Rapid Physicochemical Profiling as an Aid to Drug Candidate

advertisement

UK QSAR Symposium at Syngenta

'Rapid Physicochemical Profiling'

Derek P. Reynolds

25th April 2001

Physical Chemistry Team

Christopher Bevan, Alan Hill, Klara Valko, Pat McDonough

Chemical and Analytical Technologies Department,

GlaxoWellcome R&D,

Stevenage, UK

Turning Hits and Leads into New Medicines

GlaxoWellcome has funded a worldwide project to deliver high throughput

screens for Physicochemical, Pharmacokinetic, Metabolic, and

Toxicological Factors

OBJECTIVES:

– High-throughput to screens support discovery projects

– A large international repository of consistent data which can help us

learn more about fundamental mechanisms regulating kinetics and

toxicology

– Construction of predictive models which aid the design of drugs

Screens Available

Physicochemical Screens

– Lipophilicity (CHI)

– Solubility

– pKa

ADME

– In-vitro metabolism (Liver Microsomes)

– Permeation (MDCK)

– In-vivo pharmacokinetics - (Cassette Dosing)

Genetox

– SOS gene, umuC mutagenicity assay

Analysis Tools

– Calculated properties

– Modeling

The Physicochemical Properties of a Drug

have an important influence on its

Absorption and Distribution in-vivo

Predictive models aid drug design

however

models are built on real data and novel

compounds often need new rules!

Comparison

Measured logD (x axis) and clogD (y axis)

octanol/water pH 7.4

Measured vs c logD s for 434 compounds

y = 1.0926x - 0.6948

2

R = 0.4075

8

6

4

2

0

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

-2

-4

-6

-8

1

2

3

4

Part 1

Experimental Methods for Measurement of

Lipophilicity, pKa, and Solubility

Part 2

Using Physicochemical Data to Understand

Biological Data. An Example:

Intestinal Absorption of Drugs

What is high-throughput ?

Is it:

high total numbers?

speed of measurement?

rapid response?

lower total cost?

lower cost per sample?

accurate?

flexible?

‘Toolkit’ of High Throughput Methods for

lipophilicity, solubility, and pKa

Standardised general methods suitable for libraries and large compound

sets (deployed globally)

Rapid response ‘open-access’ versions for ‘immediate answers’ and project

specific investigations

Automated versions of classical determinations e.g. octanol logD

Over 17,000 accurate determinations of lipophilicity, solubility, and pKa

made by GW in the UK over the last 12 months

Some methods now developed are suitable for deployment alongside invitro biological screens

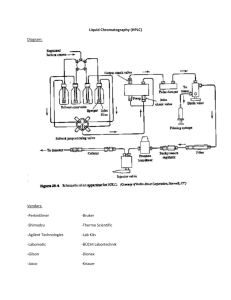

Fast Generic Gradient HPLC:

The basis for high throughput characterisation, purification, and property

determination of new compounds and libraries

For details see:

‘Separation Methods in Drug Synthesis and Purification’

Ed. KlaraValko, Elsevier, October 2000

Relevant Chapters:

Fast generic HPLC methods- I.M.Mutton

Coupled chromatography-mass spectrometry techniques for the analysis of

combinatorial libraries- S.Lane

The development and industrial application of automated preparative HPLCT.Underwood, R. Boughtflower and K.A. Brinded

Measurements of physical properties for drug design in industry- K. Valko

Fast Generic Gradient HPLC as a basis for

Physicochemical Property Measurement

Advantages:

Fast, accurate and automation friendly

Can analyse DMSO solutions directly

Tolerant of impure compounds

Compatible with MS for identity confirmation

Options for Lipophilicity Measurement

logD measurement by automation of the classical

partition experiment. Solute concentration measured by

gradient HPLC

HPLC retention time as a measure of lipophilicity

Octanol/Water LogP Determination

The aqueous phase can be sampled through the octanol phase

without cross-contamination

Analysis:The samples and blanks are analysed using either an

HP1050 or HP1100 HPLC system using a fast generic gradient.

