What is the future for golf to make it sustainability? Keep it green

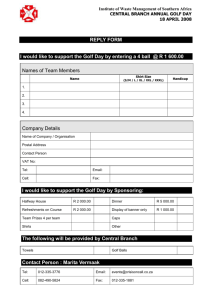

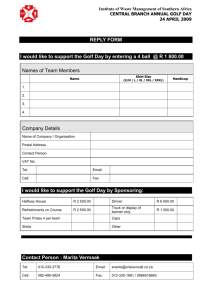

advertisement