Objective Palliative Prognostic Score among Advanced Cancer

advertisement

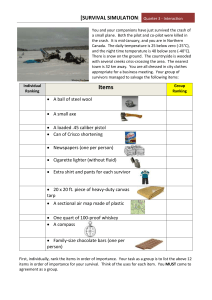

Objective Palliative Prognostic Score among Advanced Cancer Patients Yen-Ting Chen1,3, Chih-Te Ho1,3,4, Hua-Shai Hsu1,3,4, Po-Tsung Huang1,3, Chin-Yu Lin2, Chiu-Shong Liu1,4,5, Tsai-Chung Li6,7, Cheng-Chieh Lin1,4,5,7,Wen-Yuan Lin1,3,4,5 1 Department of Family Medicine, 2Department of Nursing, and 3Hospice Palliative Medicine Unit, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan 4 School of Medicine, 5Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Science and 6Graduate Institute of Biostatistics, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 7 Institute of Health Care Administration, College of Health Science, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan; Co-Author e-mail addresses: Y.T. Chen: jamesytchen@gmail.com C.T. Ho: ctho@mail.cmuh.org.tw H.S. Hsu: lavendertea@pchome.com.tw P.T. Huang: d16973@mail.cmuh.org.tw C.Y. Lin: n4795@mail.cmuh.org.tw C.S. Liu: liucs@ms14.hinet.net T.C. Li: tcli@mail.cmu.edu.tw C.C. Lin: cclin@mail.cmuh.org.tw Correspondence and reprint request to: Wen-Yuan Lin M.D., M.S., Ph.D. Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, 2, Yuh-Der Road, Taichung, Taiwan 404 1 Tel: +886-4-22052121 ext 4507, Fax: +886-4-22361803, E-mail: wylin@mail.cmu.edu.tw Number of tables : 3 Number of figures : 2 Number of references : 32 Word count : 2636 (references no included) 2 Abstract Context. The accurate prediction of survival is one of the key factors in the decision-making process for patients with advanced illnesses. Objectives. This study aims to develop a short-term prognostic prediction method involving such objective factors, past medical history, vital signs, and blood tests, for use with advanced cancer patients. Methods. Medical records gathered upon admission of advanced cancer patients in the Palliative Care Unit at a tertiary hospital in Taiwan were retrospectively reviewed. The records included demographics, history of cancer treatments, performance status, vital signs and biological parameters, Multivariate Cox regression analyses and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve employed for model development. Results. The Objective Palliative Prognostic Score (OPPS) was determined by using six objective predictors identified by multivariate Cox regression analysis. The predictors include heart rate > 120/min, WBCs > 11000/mm3, platelets < 130000/mm3, serum creatinine level > 1.3 mg/dl, serum potassium level > 5 mg/dl, and no history of chemotherapy. The area under the ROC curve used to predict 7 days survival was 82.0% (95% CI: 75.2 to 88.8%). If any three predictors out of the six were reached, survival within 7 days was predicted with 68.8% sensitivity, 86.0% specificity, 55.9% positive predictive value (PPV), and 91.4% negative predictive value (NPV). Conclusions. The OPPS consisted of six objective predictors for the estimation of 7 days survival among advanced cancer patients and showed a relatively high accuracy, specificity, and NPV. Objective signs, such as vital signs and blood tests, may help 3 clinicians make decisions at the very late stages of the life of the patients. 4 Keywords advanced cancer, palliative care, prognosis, survival, prediction 5 Running Title objective palliative prognostic score 6 Introduction Decision making is an important issue in palliative care, especially as patients approach the end of their lives. For patients, families, and physicians, timing the shift from life-prolonging approaches to more palliative ones that focus on quality of life and comfort, is challenging. The accurate prediction of survival is one of the key factors in the decision-making process from goal setting in the early stages of palliative care, which include care giving or expectations of care, to ethical issues at the end of a patient’s life; such ethical issues include withholding and withdrawing treatment, palliative sedation, and nutrition support.1 However, traditional prediction by physicians is unreliable, and most physician prognoses tend to be both imprecise and overly optimistic.2, 3 Many previous studies have formulated survival predictions according to a variety of items, including performance status, symptoms, and biological parameters.4-9 These predictions could significantly help physicians in decision making and in providing patients and their families with useful information for goal setting.6, 10, 11 However, most