Chapter 13

advertisement

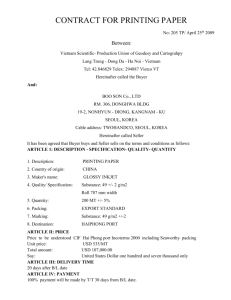

Chapter 13 Shipper Process INTRODUCTION • The focus of this chapter is on implementation and execution of this transportation management strategy • the day-to-day shipper activities required to manage the domestic and global transportation process DOMESTIC TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT PROCESS • Figure13.1 provides an overview of the domestic transportation management process that shippers utilize. Shipment Source • The starting point in the transportation management process is either the customer order or purchase order – inbound or outbound. • The customer service, sales, or marketing departments are charged with the responsibility of receiving and processing the customer’s order. • via mail, phone, fax, EDT, or the Internet. Shipment Source • Associated with the customer order and purchase order are the underlying terms of sale agreed to between the buyer and seller. • The terms of sale indicate who has control over the selection of the carrier, who pays the transportation freight bill, and where title to the goods pass from the seller to the buyer. • Essentially, the terms of sale define the buyer and seller transportation role in the sales transaction. Shipment Source Figure 13.2 shows some typical domestic terms of sale. The free on board (FOB) domestic terms of sale have a: • named point that determines where title passes to the buyer, • where responsibility for selecting and routing the shipment passes to the buyer, and • where the buyer begins paying for the transportation charges. Shipment Source • For example, the FOB-delivered term of sale states the seller pays the freight charges to the buyer’s door, the seller selects the carrier and routes the shipment, and title passes to the buyer upon delivery to the buyer. • The latter point means the seller has title to the goods during transit and bears the responsibility for filing claims for transportation loss and damage. Shipment Source • The FOB-origin term of sale means the buyer incurs all transportation responsibility, cost, and claim responsibility. • The seller is responsible for making the shipment available at the seller’s door for the carrier that the buyer selects. • The buyer selects the carrier, routes the shipment, pays the carrier, and assumes the responsibility for claims. • The FOB-origin term of sale is used in purchasing of materials to enable the buyer to gain control over the cost and service of inbound transportation. Shipment Source • The FOB-Port of Entry term means the seller incurs all transportation responsibility up to the port of entry and the buyer assumes the responsibility from the Port of Entry to destination. Shipment Source • the terms of sale used to sell and buy products determines the level of transportation control exercised by the buyer and the seller. • If a firm buys all raw materials on an FOBdelivered basis and sells on an FOB-origin basis, the firm would have minimal transportation management responsibility. Shipment Source • Today, many firms attempt to increase the amount of transportation management control by buying FOB-Origin and selling FOBdelivered. • By using these two terms of sale, the firm can maximize its control over the cost of its products. Shipment Analysis • The shipment analysis function examines the specifics of the shipment, service levels required, packaging, rates, and consolidation. • The shipment specifics come directly from the customer and purchase order, and define the product to be shipped, the quantity, the origin, the destination, the consignee, pickup and delivery dates, routing instructions, and delivery requirements. Shipment Analysis • Figure 13.3 provides an example of the shipment specifics needed to effect the transportation of a customer or purchase order • The information in Figure 13.3 provides all the information needed for the scheduling of a carrier. Shipment Analysis • The service level requirement is often the company’s stated delivery policy. • EG: 5 business days; 3 business days; expedited delivery – next day; 99 percent of the shipments will be delivered within 3 days Rate Analysis • The transportation manager examines the cost of alternative shipment methods to accomplish the move with the desired service level. • In this section the freight cost is analyzed for alternative transportation methods and the accompanying rates. Rate Analysis • It is often cheaper to use an express carrier rather than an LTL carrier for shipments weighing less than 400 pounds (200 kg). • The carrier selection decision will be based on the level of service required and the consistency of the carrier’s service. Rate Analysis • Another rate analysis that considers the size of the shipment examines the cost of shipping the product via LTL or using a TL carrier. Figure 13.5 Shipment Specifics Origin: Polakwane Destination: Richards Bay Weight: 7000 kg Charges as LTL Shipment Distance: 1400km Charges with Truckload Carrier LTL Rate = R490 per 100kg Rate = R9 per km Discount = 45% Distance = 1400km Effective LTL Rate = R220.50 Charge = 1400km @ R9 per km Charge = 100kg @ R225.50 =R15435 =R1260 Rate Analysis • With zone skipping, the shipper, using a consolidator, bundles numerous shipments destined for a city, moves the bundled quantity to the postal system near the destination city, and the postal service delivers the packages to the respective consignees. Carrier Scheduling • The objective of carrier scheduling is to arrange for a carrier to meet the shipper’s transportation cost and service goals contained in the