Generic Gradient HPLC ( ‘Five minute CHI method’)

LunaC18(2) 50 x 4.6 mm; 2.00 ml/min; Mobile phase A 50 mM ammonium acetate pH 7.4 and B is 100% acetonitrile. Gradient: 0 - 2.5

min 0 - to 100% B; 2.5 - 2.7 min 100% B.

C om pound

T heophylline

Phenyltetrazole

B enzim idazole

C olchicine

Phenyltheophylline

A cetophenone

Indole

Propiophenone

B utyrophenone

V alerophenone

C H I 7.4

at pH 7.4

18.4

23.6

34.3

43.9

51.7

64.1

72.1

77.4

87.3

96.4

C H I2

at pH 2

17.9

42.2

6.3

43.9

51.7

64.1

72.1

77.4

87.3

96.4

C H I 10.5

at pH 10.5

5.0

16.0

30.6

43.9

51.7

64.1

72.1

77.4

87.3

96.4

Calibration of CHI at pH 7.4

120.00

y = 54.329x - 71.702

2

R = 0.9972

100.00

80.00

60.00

40.00

20.00

0.00

1.4

1.9

2.4

2.9

3.4

CHI - Chromatographic Hydrophobicity Index

A measurement for the Pragmatist not the Purist !

CHI is an HPLC retention index derived from retention time in a gradient

HPLC run and scaled using a set of standard compounds

Provided the same stationary phase and mobile phase are used, then CHI

for a given compound should be a reproducible measure of lipophilicity

(independent of equipment, operator, or laboratory)

CHI is essentially a solvent strength parameter (scaled to approximate to

the % organic concentration in the mobile phase when logk=0)

CHI = f (logkwater , logkorganic )

Where: logkwater =retention factor extrapolated to pure water

logkorganic = retention factor extrapolated to 100% organic

General Solvation Equation

logSP = Solute Property, i.e., property of a series of solutes

in a given phase system, e.g., logP, logBBB,

logk, CHI, etc

logSP = c + e.E + s.S + a.A + b.B + v.Vx

The coefficients

c, e, s, a, b, and v

are specific to each

Solute Property

Equations are robust and apply

to molecules in their unionized

state. Correlation coeffs R >

0.90 for most processes

Descriptors are specific to each

molecule, where:

E = Excess Molar Refraction

S = Polarisability

A = Hydrogen Bond Acidity

B = Hydrogen Bond Basicity

Vx = McGowan Volume

SOLVATION EQUATIONS FOR CHI

CHI = C + v(e’ E + s’ S + a’ A + b’ B + Vx)

E - excess molar refraction term, normalised to alkanes

S - solute dipolarity/polarisability descriptor

A - solute hydrogen bond acidity descriptor

B - solute hydrogen bond basicity descriptor

Vx - McGowan characteristic volume

Systems

LogPhexadecane

CHIACN

CHIMeOH

LogPoct

CHIIAM

v

4.5

65

50

3.8

50

e

0.15

0.1

0.1

0.15

0.15

s

-0.35

-0.25

-0.2

-0.25

-0.15

a

-0.8

-0.35

-0.15

0.0

0.1

b

-1.1

-1.0

-0.85

-0.9

-1.0

Equations are robust and apply to molecules in their unionised state.

Correlation coeffs R > 0.95

Measurements of molecular descriptors via retention

data from several diverse HPLC systems

We can set up solvation equations for various reversed-phase HPLC

partition systems.

Knowing the regression constants for the HPLC systems, the molecular

descriptors can be derived by iterative fitting from the retention data of

the solute.

