Horizontal Hostility and the Nursing Profession: Why

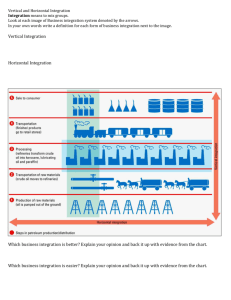

advertisement

Running head: HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING Horizontal Hostility and the Nursing Profession: Why Do Nurses Eat Their Young? Nicki Croel Ferris State University 1 HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 2 Abstract This paper focuses on horizontal hostility in the nursing profession. Nurses are one of the most trusted professionals, and nursing itself is thought of as caring, compassionate, and trustworthy. Why then, are nurses known for “eating their young?” This paper will focus on the incidences of horizontal hostility and the problems that arise from that behavior. Both nursing and interdisciplinary theories that relate to horizontal hostility will be explored. Policies, resources, quality, and safety issues that horizontal hostility impact will be examined, as well as inferences, implications, and consequences. Finally, recommendations with a basis in the American Nurses Association (ANA) professional standards and Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) competencies will be presented. HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 3 Horizontal Hostility and the Nursing Profession: Why Do Nurses Eat Their Young? Horizontal hostility is also known as lateral violence, bullying, verbal abuse, interactive workplace trauma, relational aggression, and covert impersonal conflict (Bartholomew, 2006; Dellasega, 2009). Horizontal hostility is defined as “a consistent pattern of behavior designed to control, diminish, or devalue a peer (or group) that creates a risk to health and/or safety” (Bartholomew, 2006, p. 4). Townsend defined bullying as “repeated, offensive, abusive, intimidating, or insulting behaviors; abuse of power; or unfair sanctions that make recipients feel humiliated, vulnerable, or threatened, thus creating stress and undermining their self-confidence” (2007, p. 12) This paper will use the term horizontal hostility to describe behavior that fits these definitions. There are many different behaviors that can fall into the definition of horizontal hostility, but generally the behavior is either overt or covert. Overt behaviors are readily apparent, and are easily quantified. For example, behaviors like “name-calling, bickering, fault-finding, backstabbing, criticism, intimidation, gossip, shouting, blaming, using put-downs, raising eyebrows, etc.” are all considered overt behaviors (Bartholomew, 2006, p. 5). Covert behaviors can be more subtle, therefore more difficult to determine. Behaviors like “unfair assignments, sarcasm, eye-rolling, ignoring, making faces behind someone’s back, refusing to help, sighing, whining, refusing to work with someone, sabotage, isolation, exclusion, fabrication, etc.” are all considered covert behaviors of horizontal hostility (Bartholomew, 2006, p. 5). This behavior can have several negative consequences for nurses, patients, and healthcare as a whole. HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 4 Impact Nursing Horizontal hostility can have numerous negative health implications on nurses who experience and witness this behavior. Health problems can include insomnia, low self-esteem, poor workplace morale, a feeling of disconnectedness, depression, increased absenteeism, headaches, digestive problems (such as irritable bowel syndrome), irritability, anxiety, depression, loss of concentration, weight changes, alcohol and/or drug abuse, and hypertension (Barton et al., 2011; Longo, 2013; Townsend, 2007; Vogelpohl, Rice, Edwards, & Bork, 2013). Townsend goes on to state, “Bullying affects bystanders as well, making them wonder if they’ll be the bully’s next victim; this stress can lead to depression and anger” (2007, p. 14). Many witnesses are afraid to report unacceptable behavior to avoid being the bully’s next target (Townsend, 2007). Rates of horizontal hostility between nurses are quite eye-opening. In one study “60% of RNs in the United States were found to leave their first position within 6 months because of horizontal violence” (Vogelpohl et al. 2013, p. 415). Vogelpohl et al. go on to report that according to a 2008 Joint Commission survey “50% of nurses had been a victim of bullying and/or disruptive behavior in the workplace, and 90% stated that they witnessed others being the brunt of abuse within their organization” (2013, p. 415). According to Longo, RNs who have worked less than 5 years were most at risk of bullying behavior, but nurses with longevity, therefore greater nursing knowledge, are also leaving units, organizations, or nursing because of bullying (2013). This exodus from nursing impacts patient care. HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 5 Patients Horizontal hostility not only affects nurses, patient safety and care are at