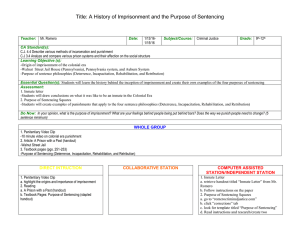

Punishment

Punishment

Rationale

Social contract

– Avoid chaos by giving State authority to punish us for our transgressions – within limits

Goals

– Retribution

– Reform

–

–

Incapacitation

Deterrence

– Rehabilitation

Issues

– Can punishment and treatment coexist?

–

–

Why are some offenses punished more severely than others?

Are the poor unfairly treated?

More likely to be selected?

More severely punished?

Are white-collar criminals more leniently punished?

Martha Stewart

– In 2001, after a phone call by her stockbroker, who got an illegal insider tip, she sold 4,000 shares of a stock just before a negative report about the company.

– In 2004 Stewart was convicted by a jury of conspiracy, obstruction and lying to investigators. She could have received 20 years. She received ten months and served five in prison and five at home. She also paid

$195,000 to settle SEC fraud charges.

Jeffrey Skilling

–

–

–

–

In 2006 the former Enron president received 24 years for a massive accounting fraud that grossly overvalued the company, making major stockholders like himself and other top Enron executives incredibly rich.

Enron’s collapse led to investor losses of $60 billion. All employees lost their jobs and pensions.

Ken Lay, the company’s chairman president, was also convicted. He died from a heart attack several months later. His conviction, on appeal, was overturned.

Former CFO Andrew Fastow, who cooperated with the government, got six years.

Purpose: retribution

Not meant to deter or prevent crime

Sets boundaries for behavior

Replaces vengeance and vigilantism with justice

Expresses social disapproval

Binds society

Provides opportunity for personal “salvation”

Punish crime or the criminal?

– Determinate: according to the crime

– Indeterminate: according to the criminal

Justice v. “deserts” models of punishment

–

–

Justice – punishment as a social response to crime

Deserts – punishment as a proportional response to misbehavior

Purpose: prevention

Deterrence

– Focus on needs of society – not individuals

–

–

General deterrence: discourage persons in general from committing an offense

–

–

Specific deterrence: discourage individuals from committing an offense

Assumes that people are rational

Incapacitation

– that criminals make cost/benefit analysis

Prevent crime by removing offenders from society

–

–

Length of incapacitation varies according to various factors

Perceived seriousness of offense

Likelihood of recidivating

Extremes

Mandatory sentences

Three-strikes laws

Death penalty

Treatment

–

Can crime be “cured”?

–

–

Should treatment be available?

Should participation be mandatory?

Goal: utility or equity?

Prevention -v- retribution

– Prevention emphasizes utility

– Retribution emphasizes fairness

– Move to determinate sentencing

Von Hirsch and Hanrahan – “modified just deserts”

–

–

Desert justifies a range of punishment for each kind of offense

Penalties can be adjusted for their preventive value based on individual differences

Prediction

Both rationales of punishment – prevention and retribution (deserts) require predicting future conduct

– Is it possible to predict dangerousness or recidivism?

Errors in prediction

–

–

Type I: Wrongly identify someone as dangerous

Type II: Fail to identify someone as dangerous

Two and three-strike laws

– Prevention or deserts?

Federal sentencing before 1984

Indeterminate sentences, actual length fixed by Parole

Commission after sentencing

Wide disparity in sentences given and served

Dishonest - persons usually served only 1/3 of their terms

Impetus for change

–

–

Honesty

Fairness

– Proportionality

Federal sentencing guidelines (1984)

Takes prevention and deserts into account

Abolished parole

Method

–

–

–

–

Sentencing table with 43 levels, probation to life imprisonment

Each crime has its own base level and its own range

Within crimes, certain characteristics (being armed, how much stolen) can increase the level

Other adjustments: role in the crime, accepting responsibility, criminal history

...and then it changed again – twice!

Blakely v. Washington (Supreme Court, no. 02-1632, 6/24/04)

–

–

Under the Sixth Amendment, any factors that are used to set a sentence above the standard range must be decided by the trier of fact

For example, if after a jury trial a judge uses the defendant’s past conduct to enhance his/her punishment, the jury must have determined, beyond a reasonable doubt, that this conduct took place.

U.S. v. Booker (Supreme Court, no. 04-104, 1/12/05)

–

Federal sentencing guidelines must be considered but are only “advisory”.

Under Sixth Amendment and other Federal statutes Courts need sufficient flexibility to make “reasonable” sentencing decisions.

– Factors to be considered include

seriousness of the offense promoting respect for the law

providing just punishment affording adequate deterrence protecting the public providing defendants with needed training and medical care