of these predictions include subjective factors, such as patient symptoms and performance status,12-16 which may be influenced by treatment, time, and physicians. These subjective factors may also be differently evaluated by each caregiver and may be estimated with difficulty by junior physicians. Thus, the idea of being able to create a prognosis from objective factors, such as vital signs and blood test, is appealing to clinicians. A previous study conducted in Italy revealed that white blood cell (WBC), lymphocyte percentage, and pseudocholinesterase levels were independent objective predictors of 7 survival.17 Other studies have also been conducted recently. These studies found that some objective factors, such as leukocytosis, lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), decreased albumin level, high lactate dehydrogenase level, high blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, and high respiratory rate, have prognostic significance in shorter survival.18-23 Decision making in the very late stages of life has more ethical concerns and is more patient-centered, which makes it more difficult for physicians. The diagnosis of death is central to optimal decision making at the end of patient life. However, diagnosing death is often a complex process that has many obstacles, which lend difficulty to the clear recognition of the dying phase.24 Thus, increasing interest has been directed toward the prediction of short-term survival.14, 19, 21, 25, 26 Chiang et al. constructed a 7 days survival prediction model based on cognitive status, edema, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, BUN and respiratory rate with a good area under the curve (AUC) of 0.81 (P<0.001, 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.86).19 Ohde et al. also suggested a two-week prognostic prediction model for terminal cancer patients made up of 5 items: anorexia, dyspnea, edema, BUN > 25.0 mg/dl, and platelet < 260,000/mm3, with a good AUC of 0.83 (0.75-0.91).21 However, both studies still have subjective objects that may potentially be judged by physicians inaccurately. This study primarily aims to develop a validated short-term prognostic prediction consisting objective factors to facilitate the decision making of advanced cancer patients, their relatives, and physicians in the very late stages of life. 8 Methods In this cross-sectional study, cases advanced cancer patients admitted to the Hospice Palliative Care Unit in a tertiary hospital in Taiwan from June 2005 to September 2007 were retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion criteria included patients aged 20 years and above who were admitted to the Hospice Palliative Care Unit of the China Medical University Hospital, have a complete medical record for vital signs, and routinely had basic blood test upon admission. For the patients who were admitted more than twice, the first admission was selected for use in the study. A total of 240 patients were enrolled in this study, and six were excluded because of the lack of survival data. Finally, 234 advanced cancer patients were selected. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the China Medical University Hospital. All potential objective prognostic predictors, including demographic data, diagnostic and therapeutic information, health performance status, vital signs, and biological parameters, were collected by experienced hospice physicians and registered nurses within 24 hours of hospice admission. The potential parameters were based on previous studies or on the clinical experience of physicians. Demographic data include gender, age, and body mass index (BMI). Diagnostic and therapeutic information include the primary site of malignancy and metastasis and history of radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Health performance status was evaluated and recorded through the ECOG performance status. Vital signs recorded at admission include blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen usage. Laboratory tests were conducted through routine blood drawing upon admission. The evaluated parameters include WBC, 9 hemoglobin (Hb), platelets, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), BUN, creatinine (Cr), total bilirubin, albumin, CRP, potassium (K), sodium (Na) and calcium (Ca). Survival days were defined as the period from the date of admission to the Hospice Palliative Care Unit to the date of death. Patients who survived for more than 7 days were labeled as “long survivors,” and those who died within 7 days were labeled as “short survivors.” Statistical analysis Descriptive statistics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). Vital signs and biological parameters were divided into groups based on average, the normal range of our laboratory, the clinical experience of the physicians, and previous studies. 