BlackShackAlleyComparingNovelToFilm

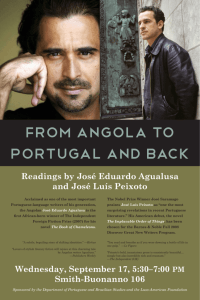

advertisement

Duncan Hussey Black France Midterm Essay 3/21/2012 Converting Novel to Film: Euzhan Palcy’s Adaptations to Black Shack Alley Euzhan Palcy’s standout work, Sugar Cane Alley (1983), is a film tightly based upon Joseph Zobel’s semi-autobiographical novel, Black Shack Alley. Set in Martinique in the early 1930’s, both the film and novel follow the life of the young protagonist, José, as he matures and struggles to escape the poverty and hardships of a sugar cane plantation in the colonial Caribbean. Aided by the sacrifice and love of his family, while both versions tell the same story of his eventual triumph, it is interesting to examine the subtle adaptations that Palcy made upon Zobel’s original text. Some of these changes, such as a stronger emphasis on José’s maturity and education in early scenes, are necessary to match the time scale of the book to that of the film. Others, such as character and dialogue changes, are artistic choices that highlight the close relationship between M’an Tine and José as well as directly confronting issues of racial inequality, slavery, and the push for a collective African heritage and identity. The end result is an outstanding film that maintains the authenticity and beauty of Zobel’s original novel while simultaneously challenging the viewer to think critically about the difficult racial issues present in colonial society. Perhaps the most obvious challenge associated with converting the novel Black Shack Alley to film is the inherent time discrepancy between the two media forms. In the original novel José matures over a period of many years, starting before the age of seven and finishing all the way through his secondary education at the lyceé on Fort de France. Such a length of time is impractical to portray with a single child actor, and therefore in order to create a reasonable timescale Palcy adapts the novel to make José appear more mature in early scenes. A particularly good example of this is the broken bowl incident, one of the very first plot elements present in both the film and novel. In the original text the incident occurs when José invites his friends inside to snack upon flour and the much desired sugar M’an Tine had left in the house. Spurred on by José’s own initiative, they then proceed to scour the entire shack for the sugar tin, in the process breaking M’an Tine’s bowl, which causes a young José to burst into tears (Zobel 17). In the novel the string of events serves as a testament to the youth and innocence of the children, however in the film Palcy portrays the incident in a different way. In her adaptation José is noticeably more respectful and protective of M’an Tine’s shack from the start, forcibly resisting his friends’ efforts to enter and even more strongly insisting that they call off their search for the sugar tin (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 4). Indeed, even when the bowl is broken, instead of bursting into tears José merely does his best to fix the pieces, acknowledging the punishment he will eventually face when M’an Tine returns. This difference may seem subtle, but it is necessary change in order for the story to seem plausible to the viewer. If José is to have the same physical appearance throughout the entire movie his maturity should also mimic it, and thus we see the change from the original version in the novel. Along the same lines, Palcy also noticeably altered the text in order to give José a strong educational background right from the start of the movie. A good example of this is the early presence of Carmen in the film, a character who normally isn’t introduced until late in the novel when José has already reached Fort de France. In doing so Palcy is able to immediately establish José as Carmen’s tutor despite his young age, providing the viewer with tangible evidence of José’s high intelligence and prior schooling (Sugar Cane Alley, minute . Even the décor of M’an Tine’s shack is altered in the film to convey this schooling, as the inside walls are covered with papers and advertisements that José must read aloud to M’an Tine before dinner (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 9:36) Just as with his increased maturity, this adaptation is necessary in order to justify José’s rapid rise through school at the PetitBourg all the way to Fort de France. It would be unrealistic to the viewer for José to begin and end his schooling all while having the same physical appearance, and thus these additions are elegant choices on Palcy’s part to help ease that transition. In addition to lessening the time discrepancies present in the film, Palcy also fortified the strength of the relationship between M’an Tine and José by deliberately removing his mother, Ms. Delia, from the story. Without Delia it is M’an Tine herself who must accompany José to Fort de France, and more importantly it is M’an Tine who works herself to exhaustion as a launderer in order to pay for José’s tuition at the lyceé. This simple change not only gives the viewer a concrete example of the depth of M’an Tine’s love and for José, and at a deeper level it makes her eventual death even more bittersweet. By directly linking M’an Tine’s physical labor to José’s education, Palcy allows the audience to view her eventual heart attack as a symbol of her ultimate sacrifice for José’s future and education. The devotion shows just how desperately M’an Tine wants José to escape the cane fields, providing a poignant example of the sad situation in which he and his friends were born. In addition to removing Ms. Delia, Palcy also added a new character, Leopold, whose