Dangerous Patient ()

advertisement

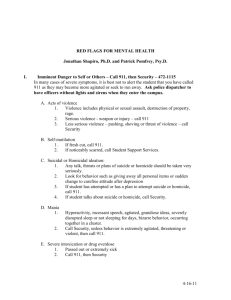

The Dangerous Patient David Mays, MD, PhD dvmays@wisc.edu Predicting Violence • Risk assessment is a field of inquiry with a growing literature over the last 20 years. Predicting violence in potential offenders has been the “Holy Grail” of forensic psychiatry. • Unfortunately, mental health professionals are only a little better than chance at predicting who will be dangerous. Actuarial Data • .Various actuarial instruments have been developed to try to assess violence risk (VRAG, LSI-R, HCR-20, etc.) Their accuracy is better than chance, but not good enough to be of practical use in a clinical setting. Data About Dangerousness • The best data show that patients with the most serious mental illnesses (schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder) are 23x more likely to be assaultive as the general population. (The lifetime prevalence of violence among the mentally ill is 16%, vs. 7% among the general population.) • People who abuse alcohol and other drugs are 7x more likely to be assaultive. Rates of Violence (Fazel S, et al. JAMA May 20, 2009) 30.0% 25.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% Gen pop Schiz Schiz + AODA Violent Individuals in the General Population General Population Violent Nonviolent Violent Individuals in the Mentally Ill Population Mentally Ill Violent Individuals in the Substance Abuse Population Substance Abusers Violent Nonviolent 10 Static Risk Factors for Violence Carlat Psychiatry Report March 2013 • • • • • • • • • • History of violence Male gender Late teens, early 20’s Below average IQ Low socioeconomic status Instability in housing or employment History of property destruction Substance abuse Mental illness Personality disorder (antisocial, borderline) 10 Dynamic Risk Factors for Violence Carlat Psychiatry Report March 2013 • • • • • • • • • • Intoxication Withdrawal Psychotic symptoms Command hallucinations Persecutory delusions Paranoia Physical agitation Verbal aggression Access to weapons Anger (in response to narcissistic injury) Screening Military Veterans (Am J Psych Jul 2014) • The following are related to risk for subsequent violence, and are additive, i.e. combinations of factors have more predictive power. Subjects were followed for 1 year: – Financial instability – Combat experience (witnessing serious injury) – Alcohol misuse – History of noncombat violence or arrest for crime – PTSD + past week irritability A Risky Profile • Young adults with severe mental illness, with trauma and violence in the past, substance abuse in the present, and no interest in treatment in the future. • (In one small study, patient’s own assessment of their risk of becoming violent was a better predictor than two other assessment tools.) Gun Deaths in the USA 1000 12,000 18,000 Suicide Homcide Mass Killing Homicide vs. Suicide • Homicide rates have decreased by half (9.8 – 4.8/100,000) over the last 20 years. Suicide rates have remained the same – 12/100,000. • There are 38,000 suicides per year in the US. There are 14,000 homicides. • 32 college students were murdered at Virginia Tech in 2007. 32 college students died of suicide last week. • 90% of suicides are mentally ill. <5% of murderers are mentally ill. Mental Illness + Guns = Suicide • The strongest link between mental illness and guns is suicide, not homicide. • Homicide is more an urban phenomenon. Suicide is more of a rural phenomenon. • “Means restriction” works for suicide prevention. Ironically, the strongest resistance to means restriction (controlling guns) for suicide is among rural populations. And rural states have the highest suicide rates. Gun Homicide and Mental Illness • Even if we cured all mental illness overnight, the rate of gun homicide would essentially remain the same. What About Mass Shootings? • Mass shootings involve the killing of multiple people, followed by the pre-planned suicide of the shooter(s). Often the victims are strangers. • More often than not, psychological autopsies of these killers describe them as having a mental illness. • 35 states, including Wisconsin, have increased mental health funding in an effort to prevent mass shootings. The $30 Million Wisconsin Plan to Reduce Gun Violence • • • • • • • • Crisis Intervention team training Child psychiatry consultation program Grants to doctors in under-served areas Peer-run respite centers Treatment and diversion Job placement and support Mobile Crisis teams New units at Mendota Mental Health Institute Can We Identify a Potential Mass Shooter? • Possibly, in a few cases. But mass murder is a multi-determined event with no simple preventive solution. They are exceptionally hard to anticipate and avert. Can We Identify a Potential Mass Shooter? • The most likely profile is of a suicidal person who is angry, paranoid, and delusional, with a history of prior violence and substance abuse. Common themes that arise in these murderers is social persecution, envy, and a desire for retribution and revenge. They often seek a theatrical event, so they may videotape themselves, alert an audience on the internet, etc. Anti-Stigma Alert: • In all studies, mental illness is much weaker predictor of violence than: – A history of violence – Substance abuse Risk Factors for Violence • In the early years, parenting factors are the most important risk factor. For teenagers, peer relationships are more important. Mental health problems turn out to be rather poor predictors of future violence. • Conduct Disorder: Conduct disorder first appearing at 6 years old doubles the risk of criminal adult antisocial behavior (71%), compared to those children who first develop conduct disorder at 12 years old. Risk Factors for Violence • Firearms are the single greatest risk factor. 