risk when a culture of incivility has been allowed to persist. “Health-care workers have associated incidences of inappropriate behaviours, such as bullying, with potential or actual errors, specific adverse outcomes and patient mortality” (Longo, 2013, p. 951). Other adverse outcomes from horizontal hostility include “complications from errors, accidents, or poor work performance” (Barton et al., 2011, p. 356). Both nurse performance and patient outcomes affect healthcare as a whole. Healthcare Organizations Healthcare organizations need to address their workplace culture to determine if horizontal hostility occurs. “Roughly 60% of new RNs quit their first job within 6 months of being bullied” (Townsend, 2007, p. 12). Research from Nursing Solutions, Incorporated indicated that over 80% of nurses who have left an organization indicate peer and nurse manager relationships as the reason for leaving, and “79% cite a more desirable work culture elsewhere” (Bennett &Sawatzky, 2013, p. 144). The cost associated with turnover, hiring, and training is enormous and this cost is a waste of money which could be better spent elsewhere in healthcare. Theoretical Base Nursing Theory Dr. Marion Conti-O’Hare’s Theory of the Nurse as the Wounded Healer, applies the idea that every nurse has experienced trauma in their professional life, personal life, or both. If this trauma is left unresolved, the person’s coping mechanisms are ineffective. Nurses thereby function as ‘walking wounded’ and “experience problems in their social, intimate, and work relationships” (Christie & Jones, 2013, Overview of the Theory of the Nurse as a Wounded HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 6 Healer section, para. 1). Nurses are “projecting their woundedness on both patients and colleagues while considering themselves unharmed, yet being less able to empathize with others” (Christie & Jones, 2013, Overview of the Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer section, para. 1). Resolving the pain associated with trauma, transforms and transcends it into healing. “Although the injury has occurred, the wounds have been sufficiently understood and processed and will not interfere with providing care” and the nurse is better able to provide care (Christie & Jones, 2013, Overview of the Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer section, para. 2). The nurse can better build a therapeutic relationship with others because of understanding the personal pain and suffering they have gone through (Christie & Jones, 2013). Nursing is considered a highly stressful work environment and “nurses are in need of an ‘outlet’ in which to vent their negative emotions and cognitions. Unfortunately vulnerable peers and co-workers frequently end up being this outlet, thus becoming victims of lateral violence” (Christie & Jones, 2013, Theory Application to Lateral Violence in Nursing section, para. 1). Student nurses, newly registered nurse, nurses new to the organization or unit, and night shift nurses are at greater risk to experience horizontal hostility (Christie & Jones, 2013; Sauer, 2012). According to Christie and Jones (2013) horizontal hostility behavior may initially start as passive aggression or minor bullying to the aforementioned risk groups. Apologies may be issued, but the aggression can escalate into either covert or overt forms of horizontal hostility, eventually becoming the norm of the unit. Nurses begin to regularly experience or witness this behavior, all becoming the walking wounded. Each nurse, according to this theory must go through recognition, transform, and finally transcend this pain in order to become the wounded healer (Christie & Jones, 2013). HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 7 According to Christie and Jones, recognition of the event helps the nurse realize what happened, what could be changed, and how should it have been handled (2013). The next step, transformation, helps the nurse change the pain into understanding, by asking what can be learned from this incident, has this changed me or the people I care about, and how can this be used to make things better (Christie & Jones, 2013). When the first two steps are complete, transcending the pain, obtaining insight, and learning can happen. The nurse can say “I understand your pain, and how can I make things better for you” (Christie & Jones, 2013, Theory Application to Lateral Violence in Nursing section, para. 5). Oppression Theory According to Charney, Paulo Freire’s oppression theory can explain how a profession that cares for others, can turn on their own (2012). Oppression theory states a dominant group creates a culture based on their values and beliefs. The members of the dominated group begin to change themselves and reject their beliefs and values. This behavior can lead to a lack of selfesteem and