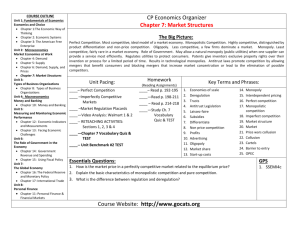

Chapter 10 - Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

advertisement

Monopolistic Competition And Oligopoly • On any given day, you are probably exposed to hundreds of advertisements • In perfect competition and monopoly firms do little, if any, advertising • Where, then, is all the advertising coming from? Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 1 The Concept of Imperfect Competition • Refers to market structures between perfect competition and monopoly • Types of imperfectly competitive markets – Monopolistic competition – Oligopoly Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 2 Monopolistic Competition • Hybrid of perfect competition and monopoly, sharing some of features of each – A monopolistically competitive market has three fundamental characteristics • Many buyers and sellers • Sellers offer a differentiated product • Sellers can easily enter or exit the market Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 3 Many Buyers and Sellers • Under monopolistic competition, an individual buyer is unable to influence price he pays • But an individual seller, in spite of having many competitors, decides what price to charge Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 4 Sellers Offer a Differentiated Product • Each seller produces a somewhat different product from the others • Faces a downward-sloping demand curve – In this sense is more like a monopolist than a perfect competitor – When it raises its price a modest amount, quantity demanded will decline (but not all the way to zero) Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 5 Sellers Offer a Differentiated Product • What makes a product differentiated? • Product differentiation is a subjective matter • Thus, whenever a firm (that is not a monopoly) faces a downward-sloping demand curve, we know buyers perceive its product as differentiated Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 6 Easy Entry and Exit • Same as in perfect competition – Ensures firms earn zero economic profit in long-run • In monopolistic competition, however, assumption about easy entry goes further – No barrier stops any firm from copying the successful business of other firms Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 7 Monopolistic Competition in the Short-Run • Individual monopolistic competitor behaves very much like a monopoly • Key difference is this – When a monopolistic competitor raises its price, its customers have one additional option – to buy from another seller Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 8 Figure 1: A Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Short Run Dollars $70 1. Kafka services 250 homes per month, where MC and MR intersect . . . A ATC 2. and charges $70 per home. d1 30 MR1 3. ATC at 250 units is less than price, so profit per unit is positive. 4. Kafka's monthly profit–$10,000–is the area of the shaded rectangle. 250 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles MC Homes Serviced per Month 9 The Long-Run • No barriers to entry and exit—the firm will not enjoy its profit for long • Under monopolistic competition, firms can earn positive or negative economic profit in short-run • But in long-run, free entry and exit will ensure that each firm earns zero economic profit just as under perfect competition Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 10 Figure 2: A Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Long Run In the long run, profit attracts entry, which shifts the firm's demand curve leftward. Dollars MC ATC $40 E The typical firm produces where its new MR crosses MC. MR2 100 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Entry continues until P = ATC at the best output level, and economic profit is zero. d1 d2 250 MR1 Homes Serviced per Month 11 Excess Capacity Under Monopolistic Competition • In long-run, a monopolistic competitor will operate with excess capacity • Excess capacity suggests that monopolistic competition is costly to consumers • Does that mean consumers prefer perfect competition to monopolistic competition? Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 12 Nonprice Competition • Any action a firm takes to increase demand for its output—other than cutting its price—is called nonprice competition • Nonprice competition is another reason why monopolistic competitors earn zero economic profit in long-run • All this nonprice competition is costly Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 13 Oligopoly • An oligopoly is a market dominated by a small number of strategically interdependent firms • In such a market, each firm recognizes its strategic interdependence with others Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 14 Number of Firms • Oligopoly requires that a few firms dominate the market • No absolute number at which oligopoly ends and monopolistic competition begins Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 15 Market Domination • Strategic interdependence requires that a few firms dominate the market • As combined market share shrinks, strategic interdependence becomes weaker • Oligopoly is a matter of degree – Not an absolute classification Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 16 Economies of Scale: Natural Oligopolies • When minimum efficient scale (MES) for a typical firm is a relatively large percentage of market – A large firm will have lower cost per unit than a small firm • Does it remind you of monopoly? How is this different? Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 17 Barriers to entry • Reputation - A new entrant may suffer just from being new • Strategic barriers - Oligopoly firms often pursue strategies designed to keep out potential competitors • Legal barriers - Patents and copyrights, Govt. legislation Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 18 Oligopoly vs. Other Market Structures • Oligopoly presents the greatest challenge to economists • Essence of oligopoly is strategic interdependence • Need new tools of modeling • One approach—game theory—has yielded rich insights into oligopoly behavior Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 19 The Game Theory Approach • Game theory • In all games, except those of pure chance, a player’s strategy must take account of the strategies followed by other players • Game theory analyzes oligopoly decisions as if they were games Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 20 The Prisoner’s Dilemma • Each of four boxes in payoff matrix represents one of four possible strategy combinations that might be selected in this game – Upper left box: Both Rose and Colin confess – Lower left box: Colin confesses and Rose doesn’t – Upper right box: Rose confesses and Colin doesn’t – Lower right box: Neither Rose nor Colin confesses Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 21 Figure 3: The Prisoner’s