We value collaboration.

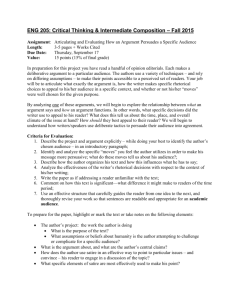

advertisement

Rhetoric refers to the study, uses, and effects of spoken, written, and visual language. Department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies Current and Emerging Values of the Lower Division Writing Program: Rhetoric Collaboration Technology We are a program. • • We deliver goals and instruction consistently across multiple sections. We value instructors’ innovative instances of our goals and assignments. We communicate as a program. • We use Blackboard to present course materials and communicate with our students. We communicate as a program. • We use Blackboard to communicate with our program. Our program consists of two courses. • RWS 100 and 101: The Rhetoric of Written Argument Our program consists of two courses. • RWS 200: The Rhetoric of Written Argument in Context We know what we teach—the actions listed in our learning outcomes. In RWS 100, students: 1. construct an account of an author’s project and argument; translate an argument into their own words; 2. construct an account of an author’s project and argument and carry out small, focused research tasks to find information that helps clarify, illustrate, extend or complicate that argument; use appropriate reference materials, including a dictionary, in order to clarify their understanding of an argument; 3. 4. construct an account of two authors’ projects and arguments and explain rhetorical strategies that these authors— and by extension other writers—use to engage readers in thinking about their arguments; construct an account of two author’s projects and arguments in order to use concepts from one argument as a framework for understanding and writing about another. In RWS 200, students: 1. construct an account of an argument and identify elements of context embedded in it, the clues that show what the argument is responding to--both in the sense of what has come before it and in the sense that it is written for an audience in a particular time and place; examine a writer’s language in relation to audience, context and community; 2. follow avenues of investigation that are opened by noticing elements of context; research those elements and show how one's understanding of the argument is developed, changed, or evolved by looking into its context; 3. given the common concerns of two or more arguments, discuss how the claims of these arguments modify, complicate or qualify one another; 4. consider their contemporary, current life as the context within which they are reading the arguments assigned in the class; position themselves in relation to these arguments and additional ones they have researched in order to make an argument; draw on available key terms, concepts or frameworks of analysis to help shape the argument. Building on RWS 100, 200 introduces the concept of Context. Context: The larger textual and cultural environment in which specific rhetorical acts take place Example text: MLK Jr. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” Context: References to a particular audience Responding to a statement by eight Alabama clergymen. Context: References to past conversations about nonviolent protest - Socrates and Ghandi Context: References to current writing environment – author’s location in jail as a result of involvement with lunch counter sit-ins We encourage innovative implementations of these outcomes. RWS 200 Words and Images Sequence, Spring 2006 Paper 1: Articulating an Argument and What It Reveals About Its Context For this project: Conduct a survey of friends, family, and classmates to learn about assumptions you (and people like you) have about photography—we will work on this part as a separate class assignment. Construct for an audience that has not read John Berger’s essay, “Appearances,” an account of his project and argument. You should provide a sense of what the issues are for him, the assumptions that he comes to reject, and how he looks at photographs that matter to him. Identify for your reader some clues about the context in which the piece was written—things that show it was written in a particular time and place that is somewhat distant from us. Finally, assign significance to the piece by suggesting, in light of the survey that you conducted, why Berger should be read at this point in time, in our own context. We encourage innovative implementations of these outcomes. RWS 200 Rereading America Sequence, Spring 2006 Paper 1: Articulating an Argument and What It Reveals About Its Context Project # 1 consists of a written paper and a power point presentation, using one of the texts from our course readings (Barber, Steinhorn & Brown, Medved, Gitlin, Wynter). Construct for an audience that has not read the text an account of the author’s project and argument. Provide information for one of the following context categories: the author’s life and works, the context of publication, the larger conversation, and the author’s purpose (political goals). Using the information from the written paper, each group member makes two PowerPoint slides: one that presents the information and one that provides an explanation of how his/her particular area of context affects the reader’s understanding of the overall