Selected HPLC systems

Luna C-18 column with acetonitrile gradient (CHIACN)

CHIACN = 7.1 + 0.41E - 1.06S - 1.59A - 4.88B + 4.8Vx

Luna C-18 column with trifluoroethanol gradient (CHITFE)

CHITFE = 6.9 + 0.67E - 1.96S - 3.1A - 3.94B + 5.67Vx

Polymer C-18 column with acetonitrile gradient (CHIPLRP)

CHIPLRP = 8.19 - 0.41E - 0.44S - 2.50A - 5.64B + 4.38Vx

DevelosilCN column with methanol gradient (CHICN-MeOH)

CHICN-MeOH = 3.93 + 0.79E - 1.05S - 0.72A - 4.5B - 5.42Vx

DevelosilCN column with acetonitrile gradient (CHICN-AcN)

CHICN-AcN = 5.67 + 0.2E - 0.28S - 0.55A - 4.15B + 3.68Vx

Fluorooctyl column with trifluoroethanol (CHIFO-TFE)

CHIFO-TFE = 7.45 - 0.12E - 0.57S - 3.67A - 1.89B + 3.11Vx

Lipophilicity and Solubility are pKa-dependent

Lipophilicity v pH profiles are needed to fully understand partition

behaviour

pH cannot be properly controlled in the CHI experiment because of the

organic modifier. Ionisation can be suppressed with buffer additives to give

reliable CHIN values (I.e. CHI lipophilicity of the neutral form of the

molecule)

A rapid method for pKa determination is needed to allow the computation

of lipophilicity v pH profiles

Gradient Titration: a faster way to measure pKa

values

Prototype instrument developed by Alan Hill at GlaxoWellcome Research

(Stevenage, UK)

Collaboration with Sirius from 1997 to develop instrument.

First Sirius commercial instrument now in routine use at Stevenage

The Team:

GlaxoWellcome: Alan Hill*, Chris Bevan*, Derek Reynolds*

Sirius: John Comer, Brett Hughes, Karl Box, Kin Tam, Roger Allen, Simon

Thomson, Paul Hosking

*GT inventors; Patent applied for (WO99/13328)

A faster way to measure pKa values

The goal:

– >96 samples per day

– pKa measurement between pH3 and pH11

– automatic dilution: samples in DMSO solution in microtitre plates

– Easy to use and suitable for ‘open-access’ operation

A new instrument

– Sirius Gradient Titrator for pKa measurement

– Spectroscopic measurement technique

– Commercial instrument launched 1Q 2000

Sirius pKa Profiler

Calibrating GT with standard compounds

Calibration Curve for Standard pKa Values

12

y = -0.0653x + 12.394

abs x10+2

R2 = 0.9959

0.02581

10

0.01595

0.00609

8

pH

-0.00377

-0.01363

6

-0.02349

0

-0.03336

-0.04322

4

-0.05308

30.0

41.5

53.0

64.5

76.0

87.5

99.0

110.5

100

110

122.0

133.5

2

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

120

130

145.0

P oints

140

150

Time (secs/2)

Benzoic acid

Phthalic acid

Nitrophenol

Chlorophenol

Phenol

pKa 3.978

pKa 4.843

pKa 6.973

pKa 9.240

pKa 9.796

Five standards. First derivative peak

maxima correlated with pH-metric

pKa values (25°C, I = 0.15M).

Standards can be mixed for rapid

calibration. Time (seconds) is

proportional to pH.

What are suitable measurements for

physicochemical screening?

Lipophilicity and pKa are valuable for compound selection- but there are not

usually any absolute pass/fail criteria

Lipophilicity is essentially a composite parameter which reflects the

properties of both the polar surface and the hydrophobic surface of a

molecule. Descriptors which are derived from several partition systems will

be more likely to yield general QSAR relationships

Aqueous solubility depends on specific packing and intermolecular

interactions in the solid as well as on the properties and ionisation state of

the molecule in solution- For some drug targets (e.g. related to arachidonic

acid cascade or fatty acid metabolism) then low solubility of leads may be a

general issue that may require a solubility screen

Options for Solubility Measurement

Solubility measurement by equilibration of solid sample with buffer.

