Addiction: what every judge should know

advertisement

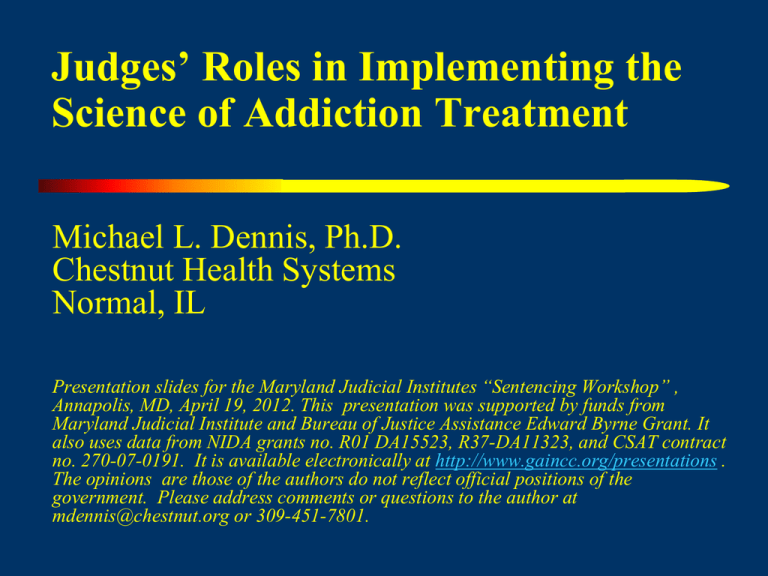

Judges’ Roles in Implementing the Science of Addiction Treatment Michael L. Dennis, Ph.D. Chestnut Health Systems Normal, IL Presentation slides for the Maryland Judicial Institutes “Sentencing Workshop” , Annapolis, MD, April 19, 2012. This presentation was supported by funds from Maryland Judicial Institute and Bureau of Justice Assistance Edward Byrne Grant. It also uses data from NIDA grants no. R01 DA15523, R37-DA11323, and CSAT contract no. 270-07-0191. It is available electronically at http://www.gaincc.org/presentations . The opinions are those of the authors do not reflect official positions of the government. Please address comments or questions to the author at mdennis@chestnut.org or 309-451-7801. Part 1. Chronic Nature of Addiction and the Correlates of Recovery 2 Science Learning Objectives Understand that Addiction is a Chronic Disease / Condition Identify the major predictors of positive treatment outcomes Understand that Recovery is broader than just abstinence and takes time 3 Brain Activity on PET Scan After Using Cocaine Rapid rise in brain activity after taking cocaine Actually ends up lower than they started 1-2 Min 3-4 5-6 6-7 7-8 8-9 9-10 10-20 20-30 Photo courtesy of Nora Volkow, Ph.D. Mapping cocaine binding sites in human and baboon brain in vivo. Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, Macgregor RIR, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Bendreim B, Gatley ST. et al. Synapse 1989;4(4):371-377. 4 Prolonged Substance Use Injures The Brain: Healing Takes Time Normal levels of brain activity in PET scans show up in yellow to red Reduced brain activity after regular use can be seen even after 10 days of abstinence Normal 10 days of abstinence After 100 days of abstinence, we can see brain activity “starting” to recover 100 days of abstinence Source: Volkow ND, Hitzemann R, Wang C-I, Fowler IS, Wolf AP, Dewey SL. Long-term frontal brain metabolic changes in cocaine abusers. Synapse 11:184-190, 1992; Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schlyer D, Dewey 5, Wolf AP. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse 14:169-177, 1993. 5 Adolescent Brain Development Occurs from the Inside to Out and Photo courtesy of the NIDA Web site.to FromFront A from Back Slide Teaching Packet: The Brain and the Actions of Cocaine, Opiates, and Marijuana. pain 6 6 Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse, Dependence and Problem Use Peaks at Age 20 100 90 80 70 Percentage 60 Over 90% of use and problems start between the ages of 12-20 People with drug dependence die an average of 22.5 years sooner than those without a diagnosis It takes decades before most recover or die Severity Category Other drug or heavy alcohol use in the past year Alcohol or Drug Use (AOD) Abuse or Dependence in the past year 50 40 30 20 10 0 65+ 50-64 35-49 30-34 21-29 18-20 16-17 14-15 12-13 Age Source: 2002 NSDUH and Dennis & Scott, 2007, Neumark et al., 2000 7 Overlap with Crime and Civil Issues Committing property crime, drug related crimes, gang related crimes, prostitution, and gambling to trade or get the money for alcohol or other drugs Committing more impulsive and/or violent acts while under the influence of alcohol and other drugs Crime levels peak between ages of 15-20 (periods or increased stimulation and low impulse control in the brain) Adolescent crime is still the main predictor of adult crime Parent substance use is intertwined with child maltreatment and neglect – which in turn is associated with more use, mental health problems and perpetration of violence on others 8 Yet Recovery is likely and better than average compared with other Mental Health Diagnoses SUD Remission Rates are BETTER than many other DSM Diagnoses 100% 90% 70% 58% Median of 8 to 9 years in recovery 31% 20% Drug Lifetime Diagnosis 8% 9% 4% 4% 7% 12% 11% 3% Posttraumatic Stress Alcohol 0% 15% 18% Mood : 7% 8% Anxiety : 10% 8% Any Internalizing 10% 10% Attention Deficit 10% 8% Intermittent Explosive 13% Oppositional Defiant 15% Any AOD 10% 46% 40% 39% 45% 25% 30% 20% 56% 48% 50% Conduct 40% 66% Any Externalizing 50% 89% 77% 80% 60% 89% 83% Past Year Recovery (no past year symptoms) Recovery Rate (% Recovery / % Dependent) Source: Dennis, Coleman, Scott & Funk forthcoming; National Co morbidity Study Replication 9 9 Percent still using People Entering Publicly Funded Treatment Generally Use For Decades It takes 27 years before half reach 1 or more years of abstinence or die 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 0 5 10 15 20 25 Years from first use to 1+ years of abstinence 30 10 Percent still using The Younger They Start, The Longer They Use 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Age