text. We articulate the goals for each: • Class Session • Assignment • Writing Prompt We talk about professional and student writing in the same way—rhetorically. • We talk about what sentences, paragraphs, images, and texts do for readers. Showing that this claim really is in the text, and why E. makes it. An important part of Ehrenreich’s argument is that the poor are invisible to affluent people. She suggests that the affluent “are less and less likely to share public spaces and services with the poor,” that political parties are unwilling to “acknowledge that low-wage work doesn’t lift people out of poverty” (217) and that media attention focuses more on “occasional success stories” than on the rising numbers of poor and hungry people (218). The fact that the poor are invisible contributes to the lack of attention that the problem of low wages is getting. Writer telling reader one piece of E.’s argument, one claim. Explaining why the “invisibility claim” is significant We value criteria-based evaluation of papers. • We distribute criteria for evaluation together with each prompt. RWS 100 Economics and Justice Sequence, Fall 2005 Project #4 James C. Scott’s “Behind the Official Story” makes an argument about how to research and analyze relations of power. His text provides an opportunity to explore Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed as a research project. Looking at Ehrenreich through Scott’s terminology, make an argument about her perspective on economic power relations. Successful papers will: 1. Introduce the project of examining Ehrenreich through Scott 2. Give a reader unfamiliar with the text a thumbnail sketch of Scott’s argument 3. Give a reader unfamiliar with the text a thumbnail sketch of Ehrenreich’s research project 4. Discuss specific passages in Ehrenreich by using terminology from Scott 5. Make an argument about Ehrenreich as a book concerned with economic power relations 6. Manage quotations well, effectively commenting on what the quoted material is doing (reporting, interpreting, analyzing, etc.) and what readers ought to notice in it. 7. Conclude by showing the significance of this work for us as citizens and as writers. We value criteria-based evaluation of papers. • We use these criteria to comment on papers and show students how we arrive at their grades. Introduce the project of examining Ehrenreich through Scott You have done a wonderful job of articulating your project—looking at Ehrenreich’s book through Scott’s terminology. I’m especially impressed by your sentence announcing that Ehrenreich’s work illustrates Scott’s argument for a new type of social science. Give a reader unfamiliar with the text a thumbnail sketch of Scott’s argument The paragraph in which you do this weaves together a quick series of quotations from Scott. You’ve selected key passages—the ones in which Scott defines terms—but I’d like to see an account in your own words of Scott’s argument. You’re almost there, since you’ve zeroed in on the places where he gives us key concepts. Give a reader unfamiliar with the text a thumbnail sketch of Ehrenreich’s research project I’d say that you did this better in the first paper of the semester. Why not use some of that strong material here, and make sure that a reader can tell exactly what Ehrenreich sets out to do in her research? I think this will only take a couple more sentences. When you add that material, you’ll then have a very long opening paragraph, and you’ll need to decide whether to devote a separate paragraph to describing Ehrenreich’s project. We value collaboration. • Collaborative Teaching Innovations in the program have come out of collaborative teaching. We value collaboration. • Collaborative Writing RWS 200 Rereading America Sequence, Fall 2005 Paper 4: Making an argument in relation to ongoing research and discussion. Using the readings by D’Souza, Hertsgaard, Mosley, and Williams from Rereading America as the contextual framework, each group will write one formal paper approximately 6 pages long that argues a position or positions regarding America’s role in the world. We show students how to be apprentices to the kinds of writing they’re reading in the class. Published Author Mary Kaldor: In this essay, I shall distinguish between the different types of armed forces that are emerging in the post-Cold War world . . . and discuss how they are loosely associated with different modes of state transformation and different forms of warfare . . . . The point is to provide a schematic account of what is happening in the field of warfare . . . . I shall suggest that the emphasis that has been increasingly accorded to international law, particularly humanitarian law, offers a possible way forward. (270) RWS Learning Outcome: Use metadiscourse to signal the project of a paper and guide a reader from one idea to the next. We show students how to be apprentices to the kinds of writing they’re reading in the class. SDSU Student Tyler Stevens: In this paper I will assess O’Brien’s story and Kaldor’s speech, and show how war inevitably affects many more people besides the soldiers that are fighting in it. I will also point out each author’s rhetorical strategies, hoping to distinguish which author is more effective