Document

advertisement

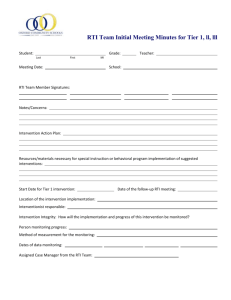

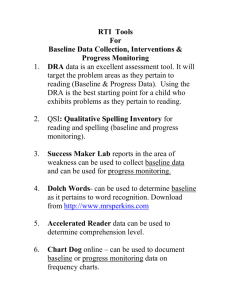

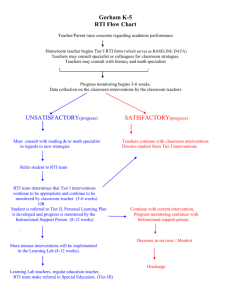

Response to Intervention Making RTI Work at the Middle and High School Levels Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Download PowerPoints and Handouts from this workshop at: http://www.interventioncentral.org/ NASP_Atlantic_City_2008.php www.interventioncentral.org 2 Response to Intervention Workshop Agenda… RTI & Secondary Schools: An Introduction The ‘Intervention Footprint’: Issues in Planning & Documentation Tier I: Promoting (Classroom) Interventions at the Secondary Level Tier II: Establishing an Effective RTI Problem-Solving Team RTI Assessment & Progress-Monitoring in Secondary Settings Empowering Students to Participate in Their Own RTI Plans RTI & Secondary Schools: Preparing for Systems-Level Change Next Steps: Creating an RTI Action Plan for Your School www.interventioncentral.org 3 Response to Intervention Discussion: Read the quote below: “The quality of a school as a learning community can be measured by how effectively it addresses the needs of struggling students.” --Wright (2005) Do you agree or disagree with this statement? Why? Source: Wright, J. (2005, Summer). Five interventions that work. NAESP Leadership Compass, 2(4) pp.1,6. www.interventioncentral.org 4 Response to Intervention Secondary Students: Unique Challenges… Struggling learners in middle and high school may: • Have significant deficits in basic academic skills • Lack higher-level problem-solving strategies and concepts • Present with issues of school motivation • Show social/emotional concerns that interfere with academics • Have difficulty with attendance • Are often in a process of disengaging from learning even as adults in school expect that those students will move toward being ‘self-managing’ learners… www.interventioncentral.org 5 Response to Intervention Why Do Students Drop Out of School?: Student Survey • • • • • • Classes were not perceived as interesting (47 percent) Not motivated by teachers to ‘work hard’ (69 percent) Failing in school was a major factor in dropping out (35 percent) Had to get a job (32 percent) Became a parent (26 percent) Needed to care for a family member (22 percent) Source: Bridgeland, J. M., DiIulio, J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. Seattle, WA: Gates Foundation. Retrieved on May 4, 2008, from http://www.gatesfoundation.org/nr/downloads/ed/TheSilentEpidemic3-06FINAL.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 6 Response to Intervention What Are Some Attributes of High Schools That Address the Needs of Struggling Learners? • Small schools (i.e., 400 students or fewer) • Well-articulated school mission that guides ‘development of a coherent curriculum’; unified approach to effective instruction across classrooms; and cohesive school culture • Strong relationships between staff and students • Close monitoring of student performance required for graduation and college eligibility • ‘Challenging and coherent instruction’: ‘High school standards, curricula, and textbooks are amile wide and an inch deep.’ • Relevant, functional ‘real-world’ application of instructional content and learning activities Source: Gates Foundation (n.d.). High schools for the new millenium: Imagine the possibilities. Retrieved on July 2, 2008, from http://www.gatesfoundation.org/nr/downloads/ed/edwhitepaper.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 7 Response to Intervention Overlap Between ‘Policy Pathways’ & RTI Goals: Recommendations for Schools to Reduce Dropout Rates • A range of high school learning options matched to the needs of individual learners: ‘different schools for different students’ • Strategies to engage parents • Individualized graduation plans • ‘Early warning systems’ to identify students at risk of school failure • A range of supplemental services/’intensive assistance strategies’ for struggling students • Adult advocates to work individually with at-risk students to overcome obstacles to school completion Source: Bridgeland, J. M., DiIulio, J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. Seattle, WA: Gates Foundation. Retrieved on May 4, 2008, from http://www.gatesfoundation.org/nr/downloads/ed/TheSilentEpidemic3-06FINAL.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 8 Response to Intervention Five Core Components of RTI Service Delivery 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Student services are arranged in a multi-tier model Data are collected to assess student baseline levels and to make decisions about student progress Interventions are ‘evidence-based’ The ‘procedural integrity’ of interventions is measured RTI is implemented and developed at the school- and district-level to be scalable and sustainable over time Source: Glover, T. A., & DiPerna, J. C. (2007). Service delivery for response to intervention: Core components and directions for future research. School Psychology Review, 36, 526-540. www.interventioncentral.org 9 Response to Intervention RTI ‘Pyramid of Interventions’ Tier III Tier II Tier I Tier III: Intensive interventions. Students who are ‘nonresponders’ to Tiers I & II may be eligible for special education services, intensive interventions. Tier II: Individualized interventions. Subset of students receive interventions targeting specific needs. An RTI Team may assist with the plan. Tier I: Universal interventions. Available to all students in a classroom or school. Can consist of whole-group or individual strategies or supports. www.interventioncentral.org 10 Response to Intervention Tier I Interventions Tier I interventions are universal—available to all students. Teachers often deliver these interventions in the classroom (e.g., providing additional drill and practice in reading fluency for students with limited decoding skills). Tier I interventions are those strategies that instructors are likely to put into place at the first sign that a student is struggling. Tier I interventions attempt to answer the question: Are routine classroom strategies for instructional delivery and classroom management sufficient to help the student to achieve academic success? www.interventioncentral.org 11 Response to Intervention Tier II Interventions Tier II interventions are individualized, tailored to the unique needs of struggling learners. They are reserved for students with significant skill gaps who have failed to respond successfully to Tier I strategies. Tier II interventions attempt to answer the question: Can an individualized intervention plan carried out in a general-education setting bring the student up to the academic level of his or her peers? www.interventioncentral.org 12 Response to Intervention Tier II Interventions There are two different vehicles that schools can use to deliver Tier II interventions: Standard-Protocol (Standalone Intervention). Group intervention programs based on scientifically valid instructional practices (‘standard protocol’) are created to address frequent student referral concerns. These services are provided outside of the classroom. A middle school, for example, may set up a structured math-tutoring program staffed by adult volunteer tutors to provide assistance to students with limited math skills. Students referred for a Tier II math intervention would be placed in this tutoring program. An advantage of the standard-protocol approach is that it is efficient and consistent: large numbers of students can be put into these group interventions to receive a highly standardized intervention. However, standard group intervention protocols often cannot be individualized easily to accommodate a specific student’s unique needs. Problem-solving (Classroom-Based Intervention). Individualized research-based interventions match the profile of a particular student’s strengths and limitations. The classroom teacher often has a large role in carrying out these interventions. A plus of the problem-solving approach is that the intervention can be customized to the student’s needs. However, developing intervention plans for individual students can be time-consuming. www.interventioncentral.org 13 Response to Intervention Tier III Interventions Tier III interventions are the most intensive academic supports available in a school and are generally reserved for students with chronic and severe academic delays or behavioral problems. In many schools, Tier III interventions are available only through special education. Tier III supports try to answer the question, What ongoing supports does this student require and in what settings to achieve the greatest success possible? www.interventioncentral.org 14 Response to Intervention Levels of Intervention: Tier I, II, & III Tier I: Universal 100% Tier II: Individualized 10-20% www.interventioncentral.org Tier III: Intensive 5-10% Response to Intervention RTI & Secondary Schools: A Walk on the ‘Wild’ Side www.interventioncentral.org 16 Response to Intervention RTI at the Secondary Level: ‘In a Perfect World’… Teachers are able and willing to individualize instruction in