18, 19, 21-23, 27 Student’s t test and Chi-square test were used to reveal differences between long survivors and short survivors. All the candidates for objective predictors with p-value < 0.1 in univariate analyses were selected for the multivariate Cox regression analyses. The independent predictors with p-value < 0.05 in the multivariate analysis comprised final prognostic model, and each score was based on the odds ratio of every predictor. The AUC and survival rate at each point were obtained from the ROC curve. All statistical tests were two sided, with the significance level at 0.05. These statistical analyses were performed using the MAC version of the SPSS statistical software (20th version, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) 10 Results Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics between the long survival and short survival groups. Of the 234 patients, 48 (20.5%) subjects were categorized as short survivors (survival within 7 days), whereas 186 (79.5%) subjects were long survivors. Both groups had slightly more males than females, and the majority of the primary site of malignancy is gastrointestinal. No significant differences were observed in terms of age, BMI, or ECOG between groups. The variables that were more discriminant for shorter survival in the univariate analysis (P<0.05) were brain metastasis and no history of chemotherapy. Table 2 presents the results of the univariate analysis of vital signs and biological parameters. Heart rate > 120 bpm, use of oxygen, WBC > 11000/mm3, platelets < 130000/mm3, ALT > 40 mg/dl, BUN > 26 mg/dl, Cr > 1.3 mg/dl, bilirubin > 2 md/dl, CRP > 8 mg/dl and K > 5.0 mg/dl are related to short-survival. Hb, albumin, Na, and Ca were not associated with the length of survival. Table 3 demonstrates the results of backward stepwise Cox regression analyses. The determinants of patients who died within 7 days (short survival) are no history of chemotherapy, HR >120 bpm, WBC > 11000/mm3, platelet < 130000/mm3, Cr > 1.3mg/dl, and K > 5 mg/dl. The determinants were subsequently selected as prognostic predictors based on a p-value <0.05. The final models of prognostic prediction were employed to establish the Objective Palliative Prognostic Score (OPPS) and ROC curves (Figure 1). The AUC was 82.0% (95% CI: 75.2 to 88.8%). When total scores are 0 to 2 points, 3 points, or 4 to 5 points, one-week mortality rates are 8.6%, 50% and 73.3%, respectively (Figure 2). If any three 11 predictors out of the six were reached, survival within 7 days was predicted a sensitivity of 68.8%, specificity of 86.0%, positive predictive value of 55.9% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 91.4%. 12 Discussion In this study, we proposed a prognostic prediction model, the OPPS, for estimating the probability of 7 days survival among advanced cancer patients. To our knowledge, OPPS is the first prognostic survival prediction model exclusively composed of objective factors. The six predictors identified by the multivariate Cox regression analyses are (1) no history of chemotherapy, (2) heart rate > 120 bpm, (3) WBC > 11000/mm3, (4) platelets < 130000/mm3, (5) Cr > 1.3 mg/dl, and (5) K > 5.0 mg/dl. In our study, the AUC showed relatively good accuracy (AUC: 0.82, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.89). The OPPS also showed high specificity (86%) and high NPV (91.4%) for predicting 7 days survival when 3 predictors were reached. Hemodynamic statuses are routinely recorded routinely as important clinical signs, and hemodynamic changes, such as drop of blood pressure, tachycardia or bradycardia, are frequently noted during the dying process. Tachycardia was a significantly independent predictor noted in this study and was also reported by Elsayem and Mercadante et al. for short-term survival among terminal cancer patients.20, 23 Lower blood pressure was not a significant factor in our analysis, though Mercadante et al. reported lower systolic blood pressure as a significant factor for shorter survival in advanced cancer patients who received home care service.23 By contrast, Elsayem et