of First Use under 15* 60% longer 15-20 21+ 0 5 10 15 20 25 Years from first use to 1+ years of abstinence 30 * 11 Percent still using The Sooner They Get To Treatment, The Quicker They Get To Abstinence Years to first Treatment Admission* 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 20 or more years 57% quicker 10 to 19 years 0 5 10 15 20 25 Years from first use to 1+ years of abstinence 0 to 9 30 years * 12 After Initial Treatment… Relapse is common, particularly for those who: – – – Are Younger Have already been to treatment multiple times Have more mental health issues or pain It takes an average of 3 to 4 treatment admissions over 9 years before half reach a year of abstinence Yet over 2/3rds do eventually abstain Treatment predicts who starts abstinence Self help engagement predicts who stays abstinent Source: Dennis et al., 2005, Scott et al 2005 13 . The Likelihood of Sustaining Abstinence After 4 years of Another Year Grows Over Time abstinence, about 100% % Sustaining Abstinence Another Year 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% Only a third of people with 1 to 12 months of abstinence will sustain it another year After 1 to 3 years of abstinence, 2/3rds will make it another year 86% will make it another year 86% 66% 36% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1 to 12 months 1 to 3 years Duration of Abstinence* Source: Dennis, Foss & Scott (2007) * p<.05 4 to 7 years But even after 7 years of abstinence, about 14% relapse each year1414 What does recovery look like on average? 1-12 Months Duration of Abstinence 1-3 Years 4-7 Years • More clean and sober friends • Less illegal activity and incarceration • Less homelessness, violence and victimization • Less use by others at home, work, and by social peers • Virtual elimination of illegal activity and illegal income • Better housing and living situations • Increasing employment and income • More social and spiritual support • Better mental health • Housing and living situations continue to improve • Dramatic rise in employment and income • Dramatic drop in people living below the poverty line Source: Dennis, Foss & Scott (2007) 15 15 Deaths in the next 12 months Sustained Abstinence Also Reduces The Risk of Death* The Risk of Death goes down with years of sustained abstinence Users/Early Abstainers more likely to die in the next 12 months It takes 4 or more years of abstinence for risk to get down to community levels (Matched on Gender, Race & Age) Source: Scott, Dennis, Laudet, Funk & Simeone (in press) * 16 Other factors related to death rates Death is more likely for those who – – – – – Are older Are engaged in illegal activity Have chronic health conditions Spend a lot of time in and out of hospitals Spend a lot of time in and out of substance abuse treatment Death is less common for those who – – – Have a greater percent of time abstinent Have longer periods of continuous abstinence Get back to treatment sooner after relapse Source: Scott, Dennis, Laudet, Funk & Simeone (2011) 17 The Cyclical Course of Relapse, Incarceration, Treatment and Recovery (Pathway Adults) Over half change status annually P not the same in both directions Incarcerated (37% stable) 6% 7% 25% 30% In the Community Using (53% stable) 13% 8% 28% In Recovery (58% stable) 29% 4% 44% 31% In Treatment (21% stable) Source: Scott, Dennis, & Foss (2005) 7% Treatment is the most likely path to recovery 18 Predictors of Change Also Vary by Direction Probability of Transitioning from Using to Abstinence - mental distress (0.88) + older at first use (1.12) -ASI legal composite (0.84) + homelessness (1.27) + # of sober friend (1.23) + per 8 weeks in treatment (1.14) In the Community Using (53% stable) 28% In Recovery (58% stable) 29% Probability of Sustaining Abstinence - times in treatment (0.83) + Female (1.72) - homelessness (0.61) + ASI legal composite (1.19) - number of arrests (0.89) + # of sober friend (1.22) + per 77 self help sessions (1.82) Source: Scott, Dennis, & Foss 19 Summary of Key Points Addiction is a brain disorder with the highest risk being during the period of adolescent to young adult brain development Addiction is chronic in the sense that it often lasts for years, the risk of relapse is high, and multiple interventions are likely to be needed Yet over two thirds of the people with addiction do achieve recovery Treatment increases the likelihood of transitioning from use to recovery Self help, peers and recovery environment help predict who stays there Recovery is broader than just abstinence 20 Part 2. The Need and Value of Standardized Screening 21 Science Learning Objectives To show the large gap between need for and receipt of substance abuse treatment To demonstrate the feasibility, validity and