their classrooms to help struggling learners. The school has adequate programs and other supports for students with basic-skill deficits. The school can provide individualized problem-solving consultation for any struggling student. The progress of any student with an intervention plan is monitored frequently to determine if the plan is effective. Students are motivated to take part in intervention plans. www.interventioncentral.org 17 Response to Intervention RTI is a Model in Development “Several proposals for operationalizing response to intervention have been made…The field can expect more efforts like these and, for a time at least, different models to be tested…Therefore, it is premature to advocate any single model.” (Barnett, Daly, Jones, & Lentz, 2004 ) Source: Barnett, D. W., Daly, E. J., Jones, K. M., & Lentz, F.E. (2004). Response to intervention: Empirically based special service decisions from single-case designs of increasing and decreasing intensity. Journal of Special Education, 38, 66-79. www.interventioncentral.org 18 Response to Intervention Two Ways to Solve Problems: Algorithm vs. Heuristic • Algorithm. An explicit step-by-step procedure for producing a solution to a given problem. Example: Multiplying 6 x 2 • Heuristic. A rule of thumb or approach which may help in solving a problem, but is not guaranteed to find a solution. Heuristics are exploratory in nature. Example: Using a map to find an appropriate route to a location. www.interventioncentral.org 19 Response to Intervention MODERN DARYOLS RECIPE (ALGORITHM): As Knowledge Base Grows, Heuristic Approaches (Exploratory, Open-Ended Guidelines to Solving a Problem) Can Sometimes Turn into Algorithms (Fixed Rules for Solving a Problem ) Example: Recipes Through History DARYOLS: ORIGINAL14th CENTURY ENGLISH RECIPE (HEURISTIC): Take cream of cow milk, or of almonds; do there-to eggs with sugar, saffron and salt. Mix it fair. Do it in a pie shell of 2 inch deep; bake it well and serve it forth. INGREDIENTS 2 (9 inch) unbaked pie crusts 1 1/4 cups cold water 1 pinch saffron powder 5 eggs 1 teaspoon rose water 1/2 cup blanched almonds 1 cup half-and-half cream 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon 3/4 cup white sugar DIRECTIONS Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F (175 degrees C). Press pie crusts into the bottom and up the sides of two 9 inch pie pans. Prick with a fork all over to keep them from bubbling up. Bake pie crusts for about 10 minutes in the preheated oven, until set but not browned. Set aside to cool. Make an almond milk by placing almonds in the container of a food processor. Process until finely ground, then add water, and pulse just to blend. Let the mixture sit for 10 minutes, then strain through a cheesecloth. Measure out 1 cup of the almond milk, and mix with half and half. Stir in the saffron and cinnamon, and set aside. Place the eggs and sugar in a saucepan, and mix until well blended. Place the pan over low heat, and gradually stir in the almond milk mixture and cinnamon. Cook over low heat, stirring constantly until the mixture begins to thicken. When the mixture is thick enough to evenly coat the back of a metal spoon, stir in rose water and remove from heat. Pour into the cooled pie shells…. Bake for 40 minutes in the preheated oven, or until the center is set, but the top is not browned. Cool to room temperature, then refrigerate until serving. www.interventioncentral.org 20 Response to Intervention RTI is a Work in Progress: Some Areas Can Be Managed Like an Algorithm While Others Require a Heuristic Approch • Reading Fluency. Can be approached as a fixed algorithm. – DIBELS allows universal screening and progress-monitoring – DIBELS benchmarks give indication of student risk status – Classroom-friendly research-based fluency building interventions have been validated • Study Skills. A complex set of skills whose problem-solving approach resembles a heuristic. – Student’s basic set of study skills must be analyzed – The intervention selected will be highly dependent on the hypothesized reason(s) for the student’s study difficulties – The quality of the research on study-skills interventions varies and is still in development www.interventioncentral.org 21 Response to Intervention “RTI implementation has clearly focused on elementary grades, with few attempting it on the secondary level…However, school districts will need to decide when and how—rather than if—RTI will begin in their middle schools and high schools. We suggest focusing on elementary schools in the initial phase of implementation, but eventually including secondary schools in practice and throughout the planning process.” -- Burns & Gibbons (2008) p. 10 Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools: Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org 22 Response to Intervention RTI: Research Questions Q: How Relevant is RTI to Secondary Schools? The purposes of RTI have been widely defined as: • Early intervention in general education • Special education disability determination How relevant is RTI at the middle or high school level? Source: Fuchs, D., & Deshler, D. D. (2007). What we need to know about responsiveness to intervention (and shouldn’t be afraid to ask).. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(2),129–136. www.interventioncentral.org 23 Response to Intervention The Purpose of RTI in Secondary Schools: What Students Does It Serve? While the dual use of the RTI model (1) for early identification/remediation of at-risk students and (2) for the classification of children needing special education is adequate for the elementary level, in middle and high school there are also significant numbers of students who have a long history of poor school performance yet will probably not quality for special education services. In secondary schools, RTI must expand its mission to help chronically struggling, unmotivated students in a systematic way. In particular, how does RTI manage the needs of the chronically underachieving secondary student who does not (and likely will not) qualify for special education but requires ongoing academic support? www.interventioncentral.org 24 Response to Intervention The Purpose of RTI in Secondary Schools: What Students Should It Serve? Early Identification. As students begin to show need for academic support, the RTI model proactively supports them with early interventions to close the skill or performance gap with peers. Chronically At-Risk. Students whose school performance is marginal across school years but who do not qualify for special education services are identified by the RTI Team and provided with ongoing intervention support. www.interventioncentral.org Special Education. Students who fail to respond to scientifically valid general-education interventions implemented with integrity are classified as ‘non-responders’ and found eligible for special education. 25 Response to Intervention Measuring the ‘Intervention Footprint’: Issues of Planning, Documentation, & Follow-Through Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Elements of an Effective Intervention Plan (Grimes & Kurns, 2003) “Intervention design and implementation. Interventions are designed based on [a thorough] analysis, the defined problem, parent input, and professional judgments about the potential effectiveness of interventions. The interventions are described in an intervention plan that includes goals and strategies; a progress monitoring plan; a decision-making plan for summarizing and analyzing progress monitoring data; and responsible parties. Interventions are implemented as developed and modified on the basis of objective data and with the agreement of the responsible parties.” Source: Grimes, J. & Kurns, S. (2003). An intervention-based system for addressing NCLB and IDEA expectations: A multiple tiered model to ensure every child learns. Retrieved on September 23, 2007, from http://www.nrcld.org/symposium2003/grimes/grimes2.html www.interventioncentral.org 27 Response to Intervention Essential Elements of Any Academic or Behavioral Intervention (‘Treatment’) Strategy: • Method of delivery (‘Who or what delivers the treatment?’) Examples include teachers, paraprofessionals, parents, volunteers, computers. • Treatment component (‘What makes the intervention effective?’) Examples include activation of prior knowledge to help the student to make meaningful connections between ‘known’ and new material; guide practice (e.g., Paired Reading) to increase reading fluency; periodic review of material to aid student retention. As an example of a research-based commercial program, Read Naturally ‘combines teacher modeling, repeated reading and progress monitoring to remediate fluency problems’. Source: Yeaton, W. H. & Sechrest, L. (1981). Critical dimensions in the choice and maintenance of successful treatments: Strength, integrity, and effectiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 156-167. www.interventioncentral.org 28 Response to Intervention Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Interventions. An academic intervention is