After filtration the solute concentration is measured by gradient

HPLC. Sample preparation is rate limiting (20 per day)

Precipitation by dilution of concentrated DMSO solution. After

filtration the solute concentration is measured by generic gradient

HPLC. Can be automated (96 well plate per day)

Precipitation by dilution of concentrated DMSO solution. Detect

appearance/disappearance of precipitate by nephelometry. The

introduction of microtitre plate nephelometers makes this suitable

for use by biochemical screening groups (Many plates per day)

Solubility by Laser Nephelometry

The laser nephelometer used is the NEPHELOstar (BMG LabTechnologies Offenburg, Germany). This

instrument is a forward scattering Laser-Nephelometer employing a polarised laser diode that lases in

the red at 635 nm. The Laser beam is passed through the well in a vertical and concentric path as

shown below: Forward scattered light is measured beneath the well.

References:

1. C. D. Bevan, R. S. Lloyd, Anal. Chem. 72 (2000) 1781.

Solubility by Laser Nephelometry

Procedure:

Compounds are supplied as 10 mM solutions in DMSO in 96 well microtitre plates. These are initially

diluted 20 times with aqueous buffer to give a 5% DMSO/aqueous buffer solution. Then stepwise serial

dilutions are made with 5% DMSO/aqueous buffer until precipitated compounds just redissolved. These

dilutions are then monitored nephelometrically.

This technique is able to reproducibly detect turbidity in suspensions and distinguishes them from true

solutions.

The method is non-destructive and simple and uses procedures very similar to those used for

determination of dose response curves in biochemical assays. It is easy to integrate in a high

throughput drug screening process.

AUTOMATING THE DETERMINATION OF AQUEOUS DRUG

SOLUBILITY USING LASER NEPHELOMETRY IN MICROTITRE

PLATES

David Proudlock*, Malcolm Willson, Barbara Carey, Glaxo Wellcome R&D Medicines Research Centre, Stevenage UK

Three pieces of equipment were required for plate handling, reagent addition and measurement.

They were:Zymark Twister, Labsystem Multidrop, BMG Nephelostar

Summary: Measurements that characterise the properties

of molecules are now readily available

Conventional measurements (octanol partition and solubility) can be

automated to some degree

Rapid gradient HPLC retention times can be converted into a reliable index

of lipophilicity (CHI)

HPLC at extremes of pH provide a convenient way to determine the

lipophilicity of the unionised form of acids and bases (CHIN)

CHIN values from HPLC systems with different selectivity characteristics

can be combined to determine molecular parameters that define solute

polarity and H-bonding (S, A, B)

A new type of titration (gradient titration) provides rapid pKa measurement

Solubility can be rapidly estimated alongside biological screening by using

a microtitre plate based nephelometer

Measured pKa values can be combined with single point solubility or

lipophilicity determinations to calculate pH profiles

Part 2

Using Physicochemical Data to Understand

Biological Data. An Example:

Intestinal Absorption of Drugs

What should we use physicochemical profiles for?

Comparison with calculated properties

Derivation of both general and project specific QSAR models

Selection of physico-chemically diverse molecules for biological

investigation (in vitro and in-vivo)

To provide insight into the mechanisms of biological partition and in-vivo

transport processes

What about ‘Biomimetic’ measurements?

(e.g. Membrane affinity, Serum albumin binding,

Cell Permeability)

Do they predict in-vivo properties better than

‘classical’ measurements?

(e.g. logP, solubility, pKa)

Provide additional rather than alternative

information

High-throughput permeability screens?

CACO2 (e.g Artursson et. al.)

MDCK

PAMPA (Kansy et. al., Hoffman-La Roche)

Alkane/Water membranes (Wohnsland and Faller, Novartis)

Simplistic interpretation of data can be misleading. All are potentially

valuable when used systematically to help in the understanding of

biologically relevant mechanisms of action.