al. reported that diastolic blood pressure was not a significant factor, similar to our model, which warrants further investigation.20 Leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and elevated serum Cr and K levels, as biological parameters, are independent prognostic factors in this multivariate analysis and are included 13 in the formula for OPPS. Leukocytosis is a well-known survival predictor in advanced cancer patients.4, 6, 10 In our analysis, leukocytosis also worked well in short-term survival prediction. Thrombocytopenia is common in terminal patients because of the impaired production of platelets caused by the decrease or absence of megakaryocytes owing to the myelosuppressive effects of chemotherapy or radiation therapy or as a result of the infiltration of the bone marrow by malignant cells.28 Ohde et al. also suggested that the members of the low platelet group of terminal cancer patients are more likely to die within two weeks.21 Impaired renal function is another common condition among terminal cancer patients. Both Chiang and Ohde et al. included elevated serum BUN level in their models as a predictor for short-term survival.19 In our multivariate analyses, elevation in BUN and Cr are both independent predictors for patients that died within 7 days. Including elevated Cr level in the formula results in better AUC than including elevated BUN level. This study is unique because of the inclusion of hyperkalemia in the OPPS. Electrolyte imbalance, a very common condition in advanced cancer patients, has never been included in previous prognostic models. Hyperkalemia was found to be an accurate predictor for 7 days survival. One notable finding in our study is that no history of chemotherapy is also included in our prognostic model. Patients who have received chemotherapy might have better survival.29-31 However, no study has proven that chemotherapy could be used in the prediction of short-term survival. This topic warrants further investigation. The accuracy prediction of survival is very important in palliative care sot that appropriate treatment can be arranged and discussion with the patients and their families about goal 14 setting can be facilitated. Clinical prognoses are mostly based on physician experience and the observation of the clinical condition of the patient. However, the causes of death in advanced cancer patients vary, and not every patient has a smooth downward trajectory. Although terminal symptoms, such as dyspnea, anorexia, and poor performance, are very strong predictors for the dying process,7, 9, 32 terminal patients who are near death may exhibit minimal clinical change in very late stages of life. Clinicians often find great difficulty in making treatment decisions in the very late stages of life of the patients, especially in performing invasive procedures or withdrawing life-sustaining therapy. A useful prognostic tool for the prediction of short-term survival may help guide treatment. Chiang et al. established a prognostic 7 days survival formula for patients with terminal cancer patients. This formula consisted three subjective clinical findings and two objective records (BUN and respiratory rate). The formula also had good accuracy in AUC (0.81, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.86) and high NPV (91.7%), which are similar to the findings of this study. However, the predictor model established based on a complicated formula can not be easily applied to the clinical setting. This study has some limitation. The final prognostic prediction model retrospectively derived from a single institution with a limited numbers of patients may have a limited nature and may be over-fitted, and the degree and criteria of patients admitted to palliative care differ around the world. Patients are admitted to our Hospice Palliative Care Unit mostly because of acute problems, such as pain, infection, electrolyte imbalance, or conscious disturbance. Thus, blood sampling upon admission is usually performed. However, blood sampling, being an 15 invasive procedure that is uncomfortable for patients, may not be routinely performed in some palliative care facilities. Moreover, this prognostic score is solely applied to advanced cancer patients and may not be applicable to non-cancer patients. These findings require further evaluation in larger prospective studies. In conclusion, we suggest a 7 days prognostic prediction score for advanced cancer patients. This score consists of six objective factors, namely, heart rate > 120 bpm, WBCs > 11000/mm3, platelets < 130000/mm3, Cr > 1.3 mg/dl, K > 5 mg/dl, and no history of chemotherapy. The OPPS has a good AUC (82.0%, 95% CI: 75.2 to 88.8%). When three predictors were reached, death within 7 days was predicted with relatively good specificity (86.0%) and NPV (91.4%). OPPS is the first prediction model for survival of the advanced cancer patients that is made up of only objective subjects. The findings of this study may provide useful information for the development of new prognostic models. 