usefulness of low cost screening to identify substance use and co-occurring mental health, monitor placement, and predict the risk of recidivism 22 While Substance Use Disorders are Common, Treatment Participation Rates Are Low Over 88% of adolescent and young adult treatment and over 50% of adult treatment is publicly funded Few Get Treatment: 1 in 20 adolescents, 1 in 18 young adults, 1 in 11 adults 25% Much of the private funding is limited to 30 days or less and authorized day by day or week by week 20.1% 20% 15% 10% 7.4% 7.0% 5% 1.1% 0.4% 0.6% 0% 12 to 17 18 to 25 Abuse or Dependence in past year 26 or older Treatment in past year Source: SAMHSA 2010. National Survey On Drug Use And Health, 2010 [Computer file] 23 93% 97% 95% 95% Potential AOD Screening & Intervention Sites: Adolescents (age 12-17) 80% 60% 40% 20% 1% 1% 1% 10% 0% 1% 4% 8% 1% 3% 9% 15% 4% 5% 8% 11% 12% 13% 12% 23% 29% 35% 41% 49% 30% 41% 42% 46% % Any Contact 100% 0% SUD Tx No use in past year Detention Prob/Parole Hosptial Less than weekly use MH Tx Emer. Dept. Weekly Use Work School Abuse or dependence Source: SAMHSA 2010. National Survey On Drug Use And Health, 2010 [Computer file] 24 Potential AOD Screening & Intervention Sites: Adults (age 18+) Source: SAMHSA 2010. National Survey On Drug Use And Health, 2010 [Computer file] 25 Juvenile Justice (n=2,024) High on Mental Health 12% 11% Student Assistance Programs (n=8,777) 61% 60% 75% 75% 46% 35% 73% 62% 40% 37% Substance Abuse Treatment (n=8,213) Either Problems could be easily identified 12% 12% Virtually all Sub. Use co-occurring in school 77% 67% 57% 47% 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 86% 83% Adolescent Rates of High (2+) Scores on Mental Health (MH) or Substance Abuse (SA) Screener by Setting in WA State Mental Health Treatment (10,937) Children's Administration (n=239) High on Substance High on Both Source: Lucenko et al. (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ 26 4% 3% 17% 17% 18% 17% Lower than expected rates of SA in mental health & children’s admin 69% 69% 44% 51% 31% 64% 43% 53% 31% 65% 51% 46% 78% 73% 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 81% 68% 69% 56% Adult rates of High (2+) Scores on Mental Health (MH) or Substance Abuse (SA) Screener by Setting in WA State Substance Abuse Treatment (n=75,208) Either Eastern State Hospital (n=422) Corrections: Community (n=2,723) High on Mental Health Corrections: Prison (n=7,881) Mental Health Childrens Treatment Administration (55,847) (n=1,238) High on Substance High on Both Source: Lucenko et al. (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ 27 Adolescent Client Validation of High Co-Occurring from GAIN Short Screener vs. Clinical Records by Setting in WA State Substance Abuse Treatment (n=8,213) Juvenile Justice (n=2,024) GAIN Short Screener Mental Health Treatment (10,937) 9% 11% 15% 12% 34% 35% 56% Two-page measure closely approximated all found in the clinical record after the next 2 years 47% 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Children's Administration (n=239) Clinical Indicators Source: Lucenko et al. (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ 28 Higher rate in clinical record in mental health and children’s administration (But that was past on “any use” vs. “abuse/dependence” and 2 years vs. past year) 3% 17% 22% 39% 59% 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 56% Adult Client Validation of High Co-Occurring from GAIN Short Screener vs. Clinical Records by Setting in WA State Substance Abuse Treatment (n=75,208) Mental Health Treatment Childrens Administration (55,847) (n=1,238) GAIN Short Screener Clinical Indicators Source: Lucenko et al. (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ 29 Where in the System are the Adolescents with Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Co-occurring? 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 Any Behavioral Health (n=22,879) Mental Health (21,568) Substance Abuse Need (10,464) Co-occurring (9,155) Substance Abuse Treatment Juvenile Justice Children's Administration School Assistance Programs (SAP) largest part of BH/MH system; 2nd largest of SA & Cooccurring systems Student Assistance Program Mental Health Treatment Source: Lucenko et al (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ 30 Where in the System are the Adults with Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Co-occurring? More Mental Health than Substance Abuse Source: Lucenko et al (2009). Report to the Legislature: Co-Occurring Disorders Among DSHS Clients. