Barthes and bisto the essentials of theory In the first of a series of

advertisement

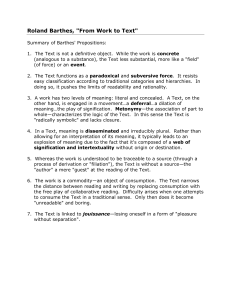

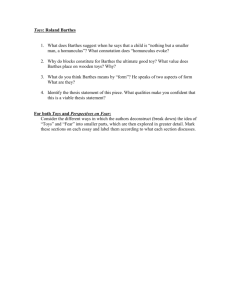

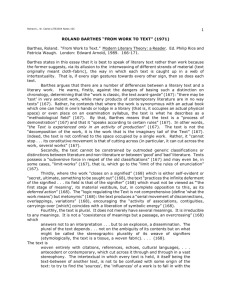

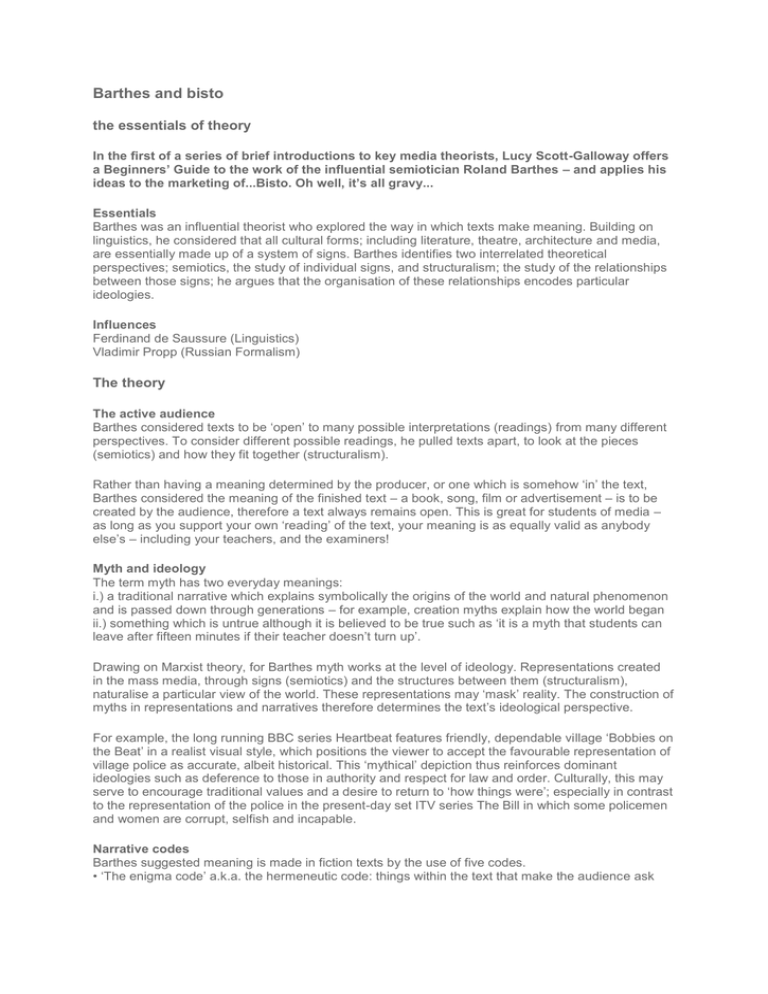

Barthes and bisto the essentials of theory In the first of a series of brief introductions to key media theorists, Lucy Scott-Galloway offers a Beginners’ Guide to the work of the influential semiotician Roland Barthes – and applies his ideas to the marketing of...Bisto. Oh well, it’s all gravy... Essentials Barthes was an influential theorist who explored the way in which texts make meaning. Building on linguistics, he considered that all cultural forms; including literature, theatre, architecture and media, are essentially made up of a system of signs. Barthes identifies two interrelated theoretical perspectives; semiotics, the study of individual signs, and structuralism; the study of the relationships between those signs; he argues that the organisation of these relationships encodes particular ideologies. Influences Ferdinand de Saussure (Linguistics) Vladimir Propp (Russian Formalism) The theory The active audience Barthes considered texts to be ‘open’ to many possible interpretations (readings) from many different perspectives. To consider different possible readings, he pulled texts apart, to look at the pieces (semiotics) and how they fit together (structuralism). Rather than having a meaning determined by the producer, or one which is somehow ‘in’ the text, Barthes considered the meaning of the finished text – a book, song, film or advertisement – is to be created by the audience, therefore a text always remains open. This is great for students of media – as long as you support your own ‘reading’ of the text, your meaning is as equally valid as anybody else’s – including your teachers, and the examiners! Myth and ideology The term myth has two everyday meanings: i.) a traditional narrative which explains symbolically the origins of the world and natural phenomenon and is passed down through generations – for example, creation myths explain how the world began ii.) something which is untrue although it is believed to be true such as ‘it is a myth that students can leave after fifteen minutes if their teacher doesn’t turn up’. Drawing on Marxist theory, for Barthes myth works at the level of ideology. Representations created in the mass media, through signs (semiotics) and the structures between them (structuralism), naturalise a particular view of the world. These representations may ‘mask’ reality. The construction of myths in representations and narratives therefore determines the text’s ideological perspective. For example, the long running BBC series Heartbeat features friendly, dependable village ‘Bobbies on the Beat’ in a realist visual style, which positions the viewer to accept the favourable representation of village police as accurate, albeit historical. This ‘mythical’ depiction thus reinforces dominant ideologies such as deference to those in authority and respect for law and order. Culturally, this may serve to encourage traditional values and a desire to return to ‘how things were’; especially in contrast to the representation of the police in the present-day set ITV series The Bill in which some policemen and women are corrupt, selfish and incapable. Narrative codes Barthes suggested meaning is made in fiction texts by the use of five codes. • ‘The enigma code’ a.k.a. the hermeneutic code: things within the text that make the audience ask themselves questions about what will happen. The answers to the questions can be found by consuming the text. For example, will Charlie Bucket find a golden ticket? • ‘The events and actions code’ a.k.a. the proairetic code: each action and event within a text can be linked to nameable sequences operating in the narrative. Barthes asserts that each effect could be ‘named’ giving a series of titles to the text. These are often made very explicit on the DVD casing – the chapter titles are generally based on events or actions. • The symbolic code: the process of representing an object, idea or feeling by something else. For example, a fence between two characters may symbolise their emotional distance. Some have suggested that the infamous ‘adrenaline shot’ in Pulp Fiction is the symbolic penetration of Mia by Vince. • The semic code: refers to the use of connotation to give the audience an insight into characters, objects or events. For example, conventional car advertisements feature the car in an open, green landscape. The connotations created by the setting are of freedom and escape. • The cultural code concerns all the culturally specific knowledge used to make meaning in a text. For example, the Coronation Street title sequence features stereotypically ‘northern’ streets and houses, connoting traditional communities and family values. The audience must be familiar with such northern typification to associate particular meanings with the text. Applying Barthes’ narrative codes to