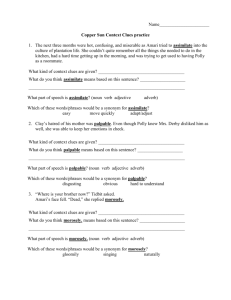

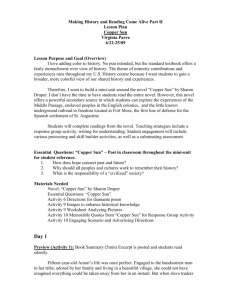

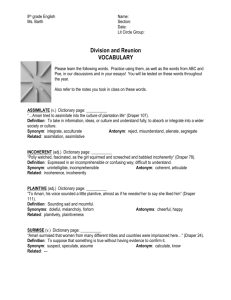

Part 1 Amari AMARI AND BESA “WHAT ARE YOU DOING UP

advertisement