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services. Retrieved from http://publications.rda.dshs.wa.gov/1392/ % within Level of Care Total Disorder Screener Severity Disorder Screener for Adolescents by Level ofTotal Care: Adolescents 11% Lo Mod. High -> 10% w 9% 8% 7% 6% 5% 4% 3% 2% 1% 0% 0 1 2 3 4 5 Outpatient Median=6.0 Residential (n=1,965) OP/IOP (n=2,499) Residential Median= 10.5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Few Total Disorder Sceener (TDScr) Score missed (1/2-3%) About 41% of Resid are below 10 About 30% of OP are in the high severity likelyand typical Source: SAPISP(more 2009 Data DennisOP et al 2006 range more typical of residential 32 Total Disorder Screener Severity Total Disorder Screener for Adults by Level of Care: Adults % within Level of Care 12% Outpatient Lo Mod. High -> Residential (n=1,965) 11% Median=4.5 10% w (29% at 10+) OP/IOP (n=2,499) 9% 8% Youth have to be 7% more severe on 6% average to access 5% services 4% 3% Residential 2% Median= 8.5 1% (41% below) 0% 10% of 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 adult OP Total Disorder Sceener (TDScr) Score missed) Source: SAPISP 2009 Data and Dennis et al 2006 33 Any Illegal Activity in the Next Twelve Months by Intake Severity on Crime/Violence and Substance Disorder Screeners Any Illegal Activity (months1-6) 61% 60% 55% 42% 40% 30% 35% 41% 29% 30% 20% 17% High Mod 0% High Mod Low Low Crime/Violence Screener (past year at Intake) Source: CSAT 2010 Summary Analytic Dataset (n=20,982) Substance Disorder Screener (past year at Intake) 34 Predictive Power of Simple Screener Crime/ Violence Screener Low (0) Low (0) Low (0) Mod (1-2) Mod (1-2) Mod (1-2) High (3-5) High (3-5) High (3-5) Substance Disorder Screener Low (0) Mod (1-2) High (3-5) Low (0) Mod (1-2) High (3-5) Low (0) Mod (1-2) High (3-5) 12 Month Recidivism Rate 17% 29% 30% 30% 35% 42% 41% 55% 61% Odds Ratio \a 1.0 2.0* 2.1* 2.1* 2.6* 3.5* 3.4* 6.0* 7.6* * p<.05 \a Odds of row (%/(1-%) over low/low odds across all groups Source: CSAT 2010 Summary Analytic Dataset (n=20,932) 35 Summary of Key Points There is a large gap between those getting treatment and those in need, ranging from 1-20 adolescents to 1 in 11 adults The people in need are coming into contact with a range of systems that could serve as screening sites where problems could be identified and addressed before people end up in the courts Simple Screening tools are feasible, valid and useful to identify substance use disorders, co-occurring behavioral health, monitor placement and predict the risk of recidivism 36 Part 3. What works in Treatment? 37 Science Learning Objectives Define what we mean by treatment Hand out NIDA handbook on the Principals of Addiction Treatment in the Justice System Identify the key predictors of effectiveness Highlight some of the serious limitations and problems of the current public treatment 38 What is Treatment? Motivational Interviewing and other protocols to help them understand how their problems are related to their substance use and that they are solvable Residential, IOP and other types of structured environments to reduce short term risk of relapse Detoxification and medication to reduce pain/risk of withdrawal and relapse, including tobacco cessation Evaluation of antecedents and consequences of use Community Reinforcement Approaches (CRA) Relapse Prevention Planning Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Proactive urine monitoring Motivational Incentives / Contingency Management Access to communities of recovery for long term support, including 12-step, recovery coaches, recovery schools, recovery housing, workplace programs Continuing care, phases for multiple admission 39 Other Specific Services that are Screened for and Needed by People in Treatment: Trauma, suicide ideation, and para-suicidal behavior Child maltreatment and domestic violence interventions (not just reporting protocols) Psychiatric services related to depression, anxiety, ADHD/Impulse control, conduct disorder/ ASPD/ BPD, Gambling Anger Management HIV Intervention to reduce high risk pattern of behavior (sexual, violence, & needle use) Tobacco cessation Family, school and work problems Case management and work across multiple systems of care and time 40 Number of Problems by Level of Care (Triage) 100% 90% 0 to 1 80% 2 to 4 70% 60% 5 or more 50% 40% 67% 30% 20% 50% 78% 55% 39% 10% 0% Outpatient (OR=1) Intensive Outpatient (OR=1.6) Long Term Residential (OR=1.9) Source: Dennis et al 2009; CSAT 2007 Adolescent Treatment Outcome Data Set (n=12,824) Med. Term Residential (OR=3.2) * Short Term Residential (OR=5.5) Clients entering Short Term Residential (usually dual diagnosis) have 5.5 times higher odds of having 5+ major problems* (Alcohol, cannabis, or other drug disorder, depression, anxiety, trauma, suicide, ADHD, CD, victimization, violence/ illegal activity) 41 No. of Problems* by Severity of Victimization 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% None One Two Three