Lesson 1-Crime and Justice

advertisement

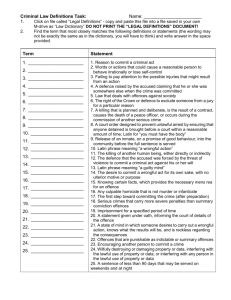

Intro to Criminal Law? Expectations Explain the purpose of criminal law Explain the legal definition of a crime and the concepts of mens rea, actus reus, and strict and absolute liability Analyze theories about criminal conduct and the nature of criminal behaviour, and explain what constitutes a crime in Canadian law Crime: Canadian Definition a violation of a law that prohibits specific activities, and for which there is a punishment that is set out by the state In Canada, a crime is anything that is defined by Parliament to be a crime. Only offences defined in federal law can truly be called crimes in Canada Activities covered by provincial or municipal laws for which there are penalties similar to those for criminal acts, are not “crimes” per se, but are generally referred to simply as “offences” or “Quasi-Criminal Law”. i.e., speeding, not wearing a seatbelt, drinking under age To be convicted of a crime… …two elements are required Mens Rea + Actus Reus = A Crime A defendant must not only commit a guilty act, he must also have the intention to commit a guilty act and thus have a guilty mind. Actus Reus (Guilty Act) In any offence, the actus reus can refer either to a specific action, or to the failure to act. For example, the failure to do something that is considered to be one’s duty, such a parent’s duty “to provide the necessaries of life to a child under the age of sixteen years” (215), can be considered a wrongful act under the Criminal Code. Actus Reus (Guilty Act) The actus reus of a criminal act must be voluntary. Actions over which an accused has no control are not actions which will normally result in criminal liability. Example: A person who has a heart attack at the wheel of a car and drives into another vehicle has not voluntarily committed the actus reus of the offence of dangerous driving. Mens Rea (Guilty Mind) The Crown must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant carried out a guilty act with the criminal intent or mens rea. Intent in the legal sense means having knowledge or being reckless or wilfully blind to the consequences of an act. Depending on the crime, the definition of intent can change General Intent versus Specific Intent • General intent • Means to commit a wrongful act for its own sake, with no other purpose or motive • Dave punches Luke because he is angry. Dave has general intent to commit assault. • For mens rea to be proven, all that needs to be done is to show that Dave punched Luke General Intent versus Specific Intent • Specific intent • Involves intent in addition to the general intent to commit the crime. It is committing one wrongful act to accomplish another • E.g Burglary is the breaking and entering of a dwelling-house with intent to commit an indictable offense. The break and enter requires general intent, the intent to commit an indictable offense requires specific intent • In order to prove burglary, the Crown not only has to show that a person broke into a house, but also had the specific intent of stealing. INTENT vs. MOTIVE • While intent refers to the state of mind with which an act is done or not done • Motive is what prompts a person to commit an act or not act • If a person kills her mother to receive an inheritance, the inheritance is motive. This does not establish state of mind to commit murder • Crown must prove intent by showing killing was planned and deliberate Knowledge • In order to have the requisite mens rea to commit a crime, a person must have some knowledge of the actus reus of the crime • Eg. S 268 1 (a) of the Criminal Code states that “Everyone who, knowing that a document is forged, uses, deals, or acts upon it” is guilty of circulating a forged document • To establish guilt, the Crown only has to prove that the person knew the document was forged.... Nothing about intent. Recklessness & Negligence Crown can also establish mens rea by proving accused acted reckless or negligent. • Recklessness • Usually involves taking an unjustifiable risk that a reasonable person would not take • Eg. recklessly shooting a pellet gun into a crowd. The accused may not have tried to hurt someone, but they should have been able to foresee harm • Negligence • doing something or omitting to do something with “wanton disregard for the lives or safety of other persons” Example: throwing a beer bottle out of a moving vehicle and injuring someone Willful Blindness • Suspects a criminal outcome but does not ask the questions to confirm turning a blind eye to the consequences of your action Example: buying stolen property that you should know has been stolen • Eg. transporting something illegal such as drugs in a trunk Sleepwalking a Murder Defense? Kenneth Parks, a 23-year-old Toronto man with a wife and infant daughter, was suffering from severe insomnia caused by joblessness and gambling debts. Early in the morning of May 23, 1987 he arose, got in his car and drove 23 kilometers to his in-laws' home. He stabbed to death his mother-in-law, whom he loved and who had once referred to him as "a gentle giant." Parks also assaulted his father in law, who survived the attack. He then drove to the police and said "I think I have killed some people . . . my hands," only then realizing he had severely cut his own hands. Under police arrest he was taken to the hospital where he underwent repair of several flexor tendons of both hands. Is Parks Guilty or Not Guilty? NOT Guilty Because he could not remember anything about the murder and assault, had no motive for the crime whatsoever, and did have a history of sleepwalking, his team of defense experts (psychiatrists, a psychologist, a neurologist and a sleep specialist) concluded Ken Parks was 