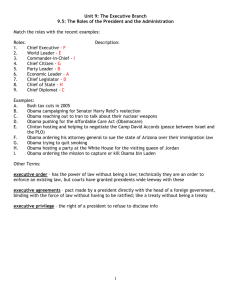

1NC - openCaselist 2012-2013

advertisement