Four Five+ 70% 45% 15% Low (OR 1.0) Mod. (OR=4.6) High (OR=13.2) Those with high lifetime levels of victimization have 13 times higher odds of having 5+ major problems* Severity of Victimization Source: Dennis et al 2009; CSAT 2007 Adolescent Treatment Outcome Data Set (n=12,824) * (Alcohol, cannabis, or other drug disorder, depression, anxiety, trauma, suicide, ADHD, CD, victimization, violence/ illegal activity) 42 Components of Comprehensive Drug Addiction Treatment Recommended by NIDA www.drugabuse.gov 43 Two Key Resources Available from NIDA (http://www.drugabuse.gov ) 44 Major Predictors of Bigger Effects 1. A strong intervention protocol based on prior evidence 2. Quality assurance to ensure protocol adherence and project implementation 3. Proactive case supervision of individual 4. Triage to focus on the highest severity subgroup 45 Impact of the numbers of these Favorable features on Recidivism in 509 Juvenile Justice Studies in Lipsey Meta Analysis Average Practice Source: Adapted from Lipsey, 1997, 2005 The more features, the lower the recidivism 46 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Interventions that Typically do Better than Usual Practice in Reducing Juvenile Recidivism (29% vs. 40%) Aggression Replacement Training Reasoning & Rehabilitation Moral Reconation Therapy Thinking for a Change Interpersonal Social Problem Solving MET/CBT combinations and Other manualized CBT Multisystemic Therapy (MST) Functional Family Therapy (FFT) Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) Assertive Continuing Care NOTE: There is generally little or no differences in mean effect size between these brand names Source: Adapted from Lipsey et al 2001, Waldron et al, 2001, Dennis et al, 2004 47 Impact of Simple On-site Urine Protocol with Feedback On False Negative Urines 25% Off Site 19% 20% 15% 15% On-Site With Immediate Feedback 10% 5% On-site Urine Feedback Protocol associated with Lower False Negatives (19 v 3%) 5% 3% 0% Mon 12 Source: Scott & Dennis (in press) Mon 24 48 Implementation is Essential (Reduction in Recidivism from .50 Control Group Rate) The best is to have a strong program implemented well Thus one should optimally pick the strongest intervention that one can implement well Source: Adapted from Lipsey, 1997, 2005 The effect of a well implemented weak program is as big as a strong program implemented poorly 49 Less than half stay the 90 or more days Recommended by Research 100% 90% 80% 1% 16% 28% 29% 91+ days 46% 70% 31 to 90 days 60% 50% 0 to 30 days 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Detox Residential IOP OP Total (n=341,866) (n=317,967) (n=182,465) (n=786,707) (n=1,629,005) Source: Office of Applied Studies 2007Discharge – Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/dasis.htm 50 Less than Half are Positively Discharged Transfer rates from higher levels of care are dismal 100% 90% 34% 80% 70% 45% 52% Completed 65% 60% 22% 50% Transferred 14% 15% 40% 30% 36% AMA 16% 12% ASR 20% 10% Other 0% Detox (n=341,848) Residential (n=317,945) IOP (n=182,441) OP Total (n=786,662) (n=1,628,896) Source: Office of Applied Studies 2007 Discharge – Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/dasis.htm 51 Programs often LACK Evidenced Based Assessment to Identify and Practices to Treat: Substance use disorders (e.g., abuse, dependence, withdrawal), readiness for change, relapse potential and recovery environment Common mental health disorders (e.g., conduct, attention deficit-hyperactivity, depression, anxiety, trauma, self-mutilation and suicidal thoughts) Crime and violence (e.g., inter-personal violence, drug related crime, property crime, violent crime) HIV risk behaviors (needle use, sexual risk, victimization) Child maltreatment (physical, sexual, emotional) Recovery environment and peer risk 52 Summary of Key Points Over half the people present to substance abuse treatment with 5 or more overlapping problems that require a range of interventions The best predictors of outcome are the use of evidenced based assessment and practice that have worked for others, have strong quality assurance, strong case supervision, and good triage of services to well defined problems. Conversely, the lack of evidenced based assessment, treatment practices and resources leads to high drop out 53 Part 4. What makes Drug Treatment Courts Effective? 54 Science Learning Objectives Describe rational and key components associated with Drug Treatment Court Success Evaluate the state of the evidence on the effectiveness of drug treatment courts Highlight the most recent findings on the effectiveness of juvenile treatment drug courts (JTDC) in general versus the more comprehensive/ trauma focused Reclaiming Futures JTDC 55 Screening & Brief Inter.