carrier selection decision. • As indicated in Figure 13.1, the carrier scheduling techniques include core carriers, routing guides, approved carrier list, and intermediaries. Carrier Scheduling • The core carrier concept is based on the principle of leveraging business volume to obtain desired cost and service. • Shippers develop a number of core carriers, anywhere from 3 to 20 carriers, that are the prime providers of transportation service. • These core carriers typically realize over 90 percent of the shipper’s annual freight expenditure and are the first carriers the shipper contacts when there is a load to be moved. Carrier Scheduling • Both the core carrier and the shipper are dependent on the other: the shipper relies on the core carrier to move the loads and the core carrier relies on the shipper for a major source of its revenue. • Depending on the number of core carriers a shipper is using, the loss of one core carrier may result in a significant disruption of service to customers, plants, and warehouses. • The greater the portion of revenue coming from one shipper, the more dependent the carrier is on the shipper. Carrier Scheduling • To attain this carrier leverage across a large vendor base, companies utilize a routing guide that tells the vendor to use a carrier from a list of specified carriers. • The routing guide is a matrix that tells the shipper which carrier to use for a given transportation link and focuses the inbound freight on a limited number of carriers. Carrier Scheduling • Figure 13.7 is an example of an LTL routing guide. • The routing guide is a quick reference to which carrier should be used for inbound and outbound moves between particular states. • The carriers identified in the cell are the leastcost, best-service core carriers to use over the transportation link. Carrier Scheduling • Figure 13.7 shows that for a movement from Ohio to New York the carrier of choice is Yellow Freight (YL). • If Yellow Freight cannot make the move, the next favourable carriers are Roadway Express ERD), Con-Way (CW) and Arkansas Best Freight (AB). Carrier Scheduling • Another carrier scheduling activity is the use of intermediaries. • Intermediaries are non-carriers that are used by shippers to locate carriers to physically move the shipper’s products. • The classic intermediaries are the motor carrier freight broker and the railroad intermodal marketing company (IMC). Carrier Scheduling • Shippers experiencing wide swings in demand for transportation find it difficult to establish longterm arrangements with carriers because there are periods throughout the year where there may be no demand for the carrier’s service. • The intermediary maintains contact with hundreds of carriers who have varying amounts of excess capacity and will bring together the shipper and a carrier that is available to haul the loads. • The final carrier scheduling activity is securing the type of equipment needed for the move. • The type of equipment needed depends on the product’s weight, length, width, height, temperature-control requirements, and customer service requirements. • Heavy products requiring overhead cranes to load and unload, products such as the cement highway barriers, may dictate the use of flatbed or open top trailers or rail cars. • For low-density products, shippers request high cube equipment to maximize the amount of product the vehicle can transport. • Finally, the customer may request a particular type of equipment because of physical or operational needs and the seller must comply. • END Load Tendering • Load tendering is the transportation management process that involves the offer and acceptance of the load, loading of the vehicle, and the attendant documentation. • Figure 13.8 presents the different steps included in the load-tendering process. Load Tendering • The carrier accepting the offer will provide a formal acceptance via the transmission methods noted above. • Declining a load offer is no positive response; that is, if the carrier does not accept the load within a preset time limit the assumption is the carrier declines the load. Load Tendering • Once the carrier accepts the load, the shipper arranges a pickup appointment • Today, consignees are requiring the carrier to make a delivery appointment. Load Tendering • The next step in the process is picking, packing, and staging the order. • The order is picked from existing inventory or the items are produced for the order. In the Dell model, a product is produced after the customer places the order. When the order is picked, it is packed for shipment. Load Tendering • In most operations, the items in an order are placed in a box or on a pallet along with packaging material to protect the shipment while in transit. • The final step is to stage the load near the loading dock for quick loading when the truck arrives. • After the vehicle is loaded and the documentation is prepared, the vehicle moves to the consignee’s location for delivery. Documentation • The most common domestic shipping document is the bill of lading. • The bill of lading is the beginning of a transportation shipment • It is the document that provides the carrier with the information necessary for the carrier to complete the move, and it governs the move. Documentation The bill of lading serves the following purposes: • Receipt for the goods tendered to the carrier • Provides shipment information • Contract of carriage • In the case of an order, bill of lading acts as certificate of title to the goods. Documentation • When the carrier’s agent (driver) signs the bill of lading, the carrier