decreases the respect for each other within their own group. The dominated group feels aggression, but they are unlikely to confront the dominant group’s authority and power. The aggression and anger are turned inward to their own group (Charney, 2012). “Nursing as a group has been viewed as oppressed because of its lack of power and control in the workplace” (Charney, 2012, p. 214). Horizontal hostility is the outcome from frustrations stemming from confrontations with other, non-nursing co-workers (Charney, 2012). It is contended that nurses are dominated, therefore oppressed, by a patriarchal system headed by doctors, administrations, and marginalized nurse managers, nurses lower down the hierarch of power resort to aggression among themselves. It is believed that nurses have little control over their work environment and yet are held responsible for a great HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 8 deal, resulting in personal stress. The members of the oppressed group are abusive to peers and those individuals with lesser status because they are unwilling to confront the source of their frustration. (Charney, 2012, p. 215). Assessment of the Healthcare Environment Policies Horizontal hostility has not gone unnoticed by policy makers in the healthcare field. The ANA issued a position statement regarding this type of toxic workplace. In 2006 the House of Delegates passed a resolution stating all nurses have the right to work free of harassment, which includes bullying and horizontal hostility (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2006). The Resolution goes on to state the Code of Ethics applies in all workplaces and supersedes any other institutional or workplace policies (ANA, 2006). Finally, the resolution states nurses should have protection from retaliation when reporting behavior that violates this standard (ANA, 2006). The ANA’s position statement gives guidance to nurses and provides a framework to shape institutional policies. The Joint Commission has also weighed in on horizontal hostility. In 2008, Sentinel Event Alert #40 was issued titled “Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety” (The Joint Commission, 2008). The alert highlights some of the troubling healthcare worker and patient outcomes that can arise when horizontal hostility is not addressed. Sentinel Event Alert #40 states “Intimidating and disruptive behaviors can foster medical errors, contribute to poor patient satisfaction and adverse outcomes, increase the cost of care, and cause qualified clinicians, administrators and managers to seek new positions in more professional environments” (The Joint Commission, 2008, p. 1). The Joint Commission recognizes this behavior is detrimental to collaboration and teamwork. In order to be accredited by The Joint Commission organizations HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 9 must do the following: “The hospitals/organization has a code of conduct that defines acceptable and disruptive and inappropriate behaviors” and “Leaders create and implement a process for managing disruptive and inappropriate behaviors” (The Joint Commission, 2008, p. 2). These processes help to interrupt the cycle of horizontal hostility thereby making hospitals safer. Resources The ANA has several resources for individuals to increase their knowledge of horizontal hostility. There are three continuing education modules available on the ANA’s website. “Navigating the Work Environment: Embracing a Zero Tolerance for Bullying” is the title of the first module and it is described as teaching one how to address behaviors like gossiping and information withholding (ANA, 2014, Take Action Now section, para. 1). Secondly, “Lateral Violence: Nurse Against Nurse” is a module that helps one “Learn to recognize and address lateral violence in the nursing workplace” (ANA, 2014, Take Action Now section, para. 2). Lastly, the module titled “Workplace Violence: The Nurse Victim” is a module that is focused on “the signs, interventions, and prevention of secondary traumatization of care providers” (ANA, 2014, Take Action Now section, para. 3). The ANA also has an e-book available on their website titled, Bullying in the Workplace: Reversing a Culture and is described as enabling “nurses to understand and deal with bullying and its perpetrators and to counter the culture of bullying in their work environment” (ANA, 2014, Tools You Need section, para. 3). Quality and Safety Several quality and safety issues have already been addressed prior in this paper. This behavior can have several adverse outcomes for both nurses and patients. This behavior especially impacts new nurses. Horizontal hostility prohibits them from asking clarifying HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 10 questions, increasing their knowledge, seeking validation of known