(1-2 days) Outpatient (18 weeks) In-prison Therap. Com. (28 weeks) Intensive Outpatient (12 weeks) Adolescent Outpatient (12 weeks) Treatment Drug Court (46 weeks) Methadone Maintenance (87 weeks) Residential (13 weeks) Therapeutic Community (33 weeks) $70,000 $60,000 $50,000 $40,000 $30,000 $20,000 $0 SBIRT models popular due to ease of implementation and low cost $10,000 The Cost of Treatment Episode vs. Consequences $407 • $750 per night in Medical Detox $1,132 • $1,115 per night in hospital $1,249 • $13,000 per week in intensive $1,384 care for premature baby $1,517 • $27,000 per robbery $2,486 • $67,000 per assault $4,277 $10,228 $14,818 $22,000 / year to incarcerate an adult $30,000/ child-year in foster care $70,000/year to keep a child in detention Source: French et al., 2008; Chandler et al., 2009; Capriccioso, 2004 in 2009 dollars 56 Return on Investment (ROI) 57 • Substance abuse treatment has been shown to have a ROI within the year of between $1.28 to $7.26 per dollar invested • Best estimates are that Treatment Drug Courts have an average ROI of $2.14 to $2.71 per dollar invested This also means that for every dollar treatment is cut, it costs society more money than was saved within the same year Source: Bhati et al., (2008); Ettner et al., (2006) 57 Key Components Adult & Juvenile Treatment Drug Courts 1. Formal screening process for early identification and referral for substance use and other disorders/needs 2. Multidimensional standardized assessment to guide clinical decision-making related to diagnosis, treatment planning, placement and outcome monitoring 3. Interdisciplinary-treatment drug court team 4. Comprehensive non-adversarial team-developed treatment plan, including youth and family 5. Continuum of substance-abuse treatment and other rehabilitative services to address the youths needs 6. Use of evidence-based treatment practices 58 Key Components Treatment Drug Court (cont.) 6. Monitoring progress through urine screens and weekly interdisciplinary-treatment drug court team staffings 7. Feedback to the judge followed by graduated performance-based rewards and sanctions 8. Reducing judicial involvement from weekly to monthly with evidence of favorable behavior change over a year or longer 9. Advanced agreement between parties on how on assessment information will be used to avoid selfincrimination 10. Use of information technology to connect parties and proactively monitor implementation at the client and program level Source: National Association of Drug Court Professionals, 1997; Henggeler et al., 2006; Ives et al., 2010. 59 Level of Evidenced is Available on Drug Treatment Courts Science Law Beyond a Reasonable Doubt STRONGER Meta Analyses of Experiments/ Quasi Experiments (Summary v Predictive, Specificity, Replicated, Consistency) Dismantling/ Matching study (What worked for Clear and whom) Convincing Experimental Studies (Multi-site, Independent, Evidence Replicated, Fidelity, Consistency) Preponderance Quasi-Experiments (Quality of Matching, Multiof the Evidence site, Independent, Replicated, Consistency) Pre-Post (multiple waves), Expert Consensus Probable Correlation and Observational studies Cause Case Studies, Focus Groups Reasonable Pre-data Theories, Logic Models Suspicion Anecdotes, Analogies 60 Source: Marlowe 2008, Ives et al 2010 Level of Evidenced is Available on Drug Treatment Courts Science Law AdultAnalyses Drug Treatment Courts: 5Quasi meta analyses Meta of Experiments/ of 76 studies found crimevreduced 7-26% with Experiments (Summary Predictive, $1.74 toReplicated, $6.32 return on investment Specificity, Consistency) Dismantling/ Matching study worked for DWI Treatment Courts: one (What quasi experiment Clear and and five observational studies positive findings whom) Convincing Experimental Studies (Multi-site, Independent, Evidence Family DrugFidelity, Treatment Courts: one multisite Replicated, Consistency) quasi experiment with positive findings for Preponderance Quasi-Experiments (Quality of Matching, Multiparent and child of the Evidence site, Independent, Replicated, Consistency) Pre-Post (multiple waves), Expert Juvenile Drug Treatment CourtsConsensus – one 2006 Probable Correlation andone Observational studies quasiexperiment, 2010 large multisite Cause Case Studies,&Focus Groups experiment, several small studies with similar Reasonable or better effects thanModels regular adolescent Pre-data Theories, Logic Suspicion outpatient treatment Anecdotes, Analogies 61 Source: Marlowe 2008, Ives et al 2010 Beyond a Reasonable Doubt STRONGER Of the Past 90 Days Change in Days of Abstinence* 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Intake* 12 Months Raw Change % Change Juvenile Treatment Drug Court (JTDC) \a 56 71 14 26% Reclaiming Futures JTDC (RF-JTDC) \a, b 55 79 23 42% * Days