has agreed that it has received the items itemized on the document. • The signed bill of lading is the shipper’s receipt that the carrier has taken possession of the goods named on it. • If damage occurs to the shipment, the bill of lading provides proof of what was given to the carrier and the condition of the goods (assumed to be in good condition unless specified otherwise). • STRAIGHT BILL OF LADING vs ORDER BILL OF LADING • The straight bill of lading is a nonnegotiable instrument, which means title cannot be transferred by endorsement. • The order bill of lading is a negotiable instrument and acts as a certificate of title to the goods named on it. Shipment Monitoring • As noted in Figure 13.1 the shipmentmonitoring function involves tracing/expediting, customer communication, and vendor communication. • In essence, shipment monitoring is watching the progress of the shipment through the transportation system and communicating the status or problems to the customer or vendor. Shipment Monitoring • The widespread adoption of the Internet and GPS (Global Positioning System) has greatly enhanced the performance capabilities of carriers with regard to shipment monitoring. Shipment Monitoring • Tracing involves determining where the shipment is at a given moment in time. • With GPS, a carrier can determine within a few yards the exact location of a vehicle and the corresponding shipment. Shipment Monitoring • Once the shipment is traced and its location is noted, the expediting function attempts to hurry the shipment along to delivery. Shipment Monitoring • Customer and vendor communications are the next logical step in the shipment- monitoring process. • If the shipment is going to be delayed, it is incumbent on the shipper to inform the consignee of the delay so the consignee can take appropriate actions. Post-delivery Maintenance • The post-delivery maintenance functions begin once the shipment is delivered, and are designed to make certain the shipment was delivered, cargo damage or loss is recovered, the correct freight charge is paid, and the carrier’s performance is within acceptable limits. • The specific functions include proof of delivery, claims, freight bill auditing, and performance measurement. PROOF OF DELIVERY • The proof of delivery is verification provided by the carrier that the shipment was delivered. CLAIMS • When a shipment is delivered with items damaged or missing, the shipper or consignee files a claim with the carrier to recover the loss. • Figure 13.10 provides an overview of the freight claims process. CLAIMS • The FOB term of sale determines who is legally obligated to file the claim that is determined by the terms of sale. • As noted above, the terms of sale indicates where the title passes to the buyer. • Prior to the point where the title passes to the buyer, the seller is the owner and is required to file the claim. CLAIMS • For example, under an FOB-Origin term of sale, the title passes to the buyer at the shipment origin and the buyer would have responsibility to file the claim. • The seller is responsible for claim filing with the FOB-Delivered term of sale. • CLAIMS • There are many different levels of liability coverage possible for a motor carrier. • The range is from full-value liability with the bill of lading terms to zero liability with a shipper—carrier transportation contract. CLAIMS • The freight claim is a written request the shipper files with the carrier requesting reimbursement for monetary losses resulting from loss, damage, or delay to the shipment or for payment overcharge. CLAIMS • Damage may be either visible or concealed. Visible damage is discovered by the consignee usually at delivery and before opening the package. • Concealed damage is detected after the package is opened. • Concealed damage poses a unique problem in determining when the damage occurred—in the carrier’s or consignee’s possession. CLAIMS • Once the claim is filed, the carrier can agree to pay the claim or deny the claim as indicated in Figure 13.10. • If the carrier agrees to pay, the carrier will forward the appropriate amount to the claimant. • It is not uncommon to find a carrier accepting liability for the damage but negotiating a payment value that is lower than the amount requested in the claim. CLAIMS • If the carrier denies the claim, the claimant must examine the rationale for the denial. • All contested claims are ultimately resolved in court. • To gain legal resolution to the denied claim, the claimant must file a lawsuit within a specified period of time from the date the claim is denied by the carrier. • This is a costly endeavour, and the value of the claim must warrant the legal fees and time involved. FREIGHT BILL AUDITING • Freight bill auditing is used to assess the correct amount to be paid to the carrier. • This is typically done after payment; that is, the audit is performed after the original freight bill is paid. FREIGHT BILL AUDITING The post payment audit process focuses on verification of the freight bill paid by confirming the following: • The shipment was actually made. • The freight bill was not paid previously. • The shipment weight, freight rate, and calculation was noted. • The ancillary services were requested and provided. • The lowest tariff or contract rate was used. FREIGHT BILL AUDITING • The prepayment audit process audits the carrier’s freight bill before payment. • This involves comparing the calculated freight charge with the freight bill submitted by the carrier, and resolving any discrepancies before payment. PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT • The final post-delivery maintenance function is measuring the carrier’s performance. • As shown in Table 13.1, carrier performance measurement considers both cost and service. PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT • The most widely used cost measurements are freight cost as a percentage of sales, cost per unit sold, cost per weight unit, and cost per order. • These cost measurements match the base units used by top management, sales, and purchasing for control. PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT • The service performance measurements are based on the carrier selection criteria discussed in the previous chapter. • On-time pickup and delivery and average transit time are the three most widely utilized service performance measures. GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION PROCESS • Managing the international transportation process is more complex than that of domestic transportation because of the many differences between the trading nations’ transportation and customs regulations, infrastructure, exchange rates, culture, and language. GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION PROCESS • Figure 13.12 depicts the international transportation process. • It begins with the buyer— seller agreement and the management areas of order preparation, transportation, and documentation. Buyer—Seller Agreement • The agreement between the buyer and seller determines the specific transportation criteria the seller must meet. • These criteria include the product to be shipped, financial terms, delivery requirements (date and location), packing, the transportation method(s) to be used, and cargo insurance. • INCOTERMS agreed upon outline/explain the transportation responsibility between the buyer and seller. INCOTERMS • The international terms of sale are known as INCOTERMS. • Unlike domestic terms of sale, in which the buyers and sellers primarily use FOB-origin and FOB-destination terms, there are 13 different INCOTERMS. • Developed by the International Chamber of Commerce, these INCOTERMS are internationally accepted rules defining trade terms. INCOTERMS • The INCOTERMS define responsibilities of both the buyer and seller in any international contract of sale. • For exporting, the terms delineate buyer or seller responsibility for the following: Export packing cost Inland transportation (to the port of export) Export clearance INCOTERMS Vessel or plane loading Main transportation cost Cargo insurance Customs duties Risk of loss or damage in transit E TERMS • The E terms consist of one INCOTERM, Ex Works (EXW). • This is a departure contract that gives the buyer total responsibility for the shipment. • The seller’s responsibility is to make the shipment available at its facility. • The buyer agrees to take possession of the shipment at the point of origin and to bear all of the cost and risk of transporting the goods to the destination (see Figure 13.13 for additional responsibilities of the E Terms). F TERMS • The three F terms obligate the seller to incur the cost of delivering the shipment cleared for export to the carrier designated by the buyer. • The buyer selects and incurs the cost of main transportation, insurance, and customs clearance. • Free Carrier (FCA) can be used with any mode of transportation. • Risk of damage is transferred to the buyer when the seller delivers the goods to the carrier named by the buyer. F TERMS • Free Alongside Ship (FAS) is used for water transportation shipments only. • The risk of damage is transferred to the buyer when the goods are delivered alongside the ship. • The buyer must pay the cost of “lifting” the cargo or container on board the vessel. • Free On Board (FOB) is used for only water transportation shipments. F TERMS • The risk of damage is transferred to the buyer when the shipment crosses the ship’s rail (when the goods are actually loaded on the vessel). • The seller pays the lifting charge (see Figure 13.13 for additional responsibilities on the F Terms). C TERMS • The four C terms are shipment contracts that obligate the seller to obtain and pay for the main carriage and/or cargo insurance. • Cost and Freight (CFR) and Carriage Paid To (CPT) are similar in that both obligate the seller to select and pay for the main carriage (ocean or air to the foreign country). C TERMS • CFR is only used for shipments by water transportation, whereas CPT is used for any mode. • In both terms, the seller incurs all costs to the port of destination. • Risk of damage passes to the buyer when the goods pass the ship’s rail, CFR, or when delivered to the main carrier, CPT. C TERMS • Cost, Insurance, Freight (CIF) and Carriage and Insurance Paid To (CIP) require the seller to pay for both main carriage and cargo insurance. • The risk of damage is the same as that for CFR and CPT (see Figure 13.13 for additional responsibilities of the C Terms). D TERMS • The D terms obligate the seller to incur all costs related to delivery of the shipment to the foreign destination. • There are five D terms; two apply to water transportation only and three to any mode used. • All five D terms require the seller to incur all costs and the risk of damage up to the destination port. D TERMS • Delivered At Frontier (DAF) means the seller is responsible for transportation and incurs the risk of damage to the named point at the place of delivery at the frontier of the destination country. D TERMS • Delivered Ex Ship (DES) and Delivered Ex Quay (or wharf) (DEQ) are used with shipments by water transportation. • Both terms require the seller to pay for the main