Affymax MDCK permeability screen (Lori Takahashi)

COS: Components & Assembly

Top Block

Base Block

Seeded Transwell

Figure 1. The COS system is an in-vitro assay apparatus utilizing a single

sheet of cultured epithelial cells sandwiched between an array of loading

wells on the apical side and a complementary array of receiving wells on the

basolateral side. The construct allows for the collection of in-vitro Papp data

with greater throughput, consistency, and reproducibility over the traditional

Transwell™ apparatus.

Predicting Human Oral Absorption

(Plot of Human Intestinal Absorption v MDCK Cell Permeability)

120

100

HIA %

80

60

40

20

0

1

10

50

100

MDCK Papp (nm/sec)

1000

Model for MDCK cells

based on CHI values

logP app MDCK = 0.0372CHI(MeOH) - 0.227 cMR -0.78Ind (acid) + 1.659

Predicting Human Oral Absorption

(Model includes measured lipophilicity and calculated molecular size)

% Human Oral Absorption = 1.31 CHI(MeOH) -10.93cMR + 88.6

n=52 r=0.81 s=19.7 F=15.9

% absorbed drug

140

120

P re d ic t e d

100

80

60

40

20

0

5

25

45

65

M e as u r e d

85

105

Solvation equation for oral absorption

% Abs = 92 + 2.9E + 4.1S - 21.7A - 21.1B + 10.5Vx

n=170 r2=0.74

sd=14%

Note that the relative size of the v coefficient is smaller than for

water/solvent partitions.

The e and s coefficients are insignificant

Absorption is generally high (90%) unless several H-bond donor/acceptor

groups on a molecule decrease absorption. The equation is not affected by

whether a compound is acidic or basic

The equation is consistent with other models e.g.

– polar surface area (Palm and Clark)

– CHI - CMR

– logD v CMR

Advantages of Abraham QSAR Models

% Abs = 92 + 2.9E + 4.1S - 21.7A - 21.1B + 10.5Vx

n=170 r2=0.74

sd=14%

Solute parameters can be estimated from molecular structure fragments or

derived from experimental partition measurements

– Allows prediction drug behaviour prior to synthesis and a test of the

model after synthesis by accurate physicochemical property

measurement

The same parameters are always used so that different systems can be

directly compared

– Can be used to investigate molecular mechanisms

Prediction of Human Intestinal Absorption from the Solvation Equation

% Abs = 92 + 2.9E + 4.1S - 21.7A - 21.1B + 10.5Vx

100

80

Training set

Predicted

60

Drugs 229-241

40

Low solubility

20

Dose dependant

0

-20

0

20

40

Observed

60

80

100

Solvation equation for oral absorption

% Abs = 92 + 2.9E + 4.1S - 21.7A - 21.1B + 10.5Vx

n=170 r2=0.74

sd=14%

Comparison with other processes

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127, r2 = 0.80, SD = 0.29, F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

A very different equation when compared to:

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127 r2 = 0.80 SD = 0.29 F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

This does not fit a partition model of membrane

transport (e.g. octanol/water)

logkoct = 0.088 + 0.562 E – 1.054 S + 0.034 A - 3.46 B + 3.814 Vx

A very different equation when compared to:

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127 r2 = 0.80 SD = 0.29 F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

A very different equation when compared to:

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127 r2 = 0.80 SD = 0.29 F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

Solvation equation for rate of uptake into C18 extraction disc

logkup = -5.34 + 0.08 E + 0.20 S - 0.08 A - 0.28 B + 0.33 Vx

n=21 r2=0.95

sd=0.08 F=30

A very similar equation to:

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127 r2 = 0.80 SD = 0.29 F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

