The market, taxation, and redistribution

advertisement

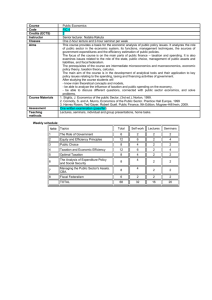

The market, taxation, and redistribution Peter Dietsch, Philosophie, Université de Montréal Presented at the Cérium summer school 2nd and 3rd July 2010 The market, taxation, and redistribution Two central questions: 1) What are the distributive consequences of the international fiscal landscape? 2) To the extent that this landscape generates inequalities we should consider unjust, what institutional responses are called for? Several subsidiary questions: 1) Fiscal systems represent a corrective of the market. What is the justification for the distributive outcome of the market in the first place? 2) How do we justify and implement redistribution? 3) What is the relation between the normative principles of international taxation put forward here and the sovereignty of states? 4) Why not rely on corporations rather than states for a solution? The market as a means of social interaction Two traditional justifications for the market: 1) The maximisation of social welfare but consider: 2nd Best Theorem (RG Lipsey, K Lancaster, “The General Theory of Second Best”, The Review of Economic Studies 24/1 (1956), pp. 11-32) 2) The guarantee of individual liberty but consider: externalities Two insights: 1) The market is contingent on the state 2) The market should be judged by its results (Amartya Sen, “The Moral Standing of the Market”, Social Philosophy and Policy 2/2 (1985), pp.1-19) The distributive outcome of the market Important: Evaluating a distribution requires a theory of justice Justice ≠ Equality Three ways to redistribute: 1) Ex post (eg through income taxation) but: effect on efficiency? 2) Ex ante (eg through estate tax) but: utopian + undermining the rule of law 3) through institutional design (eg through anti-trust policy*) => central to my argument today * (see Peter Dietsch, “The market, competition, and equality”, Politics, philosophy, and economics 9/2 (2010), 213-44) Taxation as a means to redistribute Definition: A tax is a financial duty levied either on the basis of certain economic activities or in virtue of holdings of wealth Objectives: Raising revenue, redistributing income, influencing behaviour, smoothing the economic cycle Some clarifications: 1) Taxation does not conflict with property rights (see Murphy / Nagel, The Myth of Ownership, OUP, 2002) 2) 3) Does taxation imply a conflict with efficiency? When is a tax progressive or regressive? Central questions for today A descriptive and a normative question: 1) What is the impact of tax competition on the distribution of income and wealth both domestically and globally? 2) To the extent that this impact entails injustices, what should we do about it? A definition of tax competition: Interactive tax setting by independent governments in a noncooperative, strategic way Why is tax competition a problem? They undermine the fiscal prerogatives of the state: (1) size of the state & (2) level of redistribution Why is it often ignored by theories of justice? Structure 1) 2) How tax competition works and what its distributive effects are How to regulate it Discussion of two objections: 1) What about sovereignty? 2) Why regulation? Why not rely on socially responsible behaviour of corporations? Various forms of tax competition A multitude of ways to create a favourable tax environment: Lower rates; preferential rates for foreigners (“ring-fencing”); loopholes; regulation (eg bank secrecy) Tax competition (mainly) targets 3 forms of capital: 1) Portfolio capital; eg through low rates combined with secrecy 2) Foreign direct investment (FDI); eg through ring-fencing 3) Paper profits; eg through transfer pricing or thin capitalisation Some figures Estimates for wordwide yearly revenue losses to governments due to individual tax evasion or avoidance: US$ 155 to 255bn “Developing countries are estimated to lose to tax havens almost three times what they get from developed countries in aid.” (Angel Gurria, Secretary-General of the OECD in November 2008) Estimates for the US tax gap by the IRS: US$ 345bn (= 20% of total revenue) At the height of its preferential corporate tax for foreigners, Ireland received 60% of US FDI in Europe 60% of world trade is intra-firm 70% of individual wealth in South America is held offshore The theoretical consequences of tax competition A “race to the bottom”: A sequence of mutual underbidding of capital tax rates, which eventually leads to an under-provision of public goods in all jurisdictions See H.-W. Sinn’s “selection principle”: If the state intervenes to correct for market failure by reintroducing competition between states / systems as the alternative, this alternative will fail, too (H.-W. Sinn, “The selection principle and market failure in systems competition”, Journal of Public Economics 66/2 (1997), pp. 247-74) The empirical consequences of tax competition I For developed countries: 1) Fall in average OECD corporate tax rates and top income tax rates over the last decades 2) Compensated by base broadening (‘tax cut cum base broadening’) 3) More precisely, we see a shift of the tax burden … from multinationals to nationally organised SMEs … from capital to labour … towards indirect taxes … away from high incomes to preserve ‘backstop function’ of personal income tax In sum: Developed countries are able to maintain the size of the budget (1) but only at the expense of compromising the desired level of redistribution (2) The empirical consequences of tax competition II For developing countries: Largely similar impact with two notable differences: The strategy of ‘tax cut cum base broadening’ is usually not open to developing countries Effect of ‘Washington consensus’ Example: Brazil In sum: Developing countries lose both fiscal prerogatives of the state What has been done about it? OECD: Report on Harmful Tax Competition (1998) Several follow-up reports European Union: Code of conduct Savings Directive Discussion of a consolidated corporate tax base G20: Blacklist of tax havens (April 2009) One problem of all these initiatives: Their scope Background justice for international taxation Two approaches to deal with tax competition: 1) A palliative approach focused on distributive outcomes 2) A preventive approach focused on just institutions Two proposed principles: 1) Membership principle: Natural and legal persons should be liable to pay tax in the state of which they are a member. 