sad experiences epitomize the racial divide in colonial Martinique. Potentially inspired by the character of Jojo in the novel, Leopold is the mulatto son of a wealthy béké, Mr. De Thoral, who befriends José halfway through the film. Their friendship, however, is forbidden by Thoral, who refuses to have his son play with black children (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 62). Even more tragically, later on his death bed he vows to leave his property to Leopold but refuses to officially recognize his son because of his race: “‘De Thoral is a name that has always belonged to whites for many generations… It is not a name that belongs to Mulattos’” (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 65). The scene, elegantly adapted to the new character Leopold, is actually taken directly from a story Carmen tells José in the original novel (Black Shack Alley). Overall I find the exchange particularly heartbreaking because it makes painfully clear the extent of racism present in Martinique at the time period. Even though Mr. de Thoral clearly cares for his son, the racial distinction between white and black is still so engrained in his mind that even his love can’t force him to part with his name. It’s a pitiful society when a father can’t even recognize his own son due to race, and thus the character of Leopold provides the audience with a depressing example of the extent of racism on Martinique. Leopold’s character also highlights the artificiality of racism later in the film when he is arrested and beaten for attempting to take a chicken from lands that belonged to his father. The scene is thought provoking because it introduces the potential of a physical struggle between the black workers and the béké, with the sugar cane workers brandishing their machetes in a riot only to be restrained by a chain fence and the gun of a mulatto servant (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 95) What I found so interesting was that the fear of physical harm, if only ever so briefly, seems to remove the power separation between white and black, leaving just equal men fighting for their different causes. The moment of mutual fear and equality is short lived, but even that glimpse personally served as a sharp reminder of how artificial the differences created by racism really are. As if to emphasize the sad inequality of the situation, a lone woman in the crowd begins to chant a song, “Martinique, tu souffres”, that describes the sad state of the French Caribbean colonies. Overall the scene serves as another example in which the Leopold’s character explicitly addresses issues of race, and therefore is a testament to the careful choices Palcy made in adapting the original novel to film. Finally, in addition to the racial issues confronted through Leopold, Palcy also alters the dialogue between characters to focus explicitly on the slave trade and the idea of a collective African heritage. The best example of these changes is found in the conversations between José and Mr. Medouze, the elderly story teller who shares José riddles and stories of his heritage. In the novel Medouze mentions Guinea as the birthplace of his family, however only in the film does he directly speak of the African slave trade and how the workers were brought to Martinique: “Everyday the old man spoke of his country… That country was called Africa. My Dad’s country. The country of your father’s father. The old black, sad and ugly, would always say to me ‘Medouze. Your old father will die soon, without ever understanding what happened when the whites landed here… The white men hunted us. They caught us with lassos. Then, after many days journey through the bush they took us to the edge of the big water. One day, we were unloaded here. We were sold to cut cane for the whites.’” (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 20) By adding this portion to the film Palcy explicitly confronts the slave trade, forcing the viewer to recognize just how recently it was prevalent in the Caribbean and other parts of the world. (Only three generations removed from José!) Furthermore the word choice employed by Medouze is particularly interesting, as Palcy deliberately replaces the specific country of Guinea with the continent of Africa as a whole, perhaps in conjunction with the pan-african movement emerging in the 70’s. Another example of this idea of a collective Africa can be found in José’s conversation with M’an Tine immediately following Medouze’s death: “‘M’an Tine. Mr. Medouze est en route pour l’Afrique’” (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 53). This quote is also not present in the original text, and once again references Africa as a whole rather than Guinea specifically. Indeed the film even ends with José commenting that M’an Tine “is departing for the Africa of Mr. Medouze” (Sugar Cane Alley, minute 138), another reinforcement of a collective African home and identity. Overall these adaptations add another level of complexity to the film and therefore are just another example of Palcy’s careful thought and ingenuity. In conclusion, Euzhan Palcy’s adaptation of Joséph Zobel’s novel Black Shack Alley elegantly handles the technical issues of converting the book to film while also directly confronting racial issues in colonial society. By maintaining the structural backbone she pays homage to the authenticity and beauty of Zobel’s original text whilst her additions cause the viewer to think critically about the difficult racial issues associated with slavery and colonial society. On the whole it is an outstanding film taken from an excellent story, and fully deserved the critical praise and attention it received.