16 Disclosures and Acknowledgements This study was financially supported by grants from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC94-2314-B-039-025, NSC95-2314-B-039-008, and NSC96-2314-B-039-015) and China Medical University Hospital (DMR-99-109, and DMR-101-058, and DMR-102-065). We thank the medical staff and all participants in hospice palliative medicine for their assistance in completing this study. 17 References 1. Weissman DE. Decision making at a time of crisis near the end of life. JAMA 2004;292:1738-43. 2. Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327:195-8. 3. Gripp S, Moeller S, Bölke E, et al. Survival prediction in terminally ill cancer patients by clinical estimates, laboratory tests, and self-rated anxiety and depression. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007;25:3313-20. 4. Viganó a, Bruera E, Jhangri GS, et al. Clinical survival predictors in patients with advanced cancer. Archives of internal medicine 2000;160:861-8. 5. Viganò a, Dorgan M, Buckingham J, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor ME. Survival prediction in terminal cancer patients: a systematic review of the medical literature. Palliative medicine 2000;14:363-74. 6. Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2005;23:6240-8. 7. Stone PC, Lund S. Predicting prognosis in patients with advanced cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO 2007;18:971-6. 18 8. Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease. European journal of cancer 2008;44:1146-56. 9. Ripamonti CI, Farina G, Garassino MC. Predictive models in palliative care. Cancer 2009;115:3128-34. 10. Maltoni M, Nanni O, Pirovano M, et al. Successful validation of the palliative prognostic score in terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. Journal of pain and symptom management 1999;17:240-7. 11. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. Improved accuracy of physicians' survival prediction for terminally ill cancer patients using the Palliative Prognostic Index. Palliative Medicine 2001;15:419-24. 12. Pirovano M, Maltoni M, Nanni O, et al. A new palliative prognostic score: a first step for the staging of terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter and Study Group on Palliative Care. Journal of pain and symptom management 1999;17:231-9. 13. Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. Journal of Palliative Care 1996;12:5-11. 14. Caraceni A, Nanni O, Maltoni M, et al. Impact of delirium on the short term prognosis of advanced cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. Cancer 2000;89:1145-9. 15. Chuang R-B, Hu W-Y, Chiu T-Y, Chen C-Y. Prediction of survival in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan: constructing a prognostic scale. Journal of pain and symptom management 2004;28:115-22. 19 16. Yun YH, Heo DS, Heo BY, et al. Development of terminal cancer prognostic score as an index in terminally ill cancer patients. Oncology Reports 2001;8:795-800. 17. Maltoni M, Pirovano M, Nanni O, et al. Biological indices predictive of survival in 519 Italian terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 1997;13:1-9. 18. Kikuchi N, Ohmori K, Kuriyama S, et al. Survival prediction of patients with advanced cancer: the predictive accuracy of the model based on biological markers. Journal of pain and symptom management 2007;34:600-6. 19. Chiang J-K, Lai N-S, Wang M-H, Chen S-C, Kao Y-H. A proposed prognostic 7-day survival formula for patients with terminal cancer. BMC public health 2009;9:365. 20. Elsayem A, Mori M, Parsons Ha, et al. Predictors of inpatient mortality in an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2010;18:67-76. 21. Ohde S, Hayashi A, Takahasi O, et al. A 2-week prognostic prediction model for terminal cancer patients in a palliative care unit at a Japanese general hospital. Palliative medicine 2011;25:170-6. 