carriage. • Under DES, risk of damage is transferred when the goods are made available to the buyer on board the ship uncleared for import at the port of destination. • The buyer is responsible for customs clearance. D TERMS • Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) and Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) are available for all modes. Order Preparation • Order preparation involves either picking items ordered from inventory or manufacturing them. • In either case, the seller must make sure the item prepared for shipping matches exactly what is ordered. • Failure to comply with the product specifications contained in the buyer’s purchase order indicates the buyer’s refusal to accept the shipment or to pay the invoice. Order Preparation • Packing for international water shipments is usually more stringent than for domestic shipments because of the increased potential for damage. • Shippers typically use an export packing company to pack the shipment for the rigors of frequent handling, lifting, and storage, as well as the rough ride of international water carriage. Documentation • Global shipment movement is controlled by paper; without proper documentation the shipment does not move. • A missing or incorrect document can delay a shipment and/or prevent the shipment from entering a country. • These documents are governed by the customs regulations of the shipping and receiving nations. • EXPORT LICENSE • SALES DOCUMENTS • Three sales documents are generally used in international trade: a pro-forma invoice, a commercial invoice, and a consular invoice. All three contain essentially the same information: buyer, seller, product descriptions, payment terms, selling price, and other information requested by the buyer, bank, or importing country. • The pro-forma invoice is issued by the seller to acquaint the importer and import government authorities with details of the shipment. • It may be required to obtain necessary foreign exchange information and/or an import license or permit. • The commercial invoice, issued by the seller, is a bill of sale for the goods sold to the buyer, a basis for determining shipment value and importing duty assessment, and a requirement for clearing goods through customs. • The consular invoice is the same as the commercial invoice, except it is a special form prescribed by the importing country and it must be completed in the language of the importing country. FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS • In the buyer—seller agreement, the credit extended by the seller to the buyer is explained and takes the form of either a letter of credit or draft. • The letter of credit, issued by the buyer’s bank, is a guarantee by the buyer’s bank to the seller that payment will be made if certain terms and conditions are met. FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS • These conditions include, for example, documentation, shipping date, time limits, and so on. • If these conditions are not met, payment will be withheld. FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS • The draft is credit extended by the seller directly to the buyer. • It is a written order for a sum of money to be paid by the buyer on a certain date. • Upon presentation of the draft to the buyer’s bank, the buyer’s bank collects the money from the buyer, releases the shipment documentation to permit the buyer to receive the shipment, and remits the money to the seller. CUSTOMS DOCUMENTS • As noted earlier, each nation has a unique set of customs regulations governing the global trade. • In the United States, two common customs documents are the shipper’s export declaration and the certificate of origin. CUSTOMS DOCUMENTS • The shipper’s export declaration is issued by the seller and acts to control the export of restricted goods (implements of war, highlevel technology, etc.) and to provide statistics regarding exporting activity. CUSTOMS DOCUMENTS • The certificate of origin is used to certify the country of origin of the commodities and is particularly important for trade between countries that have special import duty treaties. • For example, NAFTA provides lower import duties for commodities originating in the United States, Canada, or Mexico and destined for one of the respective countries. TRANSPORTATON DOCUMENTS • As with domestic shipments, international shipments require a bill of lading. • The bill of lading acts as a contract of carriage and a receipt for the goods, and provides carrier delivery instructions. • For water shipments, an ocean bill of lading is used; an airway bill is used for air carrier shipments. TRANSPORTATON DOCUMENTS • In addition to the bill of lading, most international shipments require a packing list that provides detailed information of the package contents, dimension, and weight. • A dock receipt is issued by a water carrier when the goods arrive at the dock, but are not loaded onto the ship immediately; this transfers accountability, or liability, from the domestic carrier to the international carrier. Transportation • The transportation elements include the selection of carriers, ports/gateways, intermediaries, and the acquisition of insurance. • At least three carriers are involved in an international shipment: a domestic, an international, and a foreign carrier. Transportation • The international transportation manager must select a domestic carrier to move the goods from the seller’s door to the port or gateway, an international carrier to move it between countries, and a foreign carrier to move it to its final destination in the importing country.