Comprehensive Exam Sociology of Education (Transition to

advertisement

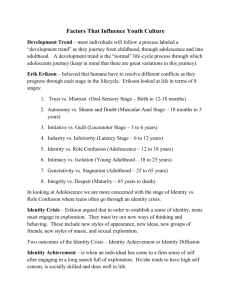

Comprehensive Exam Sociology of Education (Transition to Adulthood Specialty) Spring 2012 A. CHOOSE ONE OF THE FOLLOWING TWO QUESTIONS: 1. Many important trends have occurred in the U.S. post-secondary education system over the last decade. Overall, the share of high school graduates that are continuing on to college has been steadily increasing. However, some evidence suggests that by family type, participation rates have risen across all income levels, but that the increases have been greater for individual from middle- and upper-class families compared to those from low-income families. What role do schools play in determining who goes on to post-secondary education? What changes should be made to the way children are educated in K-12 to ensure that individuals have the opportunity to go to college or university without regard to family background? 2. Given the importance of attending and graduating from college for individuals’ future life chances (including occupational status, income, and health), postsecondary education can provide a crucial opportunity for social mobility, or alternatively, function as a key mechanism in social reproduction. Based on your readings, do you think that postsecondary education has contributed more to the former or to the later? And do you think that the role of postsecondary education in promoting either social mobility or reproduction has changed over time? If so, why? And if not, why not? B. CHOOSE TWO OF THE FOLLOWING THREE QUESTIONS: 1. School transitions are normative experiences that involve a shift in both the structural characteristics of the schools youth attend and the relationships and interactions that occur within and across school contexts. Accordingly, school transitions are instrumental for adolescents’ academic achievement. For instance, studies have demonstrated that transitions to middle and high school are often associated with decreased academic achievement. Discuss two theoretical perspectives that help us understand the link between transitions and academic outcomes. In this discussion, detail the aspects of individuals, families, and school contexts that are thought to contribute to such academic declines? Also, what are some strengths and weaknesses of these theories? 2. Education serves key functions in modern society, with important consequences for both individuals and society as a whole. Concentrating on the consequences for individuals, consider effects of education on labor force, family and health. Use evidence to suggest important avenues for future research 3. In a remarkably short period of time, girls and women have gone from enrolling at lower levels in higher education to dominating among college ready applicants and college graduates. Should we worry about the boys? Please consider the processes leading up to college readiness and graduation, and diversity (racial/ethnic and/or social class) among students. Transition to Adulthood 1 Attachment for Day 2 Question B.1. New York Times Op-Ed Column October 9, 2007 David Brooks There used to be four common life phases: childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age. Now, there are at least six: childhood, adolescence, odyssey, adulthood, active retirement and old age. Of the new ones, the least understood is odyssey, the decade of wandering that frequently occurs between adolescence and adulthood. During this decade, 20-somethings go to school and take breaks from school. They live with friends and they live at home. They fall in and out of love. They try one career and then try another. Their parents grow increasingly anxious. These parents understand that there’s bound to be a transition phase between student life and adult life. But when they look at their own grown children, they see the transition stretching five years, seven and beyond. The parents don’t even detect a clear sense of direction in their children’s lives. They look at them and see the things that are being delayed. They see that people in this age bracket are delaying marriage. They’re delaying having children. They’re delaying permanent employment. People who were born before 1964 tend to define adulthood by certain accomplishments — moving away from home, becoming financially independent, getting married and starting a family. In 1960, roughly 70 percent of 30-year-olds had achieved these things. By 2000, fewer than 40 percent of 30-year-olds had done the same. Yet with a little imagination it’s possible even for baby boomers to understand what it’s like to be in the middle of the odyssey years. It’s possible to see that this period of improvisation is a sensible response to modern conditions. Two of the country’s best social scientists have been trying to understand this new life phase. William Galston of the Brookings Institution has recently completed a research project for the Hewlett Foundation. Robert Wuthnow of Princeton has just published a tremendously valuable book, “After the Baby Boomers” that looks at young adulthood through the prism of religious practice. Through their work, you can see the spirit of fluidity that now characterizes this stage. Young people grow up in tightly structured childhoods, Wuthnow observes, but then graduate into a world characterized by uncertainty, diversity, searching and tinkering. Old success recipes don’t apply, new norms have not been established and everything seems to give way to a less permanent version of itself. Transition to Adulthood 2 Dating gives way to Facebook and hooking up. Marriage gives way to cohabitation. Church attendance gives way to spiritual longing. Newspaper reading gives way to blogging. (In 1970, 49 percent of adults in their 20s read a daily paper; now it’s at 21 percent.) The job market is fluid. Graduating seniors don’t find corporations offering them jobs that will guide them all the way to retirement. Instead they find a vast menu of information economy options, few of which they have heard of or prepared for. Social life is fluid. There’s been a shift in the balance of power between the genders. Thirty-six percent of female workers in their 20s now have a college degree, compared with 23 percent of male workers. Male wages have stagnated over the past decades, while female wages have risen. This has fundamentally scrambled the courtship rituals and decreased the pressure to get married. Educated women can get many of the things they want (income, status, identity) without marriage, while they find it harder (or, if they’re working-class, next to impossible) to find a suitably accomplished mate. The odyssey years are not about slacking off. There are intense competitive pressures as a result of the vast numbers of people chasing relatively few opportunities. Moreover, surveys show that people living through these years have highly traditional aspirations (they rate parenthood more highly than their own parents did) even as they lead improvising lives. Rather, what we’re seeing is the creation of a new life phase, just as adolescence came into being a century ago. It’s a phase in which some social institutions flourish — knitting circles, Teach for America — while others — churches, political parties — have trouble establishing ties. But there is every reason to think this phase will grow more pronounced in the coming years. European nations are traveling this route ahead of us, Galston notes. Europeans delay marriage even longer than we do and spend even more years shifting between the job market and higher education. And as the new generational structure solidifies, social and economic entrepreneurs will create new rites and institutions. Someday people will look back and wonder at the vast social changes wrought by the emerging social group that saw their situations first captured by “Friends” and later by “Knocked Up.” Letter to the Editor of the New York Times Oct. 9, 2007 Laurence Steinberg, Temple University For young people from the upper-middle class, whose parents can afford to bankroll them while they experiment with careers, relationships and identities, the period between adolescence and adulthood may in fact be an odyssey of the sort that David Brooks has described. But research shows that this trend is far from universal, and before we accept the notion that a new stage of human development has emerged, it is informative to ask just how widespread it is. Transition to Adulthood 3 Recent empirical analyses indicate that about 40 percent of American young people follow this pattern. Poor inner-city and rural youth, as well as young people who live in the so-called red states, are far less likely than their advantaged, suburban and blue-state counterparts to delay the transition into conventional work and family roles, both because they choose not to and because they simply can't afford to. Perhaps over time, the odyssey stage will come to characterize the life course of the majority of young Americans, just as adolescence began as a middle-class institution and spread to less affluent groups, but it hasn't happened yet. Transition to Adulthood 4