28% of families keep guns at home, 39% are unlocked or loaded or both. • Alcohol - 40% of all 15-24 year old homicide victims are intoxicated. • Bullying/Standby Behavior - 7-16% of schoolchildren are bullied in any given semester. Bullying is worst in rural schools. Bullies are 6x more likely to have a criminal conviction by 24, as well as AODA problems. Victims experience social and emotional isolation. Risk Factors for Violence • Mental illness: up to 60% are diagnosed. Also includes violent preoccupation, chronic humiliation, grandiosity, lack of empathy. ADHD is also linked to adult antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse, although not as strongly as conduct disorder. When combined with conduct disorder, ADHD becomes a more ominous predictor of bad outcome. • Media: controversial, but especially influential in vulnerable children • Families who are dismissive and permissive: too much privacy, parents are afraid of the child. Risk Factors for Violence • Exposure to abuse: 63% of children exposed to domestic violence don’t do well. Violence is related to emotional development (hypersensitivity to anger, difficulties recognizing emotions or complex social roles, less accurate attention to social cues, less ability to generate competent solutions to interpersonal problems), cognitive problems (lower IQ, poor memory and concentration) and children who end up blaming themselves for the violence. Risk Factors for Violence • Peer relationships: One of the most significant risk factors for violence is association with peers whose norms, values and practices are more permissive of criminal behavior. Alternatively, attachment to conventional others, involvement in conventional activities, and belief in the central value system of society hinders juveniles from engaging in delinquent behavior. Subtypes of CD • Childhood onset – Presence of 1 criteria before age 10 – Typically boys exhibiting high levels of aggression, may also be diagnosed as ADHD. – Problems tend to persist to adulthood (33% APD) • Adolescent onset – No criteria met before age 10 – Less aggressive, more normal relationships – Most behaviors shown in conjunction with peers (e.g. gang members) – Less ADHD. Equal gender distribution. – Much better prognosis Limited Prosocial • These youth are less likely to show empathy to others in distress, although they are capable of cognitively recognizing distress in others (unlike some autism). • They are less sensitive to punishment and tend to be thrill-seeking and uninhibited. • These youth are more likely to show both “instrumental” and “reactive” aggression. Reactive Aggression • Reactive aggression is characterized by impulsive defensive responses to perceived provocation. Over-reaction to minor threats is also seen. • Such children may selectively attend to negative social cues, fail to consider alternative explanations for behavior, fail to consider alternative responses, and fail to consider the consequences. • Most reactive aggression is associated with anxiety and depression. Treatment of Reactive Aggression • These youth generally are poorly socialized and have difficulty with emotional modulation: – Deal with hostile-attributional biases and hypervigilance to hostility – Promote self-control mechanisms – Work with managing intense anger – Treat depression and anxiety Instrumental Aggression • In instrumental, or predatory, aggression, violence is used as a means to an end. These youth often show emotional detachment rather than emotional dysregulation. • They do not focus on the negative effects of their behavior on others and resistant to punishment. • Instrumental aggression in pre-adolescence predicts delinquency, violence, disruptive behavior during mid-adolescence, and criminal behavior with psychopathy in adults. • Instrumental aggression is very difficult to treat. Violence and Mental Illness • Very few mentally ill are violent, but studies have demonstrated a small but increased risk of violence for the mentally ill - notably, substance abuse, cluster B personality disorders, psychotic disorders. • Characteristics that are associated with violence: – – – – Impulse control Affect regulation Narcissism Paranoid personality style Violence and Mental Illness • The most seriously violent 5% of psychiatric clients account for half the violence. • Violent and criminal acts attributable to mental illness account for a very small proportion of overall violence. Gender and age are more powerful predictors. The mentally ill are more likely to be victims than perpetrators - 11x higher than nonmentally ill. Their families are more likely to be the targets than unrelated people in the community. Schizophrenia – Actuarial Risk Factors • Past history of violence (forensic release - 50x risk of homicide) • Substance abuse – Risk of homicide is 10x general population – Male schizophrenic AODA 17x – Female schizophrenic AODA 80x • Non-adherence with treatment • Comorbid antisocial personality • Homelessness - 40x violent, 60x attempted murder, 25x murder Schizophrenia – Actuarial Risk Factors • • • • Paranoid cognitive style Hostility and irritability Command hallucinations in some clients Delusions - persecutory, systematized, focused on an individual • The first year after diagnosis Most Recent Study Keers et al. Am J Psych March 2014 • In a longitudinal prospective study of 967 British prisoners incarcerated for a violent offense, it was found that schizophrenia and delusional disorder were not associated with violence after release, unless the patients were untreated. In the untreated group, it appears that violence was associated with the emergence of persecutory delusions. Bipolar Disorder • 25x general population, 49% lifetime prevalence • Impulsivity is prominent, even when clients are asymptomatic. • Clients are often unpredictable: gregarious one moment, hostile the next. • The delusional grandiosity that is often seen in mass murderers implies bipolar mania more than schizophrenia. (Flagrant paranoia may likewise be more the result of a delusional depression than schizophrenia.) Substance Abuse • 12-16x general population • These disorders have the highest correlates