knowledge, and feeling like they fit in, which all negatively impact their learning (Griffin, 2004). There are also negative patient outcomes that affect quality and safety. Nurses have reported reluctance to clarify orders, used new equipment with which they were unfamiliar, ambulated or lifted dependent patients without asking for help, and carried out orders they did not think was in the patient’s best interest (Wilson & Phelps, 2013). These behaviors all jeopardize the healthcare system’s best intentions to reduce adverse patient outcomes. Inferences, Implications & Consequences Nurses who experience and witness horizontal hostility suffer ill effects (Dellasega, 2009). Some of the literature compares these effects to post traumatic stress disorder, “50% continue to suffer from stress five years after the incident” (Bartholomew, 2006, p. 13). According to Townsend witnesses wonder “if they’ll be the bully’s next victim; this stress can lead to depression and anger” and they are afraid to report abuse out of fear of retaliation (2012, p. 14). Refer to the Nursing Impacts section for previously stated health outcomes for nurses. Another major problem of horizontal hostility is the loss of experienced nurses who move to other units, organizations, or leave nursing altogether. This exacerbates the nursing shortage which is projected to be as great as 260,000 by the year 2025 (Longo, 2013). The vacancies take time to be replaces, trained, and orientated, which leaves units and organizations short staffed. Hiring and training nurses is expensive. One study places the cost of nurse turnover at $64,000 per nurse (Barton et al., 2011). According to Vogelpohl et al. “A hospital with a poor nursing retention rate could spend annually an average of $3.6 million more than a hospital with a good nursing retention rate” (2013, p. 414). Another study estimated the cost of replacing a specialty nurse to be as great as $145,000 (Becher & Visovsky, 2012). Research by Bennett and HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 11 Sawatzky (2013) indicate that for every percentage point increase in nurse turnover, it costs healthcare organizations $600,000. In an era of shrinking margins and reimbursements, time and money spend on reducing nurse turnover could be better spent on patient care Recommendations for Quality and Safety Improvements Upon review of the literature there are several recommendations to counter horizontal hostility. The recommendations include education, training, conflict management techniques, and teambuilding. Initiating these recommendations will help to improve the culture of our nation’s healthcare organizations. The Joint Commission listed several recommendations in Sentinel Event Alert #40. These recommendations include education of all staff members, including physicians. This education should focus on the appropriate behavior, etiquette, phone, and people skills. The code of behavior mandated by The Joint Commission needs to be applied equitably to all professional in healthcare organizations. There should be a zero-tolerance policy regarding horizontal hostility, protection for whistleblowers, and policies for addressing patients or their families who witness or are involved in incidences of horizontal hostility. There must be processes in place for employees to report horizontal hostility, possibly anonymously. Managers should be educated in ways to provide feedback to their employees regarding unprofessional behaviors. Collaboration between disciplines should be encouraged (The Joint Commission, 2008). Bartholomew has several recommendations for new nurses in healthcare organizations (2006). These recommendations include addressing behaviors towards student nurses, addressing horizontal hostility in nursing schools, and new resident nurses. Education, HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 12 increasing opportunities for communication, establish relationships and expectations, revising curriculum, and debriefing (Bartholomew, 2006). Organizations should address horizontal hostility during orientation. In a study by Griffin, new nurses at a Boston hospital were given scripted responses addressing some of the most commonly seen horizontal hostility behaviors (2004). After following the new nurses for a year, the researches performed a follow up interview. All of the nurses addressed hostile behavior with another nurse. They all reported the confrontation was difficult, but the unwanted behavior ceased. Providing new nurses tools and education to address this behavior was effective in this study (Griffin, 2004). In another research article an ambulatory surgical center (ASC) reported on their efforts to decrease horizontal hostility and increase workplace morale (Dimarino, 2011). After a new manager took over, the code of conduct at the ASC was revised and