in their argument, and what moral uncertainties are dislodged in their writings. (1) RWS Learning Outcome: Use metadiscourse to signal the project of a paper and guide a reader from one idea to the next. We give students opportunities to reflect on their growth in writing and reading in relation to our learning outcomes. Review and reflect on the four papers you wrote this semester. What are two ways you feel your writing has strengthened? Give specific examples from your papers to illustrate this. How do these strengths add to the overall success of your writing? Discuss how these strengths increased your ability to accomplish one of our chief course outcomes: Construct an account of an argument; translate that argument into your own words. -RWS 100 Final In-Class Writing We teach what we assess. We assess what we teach. • We therefore use classroom activities and homework assignments that lead into or model the work students will be doing in their papers. RWS 100 Project #2, Preparatory Homework The upcoming paper on Schlosser’s text will involve: 1) constructing an account of Schlosser’s argument and 2) explaining how outside sources deepen and clarify your understanding of his argument. Below are a number of articles to locate, read, and consider incorporating into your upcoming writing assignment. For homework: • Go to the campus Library online, click on “article databases,” then EBSCO, and locate Julia Galeota’s essay “Cultural Imperialism: An American Tradition,” Foreign Policy’s interview with Jack Greenberg, entitled “McAtlas Shrugged,” Mohamed Zayani’s Book Review of The McDonaldization of Society, and “Big Mac’s Makeover,” published in the Economist. • Select a passage from one of these outside links and, in a brief paragraph, explain how it enriches your understanding of Schlosser’s argument. -Amy Allen and Micah Jendian We teach the processes of drafting and revising, using feedback from instructors and peers. • We make peer review a focused process, grounded in written criteria for evaluation. Peer Review Worksheet for Project #1: Argument Analysis Editor’s Name: _________________ Writer’s Name:__________________ Instructions: Please do your best to give helpful, specific feedback to the writers whose papers you review. 1. What is the writer’s project or argument? If you think the writer does not have a project yet, what project might be suggested by the draft you’ve read? 2. Does the writer adequately summarize Ehrenreich’s project? Below, list elements of her project that were overlooked. 3. Does the writer identify one chapter of the book to analyze? Which chapter? Does the writer demonstrate how the chapter supports Eherenreich’s project? 4. Go through your partner’s paper and mark with a star all the places where you feel the writer is interpreting and thinking rather than merely summarizing. Also, mark places with a large “S” where you feel the writer is providing unnecessary summary that does not contribute to the argument of the paper. -Carrie Preston We are moving toward teaching: • Visual rhetorics In the following image, a sample of her work, Barbara Kruger demonstrates combining an image with words to provoke the audience into thinking about gender and identity. Although to some people, this image is quite obvious, to others, it may be less clear; nevertheless it is an image created for the audience to interpret. . . . -RWS 200 student Jessica Marsh We are moving toward teaching: • The rhetoric of technology Video created by SDSU student Mike … for project #4 in Nancy Fox’s fall 2005 Words and Images sequence. Course texts focused on documentary analysis. We welcome technological innovations that enhance teaching practices. Liane Bryson recording audio feedback on a student’s paper. We have a Lower Division Writing Committee Made up of: • Two graduate students • Two lecturers • A Program Director The Committee: We have a Lower Division Writing Committee Made up of: • Two graduate students • Two lecturers • A Program Director The Committee: • Has a rotating faculty membership • Collaborates with faculty to develop and revise curriculum • Invites faculty to share their innovations and suggest curricular revision. • Responds to all pedagogical, curricular and administrative questions about RWS 100/200. We assess how we’re doing as a program. Fall 2005 Assessment Project 25 DRWS Instructors taught Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed. For our assessment project, 10 Instructors contributed student papers analyzing Ehrenreich’s argument Eight instructors read 61 papers, using a three-tiered rubric: Strong, Moderate, Low 30 Value to Instructors: • discussing student work across sections • seeing how our students did with a complex assignment 25 20 15 10 5 0 Low Moderate Strong We value student writing. We value student writing. We value student writing. We value student writing. We see students as writers. Suzanne Aurilio asks Liane Bryson’s RWS 200 students to comment on a project that involved visual literacy. This presentation has been brought to you by the current Lower Division Writing Committee Peter Manley, Ellen Quandahl, Liane Bryson, Jesse Roach, Heather Pistone With thanks to our colleagues and students in the Lower Division Writing Program.