22. Partridge M, Fallon M, Bray C, et al. Prognostication in advanced cancer: a study examining an inflammation-based score. Journal of pain and symptom management 2012;44:161-7. 23. Mercadante S, Valle A, Porzio G, et al. Prognostic factors of survival in patients with advanced cancer admitted to home care. Journal of pain and symptom management 20 2013;45:56-62. 24. Solomon MZ, O'Donnell L, Jennings B, et al. Decisions near the end of life: professional views on life-sustaining treatments. American journal of public health 1993;83:14-23. 25. Bozcuk H, Koyuncu E, Yildiz M, et al. A simple and accurate prediction model to estimate the intrahospital mortality risk of hospitalised cancer patients. International journal of clinical practice 2004;58:1014-9. 26. Stone P, Kelly L, Head R, White S. Development and validation of a prognostic scale for use in patients with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine 2008;22:711-7. 27. Suh SY, Ahn HY. Lactate dehydrogenase as a prognostic factor for survival time of terminally ill cancer patients: a preliminary study. European Journal of Cancer 2007;43:1051-9. 28. Avvisati G, Tirindelli MC, Annibali O. Thrombocytopenia and hemorrhagic risk in cancer patients. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2003;48:S13-S16. 29. Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, et al. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. The lancet oncology 2007;8:226-34. 30. Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. The New England journal of medicine 2012;367:1187-97. 31. Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated 21 meta-analysis. The lancet oncology 2011;12:681-92. 32. Innes S, Payne S. Advanced cancer patients' prognostic information preferences: a review. Palliative medicine 2009;23:29-39. 22 Table 1: Baseline characteristics between short and long survivors Short-survival Long-survival Patient number (%) 48 (20.5) 186 (79.5) Male, n (%) 31 (64.6) 100 (53.8) 0.195 Age, mean (SD) 62.8 (13.6) 62.9 (14.2) 0.783 BMI, mean (SD) 19.6 (3.4) 19.7 (3.5) 0.909 ECOG, n (%) p-value 0.703 1 2 (4.2) 11 (5.9) 2 13 (27.1) 49 (26.3) 3 13 (27.1) 63 (33.9) 4 20 (41.7) 63 (33.9) Primary site, n (%) 0.660 GI 21 (43.8) 75 (40.3) Lung 5 (10.4) 37 (19.9) GU 2 (4.2) 11 (5.9) Head and neck 8 (16.7) 28 (15.1) Breast 2 (4.2) 8 (4.3) others 10 (20.8) 27 (14.5) Liver 14 (29.2) 58 (31.2) 0.862 Lung 15 (31.2) 59 (31.7) 1.000 Metastasis, n (%) 23 Bone 17 (35.4) 69 (37.1) 0.868 Brain 3 (6.2) 36 (19.4) 0.030 Lymph 7 (14.6) 35 (18.8) 0.673 Abdomen 4 (8.3) 10 (5.4) 0.494 History of chemotherapy, n (%) 21 (43.8) 117 (62.9) 0.021 History of Radiotherapy, n (%) 22 (45.8) 94 (50.5) 0.628 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary. 24 Table 2: Vital signs and biological parameter data between short and long survivors. Short-survival Long-survival p-value SBP < 100 mmHg, n (%) 8 (16.7) 26 (14.0) 0.648 HR > 120 BPM, n (%) 19 (39.6) 33 (17.7) 0.003 Use of oxygen, n (%) 29 (60.4) 79 (42.7) 0.034 Ascites, n (%) 8 (16.7) 22 (11.8) 0.345 WBC > 11000/mm3, n (%) 35 (72.9) 75 (40.3) < 0.001 Hb < 10 g/dl, n (%) 19 (39.6) 81 (43.5) 0.744 Platelet < 130000/mm3, n (%) 17 (35.4) 33 (17.7) 0.011 ALT > 40 U/L, n (%) 10 (20.8) 13 (7.0) 0.011 BUN > 26 mg/dl, n (%) 26 (54.2) 46 (24.7) < 0.001 Cr > 1.3 mg/dl, n (%) 25 (52.1) 37 (19.9) < 0.001 Total bilirubin > 2 mg/dl, n (%) 16 (33.3) 34 (18.3) 0.030 Albumin < 2 g/dl, n (%) 23 (47.9) 74 (39.8) 0.328 CRP > 8 mg/dl, n (%) 30 (62.5) 79 (42.5) 0.015 K > 5 mEq/L, n (%) 12 (25.0) 10 (5.4) < 0.001 Na < 135 or > 150 mEq/L, n (%) 31 (64.6) 139 (74.7) 0.203 Ca > 10 mEq/L, n (%) 16 (8.6) 0.274 7 (14.6) Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; WBC, white blood cell count; Hb, hemoglobin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; K, potassium; Na, sodium; Ca, calcium. 25 Table 3: Results of backward stepwise Cox regression analyses: determinants of patients who died within 7 days odds ratio 95% CI p-value score no chemotherapy 3.137 1.427-6.896 0.004 1 HR > 120 BPM 2.791 1.244-6.264 0.013 1 WBC > 11000/mm3 3.575 1.585-8.067 0.002 1 Platelet < 130000/mm3 3.657 1.564-8.551 0.003 1 Cr > 1.3 mg/dl 3.295 1.495-7.261 0.003 1 K > 5 mg/dl 3.760 1.237-11.426 0.020 1 Abbreviations: HR, heart rate; WBC, white blood cell count; Cr, creatinine; K, potassium 26 Figure 1: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of Objective Palliative Prognostic Score. Abbreviation: AUC, area under the curve. 27 Figure 2: Mortality rate within 7 days based on Objective Palliative Prognostic Score 28