Bisto The latest ad for Bisto features a montage of shots of ‘ordinary’ people of all ages, races and both genders, willingly taking ‘the pledge’ to eat dinner with their family, at the table, on one night a week (see page 61). If we deconstruct the ad into its various signs, we have many units of meaning: • the people being represented • the settings they are represented in • their dialogue, costumes, hairstyles and accents. If we deconstruct it further, we might consider the lighting used in each shot, the shot types and angles used, the composition of each shot and the non-diegetic music. The creative team behind the advert chose to represent the following. • The people: a young boy, a young girl, a group of teenage girls, a group of teenage boys, four men at work, and one thirtysomething woman. • The settings: a northern street with a brass band, a windy farm, a train station, a residential street with high rise flats in the background, a street, a street corner, a kitchen. • The media language: close-ups, mid-shots, long-shots, brightly lit, dimly lit, shallow focus, deep focus. Having broken the ad down into its constituent signs, semiotically the preferred reading is that the product, Bisto, can appeal to a demographically varied target audience, as long as you value family. Structurally, it is interesting to note the combinations of signs chosen; for example the young girl is white, on a windy farm, in a close up. The group of teenage girls are black, in school uniforms on a street corner. The group of teenage boys are white, dressed in ‘skater’ style and sitting on a step in the street. The thirtysomething woman is Asian, smartly dressed, set in a rural street in a medium shot. One of the men is Asian, in a suit, in a work environment; whereas the other three are white, in overalls and in factory-like settings. Each shot utilises the semic code; a connotation of high rise flats is of inner city, working class families, the connotations of the men’s hardhats is of blue collar occupations. The cultural code is also useful in deconstruction; as intertextually the mise-en-scène of the ad reminds us of similarly northern-set advertisements such as Hovis and Werthers Originals, and drawing on the audience’s cultural recognition the cobbled streets of the shot with the brass band evoking a sense of working class community spirit and tradition. Such combinations of signs have connotations that work both to challenge and reinforce stereotypes; the Asian woman looks wealthy, as does the Asian man, but the ‘disaffected black youth’ is still hanging out on a street corner. ‘Mothers’ are noticeably absent from the paradigm of representations, presumably because they are at home cooking with Bisto, waiting for their families to keep their promise and come home for dinner; whether they do so remains an enigma. Quotable Quote The death of the author is the birth of the reader The Death of the Author, 1968 • Barthes argued that meaning is not exclusively made by the author or producer of a media text but by the reader or the individuals who make up the audience of a media text. Worth a visit to the library... In this volume of essays, Barthes explores the way signs function in cultural contexts to make meanings that contribute to the maintenance of contemporary social life. Essays are based on contexts drawn from popular culture, films, advertising, magazines, cars, children’s toys and hobbies. An introduction to Barthes’ critical theory with lots of cartoon pictures. Did you know? Although he didn’t say so in public until his later life, Barthes was gay, and some therefore consider him an early thinker for queer theory. Lucy Scott-Galloway This article was first published in MediaMagazine 16. Glossary Semiotics: The study of signs Sign: A unit that makes meaning Structuralism: Approach to media analysis which borrows its principles from linguistics (the study of language). Structuralism considers the relationships (structures) between signs to be more important than what a sign may mean on its own. Paradigm: A group of similar signs from which a selection is made to make a text (i.e. a selection may be made between a paradigm of colours, a paradigm of fonts, and a paradigm of sizes to produce red point 12 typography in Times New Roman). Syntagm: The combination of signs selected from different paradigms. In the example above, red point 12 typography in Times New Roman is a syntagm. Icon: A sign which visually corresponds to that which it represents. A rainbow may be an icon of a range of colours. Index: A sign which refers in some way to that which it represents. A rainbow may be an index of new beginnings, as in nature they are generated when the sun comes out after the rain. Symbol: A sign which is used to represent something to which it bears no logical relationship. For example, there is no reason why green should symbolise jealousy. A rainbow may be symbolic of hope. Myth: Artificial representations and invalid beliefs about society that circulate in cultural products, such as the mass media.