Dilemma Colin’s Actions Confess Don’t Confess Colin gets 20 years Confess Rose gets 20 years Colin gets 30 years Rose gets 20 years Rose’s Actions Colin gets 3 years Don’t Confess Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Rose gets 20 years Colin gets 5 years Rose gets 20 years 22 The Prisoner’s Dilemma • Regardless of Rose’s strategy Colin’s best choice is to confess • “Confess” is the dominant strategy for both • Outcome of this game is an example of a Nash equilibrium • As long as each player acts in an entirely self-interested manner Nash equilibrium is best outcome for both of them Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 23 Simple Oligopoly Games • To apply the same method to a simple oligopoly market • Duopoly - Oligopoly market with only two sellers • Assume that Gus and Filip must make their decisions independently • No matter what Filip does, Gus’s best move is to charge a low price—his dominant strategy • The same holds for Filip • The outcome is a Nash equilibrium Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 24 Figure 4: A Duopoly Game Gus’s Actions Confess Don’t Confess Gus’s profit = $25,000 Confess Filip’s Actions Don’t Confess Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Filip’s Profit = $25,000 Gus’s profit = $75,000 Filip’s Profit = $–10,000 Gus’s profit = –$10,000 Filip’s Profit = $75,000 Gus’s profit = $50,000 Filip’s Profit = $50,000 25 Oligopoly Games in the Real World • Will typically be more than two strategies from which to choose • Will usually be more than two players • In some games, one or more players may not have a dominant strategy – A game with two players will have a Nash equilibrium as long as at least one player has a dominant strategy – When neither player has a dominant strategy, we need a more sophisticated analysis to predict an outcome to the game Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 26 Oligopoly Games in the Real World • We’ve limited the players to one play of the game – In reality, for gas stations and almost all other oligopolies, there is repeated play • Where both players select a strategy • Observe the outcome of the trial • Play the game again and again, as long as they remain rivals • One possible result of repeated trials is cooperative behavior Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 27 Cooperative Behavior in Oligopoly • In real world, oligopolists will usually get more than one chance to choose their prices • The equilibrium in a game with repeated plays may be very different from equilibrium in a game played only once Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 28 Explicit Collusion • Simplest form of cooperation is explicit collusion • Most extreme form of explicit collusion is creation of a cartel • If explicit collusion to raise prices is such a good thing for oligopolists, why don’t they all do it? • But oligopolists can collude in other, implicit ways Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 29 Tacit Collusion • Any time firms cooperate without an explicit agreement, they are engaging in tacit collusion • Tit for tat – A game-theoretic strategy of doing to another player this period what he has done to you in previous period • However, gentle reminder of tit-for-tat is not always effective in maintaining tacit collusion Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 30 Tacit Collusion • Another form of tacit collusion is price leadership • With price leadership, there is no formal agreement Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 31 The Limits to Collusion • Oligopoly power—even with collusion— has its limits – Even colluding firms are constrained by market demand curve – Collusion—even when it is tacit—may be illegal – Collusion is limited by powerful incentives to cheat on any agreement Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 32 The Incentive to Cheat • Go back to Gus and Filip for a moment – One way or another they arrive at high-price cooperative solution – Will the market stay there? • Each player has an incentive to cheat • Analyzing this sort of behavior requires some rather sophisticated game theory models Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 33 When is Cheating Likely? • Cheating is most likely to occur—and collusion will be least successful—under the following conditions – Difficulty observing other firms’ prices – Unstable market demand – Large number of sellers Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 34 Figure 5a: Advertising in Monopolistic Competition 1.Before advertising, long-run economic profit is zero. Dollars $120 3. But in the long run, imitation and entry bring economic profit back to zero. B C 100 ATCads ATCno ads A 60 4. Advertising can lead to a higher price in the long run, as in this panel . . . 2. In the short run, the first firms to advertise earn economic profit. dads dno ads 1,000 2,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles dall advertise 6,000 Bottles of Perfume per Month 35 Figure 5b: Advertising in Monopolistic Competition Dollars $120 5. or to a lower price B in the long run, as in this panel. dall advertise A 60 50 C ATCads ATCno ads dads dno ads 1,000 2,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 6,000 Bottles of Perfume per Month 36 Using the Theory: Advertising in Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly • Perfect competitors never advertise and monopolies advertise relatively little – But advertising is almost always found under monopolistic competition and very often in oligopoly • Why? – All monopolistic competitors, and many oligopolists, produce differentiated products • Since other firms will take advantage of opportunity to advertise, any firm that doesn’t advertise will be lost in shuffle Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 37 Advertising and Collusion in Oligopoly • Oligopolists have a strong incentive to engage in tacit collusion • Take airline industry as an example • In theory, any airline should be able to claim superior safety – Yet no airline has ever run an advertisement with information about its security policies or attacked those of a competitor Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 38 Figure 6: An Advertising Game American's Actions Run Safety Ads Don't Run Ads Run Safety Ads United's Actions Don't Run Ads Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles American earns low profit United earns low profit American earns high profit United earns very low profit American earns very low profit United earns high profit American earns medium United profit earns medium profit 39 The Four Market Structures: A Postscript • Different market structures – Perfect competition – Monopoly – Monopolistic competition – Oligopoly • Market structure models help us organize and understand apparent chaos of realworld markets Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 40