to violence, more than all other disorders combined • Impulse control and affect regulation are both impaired by these disorders. • Alcohol is involved in most murders. Drinking more than 5 drinks on any occasion increases the likelihood of violence, either as a perpetrator or victim. • Alcohol is present in >50% of domestic violence, violent crimes, sexual assault, child abuse and neglect. Personality Disorders • Cluster B (borderline, narcissistic, histrionic, antisocial) are the highest risk because of impulsivity and affect dysregulation. Also, narcissistic injury may be an important factor. • Clients with antisocial personality disorder will use violence to intimidate and control other people. • About 75% of prison inmates meet the criteria of antisocial personality disorder. Only 33% of these will be psychopaths. They will have the highest number of criminal charges per year, the most violent crime, be responsible for the most violence in the prisons, and be most likely to recidivate. Boundaries and Personality Disorders • Individuals with personality disorders will try various ways to manipulate the therapist into giving them what they want. Some therapists may be more susceptible to trying to nurture a client who appears needy, leading to boundary violations. Treatment • Results for all forms of treatment for APD are generally dismal. Clients are not usually interested in treatment. Their dishonesty, sensitivity to power issues, and constant manipulating make them poor candidates for therapy. • There is no evidence for the efficacy of any medications. • Other treatments such as milieu, empathy, self-esteem training, or anger management, are problematic or have not shown any consistent benefit. Treatment • Treatment for borderline personality disorder is structured psychotherapy. • No treatments have been carefully studied for narcissism or histrionic personality. Organic Brain Disease • 70% of brain injury clients have aggression and irritability as symptoms. • Frontal Lobe Syndrome • Brief, unplanned, unsustained, ineffectual • These aggressions are triggered by minor episodes, no clear aims or goals, explosive, remorse, long episodes of quiet. • Epilepsy is rarely a cause of planned aggression. Dementia • Dementia invariably involves behavioral disturbances. These may be categorized as non-aggressive verbal (complaining, negativism), non-aggressive non-verbal (pacing, disrobing), aggressive verbal (threats, cursing) or aggressive non-verbal (spitting, kicking, hitting.) The most common disturbances are apathy (36%), depression (32%), and aggression (30%.) Dementia • The evidence for non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions is weak. Historically, antipsychotics have been recommended, but side effects limit their long-term use. Evidence is poor for anticonvulsants or antidepressants. Cholinesterase inhibitors produce conflicting results. Various behavior therapies and environmental modifications are promising, but difficult to implement by families or in most care settings Protecting Yourself • Be alert at work, as when you are safely driving a car • Get hands on training from an expert. Practice screaming fire or 911 • Anticipate how you will react • • • • • • Freeze Flight Fight Fright Faint Psychytachia, tunnel vision/auditory exclusion Responding to Verbal Aggression • Hot Threats • The goal is to talk down the client. Make sure escape route is available, and client can hear and understand you. Overdose with agreement. Don’t argue. Remember body buffer zones. Divide attention by giving choices. Denial is a serious impediment. • Cold Threats • If you feel threatened, it’s a threat. Clients can intimidate by praise or threats. Share your feelings with the team. Meet with the client and tell them how you feel, confront delusions, and go to the police if appropriate. Ignoring threats invites escalation. Staying Safe • Violence due to emotional arousal (anger) is the most common kind in mental health settings. It is easy to recognize anger, and verbal threats are red flags to prepare for violence. You must de-escalate the situation or leave. • When you get up to leave, tell the client what you are doing so it will not be misinterpreted. Don’t block the door. Our Problematic Reactions • Denial – Common defense mechanism in response to fear, even more common in mental health professionals. (We usually turn down our sense of alarm in order to do our jobs.) • Countertransference – Issues that are not well-integrated and are aroused by the client’s behavior. The clinician may act provocatively toward the client, over-control, or ignore the client’s threats. Managing a Crisis MMHI Options Continuum • Anxiety: client is pacing, ignoring others or giving them inappropriate attention – Staff response: • Open, supportive stance at angle to client (feet apart, knees slightly bent, open hands at waist length) • Appropriate personal space with escape route (4-6 feet, more for paranoid, be careful of geriatric client) • Listen and paraphrase empathetically and calmly • Avoid confrontational eye contact • Find out how you can help Managing a Crisis MMHI Options Continuum • Defensive Stage: client begins to act irrationally, challenging authority, intimidating, threatening • Staff response (at least two staff is necessary) • Ready supportive stance (hands open at chest height) • Appropriate distance with escape route (10 feet, 21 feet if client has a weapon) • Set clear, enforceable limits • Remain professional - don’t get provoked • Make sure there is no audience and allow client to vent • Restate limits when client can listen • Present positive options first • If no movement, or client shows pre-attack behavior, disengage to develop a plan. Managing a Crisis MMHI Options Continuum • Aggressive Stage: client loses control and becomes violent • Immediate cues to aggression • • • • • • • • Posture Manner Appearance Voice Verbal abuse or threats Impaired cognition Approach/avoidance “gut” reaction