of abstinence from alcohol and other drugs while living in the community; If coming from detention at intake, based on the 90 days before detention. \a p<.05 that post minus pre change is statistically significant \b p<.05 that change for Reclaiming Futures JTDC is better than the average for other JTDC Source: CSAT 2010 SA Data Set subset to 1+ Follow ups 62 Change in Days of Victimization* Of the past 90 days 4 3 2 1 0 Intake 12 Months Raw Change % Change Juvenile Treatment Drug Court (JTDC) 0.69 0.95 0.26 37% Reclaiming Futures JTDC (RF-JTDC) \a, b 2.93 0.08 -2.85 -97% *Number of days victimized (physically, sexually, or emotionally ) in past 90 \a p<.05 that post minus pre change is statistically significant CSAT 2010 SA Data Set subset to 1+ Follow ups 63 Average Number of Crimes Change in Average Number of Crimes Reported 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Year Prior Year After Raw Change % Change Juvenile Treatment Drug Court (JTDC) /a 37 20 -16 -45% Reclaiming Futures JTDC (RF-JTDC) /a, b 36 14 -22 -60% \a p<.05 that post minus pre change is statistically significant \b p<.05 that change for Reclaiming Futures JTDC is better than the average for other JTDC CSAT 2010 SA Data Set subset to 1+ Follow ups 64 Average Number of Crimes Change in Average Number of Crimes Reported by Type* 20 15 10 5 0 Property JTDC /a Year Prior 16 Year After 8 Raw Change -8 % Change -48% Property RF-JTDC /a 18 9 -9 -48% Violent JTDC /a 6 4 -2 -29% Violent RF-JTDC /a, b 6 2 -4 -68% Drug/Other JTDC /a 15 8 -7 -46% Drug/Other RF-JTDC /a, b 11 3 -9 -76% *Sum of all crimes reported by type \a p<.05 that post minus pre change is statistically significant \b p<.05 that change for Reclaiming Futures JTDC is better than the average for other JTDC CSAT 2010 SA Data Set subset to 1+ Follow ups 65 Average Annual Cost of Crime Change in Cost of Crime to Society* $500,000 $400,000 $300,000 $200,000 $100,000 $0 Year Prior Year After Raw Change % Change Juvenile Treatment Drug Court (JTDC)\a $389,110 $321,661 -$67,449 -17% Reclaiming Futures JTDC (RF-JTDC)\a, b $403,991 $93,789 -$310,202 -77% *Based on the frequency of crime times the average cost to society of that crime estimated by McCollister et al (2010) in 2010 dollars; distribution capped at 99th percentile to minimize the impact of outliers.. \a p<.05 that post minus pre change is statistically significant \b p<.05 that change for Reclaiming Futures JTDC is better than the average for other JTDC CSAT 2010 SA Data Set subset to 1+ Follow ups 66 Return on Investment Increased Cost of Service Utilization\a Reduced Cost of Crime to Society\b Return on Investment Other JTDC RF-JTDC + $1,673 + $4,022 - $67,449 - $310,202 40 to 1 77 to 1 \a Based on change in youth reported cost of service utilization and other short term costs; DOES NOT include other real costs for implementing JTDC and/or RF-JTDC model and is therefor likely an underestimate \b Based on the frequency of crime times the average cost to society of that crime estimated by McCollister et al (2010) in 2010 dollars; distribution capped at 99th percentile to minimize the impact of outliers.. 67 Summary of Key Points Comprehensive, integrated, and collaborative drug courts are generally more effective While they are often small and cost more in services, drug treatment courts can produce high returns on investment relative to reduced costs to society More comprehensive models (like Reclaiming Futures) that focused on evidenced based assessment and treatment and providing more trauma/mental health services cost more but work even better and have even higher rates of return. 68 Other Resources you can use now Cost-Effective evidence-based practices A-CRA & MET/CBT tracks here, more at http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/ or http://www.chestnut.org/li/apss/CSAT/protocols/index.html Most withdrawal symptoms appeared more appropriate for ambulatory/outpatient detoxification, see http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0201/p495.html Trauma informed therapy and sucide prevention at http://www.nctsn.org/nccts and http://www.sprc.org/ Externalizing disorders medication & practices http://systemsofcare.samhsa.gov/ResourceGuide/ebp.html Tobacco cessation protocols for youth http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/quit_smoking/cessation/youth_tobacc o_cessation/index.htm HIV prevention with more focus on sexual risk and interpersonal victimization at http://www.who.int/gender/violence/en/ or http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/en/home.aspx For individual level strengths see http://www.chestnut.org/li/apss/CSAT/protocols/index.html For improving customer services http://www.niatx.net 69 References Applegate, B. K., & Santana, S. (2000). Intervening with youthful substance abusers: A preliminary analysis of a juvenile drug court. The Justice System Journal, 21(3), 281-300. Bhati et al. (2008) To Treat or Not To Treat: Evidence on the Prospects of Expanding Treatment to Drug-Involved Offenders. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Capriccioso, R. (2004). Foster care: No cure for mental illness. Connect for Kids. Accessed on 6/3/09 from http://www.connectforkids.org/node/571 Chandler, R.K., Fletcher, B.W., Volkow, N.D. (2009). Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: Improving public health and safety. Journal American Medical Association, 301(2), 183-190 Dennis, M. L., Scott, C. K. (2007). Managing Addiction as a Chronic Condition. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice , 4(1), 45-55. Dennis, M. L., Scott, C. K., Funk, R. R., & Foss, M. A. (2005). The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2 Suppl), S51-S62. Dennis, M. L., Titus, J. C., White, M., Unsicker, J., & Hodgkins, D. (2003). Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. (Version 5 ed.). Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems. Retrieved from www.gaincc.org. Dennis, M.L., White, M., Ives, M.I (2009). Individual characteristics and needs associated with substance misuse of adolescents and young adults in addiction treatment. In Carl Leukefeld, Tom Gullotta and Michele Staton Tindall (Ed.), Handbook on Adolescent Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment: Evidence-Based Practice. New London, CT: Child and Family Agency Press. Ettner, S.L., Huang, D., Evans, E., Ash, D.R., Hardy, M., Jourabchi, M., & Hser, Y.I. (2006). Benefit Cost in the California Treatment Outcome Project: Does Substance Abuse Treatment Pay for Itself?. Health Services Research, 41(1), 192-213. French, M.T., Popovici, I., & Tapsell, L. (2008). The economic costs of substance abuse treatment: Updated estimates of cost bands for program assessment and reimbursement. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35, 462-469 Henggeler, S. W., Halliday-Boykins, C. A., Cunningham, P. B., Randall, J., Shapiro, S. B., Chapman, J. E. (2006). Juvenile drug court: enhancing outcomes by integrating evidence-based treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 42-54. Institute of Medicine (2006). Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions . National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11470 Ives, M.L., Chan, Y.F., Modisett, K.C., & Dennis, M.L. (2010). Characteristics, needs, services, and outcomes of youths in juvenile treatment drug courts as compared to adolescent outpatient treatment. Drug Court Review, 7(1), 70 10-56. References Marlowe, D. (2008). Recent studies of drug courts and DWI courts: Crime reduction and cost savings. Miller, M. L., Scocas, E. A., & O’Connell, J. P. (1998). Evaluation of the juvenile drug court diversion program. Dover DE: Delaware Statistical Analysis Center, USA. National Association of Drug Court Professionals (1997). Defining Drug Courts: The Key Components. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/205621.pdf . National Institute on Drug Abuse (2000). Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. Rockville, MD: Author. NIH Publication No.00-4180 . On line at http://www.drugabuse.gov/PODAT/PODATIndex.html National Institute on Drug Abuse (2006). Principles of Drug Abuse Treatment for Criminal Justice Populations: A Research-Based Guide. Rockville, MD: Author. NIH Publication No. 06-5316. On line at http://www.drugabuse.gov/PODAT_CJ/ Office of Applies Studies. (1995). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). (May 2001). Juvenile Drug Court Program. Department of Justice, OJJDP, Washington, DC. NCJ 184744 Rodriguez, N., & Webb, V. J. (2004). Multiple measures of juvenile drug court effectiveness: Results of a quasiexperimental design. Crime & Delinquency, 50(2), 292-314. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies (2012). National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2009. [Computer file] ICPSR29621-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2012-02-10. doi:10.3886/ICPSR29621.v2. Retrieved from http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/SAMHDA/studies/29621/detail . Scott, C.K. & Dennis, M.L. (2009). Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction, 104, 959-971. Sloan, J. J., Smykla, J. O., & Rush, J. P. (2004). Do juvenile drug courts educe recidivism? Outcomes of drug court and an adolescent substance abuse program. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 29(1), 95-116. Teplin, L.A., Elkington, K.S., McClelland, G.M., Abram, K.M., Mericle, A.A., and Washburn, J.J. (2001). Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiatric Services, 56(7), 823–828. 71