a strategy used to teach a new skill, build fluency in a skill, or encourage a child to apply an existing skill to new situations or settings. An intervention is said to be research-based when it has been demonstrated to be effective in one or more articles published in peer–reviewed scientific journals. Interventions might be based on commercial programs such as Read Naturally. The school may also develop and implement an intervention that is based on guidelines provided in research articles—such as Paired Reading (Topping, 1987). www.interventioncentral.org 29 Response to Intervention Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Accommodations. An accommodation is intended to help the student to fully access the general-education curriculum without changing the instructional content. An accommodation for students who are slow readers, for example, may include having them supplement their silent reading of a novel by listening to the book on tape. An accommodation is intended to remove barriers to learning while still expecting that students will master the same instructional content as their typical peers. Informal accommodations may be used at the classroom level or be incorporated into a more intensive, individualized intervention plan. www.interventioncentral.org 30 Response to Intervention Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Modifications. A modification changes the expectations of what a student is expected to know or do—typically by lowering the academic expectations against which the student is to be evaluated. Examples of modifications are reducing the number of multiple-choice items in a test from five to four or shortening a spelling list. Under RTI, modifications are generally not included in a student’s intervention plan, because the working assumption is that the student can be successful in the curriculum with appropriate interventions and accommodations alone. www.interventioncentral.org 31 Response to Intervention Evaluating the Quality of Intervention Research: The ‘Research Continuum’ www.interventioncentral.org 32 Response to Intervention Intervention ‘Research Continuum’ Evidence-Based Practices “Includes practices for which original data have been collected to determine the effectiveness of the practice for students with disabilities. The research utilizes scientifically based rigorous research designs (i.e., randomized controlled trials, regression discontinuity designs, quasi-experiments, single subject, and qualitative research).” Source: The Access Center Research Continuum (n.d.). Retrieved on June 1, 2008 from http://www.k8accesscenter.org/training_resources/documents/ACResearchApproachFormatted.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 33 Response to Intervention Intervention ‘Research Continuum’ Promising Practices “Includes practices that were developed based on theory or research, but for which an insufficient amount of original data have been collected to determine the effectiveness of the practices. Practices in this category may have been studied, but not using the most rigorous study designs.” Source: The Access Center Research Continuum (n.d.). Retrieved on June 1, 2008 from http://www.k8accesscenter.org/training_resources/documents/ACResearchApproachFormatted.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 34 Response to Intervention Intervention ‘Research Continuum’ Emerging Practices “Includes practices that are not based on research or theory and on which original data have not been collected, but for which anecdotal evidence and professional wisdom exists. These include practices that practitioners have tried and feel are effective and new practices or programs that have not yet been researched.” Source: The Access Center Research Continuum (n.d.). Retrieved on June 1, 2008 from http://www.k8accesscenter.org/training_resources/documents/ACResearchApproachFormatted.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 35 Response to Intervention Writing Quality ‘Problem Identification’ Statements www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Writing Quality ‘Problem Identification’ Statements • A frequent problem at RTI Team meetings is that teacher referral concerns are written in vague terms. If the referral concern is not written in explicit, observable, measurable terms, it will be very difficult to write clear goals for improvement or select appropriate interventions. • Use this ‘test’ for evaluating the quality of a problemidentification (‘teacher-concern’) statement: Can a third party enter a classroom with the problem definition in hand and know when they see the behavior and when they don’t? www.interventioncentral.org 37 Response to Intervention Writing Quality ‘Problem-Identification’ Statements: Template Format for Writing RTI Team Teacher Concerns Conditions when the behavior is observed or absent Description of behavior in concrete, measurable, observable terms During large-group instruction The student calls out comments that do not relate to the content being taught. When reading aloud The student decodes at a rate much slower than classmates. When sent from the classroom with a pass to perform an errand or take a bathroom break The student often wanders the building instead of returning promptly to class. www.interventioncentral.org 38 Response to Intervention Writing Quality ‘Teacher Referral Concern’ Statements: Examples • Needs Work: The student is disruptive. • Better: During independent seatwork , the student is out of her seat frequently and talking with other students. • Needs Work: The student doesn’t do his math. • Better: When math homework is assigned, the student turns in math homework only about 20 percent of the time. Assignments turned in are often not fully completed. www.interventioncentral.org 39 Response to Intervention Evaluating ‘Intervention Follow-Through’ (Treatment Integrity) www.interventioncentral.org 40 Response to Intervention Why Monitor Intervention Follow-Through? If the RTI Team does not monitor the quality of the intervention follow-through, it will not know how to explain a student’s failure to ‘respond to intervention’. • Do qualities within the student explain the lack of academic or behavioral progress? • Did problems with implementing the intervention prevent the student from making progress? www.interventioncentral.org 41 Response to Intervention What Are Potential Barriers to Assessing Intervention Follow-Through? Direct observation of interventions is the ‘gold standard’ for evaluating the quality of their implementation. However: • Teachers being observed may feel that they are being evaluated for global job performance • Non-administrative staff may be uncomfortable observing a fellow educator to evaluate intervention follow-through • It can be difficult for staff to find time to observe and evaluate interventions as they are being carried out www.interventioncentral.org 42 Response to Intervention Supplemental Ideas to Collect Information About Classroom Implementation of Interventions • Assign a ‘case manager’ from the RTI Intervention Team to check in with the teacher within a week of the initial meeting to see how the intervention is going. • Have the teacher use a data tool to collect information about the student’s response to intervention (e.g., Daily Behavior Report Card) or about the implementation of the intervention itself (e.g. Teacher Intervention Evaluation Log) • Include a scripted question at the RTI Intervention Team Follow-Up Meeting that explicitly asks the referring teacher or instructional team to provide details about the implementation of the intervention. • Leave a notebook in the classroom for the teacher to jot down any questions or concerns about the intervention. Assign an RTI Team member to stop by the classroom periodically to check the notebook and respond to any concerns noted. www.interventioncentral.org 43 Response to Intervention Tier II ‘Standard Protocol’ Interventions in the Middle or High School www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention RTI ‘Pyramid of Interventions’ Tier III Tier II Tier I Tier III: Intensive interventions. Students who are ‘nonresponders’ to Tiers I & II may be eligible for special education services, intensive interventions. Tier II: Individualized interventions. Subset of students receive interventions targeting specific needs. An RTI Team may assist with the plan. Tier I: Universal interventions. Available to all students in a classroom or school. Can consist of whole-group or individual strategies or supports. www.interventioncentral.org 45 Response to Intervention Tier II Interventions Tier II interventions are individualized, tailored to the unique needs of struggling learners. They are reserved for students with significant skill gaps who have failed to respond successfully to Tier I strategies. Tier II interventions attempt to answer the question: Can an individualized intervention plan carried out in a general-education setting bring the student up to the academic level of his or her peers? www.interventioncentral.org 46 Response to Intervention Tier II