'asleep' when he committed the crime, and therefore unaware of his actions. Parks' sleepwalking defense proved successful and on May 25, 1988, the jury rendered a verdict of not guilty. Subsequently Parks was also acquitted of the attempted murder of his father-in-law. The government appealed the decision and in 1992 the Canadian Supreme Court upheld the acquittals (R v. Parks, August 27, 1992). Types of Offences The nature of the offence determines which court has jurisdiction to hear the case, the powers of police to arrest, the accused’s right to be released before trial, and the kind of trial the accused receives. Three Types of Offences Summary Conviction Offences Indictable Offences Hybrid Offences Summary Conviction These offences are the least serious and trials for these convictions are held at the lower courts of the Ontario Court of Justice. The accused does not have a right to a jury trial. Trials in these cases are held in front of a judge alone, and sentencing for this type of offence ranges, with the maximum penalty being a fine of up to $2000 and/or six months in jail, unless otherwise specified by law. Summary Conviction Cont… Usually a person is not arrested for a summary offence, but will receive a notice to appear in court. The accused does not have to appear in court personally. A lawyer may represent the person in the court proceedings. A person cannot be fingerprinted for a summary conviction offence and is eligible for a pardon three years after the sentence is completed. Examples of summary offences include: causing a public disturbance, loitering, and having open alcohol in public. Indictable Offences Indictable offences are more serious than summary offences The procedure followed depends on the seriousness of the offence. For less serious indictable offences, trials are done before a provincial court judge, while the most serious indictable offences, such as murder, must be tried by a judge and jury. For some indictable offences, the accused is put to an election between being tried by a provincial court judge, a superior court judge alone, or a superior court judge with a jury. Indictable Offence Cont… A person charged with an indictable offence must show up personally in court. There is no limit on how much time can elapse between the alleged act and the arrest, which means that police can charge the person years after the offence occurred. The maximum penalty for indictable offences is life imprisonment. Examples of indictable offences include: murder, robbery, and kidnapping. Hybrid Offences Hybrid offences are also known as “dual procedure offences” and can be tried as either summary conviction or indictable offences. The Crown chooses whether it wants to prosecute as a summary or an indictable offence, usually depending upon the circumstances of the incident, and factors about the offender. Hybrid Offences Con’t… Examples of hybrid offences include: impaired driving, assault, theft under $5000, and failing to provide the necessaries of life. Most offences in the Criminal Code are hybrid offences. Hybrid offences are treated as indictable offences until the Crown chooses which way it wants to proceed. This means that an accused will be fingerprinted on arrest, even though it is possible that he will be tried for a summary conviction offence. Incomplete Crimes Incomplete crimes are generally considered to be crimes where the actus reus element has not been completed. Note: Attempted crimes are NOT considered incomplete crimes! The mere fact that an attempt fails does not mean the crime lacks actus reus. Incomplete crimes generally include: • conspiracy • aiding • abetting • accessory After the fact • Party to common Intention • Counselling Sidebar Criminal Attempts 24. (1) Every one who, having an intent to commit an offence, does or omits to do anything for the purpose of carrying out the intention is guilty of an attempt to commit the offence whether or not it was possible under the circumstances to commit the offence. Question: How far does one have to go to be charged with an “attempted” offence? Preparation is not enough to constitute an attempt. 24. (2) The question whether an act or omission by a person who has an intent to commit an offence is or is not mere preparation to commit the offence, and too remote to constitute an attempt to commit the offence, is a question of law. Conspiracy Conspiracy: An agreement between two or more persons to commit a criminal act. Those forming the conspiracy are called conspirators. Party to Common Intention Shared responsibility among criminals for any additional offences that are committed in the course of the crime they originally intended to commit. Aid / Abet Aid: Help commit a crime. To assist by way of an action that, in of itself, is not a crime. (ie. Looking out for police.) Standing on a corner looking at cars coming down the road is not a criminal act, but the mental intent in this circumstance constitutes a criminal offence. Abet: The act of encouraging or inciting another to do a certain thing, such as a crime. The act itself may not be criminal (ie. shouting at someone), but the mental intent (ie. encouraging someone to commit a crime) is criminal. Accessory After the fact: 23. (1) An accessory after the fact to an offence is one who, knowing that a person has been a party to the offence, receives, comforts or assists that person for the purpose of enabling that person to escape. Repealed: No married person whose spouse has been a party to an offence is an accessory after the fact to that offence by receiving, comforting or assisting the spouse for the purpose of enabling that person to escape. Counselling • A crime that involves advising, recommending or persuading another person to commit a criminal offence.