountain in Laos (9400 feet). The Secret War, not publically admitted by the US until 1997 (30 years later), was built on the backs of the Hmong or Montagnards, as the French called them. Over 12,000 Hmong men were killed with countless thousands wounded in this anonymous war. These men pulled downed US pilots to safety from the Pathet Lao communists and the North Vietnam Army. From 1964 to 1973 more ordinance was dropped on Laos than the whole of the Second World War. It is estimated that 80,000,000 unexploded US bombs repose today in the ground of Laos. The Hmong collected a great deal of animosity from native Laotians by participating in the Secret War, a war that made Laos the most bombed country in history. Belying their simplistic life, the Hmong are not always peaceful people. They led a revolt against the French in 1919 in the “War of the Insane.” Over 60% of Hmong men were recruited by the CIA into the “Secret War.” The Chao Fa (Hmong guerrillas) fought the Pathet Lao after the Americans left. And as late as 2007 a group of 8 US-based Hmongs were trying to supply arms to Indochina Hmongs to force a coup d’état in Laos. Rebecca Sommer, a German filmmaker, documented the repression of Hmongs in Laos in 2008. In an abstract way the Hmongs resemble the Jews who were seeking a place to live after the atrocities committed upon them during World War II. Are the Hmongs in exodus? If so, is Laos their future Israel? How must the transplanted Hmongs feel, now living in the United States? Surrounded by 300,000,000 people previously placed into the American “melting pot.” How many previous immigrants to these shores came to escape tyranny and threats of death? How many immigrants came for a chance at a better future? We have asked how tolerant are Americans of the Hmongs. We have commented on how second and third generation Hmongs become Americanized or assimilated. But as the original immigrants to this country are lost from the collective family history by its increasing generations, do these descendents loose their tolerance of new immigrants? What is this relationship of the assimilated and the assimilators? As we grow older we each define and attain a sense of identity and personal philosophy. Imagine being a functioning caring adult managing a family and now being told you must change your perspective as you move onto new shores. You must tell time; you must live in a city; you must speak a new language; you must abandon the trappings that served you well where you were and adopt strange new ways. When in Rome do as the Romans do. But many Hmongs did not want to make this journey but merely to return to the mountains of Laos. But how could they; this is America, the land of opportunity. In opposition to the Hmongs’ story thread are the professional lives of Ernst and Philips. Husband and wife pediatricians, Neil and Peggy are well-trained medical professionals. For 20 years they center their professional lives in small Merced Community Hospital (MCMC). Rather than what could be a lucrative private practice, they settle in a public hospital facility in the middle part of California. Perhaps they were serving their sense of idealism by providing medical attention to those who could least afford it. While they were doing this they also were dealing with private family issues as they had a son with leukemia. In some ways their private war with leukemia paralleled the Lee’s war with spirit-driven epilepsy. Neil and Peggy provided contrast of the best of the Merced medical community to the worst in unassimilated behavior by Fuoa and Nao Kao, Lia’s transplanted Lao parents. Ernst and Philips speak for the whole of the frustration of the MCMC health care community. In many ways Fadiman’s book is not about Lia but rather two sets of parents: the Lees and Ernst/Philips. With the Lees living in one world, due to public assistance, their lives are centered on family and home. The Ernst/Philips on the other hand live in two worlds: their professional lives and their home life. Medical professionals can be consumed by their patients and home life is lost. Most do not find this desirable. When Neil and Peggy go on vacation, the Lee’s do not understand why they abandoned their daughter. It could be argued that Fadiman’s story is not about the Lee’s at all, but rather they serve as the fodder for a story about how a medical husband and wife team try to live in two worlds: professional and private. Yet Fadiman sets up Peggy and Neil for criticism when she presents them the eight questions in Chapter 18. Is Fadiman being disingenuous?