a zero-tolerance policy was initiated. New hires were educated about the expectations in adhering to the code of conduct and an open door policy was instituted by management. After making these changes, the ASC reported no staff turnover, staff reports feeling satisfied and recommends their friends for open positions at that ASC, and patient satisfaction has improved (Dimarino, 2011). Conclusion Horizontal hostility is an insidious and toxic problem in our nation’s healthcare organizations. There are several documented incidences of negative outcomes from nurses, patients, and organizations. The increased risk of errors and the cost hostility and nurse turnover imposes on organizations is a big problem. Fortunately managers, administrators, and others in leadership positions are looking at ways to address this issue. There have been numerous instances of organizations addressing behavior and improving behaviors seen between nurses. HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 13 Some of the most effective policies implemented are a combination of education, management commitment to improve behaviors, and equal enforcement between all disciplines working in health care. The Joint Commission and the ANA focus time and attention to provide recommendations and guidance. Those most vulnerable to horizontal hostility should identify their resources and be willing to confront nurses’ if incivility is present. Those who have reported confrontation said it was difficult, but addressing the behavior is one of the most effective ways to change the culture. HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 14 References American Nurses Association. (2014). Bullying and workplace violence. In ANA: American Nurses Association. http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Nurse/bullyingworkplaceviolence American Nurses Association. (2006). Workplace abuse and harassment of nurses. http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/WorkplaceSafety/HealthyNurse/bullyingworkplaceviolence/WorkplaceAbuseandHarassmentofNurses.pdf Bartholomew, K. (2006). Ending nurse-to-nurse hostility: Why nurses eat their young and each other. Marblehead, MA: HCPro. Barton, S. A., Alamri, M. S., Cella, D., Cherry, K. L., Curll, K., Hallman, B. D.,… & Zuraikat, N. (2011, August). Dissolving clique behavior. Nursing Management, 42(8). doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000399677.43428.73 Becher, J., & Visovsky, C. (2012, July). Horizontal violence in nursing [Electronic version]. MEDSURG Nursing, 21(4). Bennett, K., & Sawatzky, J. V. (2013, April). Building emotional intelligence: A strategy for emerging nurse leaders to reduce workplace bullying. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 37(2). doi:10.1097/NAQ.0b013e318286de5f Charney, W. (Ed.). (2012). Epidemic of medical errors and hospital-acquired infections: Systemic and social causes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Christie, W., & Jones, S. (2013, December 9). Lateral violence in nursing and the theory of the nurse as the wounded healer. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(1). doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No01PPT01 HORIZONTAL HOSTILITY AND NURSING 15 Dellasega, C. A. (2009, January). Bullying among nurses [Electronic version]. American Journal of Nursing, 109(18). Dimarino, T. J. (2011, May). Eliminating lateral violence in the ambulatory setting: One center's strategy. Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses, 93(5). doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.10.019 Griffin, M. (2004, November). Teaching cognitive rehearsal as a shield for lateral violence: An intervention for newly licensed nurses [Electronic version]. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 35(6). doi:10.1097/NHL.0b013e3182861503 Longo, J. (2013, August). Bullying and the older nurse. Journal of Nursing Management, 21. doi:10.1111/jonm.12173 Sauer, P. (2012, January). Do nurses eat their young? Truth and consequences [Electronic version]. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 38(1). doi:10.1016/j.jen.2011.08.012 The Joint Commission. (2008, July 9). Sentinel event alert, issue 40: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_40.PDF Townsend, T. (2012, January). Break the bullying cycle [Electronic version]. American Nurse Today, 7(1). Vogelpohl, D. A., Rice, S. K., Edwards, M. E., & Bork, C. E. (2013, November). New graduate nurses' perception of the workplace: Have they experienced bullying? Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(6). doi:http://0dx.doi.org.libcat.ferris.edu/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.10.008 Wilson, B. L., & Phelps, C. (2013, January). Horizontal hostility: A threat to patient safety. JONA'S Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation, 15(1).