Interventions There are two different vehicles that schools can use to deliver Tier II interventions: Standard-Protocol (Standalone Intervention). Group intervention programs based on scientifically valid instructional practices (‘standard protocol’) are created to address frequent student referral concerns. These services are provided outside of the classroom. A middle school, for example, may set up a structured math-tutoring program staffed by adult volunteer tutors to provide assistance to students with limited math skills. Students referred for a Tier II math intervention would be placed in this tutoring program. An advantage of the standard-protocol approach is that it is efficient and consistent: large numbers of students can be put into these group interventions to receive a highly standardized intervention. However, standard group intervention protocols often cannot be individualized easily to accommodate a specific student’s unique needs. Problem-solving (Classroom-Based Intervention). Individualized research-based interventions match the profile of a particular student’s strengths and limitations. The classroom teacher often has a large role in carrying out these interventions. A plus of the problem-solving approach is that the intervention can be customized to the student’s needs. However, developing intervention plans for individual students can be time-consuming. www.interventioncentral.org 47 Response to Intervention Tier II Individual Student Intervention Plans Can Have Several Components • ‘Pull-Out’: Student receives the intervention in a separate group or during a class period. • Classroom: Content-area teachers implement classroomappropriate interventions. • Push-In: An adult (e.g., helping teacher, paraprofessional) pushes into the classroom setting to provide intervention support. • Student-Directed: The student is responsible for accessing elements of the intervention plan such as seeking extra teacher help during ‘drop-in’ periods. www.interventioncentral.org 48 Response to Intervention 7-Step ‘Lifecycle’ of a Tier II Intervention Plan… 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Information about the student’s academic or behavioral concerns is collected. The intervention plan is developed to match student presenting concerns. Preparations are made to implement the plan. The plan begins. The integrity of the plan’s implementation is measured. Formative data is collected to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness. The plan is discontinued, modified, or replaced. www.interventioncentral.org 49 Response to Intervention Caution About Secondary Tier II Standard-Protocol Interventions: Avoid the ‘Homework Help’ Trap • Tier II group-based or standard-protocol interventions are an efficient method to deliver targeted academic support to students (Burns & Gibbons, 2008). • However, students should be matched to specific research-based interventions that address their specific needs. • RTI intervention support in secondary schools should not take the form of unfocused ‘homework help’. www.interventioncentral.org 50 Response to Intervention Traditional Schedule: Tier II Intervention Delivery for ‘Standard Protocol’ Interventions • Class length of 50-60 minutes • 6-8 classes per day • Typical solution: Students are scheduled for a remedial course. Drawbacks to this solution are that students may not receive targeted instruction, the teacher has large numbers of students, and students cannot exit the course before the end of the school year. • Tier II Recommendation (Burns & Gibbon, 2008): Pair a reading interventionist with the content-area teacher. The reading teacher can provide remedial instruction to rotating small groups (e.g, 7-8 students) for 30 minute periods while the content-area teacher provides whole-group instruction to the rest of the class. Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools: Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org 51 Response to Intervention Block Schedule: Tier II Intervention Delivery for ‘Standard Protocol’ Interventions • Class length of 1.5 to 2 hours • Four classes per day • Alternating schedule to accommodate full roster of classes in a year (either alternating days –AB– or alternating semesters—’4 X 4’) • Tier II Recommendation (Burns & Gibbon, 2008): Pair a reading interventionist with the content-area teacher. The reading teacher can provide remedial instruction to rotating small groups (e.g, 7-8 students) for 30 minute periods while the content-area teacher provides whole-group instruction to the rest of the class. Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools: Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org 52 Response to Intervention How Do We Define a Tier I (Classroom-Based) Intervention? Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention RTI: Research Questions Q: What is the nature of Tier I Instruction? There is a lack of agreement about what we mean by ‘scientifically validated’ classroom (Tier I) interventions. Districts should establish a ‘vetting’ process—criteria for judging whether a particular instructional or intervention approach should be considered empirically based. Source: Fuchs, D., & Deshler, D. D. (2007). What we need to know about responsiveness to intervention (and shouldn’t be afraid to ask).. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(2),129–136. www.interventioncentral.org 54 Response to Intervention Tier I Interventions Tier I interventions are universal—available to all students. Teachers often deliver these interventions in the classroom. Tier I interventions are those strategies that instructors are likely to put into place at the first sign that a student is struggling. These interventions can consist of: -Effective ‘whole-group’ teaching & management strategies -Modest individualized strategies that the teacher uses with specific students. Tier I interventions attempt to answer the question: Are routine classroom instructional strategies sufficient to help the student to achieve academic success? www.interventioncentral.org 55 Response to Intervention Examples of Evidence-Based Tier I Management Strategies (Fairbanks, Sugai, Guardino, & Lathrop, 2007) • • • • Consistently acknowledging appropriate behavior in class Providing students with frequent and varied opportunities to respond during instructional activities Reducing transition time between instructional activities to a minimum Giving students immediate and direct corrective feedback when they commit an academic error or engage in inappropriate behavior Source: Fairbanks, S., Sugai, G., Guardino, S., & Lathrop, M. (2007). Response to intervention: Examining classroom behavior support in second grade. Exceptional Children, 73, p. 290. www.interventioncentral.org 56 Response to Intervention Tier I Ideas to Help Students to Complete Independent Seatwork www.interventioncentral.org 57 Response to Intervention Independent Seatwork: A Source of Misbehavior When poorly achieving students must work independently, they can run into difficulties with the potential to spiral into misbehaviors. These difficulties can include: • Being unable to do the assigned work without help • Not understanding the directions for the assignment • Getting stuck during the assignment and not knowing how to resolve the problem • Being reluctant to ask for help in a public manner • Lacking motivation to work independently on the assignment www.interventioncentral.org 58 Response to Intervention Elements to Support Independent Seatwork Directions & Instructional Match. The teacher ensures that Performance Feedback. The student can access an answer key (if appropriate) to check his or her work. the student understands the assignment and can do the work. Reference Sheets. The student has a reference sheet with steps to follow to complete the assignment or other needed information. Completed Models. The student has one or more models of correctly completed assignment items for reference. Help Routine. The student knows how to request help without drawing attention (e.g., by asking a peer). www.interventioncentral.org Teacher Feedback & Encouragement. The teacher circulates around the room (proximity) , spending brief amounts of time checking students’ progress and giving feedback and encouragement as needed. 59 Response to Intervention Building Positive Relationships With Students Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Avoiding the ‘Reprimand Trap’ When working with students who display challenging behaviors, instructors can easily fall into the ‘reprimand trap’. In this sequence: 1. 2. 