2) Intentionality principle: Suppose the benefits of a tax policy change in terms of attracted tax base from abroad did not exist, would the country still pursue the policy under this hypothetical scenario? If yes, the policy is evidently not motivated by strategic considerations and therefore legitimate. If not, then the policy is illegitimate. Fitness clubs and free-riding Consider the analogy between a fitness club and a country… Tax evasion and tax avoidance represent forms of free-riding Those who do pay for public services have a legitimate complaint The membership principle (see above) Individuals and companies should be viewed as members in those countries where they benefit from the public services and infrastructure Challenges and implications of the membership principle Challenges: 1) Overcoming differences in the definition of membership 2) Enforcing the principle Implications: 1) For individuals: self-selection into jurisdictions according to political preferences 2) For multinational enterprises (MNEs): real instead of (merely) virtual tax competition The insufficiency of the membership principle Consider two scenarios: 1) Country A lowers a certain tax rate, because this better reflects the political preferences of its citizens 2) Country B lowers a certain tax rate in order to attract capital base from abroad What to say about these changes from the perspective of justice? The intentionality principle (see above) What to make of the intentionality principle? Objective: Delineate (legitimate) fiscal interdependence from illegitimate tax competition. Two observations: 1) Respecting both principles does not lead to tax harmonisation 2) But it does lead to some pressure towards convergence of rates An objection: Is the intentionality principle utopian? Implementation Agreement on rules: Definition of (multiple) residence for individuals; of economic activity for multinationals; adopt Unitary Taxation with Formulary Apportionment instead of Arm’s Length Pricing Reform of current practices: Abolish bank secrecy & preferential tax regimes; make information exchange effective and automatic Enforcement: Creation of a supranational body to provide independent oversight (International Tax Organisation) What about sovereignty? A recent case: US versus UBS Three kinds of sovereignty: (see Stephen D. Krasner, ‘Pervasive Not Perverse: Semi-Sovereigns as the Global Norm’, Cornell International Law Journal 30 (1997) 1) 2) 3) Domestic sovereignty Westphalian sovereignty International legal sovereignty Which of these is / are relevant in the context of tax competition? Conflict between (1) and (2) Sovereignty with strings attached In an economically interdependent world, the notion of Westphalian sovereignty no longer makes sense “… the easy – perhaps, indeed, the obvious – part: establishing that sovereignty (conceptually) must be limited (if it is to be a right). The hard part is actually specifying some concrete limits.” (Henry Shue, ‘Limiting Sovereignty’, in: J.M. Welsh (ed.), Humanitarian Intervention and International Relations (Oxford, OUP, 2004), p. 16) a notion of sovereignty that entails duties as well as rights For a suggestion as to the content of these duties, see above What about CSR*? Different conceptions of CSR: 1) Corporate responsibility beyond the letter of the law 2) Stakeholder theory 3) A market-failure approach Consider a minimalist approach to CSR: Companies have a social obligation to respect the rules of the game laid down by the regulatory framework In particular: Companies have an obligation to pay their taxes Companies have an obligation not to undermine the respect of fiscal obligations * = Corporate Social Responsibility Why even the minimalist conception fails for a manufacturer, adhering to the minimalist CSR may be feasible For the tax planning industry, it seems utopian Who are the tax planners? The ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms; law firms; banks How do they promote tax avoidance? By selling tax advice By creating the legal foundation for the laws, trusts, offshore special purpose vehicles and so on that make tax avoidance possible By promoting bank secrecy Two lessons: lip-service to corporate social responsibility by these companies is hypocritical For them, respecting even a minimalist conception of CSR seems inconceivable Conclusions In order to talk about ‘just taxation’, one needs to talk just as much about taxation as about justice Tax competition undermines the fiscal prerogatives of the state in ways that exacerbate inequalities in income and wealth Tax competition should be limited by two principles – the membership and intentionality principles – to ensure a background justice for international taxation Yes, capitalism is in crisis, but not necessarily for the reasons we often think