Cell Permeability Models

logPapp (CaCo2) = - 4.4 - 0.20 E + 0.26 S - 1.27 A - 0.24 B + 0.09Vx

logPapp (MDCK) = 4.3 + 0.10 E + 0.19 S - 1.73 A - 0.79 B - 0.17Vx

Similar but not identical to:

A pseudo-rate equation can be derived from the equation for %of Absorbed Dose

log{ln[100/(100-%Abs.)]} = 0.54 - 0.025 E + 0.14 S - 0.41 A - 0.51 B + 0.20Vx

n = 127 r2 = 0.80 SD = 0.29 F = 94

Zhao YH, Le J, Abraham MH, Hersey A, Eddershaw PJ, Luscombe

CN, Butina D, Beck G, Sherborne B, Cooper I, Platts,J.A.. J Pharm Sci.,

submitted

Wohnsland and Faller, J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 923 - 930

Artificial Alkane/Water Membranes

Figure 4 pH-dependent permeability of ionizable compounds: (a) diclofenac (acidic pKa = 4.0),

(b) desipramine (basic pKa = 10.6), and determination of their permeabilities through the

unstirred water layer: (c) diclofenac; (d) desipramine.

Wohnsland and Faller, J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 923 - 930

Artificial Alkane/Water Membranes

They analyse their data based on two transport processes that contribute to

effective measured membrane permeability Pe (I.e. Intrinsic membrane

permeability Po and permeability through an unstirred water layer Pul)

Relative contributions from Po and Pul were deduced from pH Permeability profiles

and using literature values for aqueous diffusion coefficients, they estimate the

thickness of the unstirred layer

They demonstrate that intrinsic permeabilities are directly proportional to the

alkane/water partition coefficients

The estimated thickness of the unstirred layer in their model was 300mm and they

quote estimates of 1500mm in the CACO2 model and 50mm in-vivo in the GI tract

Are their assumptions correct? They ignore diffusion across the interface and

assume that diffusion rates are the same for all molecules

Mechanistic Inferences from the Different Data

Types

The different types of information (measured properties, experimental

permeability models, and calculated Abraham parameters) are consistent

with the idea that human intestinal absorption and permeability models

involve similar processes

Diffusion across the membrane interface (across the unstirred water layer?)

is often the step that controls the overall permeability

Molecular diffusion rates and interfacial transfer rates are significantly

slowed by the presence of polar functionality and hydrogen bonding

interactions but appear to be relatively insensitive to ionisaton of acidic and

basic groups

General empirical QSAR models for intestinal absorption are possible based

on a diffusion controlled process. They will produce high estimates when

other mechanisms become rate limiting (e.g. solubility and dissolution,

active efflux, low intrinsic membrane affinity)

Where to next? What should we measure?

Direct measurement of diffusion rates of molecules (in free solution and at

interfaces)?

– What are the QSAR relationships (e.g. Abraham Solvation Equations)?

Overall bioavailability (I.e.not just intestinal absorption) is the key parameter

in candidate selection. In general increasing lipophilicity of drugs tends to

increase their susceptibility to metabolism

– What are the specific QSAR relationships for partition and rate of uptake

into liver? What would this tell us about the mechanisms of uptake and

penetration to the sites of metabolism?

Collaborators and Co-workers

University College London

– Mike Abraham, Chau My Du, James Platts, Yuan Zhao, Joelle Le

BMG LabTechnologies

– Derek Patton, Monika Siggelkow

Sirius

– John Comer, Brett Hughes, Karl Box, Kirsty Powell, Kin Tam,

Paul Hosking, Roger Allen, Lynne Trowbridge, Colin Peake

GlaxoWellcome

– CLOP- Mike Tarbit, Om Dhingra, Mark Patrick, Lori Takahashi

– Rachel Thornley, Anne Hersey, Darko Butina, John Hollerton,

Keith Brinded, Ian Mutton

– Chris Bevan, Alan Hill, Klara Valko, Pat McDonough