3. The student misbehaves. The teacher approaches the student to reprimand and redirect. (But the teacher tends not to give the student attention for positive behaviors, such as paying attention and doing school work.) As the misbehave-reprimand pattern becomes ingrained, both student and teacher experience a strained relationship and negative feelings. www.interventioncentral.org 61 Response to Intervention Sample Ideas to Improve Relationships With Students: The Two-By-Ten Intervention (Mendler, 2000) • Make a commitment to spend 2 minutes per day for 10 consecutive days in building a relationship with the student…by talking about topics of interest to the student. Avoid discussing problems with the student’s behaviors or schoolwork during these times. Source: Mendler, A. N. (2000). Motivating students who don’t care. Bloomington, IN: National Educational Service. www.interventioncentral.org 62 Response to Intervention Sample Ideas to Improve Relationships With Students: The Three-to-One Intervention (Sprick, Borgmeier, & Nolet, 2002) • Give positive attention or praise to problem students at least three times more frequently than you reprimand them. Give the student the attention or praise during moments when that student is acting appropriately. Keep track of how frequently you give positive attention and reprimands to the student. Source: Sprick, R. S., Borgmeier, C., & Nolet, V. (2002). Prevention and management of behavior problems in secondary schools. In M. A. Shinn, H. M. Walker & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp.373-401). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. www.interventioncentral.org 63 Response to Intervention Discussion Question Why would a teacher at your school be very happy to see an RTI model adopted? What is in it for him or her? www.interventioncentral.org 64 Response to Intervention How Do Schools ‘Standardize’ Expectations for Tier I Interventions? A Four-Step Solution 1. 2. 3. 4. Develop a list of your school’s ‘top five’ academic and behavioral referral concerns (e.g., low reading fluency, inattention). Create a survey for teachers, asking them to jot down the ‘good teaching’ ideas that they use independently when they encounter students who struggle in these problem areas. Collect the best of these ideas into a menu. Add additional research-based ideas if available. Require that teachers implement a certain number of these strategies before referring to your RTI Intervention Team. Consider ways that teachers can document these Tier I interventions as well. www.interventioncentral.org 65 Response to Intervention RTI Intervention Teams in Middle & High Schools: Challenges and Opportunities Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Tier II Interventions There are two different vehicles that schools can use to deliver Tier II interventions: Standard-Protocol (Standalone Intervention). Group intervention programs based on scientifically valid instructional practices (‘standard protocol’) are created to address frequent student referral concerns. These services are provided outside of the classroom. A middle school, for example, may set up a structured math-tutoring program staffed by adult volunteer tutors to provide assistance to students with limited math skills. Students referred for a Tier II math intervention would be placed in this tutoring program. An advantage of the standard-protocol approach is that it is efficient and consistent: large numbers of students can be put into these group interventions to receive a highly standardized intervention. However, standard group intervention protocols often cannot be individualized easily to accommodate a specific student’s unique needs. Problem-solving (Classroom-Based Intervention). Individualized research-based interventions match the profile of a particular student’s strengths and limitations. The classroom teacher often has a large role in carrying out these interventions. A plus of the problem-solving approach is that the intervention can be customized to the student’s needs. However, developing intervention plans for individual students can be time-consuming. www.interventioncentral.org 67 Response to Intervention The RTI Team: Definition • Teams of educators at a school are trained to work together as effective problem-solvers. • RTI Teams are made up of volunteers drawn from generaland special-education teachers and support staff. • These teams use a structured meeting process to identify the underlying reasons that a student might be experiencing academic or behavioral difficulties • The team helps the referring teacher to put together practical, classroom-friendly interventions to address those student problems. www.interventioncentral.org 68 Response to Intervention The Problem-Solving Model & Multi-Disciplinary Teams A school consultative process (‘the problem-solving model’) with roots in applied behavior analysis was developed (Bergan, 1995) that includes 4 steps: – Problem Identification – Problem Analysis – Plan Implementation – Problem Evaluation Originally designed for individual consultation with teachers, the problem-solving model was later adapted in various forms to multi-disciplinary team settings. Source: Bergan, J. R. (1995). Evolution of a problem-solving model of consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 6(2), 111-123. www.interventioncentral.org 69 Response to Intervention RTI: Research Questions Q: Does a ‘Problem-Solving’ Multi-Disciplinary Team Process Help Children With Severe Learning Problems? The team-based ‘problem-solving’ process (e.g., Bergan, 1995) that is widely used to create individualized intervention plans for students has been studied primarily for motivation and conduct issues. There is limited research on whether the problem-solving process is effective in addressing more significant learning issues. Source: Bergan, J. R. (1995). Evolution of a problem-solving model of consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 6(2), 111-123. Fuchs, D., & Deshler, D. D. (2007). What we need to know about responsiveness to intervention (and shouldn’t be afraid to ask).. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(2),129–136. www.interventioncentral.org 70 Response to Intervention RTI Problem-Solving Teams at the Secondary Level: The Necessary Art of ‘Satisficing’ “The word satisfice was coined by Herbert Simon as a portmanteau of "satisfy" and "suffice". Simon pointed out that human beings lack the cognitive resources to maximize: we usually do not know the relevant probabilities of outcomes, we can rarely evaluate all outcomes with sufficient precision, and our memories are weak and unreliable. A more realistic approach to rationality takes into account these limitations: This is called bounded rationality.” (Satisficing, 2008) Source: Satisficing (2008). Wikipedia. Retrieved on July 2, 2008, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satisficing www.interventioncentral.org 71 Response to Intervention How Is a Secondary RTI Team Like a MASH Unit? • The RTI Team must deal with complex situations with limited resources and tight timelines, often being forced to select from among numerous ‘intervention targets’ (e.g., attendance, motivation, basic skill deficits, higherlevel deficits in cognitive strategies) when working with struggling students. • The ‘problem-solving’ approach is flexible, allowing the RTI Team quickly to sift through a complex student case to identify and address the most important ‘blockers’ to academic success. • Timelines for success are often short-term (e.g., to get the student to pass a course or a state test), measured in weeks or months. www.interventioncentral.org 72 Response to Intervention Teachers may be reluctant to refer students to the RTI Team because they… • believe referring to the RTI Team is a sign of failure • do not think that your team has any ideas that they haven’t already tried • believe that an RTI Team referral will mean a lot more work for them (vs. referring directly to Special Education) • don’t want to ‘waste time’ on kids with poor motivation or behavior problems when ‘more deserving’ learners go unnoticed and unrewarded • don’t want to put effort into learning a new initiative that may just fade away in a couple of years www.interventioncentral.org 73 Response to Intervention Teachers may be motivated to refer students to the RTI Team because they… • can engage in collegial conversations about better ways to help struggling learners • learn instructional and behavior-management strategies that they can use with similar students in the future • increase their teaching time • are able to access more intervention resources and supports in the building than if they work alone • feel less isolated when dealing with challenging kids • have help in documenting their intervention efforts www.interventioncentral.org 74 Response to Intervention Team Roles (pp. 23-24) • • • • • Coordinator Facilitator Recorder Time Keeper Case Manager www.interventioncentral.org 75 Response to Intervention RTI Team Consultative Process (pp. 9-13) Step 1: Assess Teacher Concerns 5 Mins Step 2: Inventory Student Strengths/Talents 5 Mins Step 3: Review Background/Baseline Data 5 Mins Step 4: Select Target Teacher Concerns 5-10 Mins Step 5: Set Academic and/or Behavioral Outcome Goals and Methods for Progress-Monitoring 5 Mins Step 6: Design an Intervention Plan 15-20 Mins Step 7: Plan How to Share Meeting Information with the Student’s Parent(s) 5 Mins Step 8: Review Intervention & Monitoring Plans 5 Mins www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Small-Group Activity: Complete the RTI Team Effectiveness Self-Rating Scale • As a group, use the RTI Team Self-Rating Scale to evaluate your current team’s level of functioning. • Appoint a spokesperson to share your findings with the large group. www.interventioncentral.org 77 Response to Intervention Monitoring Student Progress at the Secondary Level Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention “Everybody is entitled to their own opinion but they’re not entitled to their own facts. The data is the data.” Dr. Maria Spiropulu, Physicist New York Times, 30 September 2003 (D. Overbye) Other dimensions? She’s in pursuit. F1, F4 www.interventioncentral.org 79 Response to Intervention “Few agree on an appropriate curriculum for secondary students…; thus it is difficult to determine in what areas student [academic] progress should be measured.” -- Espin & Tindal (1998) Source: Espin, C. A., & Tindal, G. (1998). Curriculum-based measurement for secondary students. In M. R. Shinn (Ed.) Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 80 Response to Intervention RTI: Research Questions Q: What RTI Identification Method Will Best Determine What Students Are ‘Responders’ or ‘Non-Responders’ to Intervention? There are several methods in the research literature to determine ‘non-responders’ to intervention (e.g., dual discrepancy, slope discrepancy). What is the ‘best’ method to reliably differentiate students who do or do Source:not Fuchs, D., & Deshler, D. D. (2007). What weinterventions? need to know about responsiveness to intervention (and shouldn’t be respond to RTI afraid to ask).. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(2),129–136. www.interventioncentral.org 81 Response to Intervention Secondary Students: Should Interventions Be ‘OffLevel’ or Focus on Grade-Level Academics? There is a lack of consensus about how to address the academic needs of students with deficits in basic skills in secondary grades (Espin & Tindal, 1998). – Should the student be placed in remedial instruction at a point of ‘instructional match’ to address those basic-skill deficits? (Instruction adjusted down to the student) – Or is time better spent providing the student with compensatory strategies to learn grade-level content and ‘work around’ those basic-skill deficits? (Student Source: Espin, is C. A., & Tindal, G. (1998). Curriculum-based measurement for secondary students. In M. R. Shinn (Ed.) Advanced brought up to current instruction) applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 82 Response to Intervention Remediating Academic Deficits: The Widening Curriculum Gap… Widening academic Largest academic gap (middle school).(high school). Student is Smallgap academic Student is significantly off-level. The gap (elementary significantly school). Student off-level. building curriculum does building not overlap the student’s is onlyThe mildly offbarely point of ‘instructional level.curriculum The overlaps the student’smatch’ at all. building Reading Fluency Rdng-Basic Comprehension Reading Fluency point of ‘instructional curriculum match’. overlaps the student’s point of Subject-Area Rdng Comprehension ‘instructional match’. Rdng-Basic Comprehension Rdng Fluency K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 www.interventioncentral.org 83 Response to Intervention Measuring General vs. Specific Academic Outcomes • General Outcome Measures: Track the student’s increasing proficiency on general curriculum goals such as reading fluency. An example is CBM-Oral Reading Fluency (Hintz et al., 2006). • Specific Sub-Skill Mastery Measures: Track short-term student academic progress with clear criteria for mastery. An example is CBA-Math Computation Fluency (Burns & Gibbons, 2008). Sources: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools: Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. Hintz, J. M., Christ, T. J., & Methe, S. A. (2006). Curriculum-based assessment. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 45-56. www.interventioncentral.org 84 Response to Intervention Making Use of Existing (‘Extant’) Data www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Extant (Existing) Data (Chafouleas et al., 2007) • Definition: Information that is collected by schools as a matter of course. • Extant data comes in two forms: – Performance summaries (e.g., class grades, teacher summary comments on report cards, state test scores). – Student work products (e.g., research papers, math homework, PowerPoint presentation). Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 86 Response to Intervention Summative data is static information that provides a fixed ‘snapshot’ of the student’s academic performance or behaviors at a particular point in time. School records are one source of data that is often summative in nature—frequently referred to as archival data. Attendance data and office disciplinary referrals are two examples of archival records, data that is routinely collected on all students. In contrast to archival data, background information is collected specifically on the target student. Examples of background information are teacher interviews and student interest surveys, each of which can shed light on a student’s academic or behavioral strengths and weaknesses. Like archival data, background information is usually summative, providing a measurement of the student at a single point in time. www.interventioncentral.org 87 Response to Intervention Formative assessment measures are those that can be administered or collected frequently—for example, on a weekly or even daily basis. These measures provide a flow of regularly updated information (progress monitoring) about the student’s progress in the identified area(s) of academic or behavioral concern. Formative data provide a ‘moving picture’ of the student; the data unfold through time to tell the story of that student’s response to various classroom instructional and behavior management strategies. Examples of measures that provide formative data are CurriculumBased Measurement probes in oral reading fluency and Daily Behavior Report Cards. www.interventioncentral.org 88 Response to Intervention Advantages of Using Extant Data (Chafouleas et al., 2007) • Information is already existing and easy to access. • Students are less likely to show ‘reactive’ effects when data is collected, as the information collected is part of the normal routine of schools. • Extant data is ‘relevant’ to school data consumers (such as classroom teachers, administrators, and members of problem-solving teams). Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 89 Response to Intervention Drawbacks of Using Extant Data (Chafouleas et al., 2007) • Time is required to collate and summarize the data (e.g., summarizing a week’s worth of disciplinary office referrals). • The data may be limited and not reveal the full dimension of the student’s presenting problem(s). • There is no guarantee that school staff are consistent and accurate in how they collect the data (e.g., grading policies can vary across classrooms; instructors may have differing expectations regarding what types of assignments are given a formal grade; standards may fluctuate across teachers for filling out disciplinary referrals). • Little research has been done on the ‘psychometric Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford adequacy’ of Press. extantwww.interventioncentral.org data sources. 90 Response to Intervention ‘Elbow Group’ Activity: What Data Should Be Collected for RTI Team Meetings? What are the ‘essential’ sources of archival data that you would like collected and brought to every RTI Problem-Solving Team meeting? www.interventioncentral.org 91 Response to Intervention Grades as a Classroom-Based ‘Pulse’ Measure of Academic Performance www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Grades & Other Teacher Performance Summary Data (Chafouleas et al., 2007) • Teacher test and quiz grades can be useful as a supplemental method for monitoring the impact of student behavioral interventions. • Other data about student academic performance (e.g., homework completion, homework grades, etc.) can also be tracked and graphed to judge intervention effectiveness. Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 93 Response to Intervention Marc Ripley 2-Wk 9/23/07 4-Wk 10/07/07 6-Wk 10/21/07 (From Chafouleas et al., 2007) 8-Wk 11/03/07 10-Wk 11/20/07 12-Wk 12/05/07 Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 94 Response to Intervention Assessing Basic Academic Skills: CurriculumBased Measurement www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Assessing Basic Academic Skills: Curriculum-Based Measurement Reading: These 3 measures all proved ‘adequate predictors’ of student performance on reading content tasks: – Reading aloud (Oral Reading Fluency): Passages from content-area tests: 1 minute. – Maze task (every 7th item replaced with multiple choice/answer plus 2 distracters): Passages from content-area texts: 2 minutes. – Vocabulary matching: 10 vocabulary items and 12 definitions (including 2 distracters): 10 minutes. Source: Espin, C. A., & Tindal, G. (1998). Curriculum-based measurement for secondary students. In M. R. Shinn (Ed.) Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 96 Response to Intervention Assessing Basic Academic Skills: Curriculum-Based Measurement Mathematics: Single-skill basic arithmetic combinations an ‘adequate measure of performance’ for low-achieving middle school students. •www.interventioncentral.org Websites to create CBM math computation probes: •www.superkids.com Source: Espin, C. A., & Tindal, G. (1998). Curriculum-based measurement for secondary students. In M. R. Shinn (Ed.) Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford Press. www.interventioncentral.org 97 Response to Intervention Assessing Basic Academic Skills: Curriculum-Based Measurement Writing: CBM/ Word Sequence is a ‘valid indicator of general writing proficiency’. It evaluates units of writing and their relation to one another. Successive pairs of ‘writing units’ make up each word sequence. The mechanics and conventions of each word sequence must be correct for the student to receive credit for that CBM/ Word Sequence Source: Espin, C. sequence. A., & Tindal, G. (1998). Curriculum-based measurement for secondary students. In M. R. Shinn (Ed.) Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford Press. is the most comprehensive CBM writing www.interventioncentral.org 98 Response to Intervention A Note About Monitoring Behaviors Through Academic Measures… Academic measures (e.g., grades, CBM data) can be useful as part of the progress-monitoring ‘portfolio’ of data collected on a student because: • Students with problem behaviors often struggle academically, so tracking academics as a target is justified in its own right. • Improved academic performance generally correlates with reduced behavioral problems. • Individualized interventions for misbehaving students frequently contain academic components (as the behavior problems can emerge in response to chronic academic deficits).www.interventioncentral.org Academic progress-monitoring 99 Response to Intervention Breaking Down Complex Academic Goals into Simpler Sub-Tasks: Discrete Categorization www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Identifying and Measuring Complex Academic Problems at the Middle and High School Level • Students at the secondary level can present with a range of concerns that interfere with academic success. • One frequent challenge for these students is the need to reduce complex global academic goals into discrete sub-skills that can be individually measured and tracked over time. www.interventioncentral.org 101 Response to Intervention Discrete Categorization: A Strategy for Assessing Complex, Multi-Step Student Academic Tasks Definition of Discrete Categorization: ‘Listing a number of behaviors and checking off whether they were performed.’ (Kazdin, 1989, p. 59). • Approach allows educators to define a larger ‘behavioral’ goal for a student and to break that goal down into sub-tasks. (Each sub-task should be defined in such a way that it can be scored as ‘successfully accomplished’ or ‘not accomplished’.) • The constituent behaviors that make up the larger behavioral goal need not be directly related to each other. For example, ‘completed homework’ may include asA. sub-tasks ‘wrote indown homework Source: Kazdin, E. (1989). Behavior modification applied settings (4 ed.). Pacific assignment Gove, CA: Brooks/Cole.. th www.interventioncentral.org 102 Response to Intervention Discrete Categorization Example: Math Study Skills General Academic Goal: Improve Tina’s Math Study Skills The student Tina: Approached the teacher at the end of class for a copy of class note. Checked her daily math notes for completeness against a set of teacher notes in 5th period study hall. Reviewed her math notes in 5th period study hall. Started her math homework in 5th period study hall. Used a highlighter and ‘margin notes’ to mark questions or areas of confusion in her notes or on the daily assignment. Entered into her ‘homework log’ the amount of time spent that evening doing homework and noted any questions or areas of confusion. www.interventioncentral.org 103 Response to Intervention Discrete Categorization Example: Math Study Skills Academic Goal: Improve Tina’s Math Study Skills General measures of the success of this intervention include (1) rate of homework completion and (2) quiz & test grades. To measure treatment fidelity (Tina’s follow-through with sub-tasks of the checklist), the following strategies are used : Approached the teacher for copy of class notes. Teacher observation. Checked her daily math notes for completeness; reviewed math notes, started math homework in 5th period study hall. Student work products; random spot check by study hall supervisor. Used a highlighter and ‘margin notes’ to mark questions or areas of confusion in her notes or on the daily assignment. Review of notes by teacher during T/Th drop-in period. Entered into her ‘homework log’ the amount of time spent that evening doing homework and noted any questions or areas of confusion. Log reviewed by www.interventioncentral.org teacher during T/Th drop-in period. 104 Response to Intervention ‘Motivation Assessment in Advanced Subject Areas’ Activity Brief behavior analysis of motivation (e.g., Schoolwork Motivation Assessment) is most effective for basic skill areas. In your ‘elbow groups’: Discuss ways that RTI Teams could collect information about whether motivation is an ‘academic blocker’ on more advanced academic tasks (e.g., writing a term paper) or subject areas (e.g., trigonometry). www.interventioncentral.org 105 Response to Intervention RTI Teams: Recommendations for Data Collection www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention RTI Teams: Recommendations for Data Collection • Collect a standard set of background information on each student referred to the RTI Team. RTI Teams should develop a standard package of background (archival) information to be collected prior to the initial problemsolving meeting. For each referred student, a Team might elect to gather attendance data, office disciplinary referrals for the current year, and the most recent state assessment results. www.interventioncentral.org 107 Response to Intervention RTI Teams: Recommendations for Data Collection • For each area of concern, select at least two progress-monitoring measures. RTI Teams can place greater confidence in their progressmonitoring data when they select at least two measures to track any area of student concern (Gresham, 1983)-ideally from at least two different sources (e.g., Campbell & Fiske, 1959). With a minimum of two methods in place to monitor a student concern, each measure serves as a check on the other. If the results are in agreement, the Team has greater assurance that it can trust the data. If the measures do not agree with one another, however, the Team can investigate further to determine the reason(s) for the apparent discrepancy. www.interventioncentral.org 108 Response to Intervention RTI Teams: Recommendations for Data Collection • Monitor student progress frequently. Progress-monitoring data should reveal in weeks--not months-whether an intervention is working because no teacher wants to waste time implementing an intervention that is not successful. When progress monitoring is done frequently (e.g., weekly), the data can be charted to reveal more quickly whether the student’s current intervention plan is effective. Curriculum-based measurement, Daily Behavior Report Cards, and classroom observations of student behavior are several assessment methods that can be carried out frequently. www.interventioncentral.org 109 Response to Intervention Ideas to Empower Students to Take a Role in Their Own Intervention Plans Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Intervention Responsibilities: Examples at Teacher, School-Wide, and Student Levels Teacher Student • Signed agenda • ‘Attention’ prompts • Peer-Guided Pause • Take agenda to teacher to be reviewed and signed • Self-monitor and chart their organizational skills (e.g., bringing work materials to class) • Seeking help from teachers during free periods www.interventioncentral.org School-Wide • Lab services (math, reading, etc.) • Remedial course • Homework club • Providing additional instruction to students during selected free periods 111 Response to Intervention Unmotivated Students: What Works Motivation can be thought of as having two dimensions: 1. the student’s expectation of success on the task 2. ………………100 Multiplied by X the value that the student places ...………… 100 on achieving success on that learning task 0 The relationship between the two factors is multiplicative. If EITHER of these factors (the student’s expectation of success on the task OR the student’s valuing of that success) is zero, then the ‘motivation’ product will also be zero. Source: Sprick, R. S., Borgmeier, C., & Nolet, V. (2002). Prevention and management of behavior problems in secondary schools. In M. A. Shinn, H. M. Walker & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp.373-401). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. www.interventioncentral.org 112 Response to Intervention Intervention Plans for Secondary Students: The Motivational Component • Intervention plans for secondary students may require ‘motivational’ strategies to encourage engagement in learning www.interventioncentral.org 113 Response to Intervention Promoting Student Involvement in Secondary School RTI Intervention Team Meetings • Train students in self-advocacy skills to participate at intervention team meetings (can be informal: e.g., conversation with Guidance Counselor) • Provide the student with different options to communicate needs, e.g.,: – Learning needs questionnaire – Personal interview prior to meeting – Advocate at meeting to support student • Ensure student motivation to take part in the intervention plan (e.g., having student sign ‘Intervention Contract’) www.interventioncentral.org 114 Response to Intervention When Interventions Require Student Participation... • Write up a simple ‘Intervention Contract’ that spells out – What the student’s responsibilities are in the intervention plan – A listing of the educators connected to parts of the intervention plan that require student participation--and their responsibilities – A contact person whom the student can approach with questions about the contract • Have the student sign the Intervention Contract • Provide a copy of the Intervention Contract to the student and parents • Train the student to ensure that he or she is capable of carrying out all assigned steps or elements in the intervention plan www.interventioncentral.org 115 Response to Intervention Sample ‘Student Intervention Contract’ p. 16 www.interventioncentral.org 116 Response to Intervention If the Student Appears Unwilling to Follow Through With the Plan… 1. Verify that the student has the necessary skills to complete all steps or elements of the intervention plan without difficulty. Check that all adults who have a support role in the student’s personal intervention plan are carrying out their responsibilities consistently and correctly. Hold an ‘Exit’ conference with the student--either with the entire RTI Intervention Team or with the student’s ‘adult contact’. It is recommended that the student’s parent be at this meeting. At the ‘Exit’ meeting: 2. 3. 4. • • • • Review all elements of the plan with the student. Share the evidence with the student that he or she appears able to implement every part of the personal intervention plan. Tell the student that he or she is in control—and that the intervention cannot be successful unless the student decides to support it. Tell the student that his or her intervention case is ‘closed’ but that the student can restart the plan at any time by contacting the adult contact. www.interventioncentral.org 117 Response to Intervention Starting RTI in Your Secondary School: Enlisting students in intervention plans As a team: • Put together a set of strategies to train students to be self-advocates and to attend RTI Team meetings. • Discuss ways to motivate students to feel comfortable in accessing (and responsible FOR accessing) intervention resources in the school. www.interventioncentral.org 118 Response to Intervention Implementing Response to Intervention in Secondary Schools: Key Challenges to Changing a System Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Making RTI Work in Your Schools: Key Expectations www.interventioncentral.org 120 Response to Intervention Making RTI Work in Your Schools: Key Expectations • Teachers try a larger number of research-based classroom strategies before referring a student to the school’s Intervention Team. • Schools are able to find time and personnel coverage to schedule Intervention Team (IST) meetings. • The job descriptions of key people in a school change to match the needs of RTI (e.g., school psychologist, special education teacher). • The school recognizes that RTI is an ‘umbrella’ problem=solving approach that helps the district to address a range of important school issues such as low state test scores, deficient academic skills, absenteeism, and drop-outs. www.interventioncentral.org 121 Response to Intervention Making RTI Work in Your Schools: Key Expectations (Cont.) • Administrators show strong support for RTI, using their influence to encourage teacher follow-through with classroom interventions, helping to rework job descriptions to match RTI’s needs, etc. • RTI is accepted by the school community as a mainstream initiative, with the majority of representatives on the RTI Steering Group drawn from general education (e.g., Curriculum Director). • RTI is given the resources that it needs to grow, including funds for staff development and for the purchase of assessment services or products and intervention materials. • The district has a multi-year plan to implement RTI that builds the model at an ambitious but sustainable rate. www.interventioncentral.org 122 Response to Intervention Preventing Your School from Developing ‘RTI Antibodies’ • Schools can anticipate and take steps to address challenges to RTI implementation in schools • This proactive stance toward RTI adoption will reduce the probability that the ‘host’ school or district will reject RTI as a model www.interventioncentral.org 123 Response to Intervention Innovations in Education: Efficacy vs. Effectiveness “A useful distinction has recently emerged between efficacy and effectiveness (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001). Efficacy refers to intervention outcomes that are produced by researchers and program developers under ideal conditions of implementation (i.e., adequate resources, close supervision …). In contrast, effectiveness refers to demonstration(s) of socially valid outcomes under normal conditions of usage in the target setting(s) for which the intervention was developed. Demonstrations of effectiveness are far more difficult than demonstrations of efficacy. In fact, numerous promising interventions and approaches fail to bridge the gap between efficacy and effectiveness.” [Emphasis added] Source: Walker, H. M. (2004). Use of evidence-based interventions in schools: Where we've been, where we are, and where we need to go. School Psychology Review, 33, 398-407. p. 400 www.interventioncentral.org 124 Response to Intervention Role of ‘School Culture’ in the Acceptability of Interventions “…school staffs are interested in strategies that fit a group instructional and management template; intensive strategies required by at-risk and poorly motivated students are often viewed as cost ineffective. Treatments and interventions that do not address the primary mission of schooling are seen as a poor match to school priorities and are likely to be rejected. Thus, intervention and management approaches that are universal in nature and that involve a standard dosage that is easy to deliver (e.g., classwide social skills training) have a higher likelihood of making it into routine or standard school practice.” Source: Walker, H. M. (2004). Use of evidence-based interventions in schools: Where we've been, where we are, and where we need to go. School Psychology Review, 33, 398-407. pp. 400-401 www.interventioncentral.org 125 Response to Intervention Barriers in Schools to Innovations in Interventions “Factors that have been identified as barriers to … acceptance and implementation by educators [of effective behavioral interventions for at at-risk students] include characteristics of the host organization, practitioner behavior, costs, lack of program readiness, the absence of program champions and advocates within the host organization, philosophical objections, lack of fit between the program's key features and organizational routines and operations, and weak staff participation.” Source: Walker, H. M. (2004). Use of evidence-based interventions in schools: Where we've been, where we are, and where we need to go. School Psychology Review, 33, 398-407. p. 400 www.interventioncentral.org 126 Response to Intervention RTI: Research Questions Q: What Conditions Support the Successful Implementation of RTI? • • • • • RTI requires: Continuing professional development to give teachers the skills to implement RTI and educate new staff because of personnel turnover. Administrators who assert leadership under RTI, including setting staff expectations for RTI implementation, find the needed resources, and monitor the fidelity of implementation. Proactive hiring of teachers who support the principles of RTI and have the skills to put RTI into practice in the classroom. The changing of job roles of teachers and support staff (school psychologists, reading specialists, special educators, etc.) to support the RTI model. Input from teachers and support staff (‘bottom-up’) about how to make RTI work in the school or district, as well as guidance from administration (‘top-down’). Source: Fuchs, D., & Deshler, D. D. (2007). What we need to know about responsiveness to intervention (and shouldn’t be afraid to ask).. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(2),129–136. www.interventioncentral.org 127